World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

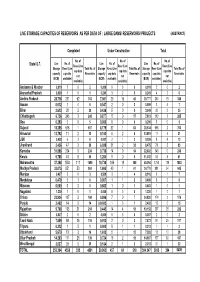

Live Storage Capacities of Reservoirs As Per Data of : Large Dams/ Reservoirs/ Projects (Abstract)

LIVE STORAGE CAPACITIES OF RESERVOIRS AS PER DATA OF : LARGE DAMS/ RESERVOIRS/ PROJECTS (ABSTRACT) Completed Under Construction Total No. of No. of No. of Live No. of Live No. of Live No. of State/ U.T. Resv (Live Resv (Live Resv (Live Storage Resv (Live Total No. of Storage Resv (Live Total No. of Storage Resv (Live Total No. of cap data cap data cap data capacity cap data Reservoirs capacity cap data Reservoirs capacity cap data Reservoirs not not not (BCM) available) (BCM) available) (BCM) available) available) available) available) Andaman & Nicobar 0.019 20 2 0.000 00 0 0.019 20 2 Arunachal Pradesh 0.000 10 1 0.241 32 5 0.241 42 6 Andhra Pradesh 28.716 251 62 313 7.061 29 16 45 35.777 280 78 358 Assam 0.012 14 5 0.547 20 2 0.559 34 7 Bihar 2.613 28 2 30 0.436 50 5 3.049 33 2 35 Chhattisgarh 6.736 245 3 248 0.877 17 0 17 7.613 262 3 265 Goa 0.290 50 5 0.000 00 0 0.290 50 5 Gujarat 18.355 616 1 617 8.179 82 1 83 26.534 698 2 700 Himachal 13.792 11 2 13 0.100 62 8 13.891 17 4 21 J&K 0.028 63 9 0.001 21 3 0.029 84 12 Jharkhand 2.436 47 3 50 6.039 31 2 33 8.475 78 5 83 Karnatka 31.896 234 0 234 0.736 14 0 14 32.632 248 0 248 Kerala 9.768 48 8 56 1.264 50 5 11.032 53 8 61 Maharashtra 37.358 1584 111 1695 10.736 169 19 188 48.094 1753 130 1883 Madhya Pradesh 33.075 851 53 904 1.695 40 1 41 34.770 891 54 945 Manipur 0.407 30 3 8.509 31 4 8.916 61 7 Meghalaya 0.479 51 6 0.007 11 2 0.486 62 8 Mizoram 0.000 00 0 0.663 10 1 0.663 10 1 Nagaland 1.220 10 1 0.000 00 0 1.220 10 1 Orissa 23.934 167 2 169 0.896 70 7 24.830 174 2 176 Punjab 2.402 14 -

“Demographic Characteristics of Satara District”

“DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF SATARA DISTRICT” A Dissertation Submitted To The TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPITH GULTEKDI, PUNE for the Degree Of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY IN GEOGRAPHY UNDER THE FACULTY OF MORAL AND SOCIAL SCIENCE By Mr. GODASE JITENDRA MANSING (M. A.) Under The Guidance Of Dr. ZODAGE S. B. (M. A., B. Ed., Ph.D.) ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY, CHH. SHIVAJI COLLEGE, SATARA MARCH 2011 1 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation entitled “DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF SATARA DISTRICT” Which is being submitted herewith for the award of the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Geography of TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE is the result of original research work completed by Mr. JITENDRA MANSING GODASE under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the work embodied in this thesis has not formed earlier the basis for the award of any degree of similar title of this or any other University or Examining body. PLACE: SATARA Dr. ZODAGE S. B. DATE: /03/2011 RESEARCH GUIDE 2 DECLARATION I hereby declared that the thesis entitled “DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF SATARA DISTRICT” Which is being submitted to TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy in Geography under the supervision and guidance of Dr. Zodage S.B. is my original research work and the conclusion drawn therein are based on the data and information collected myself. To the best of my knowledge and belief, this work has not formed the basis for the award of my degree of similar title of this or any other University or examining body. -

Integrated State Water Plan for Lower Bhima Sub Basin (K-6) of Krishna Basin

Maharashtra Krishna Valley Development Corporation Pune. Chief Engineer (S.P) W.R.D Pune. Integrated state water Plan for Lower Bhima Sub basin (K-6) of Krishna Basin Osmanabad Irrigation Circle, Osmanabad K6 Lower Bhima Index INDEX CHAPTER PAGE NO. NAME OF CHAPTER NO. 1.0 INTRODUCTION 0 1.1 Need and principles of integrated state water plan. 1 1.2 Objectives of a state water plan for a basin. 1 1.3 Objectives of the maharashtra state water policy. 1 1.4 State water plan. 1 1.5 Details of Catchment area of Krishna basin. 2 1.6 krishna basin in maharashtra 2 1.7 Location of lower Bhima sub basin (K-6). 2 1.8 Rainfall variation in lower Bhima sub basin. 2 1.9 Catchment area of sub basin. 3 1.10 District wise area of lower Bhima sub basin. 3 1.11 Topographical descriptions. 5 1.11 Flora and Fauna in the sub basin. 6 2.0 RIVER SYSTEM 2.1 Introduction 11 2.2 Status of Rivers & Tributaries. 11 2.3 Topographical Description. 11 2.4 Status of Prominent Features. 12 2.5 Geomorphology. 12 2.6 A flow chart showing the major tributaries in the sub basin. 13 3.0 GEOLOGY AND SOILS 3.1 Geology. 16 3.1.1 Introduction. 16 3.1.2 Drainage. 16 3.1.3 Geology. 16 3.1.4 Details of geological formation. 17 K6 Lower Bhima Index 3.2 Soils 18 3.2.1 Introduction. 18 3.2.2 Land capability Classification of Lower Bhima Sub Basin (K6). -

GIPE-175649-10.Pdf

1: '*"'" GOVERNMENT OF MAIIAitASJRllA OUTLINE· OF · ACTIVITIES For 1977-78 and 1978-79 IRRIGATION DEPARTMENT OUTLINE OF ACTIVITIES 1977-78 AND 1978-79 IRRIGATION DEPARTMENT CONTENTS CHAl'TI!R PAGtiS I. Introduction II. Details of Major and Medium Irrigation Projects 6 Ul. Minor Irrigation Works (State sector) and Lift Irrigation 21 IV. Steps taken to accelerate the pace of Irrigation Development 23 V. Training programme for various Technical and Non-Technical co~ 36 VI. Irrigation Management, Flood Control and ElCiension and Improvement 38 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION I.· The earstwhile Public Works Department was continued uuaffect~u after Independence in 1947, but on formation of the State ot Maharashtra in 1_960, was divided into two Departments. viz. .(1) Buildings and Communica· ticns Dep4rtment (now named · as ·'Public Works ' and Housing Department) and (ii) Irrigation and Power Department, as it became evident that the Irrigation programme to be t;~ken up would ·need a separate Depart· ment The activities in . both the above Departments have considerably increased since then and have nei:eSllitated expansion of both the Depart ments. Further due t~ increased ·activities of the Irrigation and Power Department the subject <of Power (Hydro only) has since been allotted to Industries,"Energy and· Labour Department. Public Health Engineering wing is transferred to Urban. Development and Public Health Department. ,t2.. The activities o(the Irrigation ·Department can be divided broadly into the following categories :- (i) Major and Medium Irrigation Projects. (u) Minor Irrigation Projects (State Sector). (ii1) Irrigation Management. (iv) Flood Control. tv) Research. .Designs and Training. (vi) Command Area Development. (vii) Lift Irrigation Sc. -

Understanding the Alignment of the Open and Close Conduit, Maharashtra

NOVATEUR PUBLICATIONS International Journal of Research Publications in Engineering and Technology [IJRPET] ISSN: 2454-7875 VOLUME 3, ISSUE 10, Oct. -2017 LINKING OF DHOM RESERVOIR TO NER RESERVOIR: UNDERSTANDING THE ALIGNMENT OF THE OPEN AND CLOSE CONDUIT, MAHARASHTRA. S. G. MUNDE Research Scholar, Department of Civil Engineering, Sinhgad College of Engineering, Pune. D. R. VAIDYA Assistant Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, Sinhgad College of Engineering, Pune. S. S. NIKAM Assistant Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, Sou Venutai Polytechnic, Sinhgad Institute, Pune. N. J. SATHE Associate Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, Universal College of Engineering & Research, Pune. [email protected] ABSTRACT: KEYWORDS: Interlinking, Canal, Electrical Resistivity, Water forms the life line in human life. Increase in etc. population leads to the increase in requirement of water. There are various places in Maharashtra where I. INTRODUCTION: water scarcity is being observed and few places where Food, clothing and shelter are basic need of human surplus water is available. Inter linking of water being. In addition, water is the most essential to stay alive bodies deals with the transfer of water from surplus for human being. Water availability varies from place to region to the deficient region. place. This dissimilarity depends on rainfall intensity at The present study specifically deals with transfer of that place. Abundant water is available in Himalayan water from Dhom dam near Mahabaleshwar, which region of India, as per National Water Development comes under heavy rainfall region in Maharashtra Authority (NWDA). state and another area is Ner reservoir in Satara There are various places in Maharashtra where water district. -

FM Holds Inter-Ministerial Meeting on Banning Sugar Futures Sugarcane

NEWS FLASH –24th August, 2016 SUGAR FM holds inter-ministerial meeting on banning sugar futures Finance Minister Arun Jaitley on Monday held an inter-ministerial consultation on imposing ban on sugar futures trading in an effort to curb speculation and check price rise of the sweetener during festival season. MoS for Food C L Chaudhary, secretaries from Food, Consumer Affairs, Agriculture and finance ministries were present in the meeting. The meeting comes in the backdrop of the Food and Consumer Affairs Ministry recommending the regulator Sebi to ban sugar futures trade to check prices. Sugar prices in the retail markets have risen in last few weeks and are ruling at Rs 42 per kg in the national capital. “We discussed about banning sugar futures trading in the meeting called by the FM. It was an initial discussion and nothing was decided,” Chaudhary told Press Trust of India after the meeting. Food Secretary Vrinda Sarup echoed the same and said: “Nothing has been finalised on banning sugar futures.” Sugar is largely traded on leading agri-commodity bourse National Commodity and Derivatives Exchange (NCDEX). The exchange has already raised the margin amount to be deposited by both sellers and buyers on its platform. To check prices, the government recently imposed an export duty of 20 per cent on sugar as part of its efforts to curb outbound shipments and boost domestic supply. India’s sugar production is estimated to decline to 25 million tonnes in the 2015-16 season (October-September) from 28.3 million tonnes in the previous year. The outlook for the next year is not encouraging as sugar production is pegged lower at 23.26 million tonnes. -

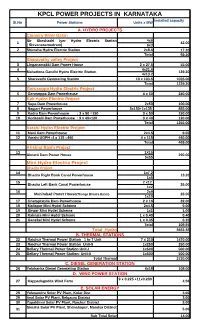

KPCL POWER PROJECTS in KARNATAKA Installed Capacity Sl.No Power Stations Units X MW

KPCL POWER PROJECTS IN KARNATAKA Installed capacity Sl.No Power Stations Units x MW A. HYDRO PROJECTS Cauvery River Basin Sir Sheshadri Iyer Hydro Electric Station 4x6 1 42.00 ( Shivanasamudram) 6x3 2 Shimsha Hydro Electric Station 2x8.6 17.20 Total 59.20 Sharavathy valley Project 3 Linganamakki Dam Power House 2 x 27.5 55.00 4 4x21.6 Mahathma Gandhi Hydro Electric Station 139.20 4x13.2 5 Sharavathi Generating Station 10 x 103.5 1035.00 Total 1229.20 Gerusoppa Hydro Electric Project 6 Gerusoppa Dam Powerhouse 4 x 60 240.00 Kali Hydro Electric Project 7 Supa Dam Powerhouse 2x50 100.00 8 Nagjari Powerhouse 5x150+1x135 885.00 9 Kadra Dam Powerhouse : 3 x 50 =150 3 x 50 150.00 10 Kodasalli Dam Powerhouse : 3 x 40=120 3 x 40 120.00 Total 1255.00 Varahi Hydro Electric Project 11 Mani Dam Powerhouse 2x4.5 9.00 12 Varahi UGPH :4 x 115 =460 4 x 115 460.00 Total 469.00 Krishna Basin Project 13 1X15 Almatti Dam Power House 290.00 5x55 Mini Hydro Electric Project Bhadra Project 14 1x7.2 Bhadra Right Bank Canal Powerhouse 13.20 1x6 15 2 x12 Bhadra Left Bank Canal Powerhouse 26.00 1x2 16 2x9 Munirabad Power House(Thunga Bhadra Basin) 28.00 1x10 17 Ghataprabha Dam Powerhouse 2 x 16 32.00 18 Mallapur Mini Hydel Scheme 2x4.5 9.00 19 Sirwar Mini Hydel Scheme 1x1 1.00 20 Kalmala Mini Hydel Scheme 1 x 0.40 0.40 21 Ganekal Mini Hydel Scheme 1 x 0.35 0.35 Total 109.95 Total Hydro 3652.35 B. -

6. Water Quality ------61 6.1 Surface Water Quality Observations ------61 6.2 Ground Water Quality Observations ------62 7

Version 2.0 Krishna Basin Preface Optimal management of water resources is the necessity of time in the wake of development and growing need of population of India. The National Water Policy of India (2002) recognizes that development and management of water resources need to be governed by national perspectives in order to develop and conserve the scarce water resources in an integrated and environmentally sound basis. The policy emphasizes the need for effective management of water resources by intensifying research efforts in use of remote sensing technology and developing an information system. In this reference a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed on December 3, 2008 between the Central Water Commission (CWC) and National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC), Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) to execute the project “Generation of Database and Implementation of Web enabled Water resources Information System in the Country” short named as India-WRIS WebGIS. India-WRIS WebGIS has been developed and is in public domain since December 2010 (www.india- wris.nrsc.gov.in). It provides a ‘Single Window solution’ for all water resources data and information in a standardized national GIS framework and allow users to search, access, visualize, understand and analyze comprehensive and contextual water resources data and information for planning, development and Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM). Basin is recognized as the ideal and practical unit of water resources management because it allows the holistic understanding of upstream-downstream hydrological interactions and solutions for management for all competing sectors of water demand. The practice of basin planning has developed due to the changing demands on river systems and the changing conditions of rivers by human interventions. -

Why Do Interstate Water Disputes Emerge and Recur? an Anatomy of Ambiguities, Antagonisms and Asymmetries

Pre-publication Draft Why do interstate water disputes emerge and recur? an anatomy of ambiguities, antagonisms and asymmetries Srinivas Chokkakula Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi [email protected] (To be published under RULNR monograph series, CESS, Hyderabad) Srinivas Chokkakula Pre-publication Draft Acknowledgements This monograph has taken much longer than initially planned. The research presented here is part of my dissertation work, and I have planned to publish this soon after submitting the dissertation (for my Ph D from the University of Washington, Seattle, USA) in 2015. The earlier draft received some useful and critical inputs, which set me on revising it substantially and also increasing its scope. It is now considerably improved and I hope that it will be received with interest. I express my deep gratitude to two individuals on this account: Dr Radha D’Souza for her critical review and discussion of the draft, and Dr Gopinath Reddy at CESS for his extraordinary patience and undeserving belief in me and my work. I am also thank Prof Gopal Kadekodi for his comments on an earlier version of the draft. I thank my colleagues at the Centre for Policy Research (CPR), New Delhi, for conversations, inputs and support at different stages of producing this research. I am grateful to Dr Pratap Bhanu Mehta and Dr Partha Mukhopadhyay for their unstinting support. I have been fortunate to benefit from generous conversations with late Prof Ramaswamy Iyer on the subject. I have also benefitted from interactions with several professional colleagues engaged directly with interstate water disputes resolution. I want to particularly acknowledge the enthusiastic the generous support of Mr Mohan Katarki. -

District Survey Report 2020-2021

District Survey Report Satara District DISTRICT MINING OFFICER, SATARA Prepared in compliance with 1. MoEF & CC, G.O.I notification S.O. 141(E) dated 15.1.2016. 2. Sustainable Sand Mining Guidelines 2016. 3. MoEF & CC, G.O.I notification S.O. 3611(E) dated 25.07.2018. 4. Enforcement and Monitoring Guidelines for Sand Mining 2020. 1 | P a g e Contents Part I: District Survey Report for Sand Mining or River Bed Mining ............................................................. 7 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 7 3. The list of Mining lease in District with location, area, and period of validity ................................... 10 4. Details of Royalty or Revenue received in Last five Years from Sand Scooping Activity ................... 14 5. Details of Production of Sand in last five years ................................................................................... 15 6. Process of Deposition of Sediments in the rivers of the District ........................................................ 15 7. General Profile of the District .............................................................................................................. 25 8. Land utilization pattern in district ........................................................................................................ 27 9. Physiography of the District ................................................................................................................ -

Answered On:21.08.2000 Clearance to Projects in Karnataka Rudragouda Patil

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ENVIRONMENT AND FORESTS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:4352 ANSWERED ON:21.08.2000 CLEARANCE TO PROJECTS IN KARNATAKA RUDRAGOUDA PATIL Will the Minister of ENVIRONMENT AND FORESTS be pleased to state: (a) the number and details of the various projects sent to the Union Government by Karnataka for environmental clearance during the last three years; (b) whether Upper Krishna Project, Stage-I and II and Uduthorehalla Project have been given environmental clearance; and (c) if not, the reasons therefor and the time by which environmental clearance is likely to be accorded by the Union Government? Answer MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND FORESTS (SHRI BABU LAL MARANDI) (a) 25 projects were received during last three years from Karnataka for environmental clearance . A list is annexed. (b)&(c) Upper Krishna project Stage-I consists of Phase-I , Phase-II and Phase-IIIP. hase I was not referred to this Ministry for environmental clearance, Phase-II & Phase-III were accorded environmental clearance on 05.04.1989 and 18.07.2000 respectively. Stage-II project was considered by the Expert Committee for River Valley & Hydroelectric projects on 21.07.2000 for environmental clearance. Additional information sought from the project proponent has not been received. Decision on the proposal for environmental clearance will be taken within ninety(90) days of receipt of complete information. Uduthorehalla project has not been received for environmental clearance. ANNEXUREI N RESPECT OF PART(a)OF LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.4352 FOR 21.08.2000 REGARDING `CLEARANCE TO PROJECTS IN KARNATAKA `. S.No. -

Biodiversity of Kanher Dam of Satara District MS, India Sandhya M

Research Journal of Recent Sciences _________________________________________________ ISSN 2277-2502 Vol. 4(ISC-2014), 87-92 (2015) Res. J. Recent. Sci. Biodiversity of Kanher dam of Satara district MS, India Sandhya M. Pawar Department of Zoology, Padmabhushan Dr. Vasantraodada Patil Mahavidyalaya, Tasgaon, Dist. Sangli, INDIA Available online at: www.isca.in, www.isca.me Received 15 th November 2014, revised 24 th January 2015, accepted 2nd February 2015 Abstract River Venna is a tributary of Krishna river and has its orgin in nearMahabaleshwar. It runs a distance 45 km before meets with river Krishna near Satara on which Kanher dam was constructed.The water from the dam is utilised for irrigation, generation of electricity, drinking, aquaculture practices and recreation purposes. The present study comparies with limnological parameters, plankton diversity and survey of migratory and resident bird species. The plankton and bird species are best biological parameters of water and enviromental quality and assecement of conservation value of any habitat.The complied data needss to be further strengthened for improving strategies that insure stability and sustainability of study area. Keywords: Biodiversity, Kanher dam, Satara district. Introduction 10 litre capacity from the two sites of each reservoir. The water sampling was carried out between 9.00 am to 12.00 Water has unique property of dissolving and carrying noon every month and brought to the laboratory. The water suspension, a huge variety of chemicals has undesirable samples were analyzed for various physico-chemical consequence that water can easily become contaminated. parameters such as temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, Water is the most important natural resource for the survival carbon dioxide, total hardness, total dissolved solids, of human as well as plants.