Digital Recordings and Assessment: an Alternative for Measuring Oral Proficiency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Podcasting? Podcasting Is an Exciting New Way of Publishing Audio Or Video fi Les to the Web

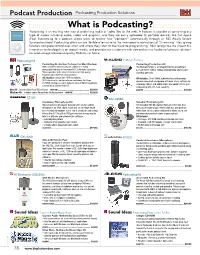

Podcast Production Podcasting Production Solutions What is Podcasting? Podcasting is an exciting new way of publishing audio or video fi les to the web. A Podcast is capable of containing any type of media including audio, video and graphics, and they are easily uploaded to portable devices like the Apple iPod. Subscribing to a podcast allows users to receive new “episodes” automatically through an RSS (Really Simple Syndication) feed. Podcasting offers a more fl exible alternative to the time–specifi c restrictions of “Streaming” fi les; giving listeners complete control over when and where they listen to their favorite programming. B&H recognizes the impact this innovative technology has on today’s media, and provides our customers with comprehensive hardware/software solutions for producing professional–quality Podcasts at home. Podcasting Kit Podcast Factory Podcasting Production Package For Mac/Windows Podcasting Production Kit B&Hs complete hardware/software solution for creating The Podcast Factory is an integrated hardware/software professional Podcasts on Macintosh OS X or Windows computers. package for recording, editing and publishing professional- This kit provides all the tools needed to create high quality, sounding podcasts. inspiring, radio-style Podcast productions. Kit Includes: Samson C01U USB microphone, Kit Includes: 24-bit/48kHz audio interface with preamp, SP01 shock mount, editing software (see below), On-Stage dynamic broadcast microphone with desk stand, software for DS7200B desktop mic stand, Audio-Technica ATHM2X headphones recording, editing, and adding music and sound effects, plus & Sound Ideas Captain Audio CD web posting with RSS feed capability. Mac Kit Includes Bias Peak 5LE software #BHPKM .............................................................. -

Tested Devices 1/7/2008

WMA/DRM 32Kbps compatible Archos Gmini 402 Camcorder Archos 104 Creative ZEN 4GB/8GB/16GB Creative ZEN Stone Creative ZEN Stone Plus Creative ZEN V Creative ZEN V Plus Creative ZEN Vision W Creative ZEN Vision M 60 GB Samsung YP-T7JZ Samsung YP-Z5 Samsung YP-T10 Samsung P2 Samsung YP-S5 Off/On Yes HH:MM:SS Yes Single Title Only Yes 30 - 35 hours 20 Gigs or more $150 - $199 1.2.00 Toshiba Gigabeat S30 Resume Yes HH:MM:SS Yes Two or More Titles Yes 10 - 15 hours 6 Gigs $150 - $199 1.0.31 Yes HH:MM:SS Yes Two or More Titles Yes 20 - 25 hours 15 Gigs $200 - $249 1.11.04 Key: Yes No Time Display Yes Not Supported Yes 10 - 15 hours 1 Gig Yes HH:MM:SS Yes Not SupportedTim Yese Dis 10p hourslay 4 Gigs <$100 1.03.01 Yes HH:MM:SS Yes Two or More Titles Yes 15 - 20 hours 4 Gigs Required Device Features Yes HH:MM:SS Yes Two or More Titles Yes 15 - 20 hours 1 Gig <$100 1.32.01 Highly Recommended Yes HH:MM:SS Yes Two or More Titles Yes 10 - 15 hours 20 Gigs or more >$300 1.10.01 Yes HH:MM:SS Yes Two or More Titles Yes 15 - 20 hours 20 Gigs or more $200 - $299 1.21.02 Lock Option Yes HH:MM:SS Yes Not Supported Yes 10 hours 1 Gig <$100 1.02 US JN Yes HH:MM:SS Yes Not Supported Yes 30 - 35 hours 4 Gigs $200 - $299 1.08 US Optional Yes HH:MM:SS Yes Not Supported Yes 30 - 35 hours 4 Gigs $100 - $149 0.75 Notes Yes HH:MM:SS Yes Not Supported Yes 30 - 35 hours 4 Gigs $150 - $199 US0.52 Yes HH:MM:SS Yes Two or More Titles Yes 20 - 25 hours 4 Gigs $150 - $199 1.01 Bookmarking * Yes HH:MM:SS Yes Not Supported Yes 10 - 15 hours 20 Gigs or more $150 - $199 Rechargeable Battery Tested Devices This Tested Players list represents players we have tested sa important notes and specific features. -

Portable Media Devices Portable Media Devices Douglas Dixon Manifest Technology® LLC

Portable Media Devices Portable Media Devices Douglas Dixon Manifest Technology® LLC October 2006 www.manifest-tech.com 10/2006 Copyright 2005-2006 Douglas Dixon, All Rights Reserved - www.manifest-tech.com Page 1 Portable Media Devices Portable Media to Go Your Digital Life – What’s in your pocket? • Portable Storage –Flash Memory Cards – Flash USB Pocket Drives – Hard Disk Pocket Drives – Portable Hard Drives • Portable Media Players – Stick Music Players – Flash Music Players – Hard Disk Video Players – Portable Media Players • Multi-Function Devices – Mobile Phones – Multimedia PDAs – Portable Game Machines 10/2006 Copyright 2005-2006 Douglas Dixon, All Rights Reserved - www.manifest-tech.com Page 2 1 Portable Media Devices iPod Chronology – Hard Disk iPod HD 5GB 10G 15G 20G 30G 40G 60G 80G 10/01 iPod 1 $399 mono, 6.5 oz. 3/02 iPod 1 $399 $499 7/02 iPod 2 $299 $299 - $499 iPod 1, 10/01 4/03 iPod 3 - $299 $399 - $499 iPod 2, 7/02 iPod 3, 4/03 10/03 iPod 3 - $299 - $399 - $499 1/04 iPod 3 - - $299 $399 - $499 iPod 4, 7/04 7/04 iPod 4 - - - $299 - $399 click wheel 10/04 Photo - - - - - $499 $599 color 2”, 220x176 2/05 Photo 2 iPod- Photo, 10/04- - - $349 - $449 ~6 oz 6/05 iPod color - - - $299 - - $399 5.6 oz. 2.5", 320x240 6/05 iPod video - - - - $299 - $399 4.8/5.5 oz. 9/06 iPod video iPod video, 6/05 $249 $349 60% brighter 10/2006 Copyright 2005-2006 Douglas Dixon, All Rights Reserved - www.manifest-tech.com Page 3 Portable Media Devices iPod Chronology - Flash Mini HD -> Flash iPod Flash 512M 1GB 2GB 4GB 6GB 4GB 2/04 Mini 1 - - - $249 mono, 3.6 oz. -

AVS Video Converter V.6

AVS4YOU Help - AVS Video Converter v.6 AVS4YOU Programs Help AVS Video Converter v.6 www.avs4you.com © Online Media Technologies, Ltd., UK. 2004 - 2009 All rights reserved AVS4YOU Programs Help Page 2 of 167 Contact Us If you have any comments, suggestions or questions regarding AVS4YOU programs or if you have a new feature that you feel can be added to improve our product, please feel free to contact us. When you register your product, you may be entitled to technical support. General information: [email protected] Technical support: [email protected] Sales: [email protected] Help and other documentation: [email protected] Technical Support AVS4YOU programs do not require any professional knowledge. If you experience any problem or have a question, please refer to the AVS4YOU Programs Help. If you cannot find the solution, please contact our support staff. Note: only registered users receive technical support. AVS4YOU staff provides several forms of automated customer support: AVS4YOU Support System You can use the Support Form on our site to ask your questions. E-mail Support You can also submit your technical questions and problems via e-mail to [email protected]. Note: for more effective and quick resolving of the difficulties we will need the following information: Name and e-mail address used for registration System parameters (CPU, hard drive space available, etc.) Operating System The information about the capture, video or audio devices, disc drives connected to your computer (manufacturer and model) Detailed step by step describing of your action Please do NOT attach any other files to your e-mail message unless specifically requested by AVS4YOU.com support staff. -

El Laboratorio Profeco Reporta

EL LABORATORIO PROFECO REPORTA Foto 66archivo Consumidor • Octubre 2008 Reproductores portátiles de música MP3 y de video MP4 Los actuales reproductores portátiles de música MP3 son una maravilla de la tecnología, pues permiten llevar en el bolsillo miles de canciones, fotos y videos, e incluso permi- ten escuchar radio y grabar voz. Por lo mismo, dada la gran variedad de opciones que ofrece el mercado, no es sencillo escoger aquel que por atributos y calidad resulta más ade- cuado a las necesidades del consumidor. Para orientarlo al respecto, este análisis le informa sobre la calidad, funciones y características de estos aparatos. Octubre 2008 • Consumidor 67 En menos de una década, los re- En el mercado existen distintos MP4 que reproducen tanto música productores portátiles han cam- tipos de reproductores portátiles en formato MP3 como video en biado la forma como escuchamos de música MP3; en este estudio se formato MPEG-4. Todos se comer- música; más aún, siguen evolu- clasificaron en dos categorías que cializan en el país. cionando hacia aparatos de en- comparten la capacidad de repro- Cada modelo se sometió a seis tretenimiento personal “todo en ducir música MP3: aquellos que son pruebas, cuyos resultados se agru- uno”, ya que no sólo han reem- capaces de reproducir video en el paron de la manera siguiente: plazado a los anteriores repro- formato MPEG-4 (denominados re- Información al consumidor. La eti- ductores de cintas y de CD-audio productores MP4) y los que carecen queta del aparato tiene que informar portátiles, sino que han integrado de esta función (llamados reproduc- sobre el tipo de producto, marca, dentro de sus capacidades poder es- tores MP3). -

2 Portable Entertainment

Section2 PHOTO - VIDEO - PRO AUDIO Portable Entertainment PORTABLE AUDIO & VIDEO Apple..........................................................24-30 Belkin..........................................................31-33 DLO .............................................................34-35 Griffin Technology ............................36-39 iPod Accessories..................................40-51 Archos .........52-53 Samsung....64-65 Creative ......54-57 SanDisk.......66-67 iAudio..........58-62 Sony..............68-70 Microsoft...........63 Toshiba...............71 PORTABLE DVD PLAYERS Audiovox ..........72 Panasonic..74 -75 Initial DVD........73 Sony.....................76 Toshiba ............................................................77 Obtaining information and ordering from B&H is quick and easy. When you call us, just punch in the corresponding Quick Dial number anytime during our welcome message. The Quick Dial code then directs you to the specific professional sales associates in our order department. For Section 2, Portable Entertainment, use Quick Dial #: 94 24 PERSONAL AUDIO APPLE iPOD NANO (2ND GENERATION) 2-, 4- and 8GB Pencil-Thin Digital Music/Photo Players A thinner design. Five stylish colors. A brighter display. Up to 24 hours of battery life. Everything you loved about the original iPod nano but better. Available in three storage sizes 2GB (500 songs), 4GB (1,000 songs) and 8GB (2,000 songs), the pencil-thin iPod nano packs the entire iPod experience into an impossibly small design. How small? At 0.26” from front to back, the iPod nano is about as deep as six stacked credit cards. Impossible? Pick it up and hold it in your hand. Take in the brilliant color display— 40% brighter that the original, run your thumb around the Click Wheel. Put on the earbuds and turn up your music. 8GB of skip-free storage on a featherweight iPod means you can wear almost five days’ worth of music around your neck.