Abraham Lincoln Pointed out That the Alliance Between Republicans And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Urban Frontier in Pioneer Indiana ROBERT G

The Urban Frontier in Pioneer Indiana ROBERT G. BARROWS AND LEIGH DARBEE ne of the central themes of Richard Wade’s The Urban Frontier— Othat the “growth of urbanism was an important part of the occupa- tion of the West”—has been reflected in Indiana historiography only occasionally. Donald F. Carmony’s examination of the state from 1816 to mid-century is definitive on constitutional, financial, political, and transportation topics, but is much less informative concerning social and urban history; indeed, Wade’s book does not appear in Carmony’s bibliography. In his one-volume history of the state, The Indiana Way, James H. Madison echoes Wade when he writes: “Towns were an essen- tial part of frontier development . providing essential services to the rural and agricultural majority of Indiana’s population.”1 When one con- siders the history of cities and towns in pioneer Indiana in relation to Wade’s classic work, a “generation gap” becomes readily apparent. Developments in Indiana (and, notably, in Indianapolis, the closest comparison to the cities Wade examined) run two or three decades behind his discussion of urbanism in the Ohio Valley. Wade begins his __________________________ Robert G. Barrows is chair of the Department of History at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and co-editor, with David Bodenhamer, of The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (1994). Leigh Darbee is executive assistant at the Indiana Rail Road Company, Indianapolis, and the author of A Guide to Early Imprints at the Indiana Historical Society, 1619- 1840 (2001). 1Richard C. Wade, The Urban Frontier: The Rise of Western Cities, 1790-1830 (Cambridge, Mass., 1959), 2; Donald F. -

540 Virginia Ave. Indianapolis, IN

Fletcher Place www.fletcherplace.org May / June 2009 Infrastructure work The dirt on the Garden Committee The Fletcher Place moves forward Garden Committee, led A stroll along by Rhonda Peffer, has East Street in planned two opportunities front of the Vil- for neighbors to become laggio won’t be involved, with other events perilous any- to be announced. more thanks to First up is Adopt-A- the improve- Block through Keep India- ments made by napolis Beautiful, KIB. A DPW. Fletcher volunteer block coordina- Place’s “worst tor is given tools and trash sidewalk” is bags that can be used to now its best. The keep his/her assigned Fletcher Place block free of trash and Neighborhood debris. KIB will monitor Association’s and score blocks monthly and offer advice and sug- and David Edy at 526 S. Infrastructure through October, and will gestions. If you have plants Pine St. C o m m i t t e e , award high-scoring blocks that need thinning or split- For information on the comprised of with plantings, trees, mini ting, bring them to share. Garden Committee, to Adopt- Robb Biddinger, grants, and other goodies No reservations needed, A-Block, or share your sug- Rick McQuery Attention everyone, it’s okay to walk on to help with neighbor- just join us! gestions for garden events, and Jeff Miller, the sidewalk at Villaggio now. hood beautification. Thank Our second visit will contact Rhonda Peffer at helped identify the areas you to FP neighbors who be June 7 at 4 p.m. at the [email protected]. -

Emma Lou Thornbrough Manuscript, Ca 1994

Collection # M 1131 EMMA LOU THORNBROUGH MANUSCRIPT, CA 1994 Collection Information Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Note Contents Cataloging Information Processed by Kelsey Bawel 26 August 2014 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF 1 document case COLLECTION: COLLECTION ca. 1994 DATES: PROVENANCE: RESTRICTIONS: None COPYRIGHT: REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE FORMATS: RELATED HOLDINGS: ACCESSION 2007.0085 NUMBER: NOTES: BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Emma Lou Thornbrough (1913-1994), an Indianapolis native, graduated from Butler University with both a B.A. and an M.A. She went on to the University of Michigan where she received her Ph.D. in 1946. Following graduation, Thornbrough began teaching at Butler until her retirement in 1983. During her career at Butler, she held visiting appointments at Indiana University and Case Western Reserve University. Thornbrough’s research is exemplified in her two main works: The Negro in Indiana before 1900 (1957) and Indiana in the Civil War (1965). She engaged the community by writing numerous articles focusing on United States constitutional history and race as a central force in the nation’s development. Thornbrough was also active in various community organizations including the Organization of American Historians, Southern Historical Association, Indiana Historical Society, Indiana Association of Historians, Indiana Alpha Association of Phi Beta Kappa, American Association of University Professors, Indiana Civil Liberties Union, Indianapolis Council of World Affairs, Indianapolis NAACP, and the Indianapolis Human Relations Council. -

Visit Indy Downtown Restaurant

DOWNTOWN INDIANAPOLIS RESTAURANTS IU Health North St. North St. University 110 Hospital Veterans Old 149 87 137 Memorial National 126 84 P 51 117 57 45 109 Plaza 14 31 Blake St. Centre 146120 Michigan St. Michigan St. P Indianapolis CulturalTrail P P P 29 20 Indiana 46 38 Map sponsored by: World 55 78 Massachusetts94 Ave. Capitol Ave. War 148 James Whitcomb Memorial Indiana University 23153 Riley Museum Purdue University Indianapolis Vermont St. 9 P (IUPUI) 108 106 Courtyard 97 63 by Marriott 107 69 48 86P ★ indicates PNC ATM locations St. West Meridian St. University Pennsylvania St. Delaware St. Senate Ave. Illinois St. East St. College Ave. New Jersey St. Residence 5 116 Alabama St. University Blvd. Blackford St. Inn by Park Barnhill Dr. 138 Marriott 43 93 New York St. New York St. IU Michael A. Carroll IU Indiana 66 16 Track & Soccer Stadium 82 Natatorium History Easley Military Center 75 P 21 19 P 30 Winery Blake St. W Ohio St. hite Riv Park er Wapah Columbia Club ani T ★ Sheraton 50 ★58 rail Sun King P 3 Hilton 71 City Brewery Hilton Home2 70 Central Canal Garden Suites Market 72 White River 1 Inn 8 P Indiana Indiana 67 State Monument P State Eiteljorg Market St. White River NCAA Headquarters Museum Capitol 142 Circle ★ & Hall of Champions Museum 34 42 152 119 52 121 15 127 & IMAX Embassy 118 Theater68 88 98 74 ★ State Park Suites Conrad 139 99 P 7 147 27 10454 18151P 125 P Washington St. P ? 129 143 Parking 77 133 ★47 6 ★ 28 140 Transit 25 Garage 41 Hyatt Circle 131 Center LaQuinta Indianapolis Zoo & Marriott Westin 124 76 Inn White River Gardens ? JW Marriott Regency Centre123 26 P 13 P Mall 105134 145 INT Maryland St. -

Kentucky: Mother of Governors

Kentucky' M other of Governors K e n t ucky ' M o th e r o f G o ve rn o rs JOHN WILSON TOWNSEND an Au thor of Richard Hickman Mene fee Ke ntuckians in H istory a n d Literature The Life of James Francis Leonard Etc The Ken tucky State Historical Society r n kfort Ke k F a , n tuc y 1 9 1 0 ' Editor s Introduction H I F I T S , THE RS volume of the Kentucky — Historical Series a series j ust inaugur ated by the Kentucky State Historical — Society is a study of Kentucky initiative in the United States as exemplified in these more than one hundred sons of o u r Commonwealth who have served as Governors of other States a n d territories . Mr . Townsend has realized that the list is the important thing, and he has made an earnest effort to have it complete . For this reason he has been content W ith sketches in miniature of each executive , knowing that , had he attempted anything like an adequate notice of each man , his paper would have become an octavo . The E ditor of this series believes that Kentucky ' Mother of Governors is a creditable piece of work ; something new under the Kentucky history sun ; and well suited to be the first in a series of books that the Kentuck y State Historical Society will issue from time to time . R RT M S . JE NNIE C . M O ON Th e K en tu ck y S ta t e H is t or i ca l S ociety F r a n k or K en tuck f t , y ’ Author s ' refatory Note HIS ' A' E R IS the result of a summer ’ day s browsing in a public library . -

African-American Education in Indiana State of Indiana Researcher: John Taylor

African-American Education in Indiana State of Indiana Researcher: John Taylor African-American Education in Indiana The African-American experience in the United Stated includes a vast array of social, cultural and political injustices during the past four-hundred years. Slavery most famously represents the hardships African-Americans faced, but their plight went beyond the typified southern plantation fields. African Americans endured the rigors of an unequal social system in various forms, such as the absence of suffrage. Indiana never legally installed slavery as an institution, but the state tolerated slave owning, and blacks still suffered from racist attitudes and unfair laws within its boundaries.1 An example of Indiana’s racial bias is this short case study of the state’s educational legislation and school segregation. Since the state’s admission to the union in 1816 to the present day African- American education has been an issue debated in numerous township halls, school board meetings and the Indiana General Assembly. The 1816 Constitution of Indiana stated “as soon as circumstances will permit, to provide by law for a general system of education, ascending in a regular gradation from township schools to a State University, wherein tuition shall be gratis, and equally open to all.”2 In theory, a vast systemized educational system was a much needed program in the budding new state, but little progress materialized. Instead, according to historian Emma Lou Thornbrough, Indiana became one of the most backward states in providing necessary resources for public schools before the Civil War. White children received limited educational opportunities: while colored children were denied antiquate public educational facilities.3 In 1850, once Indiana outgrew the 1816 State Constitution, members of the constitutional convention debated about the needed revisions to the state’s governmental system. -

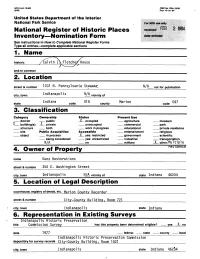

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3*2) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections______________ 1. Name historic talvin I\ Fletche/House and/or common 2. Location street & number 1031 N - Pennsylvania not for publication city, town Indianapolis vicinity of 018 state Indiana code county Marion code 097 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public _X _ occupied agriculture museum X building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation N/A no military JLotherMultiple 4. Owner off Property residence name Kunz Restorations street & number 350 E. Washington Street city, town Indianapolis N/A. vicinity of state Indiana 46204 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Marion County Recorder street & number City-County Building, Room 721 city, town Indianapolis state Indiana 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Indianapolis Historic Preservation title Commission Survey____________has this property been determined eligible? yes JL no date 1977 federal state county local Indianapolis Historic Preservation Commission depository for survey records City-County Building, Room 1821___________. city, town Indianapolis state Indiana 462&4 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered * original site X good ruins X altered moved date N/A fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Located at 1031 N. -

Alvin P. Hovey and Abraham Lincoln's “Broken

Alvin P. Hovey and Abraham Lincoln’s “Broken Promises”: The Politics of Promotion Earl J. Hess* The promotion of Alvin P. Hovey to brevet major general of volunteers in July, 1864, was an incident of some note during the Civil War’s Atlanta campaign. Angered by what he considered a political favor given to an unworthy officer, General William T. Sherman protested vigorously. President Abraham Lincoln, who had granted the promotion, responded, and historians have used this exchange to illustrate the personalities of both men. Thus overshadowed, Hovey’s case receded into obscurity.’ It is unfortunate that Hovey’s promotion, as such, has not received more attention, for his story is informative concerning the way in which military appointments in the Civil War were intertwined with political considerations. Hovey’s was not a sim- plistic case of military patronage, as Sherman believed, but an illustration of the mutable boundaries between politics and the military in a citizen army and the effects of that combination on the life of a man who successfully worked in both spheres. Hovey was a political general as were John A. Logan, Frank P. Blair, and other northwesterners. Unlike them, he failed to make max- imum use of his talents as politician and as general to achieve advancement of the kind he desired. Hovey’s antebellum career established him as a significant personality in Indiana politics. Born in 1821 near Mount Vernon, Indiana, Hovey practiced law before embarking on a brief tour of duty in the Mexican War. He was a Democratic delegate to the * Earl J. -

Booker T. Washington and the Historians

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2015 Booker T. Washington and the Historians: How Changing Views on Race Relations, Economics, and Education Shaped Washington Historiography, 1915-2010 Joshua Thomas Zeringue Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Zeringue, Joshua Thomas, "Booker T. Washington and the Historians: How Changing Views on Race Relations, Economics, and Education Shaped Washington Historiography, 1915-2010" (2015). LSU Master's Theses. 1154. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/1154 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOKER T. WASHINGTON AND THE HISTORIANS: HOW CHANGING VIEWS ON RACE RELATIONS, ECONOMICS, AND EDUCATION SHAPED WASHINGTON HISTORIOGRAPHY, 1915-2010 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Joshua Thomas Zeringue B.A., Christendom College, 2010 December 2015 To Monica, Sam, and Noah. Tu ne cede malis, sed contra audentior ito. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When I was twelve years old my father gave me a piece of advice. “Son,” he said, “whenever you read a book, be sure to note when it was written.” Though I did not understand at the time, my father had taught me the most basic principle of historiography. -

Crown Hill Walking Tour of Indianapolis' Bicentennial Notables

2020 Crown Hill Walking Tour of Indianapolis’ Bicentennial Notables 1. Alexander Ralston (1771-1827) Born in Scotland, Ralston immigrated to the U.S. following the Revolutionary War. He served as personal assistant to Pierre L’Enfant in 1791 during his planning for Washington, D.C. Hired in 1820 to survey land for Indianapolis on a 4-mile plat of dense forest. Inspired by his work with L’Enfant, he designed a Mile Square plan consisting of a central circle with four radiating avenues bisecting a grid of streets. Lot 30, Section 3 (Pictured) 2. John Washington Love (1850-1880) The artist’s palette on the side of Love Family monument is a fitting tribute to this artist. He was the co-founder of the first professional art school in Indianapolis and Indiana. Unfortunately, death at age 30 from “congestion of the stomach” cut short what might have been a very noted career as a painter. Lot 3, Section 3 3. Richard J. Gatling, M.D. (1818-1903) Doctor and prolific inventor best known for his invention of the Gatling gun in 1861, considered the first successful machine gun. He believed his invention would end all wars. Lot 9, Section 3 4. Hiram Bacon (1801-1881) His farm included an area still called Bacon’s Swamp, now a lake just west of Keystone between Kessler and 54th Street in the middle of a retirement community. According to some sources, he used his barn as a stop on the Underground Railroad. Lot 43, Section 3 5. Horatio Newcomb (1821-1882) Indianapolis elected its first mayor in 1847, Samuel Henderson, who left town in 1849 in pursuit of California Gold. -

Black History News & Notes

BLACK HISTORY NEWS & NOTES NOVEMBER 2001 NUMBER 86 “Probably a Thousand Cats Are Using Their Thumbs”: A Brief Biographical Sketch of Wes Montgomery Andrew M. Mills Jazz historian Ted Gioia observed legacy. Often forgotten in all of these that modem jazz artists “developed accolades, however, is the story of their own unique style, brash and un- Wes Montgomery’s stmggles during apologetic, in backrooms and after his early years in Indianapolis. For hours clubs, at jam sessions and on tunately, some sense of those days can the road with traveling bands.” The be regained through examination of earliest performers of this brand of existing interviews; the most impor music “were, at best, cult figures from tant, perhaps, in Jazz Monthly in May beyond the fringe, not household 1965. names.”1 According to Gioia, a few Bom in Indianapolis on 6 March of these fringe musicians would pass 1923, the musician was originally on to musical greatness, their work named John Leslie Montgomery. He Wes Montgomery. Indianapolis coming to define a particular brand adopted the name Wes later in life. Recorder Collection, IHS C8806 of music for generations to come. Montgomery never received any for discovering “that was more trouble Perhaps no other modem artist fits mal musical training. He could not than I’d ever had in my life! I didn’t Gioia’s description more accurately read notation or chord symbols want to face that. It let me know than jazz guitarist Wes Montgomery. throughout his entire life. At twelve where I really was. It was disappoint A humble man, Montgomery once his brother bought him a tenor guitar ing.” Fortunately, the future India observed of his unique thumb-play that had four strings. -

Breaking Racial Barriers to Public Accommodations in Indiana, 1935 to 1963

Breaking Racial Barriers to Public Accommodations in Indiana, 1935 to 1963 Emma Lou Thornbrough” I went into a restaurant today and asked for a sandwich. The waitress told me she could not serve me. Had this place been a top hat and tail’s place I would not have gone in. But it’s in the midst of the steel district and only the workers go there. I am working in the same block as the restaurant, and I felt like it was all right for me to go in. I was clean. Thus wrote an East Chicago woman to Walter White, secre- tary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), in 1943, a year when the United States was en- gaged in a desperate war against Nazi Germany, a fascist, racist power. “Mr. White,” the writer continued, “we have any number of places in Indiana Harbor, E. Chicago and Hammond. Some even display signs in there [sic]windows ‘white only.’ ” She asked White for guidance as to action that might be taken in the face of wide- spread discrimination, adding: “We need some action out here. I don’t want riots or anything like that. But I do want justice for all, and I don’t believe in any isms but Americanisms. I want my six- teen year old son to know the true meaning of Americanism by seeing it practiced toward men regardless of color.”’ Other letters about racial discrimination and segregation in Indiana came regularly to the national office of the NAACP. Blacks complained of exclusion from eating places.‘ They were rarely al- lowed to sit down at lunch counters or tables, although some estab- lishments permitted them to buy food to carry off the premises.