Materialising Mutability in the Medium of Paint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ideological Analysis of the Birth of Chinese Indie Music

REPHRASING MAINSTREAM AND ALTERNATIVES: AN IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE BIRTH OF CHINESE INDIE MUSIC Menghan Liu A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2012 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kristen Rudisill Esther Clinton © 2012 MENGHAN LIU All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This thesis project focuses on the birth and dissemination of Chinese indie music. Who produces indie? What is the ideology behind it? How can they realize their idealistic goals? Who participates in the indie community? What are the relationships among mainstream popular music, rock music and indie music? In this thesis, I study the production, circulation, and reception of Chinese indie music, with special attention paid to class, aesthetics, and the influence of the internet and globalization. Borrowing Stuart Hall’s theory of encoding/decoding, I propose that Chinese indie music production encodes ideologies into music. Pierre Bourdieu has noted that an individual’s preference, namely, tastes, corresponds to the individual’s profession, his/her highest educational degree, and his/her father’s profession. Whether indie audiences are able to decode the ideology correctly and how they decode it can be analyzed through Bourdieu’s taste and distinction theory, especially because Chinese indie music fans tend to come from a community of very distinctive, 20-to-30-year-old petite-bourgeois city dwellers. Overall, the thesis aims to illustrate how indie exists in between the incompatible poles of mainstream Chinese popular music and Chinese rock music, rephrasing mainstream and alternatives by mixing them in itself. -

DISAPPEAR HERE Violence After Generation X

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · DISAPPEAR HERE Violence after Generation X Naomi Mandel THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS / COLUMBUS All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Ohio State University Press, 2015. Batch 1. Copyright © 2015 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mandel, Naomi, 1969– author. Disappear here : violence after Generation X / Naomi Mandel. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1286-8 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Violence in literature. 2. Violence—United States—20th century. 3. Generation X— United States—20th century. I. Title. PN56.V53M36 2015 809'.933552—dc23 2015010172 Cover design by Janna Thompson-Chordas Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Sabon Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. Cover image: Young woman with knife behind foil. © Bernd Friedel/Westend61/Corbis. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Ohio State University Press, 2015. Batch 1. To Erik with love and x x x All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Ohio State University Press, 2015. Batch 1. All Rights Reserved. Copyright © The Ohio State University Press, 2015. Batch 1. contents · · · · · · · · · List of Illustrations vi Acknowledgments vii introduction The Middle Children of History 1 one Why X Now? Crossing Out and Marking the Spot 9 two Nevermind: An X Critique of Violence 41 three The Game That Moves: Bret Easton Ellis, 1985–2010 79 four Something Empty in the Sky: 9/11 after X 111 five Not Yes or No: Fact, Fiction, Fidelity in Jonathan Safran Foer 150 six I Am Jack’s Revolution: Fight Club, Hacking, Violence after X 178 conclusion X Out 210 Works Cited 227 Index 243 All Rights Reserved. -

CS5 WEL Ruhlman Program13

Conference Schedule 8:30–9:30am Continental breakfast served in Pendleton Atrium and Science Center Focus. Continental Breakfast 9:30-10:40am Chinese Today: Near and Afar (panel discussion) Founders Hall 126 Humanities Sophia S. Chen, Wendy M. Foo, Virginia Hung, Kelsey A. Ridge, Christianne L.Wolfsen, Audrey M. Wozniak, Ji Qing Wu Controversial Public Art and Its Politics (panel discussion) Jewett Arts Center 450 Katherine E. Dresdner, Caitlin J. Greenhill, Diana T. Huynh, Laura C. Marin, Cassandra Tavolarella Science & Technology Breaking Bad: Drugs, Delivery, and Disease (short talks) Pendleton Hall East 139 Two Methods of Synthesizing Novel Thiocarbonyl Agents for Drug-Resistant Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Alexa Jackson, Amelia S. Williams The Synthesis and Evaluation of Residues 6-36 of Alpha-Synuclein Madelyn P. Kallman Tackling a Silent Disease: Determining Best Practices for Management of Childhood Stroke Hayley E. Malkin Progress Towards the Synthesis of a Novel Electroactive Compound for Surface Modification of Gold Nanoparticles Nicole A. Spiegelman, Hong Zhang High Impact Science on the Final Frontier (short talks) Science Center 104 Simple Impact Crater Morphometry: Distribution and Analysis of Martian Craters Lynn M. Geiger Circular Polarization and Incident Wavelength Independence in the Fresnel Rhomb Wanyi Li, Renee Lu Optimizing Exoplanet Transit Observations and Analysis Kirsten N. Blancato, Anna V. Payne Re-defining the Birdbrain: Investigations of Learning and Memory in Songbirds (panel discussion) Founders Hall 120 Andrea J. Bae, Napim Chirathivat, Houda G. Khaled, Sima Lotfi, Ana K. Ortiz, Milena Radoman, Sahitya C. Raja Sparkly Hats and Cookie Dough: Stories from Computer Security (panel discussion) Science Center 278 Erin Davis, Emily Erdman, Taili Feng, Michelle N. -

CAST BIOGRAPHIES PHIL JAMIESON As the Voice and Face Of

CAST BIOGRAPHIES PHIL JAMIESON As the voice and face of Grinspoon, Phil Jamieson fronted one of the most popular Australian bands of the last two decades. An accomplished singer, songwriter and guitarist, Jamieson’s generation-defining lyrics and vocal melodies first became etched into rock fans’ DNA in 1995, when the Lismore-born quartet rode a new wave of alternative music to become the first act Unearthed by national youth radio station triple j with its debut single - Sickfest. So began a love affair that maintained its heat and passion for over one thousand live shows, six consecutive Top 10 debuts and multi-platinum album sales. That initial romance with triple j’s listeners blossomed into full-bloom infatuation: an incredible 17 Grinspoon songs have polled in Hottest 100 countdowns over the years, led by the much-loved Chemical Heart (#2 in 2002; #63 in 2013’s Hottest 100 of All Time). With the release of seventh album Black Rabbits came the news in late 2013 that Grinspoon were entering hibernation indefinitely, yet Phil Jamieson remained as focused and passionate about music as ever pursuing a solo career in the meantime. Earlier this year Grinspoon announced the celebration of 20 years since their first album Guide to Better Living, this saw them back on the road playing to adoring sold-out crowds across the country over 4 months. Outside of studios and music venues, Jamieson co-founded the Rock N Ride tour for headspace, the National Youth and Mental Health Foundation, in 2013. The initiative is aimed at engaging local communities to raise awareness about mental health issues faced by young people. -

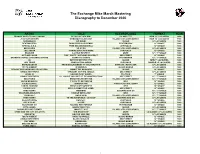

The Exchange Mike Marsh Mastering Discography to December 2020

The Exchange Mike Marsh Mastering Discography to December 2020 ARTIST TITLE RECORD LABEL FORMAT YEAR FRANKIE GOES TO HOLLYWOOD RELAX (12" SEX MIX) ISLAND / ZTT NEW 12" LACQUERS 1988 JOCEYLYN BROWN SOMEBODY ELSES GUY ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY NEW 12" LACQUERS 1988 SHRIEKBACK GO BANG! ISLAND LP LACQUERS 1988 BEATMASTERS BURN IT UP (ACID REMIX) RHYTHM KING 12" SINGLE 1988 SPECIAL A.K.A. FREE NELSON MANDELA CHRYSALIS 12" SINGLE 1988 MICA PARIS SO GOOD ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY LP LACQUERS 1988 JELLYBEAN COMING BACK FOR MORE CHRYSALIS 12" SINGLE 1988 ERASURE A LITTLE RESPECT MUTE 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 OUTLAW POSSE THE * PARTY / OUTLAWS IN EFFECT GEE STREET 12" SINGLE 1988 BRANDON COOKE & ROXANNE SHANTE SHARP AS A KNIFE PHONOGRAM 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 U2 WITH OR WITHOUT YOU ISLAND NEW 7" LACQUERS 1988 JUDI TZUKE COMPILATION ALBUM CHRYSALIS DOUBLE LP LACQUERS 1988 NAPALM DEATH FROM ENSLAVEMENT TO OBLITERATION EARACHE / REVOLVER LP LACQUERS 1988 TOOTS HIBBERT IN MEMPHIS ISLAND MANGO LP LACQUERS 1988 REGGAE PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA MINNIE THE MOOCHER ISLAND 12" SINGLE 1988 JUNGLE BROTHERS STRAIGHT OUT THE JUNGLE GEE STREET LP LACQUERS 1988 LEVEL 42 HEAVEN IN MY HANDS POLYDOR 7" SINGLE 1988 JUNGLE BROTHERS I'LL HOUSE YOU (GEE ST. RECONSTRUCTION) GEE STREET 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 MICA PARIS BREATHE LIFE INTO ME ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 BLOW MONKEYS IT PAYS TO BE TWELVE RCA 12" SINGLE 1988 STEVEN DANTE IMAGINATION CHRYSALIS COOLTEMPO 12" SINGLE 1988 TANITA TIKARAM TWIST IN MY SOBRIETY WEA 10" SINGLE 1988 RICHIE RICH MY D.J. (PUMP IT UP SOME) GEE STREET 12" SINGLE 1988 TODD TERRY WEEKEND SLEEPING BAG UK 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 TRAVELING WILBURYS HANDLE WITH CARE WEA 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 YOUNG M.C. -

Mike Marsh Discography

Mike Marsh Discography ARTIST TITLE RECORD LABEL FORMAT YEAR 02:54 SUGAR POLYDOR / FICTION DOWNLOAD SINGLE 2012 1789 CA IRA MON AMOUR UNIVERSAL MERCURY FRANCE CD SINGLE / DOWNLOAD 2011 0 8 0 0 1 VORAGINE WORKING PROGRESS CD ALBUM 2007 18 WHEELER THE HOURS AND THE TIMES CREATION CD SINGLE / 12" SINGLE 1996 18 WHEELER YEAR ZERO CREATION CD ALBUM / LP LACQUERS 1996 49ERS GOT TO BE FREE ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY CD SINGLE / 12" / 7" SINGLE 1992 4GOTTEN FLOOR THE FORGOTTEN FLOOR JATO MUSIC CD ALBUM 2008 808 STATE DON SOLARIS ZTT CD ALBUM / LP LACQUERS 1996 808 STATE BOND ZTT CD SINGLE / 12" / 10" SINGLE 1996 808 STATE LOPEZ ZTT CD SINGLE / 12" SINGLE 1996 AARON BIRDS IN THE STORM WAGRAM / CINQ 7 CD ALBUM / DOWNLOAD 2010 ABC GREATEST HITS PHONOGRAM CD PRE-MASTERING 1990 ADAM CLAYTON & LARRY MULLEN MISSION : IMPOSSIBLE MOTHER 7" SINGLE 1996 ADAM KESHER CHALLENGING NATURE DISQUE PRIMEUR CD ALBUM / DOWNLOAD 2010 ADD N TO (X) AVANT HARD MUTE CD ALBUM / LP LACQUERS 1998 ADD N TO (X) REVENGE OF THE BLACK REGENT MUTE CD SINGLE / 12" / 7" SINGLE 1999 ADD N TO (X) LOUD LIKE NATURE MUTE CD ALBUM / LP LACQUERS 2002 ADDIE BRIK LOVED HUNGRY BREAKIN' BEATS CD ALBUM 2003 ADDIE BRIK STRIKE THE TENT ADDIE BRIK CD ALBUM 2008 ADELE SET FIRE TO THE RAIN (THOMAS GOLD REMIX) XL RECORDINGS CD SINGLE / DOWNLOAD 2011 ADRENALIN JUNKIES ADRENALIN JUNKIES LA PLAGE CD ALBUM 2008 ADSTEDT DREAMING WIDE AWAKE VERATONE SWITZERLAND DOWNLOAD SINGLE 2012 AFTERGLOW NEVER GROW OLD EP JACK McDONALD DOWNLOAD SINGLE 2012 AGENT PROVOCATEUR RED TAPE EPIC CD SINGLE / 12" / 7" SINGLE 1996