Jack Kerouac's Path to Enlightenment In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Importance of Mobilty in Jack Kerouac's on the Road And

SOBİAD Mart 2015 Onur KAYA IMPORTANCE OF MOBILTY IN JACK KEROUAC’S ON THE ROAD AND DENNIS HOPPER’S EASY RIDER Arş. Gör. Onur KAYA Abstract Journey as a mobility in 1950s and 1960s of the United States of America showed itself in the works of authors and directors of the films. Among them, Jack Kerouack’s On The Road (1955) and Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969) are significant works. Analysing both works will put forth representation of mobility in America and the period. For the method, mobility notion will be emphasized. The mobility notion in works and representation of its effects on people, period will be analyzed. Comparison of representation of mobility in two works will be done. Finally, the study will reveal the importance of mobility in the American society. Key Words: Beats, 50s, 60s, Mobility, Road JACK KEROUAC’IN ON THE ROAD VE DENNIS HOPPER’IN EASY RIDER YAPITLARINDA HAREKETLİLİĞİN ÖNEMİ Öz Yolculuk bir hareketlilik olarak Amerika Birleşik Devletlerinin 1950ler ve 1960larında yazarlarla film yönetmenlerinin eserlerinde kendisini göstermiştir. Bunlar içerisinde Jack Kerouack’ın On The Road (1955) ve Dennis Hopper’ın Easy Rider (1969) eserleri önemli yapıtlardır. Her iki eserin incelenmesi o dönemde ve Amerika’da hareketliliğin temsilini ortaya koyacaktır. Metot olarak hareketlilik kavramı irdelenecektir. Eserlerdeki hareketlilik kavramı ve onun insanlarla dönem üzerindeki etkileri analiz edilecektir. Her iki eserdeki hareketlililiğin temsilinin karşılaştırılması yapılacaktır. Sonuç olarak çalışma Amerikan toplumundaki hareketliliğin -

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (Guest Post)*

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (guest post)* Allen Ginsberg, c. 1959 The Poem That Changed America It is hard nowadays to imagine a poem having the sort of impact that Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” had after its publication in 1956. It was a seismic event on the landscape of Western culture, shaping the counterculture and influencing artists for generations to come. Even now, more than 60 years later, its opening line is perhaps the most recognizable in American literature: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness…” Certainly, in the 20h century, only T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” can rival Ginsberg’s masterpiece in terms of literary significance, and even then, it is less frequently imitated. If imitation is the highest form of flattery, then Allen Ginsberg must be the most revered writer since Hemingway. He was certainly the most recognizable poet on the planet until his death in 1997. His bushy black beard and shining bald head were frequently seen at protests, on posters, in newspapers, and on television, as he told anyone who would listen his views on poetry and politics. Alongside Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel, “On the Road,” “Howl” helped launch the Beat Generation into the public consciousness. It was the first major post-WWII cultural movement in the United States and it later spawned the hippies of the 1960s, and influenced everyone from Bob Dylan to John Lennon. Later, Ginsberg and his Beat friends remained an influence on the punk and grunge movements, along with most other musical genres. -

The 1957 Howl Obscenity Trial and Sexual Liberation

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2015 Apr 28th, 1:00 PM - 2:15 PM A Howl of Free Expression: the 1957 Howl Obscenity Trial and Sexual Liberation Jamie L. Rehlaender Lakeridge High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Cultural History Commons, Legal Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Rehlaender, Jamie L., "A Howl of Free Expression: the 1957 Howl Obscenity Trial and Sexual Liberation" (2015). Young Historians Conference. 1. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2015/oralpres/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. A HOWL OF FREE EXPRESSION: THE 1957 HOWL OBSCENITY TRIAL AND SEXUAL LIBERATION Jamie L. Rehlaender Dr. Karen Hoppes HST 201: History of the US Portland State University March 19, 2015 2 A HOWL OF FREE EXPRESSION: THE 1957 HOWL OBSCENITY TRIAL AND SEXUAL LIBERATION Allen Ginsberg’s first recitation of his poem Howl , on October 13, 1955, at the Six Gallery in San Francisco, ended in tears, both from himself and from members of the audience. “The people gasped and laughed and swayed,” One Six Gallery gatherer explained, “they were psychologically had, it was an orgiastic occasion.”1 Ironically, Ginsberg, upon initially writing Howl , had not intended for it to be a publicly shared piece, due in part to its sexual explicitness and personal references. -

The Impact of Allen Ginsberg's Howl on American Counterculture

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Croatian Digital Thesis Repository UNIVERSITY OF RIJEKA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Vlatka Makovec The Impact of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl on American Counterculture Representatives: Bob Dylan and Patti Smith Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the M.A.in English Language and Literature and Italian language and literature at the University of Rijeka Supervisor: Sintija Čuljat, PhD Co-supervisor: Carlo Martinez, PhD Rijeka, July 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis sets out to explore the influence exerted by Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl on the poetics of Bob Dylan and Patti Smith. In particular, it will elaborate how some elements of Howl, be it the form or the theme, can be found in lyrics of Bob Dylan’s and Patti Smith’s songs. Along with Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and William Seward Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, Ginsberg’s poem is considered as one of the seminal texts of the Beat generation. Their works exemplify the same traits, such as the rejection of the standard narrative values and materialism, explicit descriptions of the human condition, the pursuit of happiness and peace through the use of drugs, sexual liberation and the study of Eastern religions. All the aforementioned works were clearly ahead of their time which got them labeled as inappropriate. Moreover, after their publications, Naked Lunch and Howl had to stand trials because they were deemed obscene. Like most of the works written by the beat writers, with its descriptions Howl was pushing the boundaries of freedom of expression and paved the path to its successors who continued to explore the themes elaborated in Howl. -

Kerouac's Music of Sublimity in Tristessa

A Song of Beauty and Death: Kerouac’s Music of Sublimity in Tristessa Tanguy Harma PhD candidate Goldsmiths, University of London Tristessa was written between 1955 and 1956, as Kerouac paid a visit to William Burroughs in Mexico City.1 It is a story of unrequited love between Jack Duluoz, and a young Mexican woman named Tristessa, who is using and abusing morphine as she spirals into addiction. The story is grounded in the narrator’s attraction to Tristessa’s beauty and self-destruction – a beauty generated by self- destruction from the perspective of Duluoz. Kerouac celebrates his heroine as much for her beauty as for her self-destructive tendencies. In fact, it seems that Tristessa is death in disguise: through a rhetorical process of personification, Kerouac gives a physical form to his obsession with death, by making it beautiful and enticing; in one word, desirable. Tristessa embodies a remarkable oxymoron that intermingles beauty with death, joy with fright and redemption with threat, thereby suggesting a modality that partakes in the sublime. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), through works such as Critique of Judgement (1790), and Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and the Sublime (1799), investigated our capacity to form aesthetic judgement on 1 Jack Kerouac, Tristessa [1960] (New York: Penguin books, 1992). 1 phenomena around us.2 For Kant, the sublime is distinct from the beautiful.3 The beautiful is an object of contemplation that provides pleasure through its mere form. The sublime, on the other hand, involves a kind of beauty that generates a breach in rational understanding, and that stems from the amplitude and indecipherability of the phenomenon at stake: ‘In the immeasurableness of nature and the incompetence of our faculty for adopting a standard proportionate to the aesthetic estimation of the magnitude of its realm, we found our own limitation’.4 For Kant, the sublime is a fearful process, because at first, man’s imagination cannot comprehend the phenomenon. -

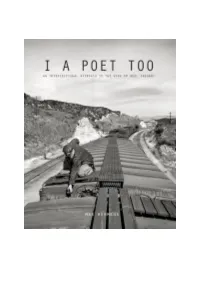

An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady

“I a poet too”: An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady “Look, my boy, see how I write on several confused levels at once, so do I think, so do I live, so what, so let me act out my part at the same time I’m straightening it out.” Max Hermens (4046242) Radboud University Nijmegen 17-11-2016 Supervisor: Dr Mathilde Roza Second Reader: Prof Dr Frank Mehring Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter I: Thinking Along the Same Lines: Intersectional Theory and the Cassady Figure 10 Marginalization in Beat Writing: An Emblematic Example 10 “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit”: Towards a Theoretical Framework 13 Intersectionality, Identity, and the “Other” 16 The Critical Reception of the Cassady Figure 21 “No Profane History”: Envisioning Dean Moriarty 23 Critiques of On the Road and the Dean Moriarty Figure 27 Chapter II: Words Are Not For Me: Class, Language, Writing, and the Body 30 How Matter Comes to Matter: Pragmatic Struggles Determine Poetics 30 “Neal Lived, Jack Wrote”: Language and its Discontents 32 Developing the Oral Prose Style 36 Authorship and Class Fluctuations 38 Chapter III: Bodily Poetics: Class, Gender, Capitalism, and the Body 42 A poetics of Speed, Mobility, and Self-Control 42 Consumer Capitalism and Exclusion 45 Gender and Confinement 48 Commodification and Social Exclusion 52 Chapter IV: Writing Home: The Vocabulary of Home, Family, and (Homo)sexuality 55 Conceptions of Home 55 Intimacy and the Lack 57 “By their fruits ye shall know them” 59 1 Conclusion 64 Assemblage versus Intersectionality, Assemblage and Intersectionality 66 Suggestions for Future Research 67 Final Remarks 68 Bibliography 70 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank Mathilde Roza for her assistance with writing this thesis. -

Kerouac's Dharma Bums (1958) & Delillo's Americana (1971): an Investigation of the Influences of Media, Spatiality

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 5-10-2014 Kerouac's Dharma Bums (1958) & DeLillo's Americana (1971): An Investigation of the Influences of Media, Spatiality, & Buddhism on Selfhood in Mid-twentieth-century American Culture & Consciousness Alex Ryan Gregor Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Recommended Citation Gregor, Alex Ryan, "Kerouac's Dharma Bums (1958) & DeLillo's Americana (1971): An Investigation of the Influences of Media, Spatiality, & Buddhism on Selfhood in Mid-twentieth-century American Culture & Consciousness." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/163 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KEROUAC‟S DHARMA BUMS (1958) & DELILLO‟S AMERICANA (1971): AN INVESTIGATION OF THE INFLUENCES OF MEDIA, SPATIALITY, & BUDDHISM ON SELFHOOD IN MID-TWENTIETH-CENTURY AMERICAN CULTURE & CONSCIOUSNESS by ALEX RYAN GREGOR Under the Direction of Dr. Christopher Kocela ABSTRACT In Dharma Bums (1958), by Jack Kerouac, and Americana (1971), by Don DeLillo, the authors explore the complexity of selfhood as pertaining to individual identity and subjectivity in mid-twentieth century American culture and consciousness, paying specific attention to the relation that these concepts have with media, spatiality, and Buddhism. Although numerous critics provide extensive analyses of these texts, authors, and themes, no critic has paired these texts and authors, and investigated these particular themes in relation to selfhood. -

Beat Generation Icon William S. Burroughs Found Love – and Loved Life – During His Years in Lawrence

FOR BURROUGHS, IT ALL ADDED UP BURROUGHS CREEK TRAIL & LINEAR PARK Beat Generation icon William S. Burroughs found love – and loved life – during his years in Lawrence William S. Burroughs, once hailed by In 1943, Burroughs met Allen Ginsberg America after charges of obscenity were 11th Street Norman Mailer as “the only American and Jack Kerouac. They became fast rejected by the courts. In the meantime, novelist living today who may conceivably friends, forming the nucleus of the Burroughs had moved to Paris in 1958, be possessed by genius,” lived in Lawrence nascent Beat Generation, a group of working with artist Brion Gysin, then on a few blocks west of this spot for the last 16 often experimental writers exploring to London in 1960, where he lived for 14 13th Street years of his life. Generally regarded as one postwar American culture. years, publishing six novels. of the most influential writers of the 20th century, his books have been translated Burroughs became addicted to narcotics In 1974, Burroughs returned to 15th Street into more than 70 languages. Burroughs in 1945. The following year, he New York City where he met James was also one of the earliest American married Joan Vollmer, the roommate Grauerholz, a former University of multimedia artists; his films, recordings, of Kerouac’s girlfriend. They moved Kansas student from Coffeyville, paintings and collaborations continue to to a farm in Texas, where their son Kansas, who soon became Burroughs’ venue venue A A inspire artists around the world. He is the Billy was born. In 1948, they relocated secretary and manager. -

The Importance of Neal Cassady in the Work of Jack Kerouac

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Spring 2016 The Need For Neal: The Importance Of Neal Cassady In The Work Of Jack Kerouac Sydney Anders Ingram As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Ingram, Sydney Anders, "The Need For Neal: The Importance Of Neal Cassady In The Work Of Jack Kerouac" (2016). MSU Graduate Theses. 2368. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/2368 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEED FOR NEAL: THE IMPORTANCE OF NEAL CASSADY IN THE WORK OF JACK KEROUAC A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, English By Sydney Ingram May 2016 Copyright 2016 by Sydney Anders Ingram ii THE NEED FOR NEAL: THE IMPORTANCE OF NEAL CASSADY IN THE WORK OF JACK KEROUAC English Missouri State University, May 2016 Master of Arts Sydney Ingram ABSTRACT Neal Cassady has not been given enough credit for his role in the Beat Generation. -

Dostoevsky and the Beat Generation

MARIA BLOSHTEYN Dostoevsky and the Beat Generation American literary history is rich with heroes of counterculture, maverick writers and poets who were rejected by the bulk of their contemporaries but inspired a cult-like following among a few devotees. The phenomenon of Beat Generation writers and poets, however, is unique in twentieth-century American letters precisely because they managed to go from marginal underground classics of the 1950s to the official voice of dissent and cultural opposition of the 1960s, a force to be reckoned with. Their books were adopted by hippies and flower children, their poems chanted at sit-ins, their lives faithfully imitated by a whole generation of young baby boomers. Their antiauthoritarian ethos along with their belief in the brotherhood of mankind were the starting point of a whole movement that gave the United States such social and cultural watersheds as Woodstock and the Summer of Love, the Chicago Riots and the Marches on Washington. The suggestion that Dostoevsky had anything to do with the American Sexual Revolution of the 1960s and street rioting in American urban centres might seem at first to be far-fetched. It is, however, a powerful testimony to Dostoevsky’s profound impact on twentieth-century American literature and culture that the first Beats saw themselves as followers of Dostoevsky and established their personal and literary union (and, as it were, the entire Beat movement) on the foundation of their shared belief in the primacy of Dostoevsky and his novels. Evidence of Dostoevsky’s impact on such key writers and poets of the Beat Generation as Allen Ginsberg (1926-1997), Jack Kerouac (1922-1969), and William Burroughs (1914-1997) is found in an almost embarrassing profusion: scattered throughout their essays, related in their correspondence, broadly hinted at and sometimes explicitly indicated in their novels and poems. -

Gregory Corso - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Gregory Corso - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Gregory Corso(26 March 1930 – 17 January 2001) Gregory Nunzio Corso was an American poet, youngest of the inner circle of Beat Generation writers (with <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/jack- kerouac/">Jack Kerouac</a>, <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/allen- ginsberg/">Allen Ginsberg</a>, and William S. Burroughs). He was beloved by the other "Beats". “<i>… a tough young kid from the Lower East Side who rose like an angel over the roof tops and sang Italian song as sweet as Caruso and Sinatra, but in words… Amazing and beautiful, Gregory Corso, the one and only Gregory, the Herald.”</i> ~Jack Kerouac <i>"Corso's a poet's Poet, a poet much superior to me. Pure velvet... whose wild fame's extended for decades around the world from France to China, World Poet".</i> ~Allen Ginsberg "<i>Gregory's voice echoes through a precarious future.... His vitality and resilience always shine through, with a light this is more than human: the immortal light of his Muse... Gregory is indeed one of the Daddies". </i>~William S. Burroughs <b>Poetry</b> Corso's first volume of poetry The Vestal Lady on Brattle was published in 1955 (with the assistance of students at Harvard, where he had been auditing classes). Corso was the second of the Beats to be published (after only Kerouac's The Town and the City), despite being the youngest. His poems were first published in the Harvard Advocate. -

An Analysis of the Press Coverage of the Beat Generation During the 1950S Anna Lou Jessmer [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2012 Containing the Beat: An Analysis of the Press Coverage of the Beat Generation During the 1950s Anna Lou Jessmer [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Jessmer, Anna Lou, "Containing the Beat: An Analysis of the Press Coverage of the Beat Generation During the 1950s" (2012). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 427. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTAINING THE BEAT: AN ANALYSIS OF THE PRESS COVERAGE OF THE BEAT GENERATION DURING THE 1950S A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism by Anna Lou Jessmer Approved by Robert A. Rabe, Committee Chairperson Professor Janet Dooley Dr. Terry Hapney Marshall University December 2012 ii Dedication I would like to dedicate my research to my grandfather, James D. Lee. His personal experiences during the Cold War at home and abroad inspired in me a fascination of the era at an early age. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to take a moment to acknowledge in writing, a few individuals without whom this paper would not be complete. I am incredibly and eternally grateful for Professor Robert A.