Black History News & Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Urban Frontier in Pioneer Indiana ROBERT G

The Urban Frontier in Pioneer Indiana ROBERT G. BARROWS AND LEIGH DARBEE ne of the central themes of Richard Wade’s The Urban Frontier— Othat the “growth of urbanism was an important part of the occupa- tion of the West”—has been reflected in Indiana historiography only occasionally. Donald F. Carmony’s examination of the state from 1816 to mid-century is definitive on constitutional, financial, political, and transportation topics, but is much less informative concerning social and urban history; indeed, Wade’s book does not appear in Carmony’s bibliography. In his one-volume history of the state, The Indiana Way, James H. Madison echoes Wade when he writes: “Towns were an essen- tial part of frontier development . providing essential services to the rural and agricultural majority of Indiana’s population.”1 When one con- siders the history of cities and towns in pioneer Indiana in relation to Wade’s classic work, a “generation gap” becomes readily apparent. Developments in Indiana (and, notably, in Indianapolis, the closest comparison to the cities Wade examined) run two or three decades behind his discussion of urbanism in the Ohio Valley. Wade begins his __________________________ Robert G. Barrows is chair of the Department of History at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and co-editor, with David Bodenhamer, of The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (1994). Leigh Darbee is executive assistant at the Indiana Rail Road Company, Indianapolis, and the author of A Guide to Early Imprints at the Indiana Historical Society, 1619- 1840 (2001). 1Richard C. Wade, The Urban Frontier: The Rise of Western Cities, 1790-1830 (Cambridge, Mass., 1959), 2; Donald F. -

540 Virginia Ave. Indianapolis, IN

Fletcher Place www.fletcherplace.org May / June 2009 Infrastructure work The dirt on the Garden Committee The Fletcher Place moves forward Garden Committee, led A stroll along by Rhonda Peffer, has East Street in planned two opportunities front of the Vil- for neighbors to become laggio won’t be involved, with other events perilous any- to be announced. more thanks to First up is Adopt-A- the improve- Block through Keep India- ments made by napolis Beautiful, KIB. A DPW. Fletcher volunteer block coordina- Place’s “worst tor is given tools and trash sidewalk” is bags that can be used to now its best. The keep his/her assigned Fletcher Place block free of trash and Neighborhood debris. KIB will monitor Association’s and score blocks monthly and offer advice and sug- and David Edy at 526 S. Infrastructure through October, and will gestions. If you have plants Pine St. C o m m i t t e e , award high-scoring blocks that need thinning or split- For information on the comprised of with plantings, trees, mini ting, bring them to share. Garden Committee, to Adopt- Robb Biddinger, grants, and other goodies No reservations needed, A-Block, or share your sug- Rick McQuery Attention everyone, it’s okay to walk on to help with neighbor- just join us! gestions for garden events, and Jeff Miller, the sidewalk at Villaggio now. hood beautification. Thank Our second visit will contact Rhonda Peffer at helped identify the areas you to FP neighbors who be June 7 at 4 p.m. at the [email protected]. -

Visit Indy Downtown Restaurant

DOWNTOWN INDIANAPOLIS RESTAURANTS IU Health North St. North St. University 110 Hospital Veterans Old 149 87 137 Memorial National 126 84 P 51 117 57 45 109 Plaza 14 31 Blake St. Centre 146120 Michigan St. Michigan St. P Indianapolis CulturalTrail P P P 29 20 Indiana 46 38 Map sponsored by: World 55 78 Massachusetts94 Ave. Capitol Ave. War 148 James Whitcomb Memorial Indiana University 23153 Riley Museum Purdue University Indianapolis Vermont St. 9 P (IUPUI) 108 106 Courtyard 97 63 by Marriott 107 69 48 86P ★ indicates PNC ATM locations St. West Meridian St. University Pennsylvania St. Delaware St. Senate Ave. Illinois St. East St. College Ave. New Jersey St. Residence 5 116 Alabama St. University Blvd. Blackford St. Inn by Park Barnhill Dr. 138 Marriott 43 93 New York St. New York St. IU Michael A. Carroll IU Indiana 66 16 Track & Soccer Stadium 82 Natatorium History Easley Military Center 75 P 21 19 P 30 Winery Blake St. W Ohio St. hite Riv Park er Wapah Columbia Club ani T ★ Sheraton 50 ★58 rail Sun King P 3 Hilton 71 City Brewery Hilton Home2 70 Central Canal Garden Suites Market 72 White River 1 Inn 8 P Indiana Indiana 67 State Monument P State Eiteljorg Market St. White River NCAA Headquarters Museum Capitol 142 Circle ★ & Hall of Champions Museum 34 42 152 119 52 121 15 127 & IMAX Embassy 118 Theater68 88 98 74 ★ State Park Suites Conrad 139 99 P 7 147 27 10454 18151P 125 P Washington St. P ? 129 143 Parking 77 133 ★47 6 ★ 28 140 Transit 25 Garage 41 Hyatt Circle 131 Center LaQuinta Indianapolis Zoo & Marriott Westin 124 76 Inn White River Gardens ? JW Marriott Regency Centre123 26 P 13 P Mall 105134 145 INT Maryland St. -

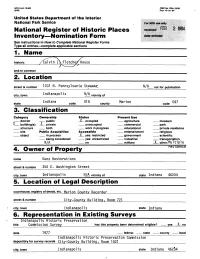

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3*2) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections______________ 1. Name historic talvin I\ Fletche/House and/or common 2. Location street & number 1031 N - Pennsylvania not for publication city, town Indianapolis vicinity of 018 state Indiana code county Marion code 097 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public _X _ occupied agriculture museum X building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation N/A no military JLotherMultiple 4. Owner off Property residence name Kunz Restorations street & number 350 E. Washington Street city, town Indianapolis N/A. vicinity of state Indiana 46204 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Marion County Recorder street & number City-County Building, Room 721 city, town Indianapolis state Indiana 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Indianapolis Historic Preservation title Commission Survey____________has this property been determined eligible? yes JL no date 1977 federal state county local Indianapolis Historic Preservation Commission depository for survey records City-County Building, Room 1821___________. city, town Indianapolis state Indiana 462&4 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered * original site X good ruins X altered moved date N/A fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Located at 1031 N. -

Crown Hill Walking Tour of Indianapolis' Bicentennial Notables

2020 Crown Hill Walking Tour of Indianapolis’ Bicentennial Notables 1. Alexander Ralston (1771-1827) Born in Scotland, Ralston immigrated to the U.S. following the Revolutionary War. He served as personal assistant to Pierre L’Enfant in 1791 during his planning for Washington, D.C. Hired in 1820 to survey land for Indianapolis on a 4-mile plat of dense forest. Inspired by his work with L’Enfant, he designed a Mile Square plan consisting of a central circle with four radiating avenues bisecting a grid of streets. Lot 30, Section 3 (Pictured) 2. John Washington Love (1850-1880) The artist’s palette on the side of Love Family monument is a fitting tribute to this artist. He was the co-founder of the first professional art school in Indianapolis and Indiana. Unfortunately, death at age 30 from “congestion of the stomach” cut short what might have been a very noted career as a painter. Lot 3, Section 3 3. Richard J. Gatling, M.D. (1818-1903) Doctor and prolific inventor best known for his invention of the Gatling gun in 1861, considered the first successful machine gun. He believed his invention would end all wars. Lot 9, Section 3 4. Hiram Bacon (1801-1881) His farm included an area still called Bacon’s Swamp, now a lake just west of Keystone between Kessler and 54th Street in the middle of a retirement community. According to some sources, he used his barn as a stop on the Underground Railroad. Lot 43, Section 3 5. Horatio Newcomb (1821-1882) Indianapolis elected its first mayor in 1847, Samuel Henderson, who left town in 1849 in pursuit of California Gold. -

Downtown Indianapolis Restaurant Sites

Downtown Indianapolis Restaurant Sites Maxine's Chicken and Waffles 132 N East St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Barcelona Tapas 201 N Delaware St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Saffron Cafe 621 Fort Wayne Avenue, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Downtown Olly's 822 N Illinois St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Bourbon Street Restaurant & Distillery 361 N Indiana Ave, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Iaria's Italian Restaurant 317 S College Ave, Indianapolis, IN 46202 South of Chicago Pizza & Beef 619 Virginia Avenue, Indianapolis, IN 46203 Bluebeard 653 Virginia Ave, Indianapolis, IN 46203 Acapulco Joe's Mexican Food 365 N Illinois St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Tortas Guicho Dominguez y el Cubanito 641 Virginia Avenue, Indianapolis, IN 46203 City Cafe 443 N Pennsylvania St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 India Garden 207 N Delaware St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Le Peep 301 N Illinois St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Milano Inn 231 S College Ave, Indianapolis, IN 46202 Elbow Room Pub & Deli 605 N Pennsylvania St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Ralph's Great Divide 743 E New York St, Indianapolis, IN 46202 English Ivy's 944 N Alabama St, Indianapolis, IN 46202 Hong Kong 1524 N Illinois St, Indianapolis, IN 46202 Milktooth 534 Virginia Ave, Indianapolis, IN 46203 Bangkok Restaurant & Jazz Bar 225 East Ohio St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Datsa Pizza 907 N Pennsylvania St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Plow and Anchor 43 9th St, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Calvin Fletcher's Coffee Company 647 Virginia Ave, Indianapolis, IN 46203 Sahm's Tavern 433 N. Capitol, Indianapolis, IN 46204 Bearcats Restaurant 1055 N Senate Ave, Indianapolis, -

The Indiana State House a Self-Guided Tour

The Indiana State House A Self-Guided Tour History Completed in 1888, the The Indiana Territory was carved in 1800 from the Northwest Territory. The new territory State House is home to contained all of what is now Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, a great portion of Michigan and officials from all three part of Minnesota. The first seat of government for the Indiana Territory was located in branches of government: Vincennes (1800-1813); the government building, believed to have been built in 1800, is executive, legislative and now a State Historic Site. judicial. The seat of government was moved to Corydon in 1813. Corydon was a logical choice at To become acquainted with the time because settlers and supplies heading west arrived via the Ohio River a short this important and historic distance away. Indiana became a state on December 11, 1816, and Corydon remained the building, begin by exploring seat of government. The original State House is now a State Historic Site. It was built at some State House history. a cost of $3,000. The building was made of Indiana limestone. Certain areas are not Although it was the state’s first seat of government, no one from Corydon had ever served available for viewing as governor until Frank O’Bannon was elected in 1996. without the presence of a As more roads were built and settlement moved northward, a centrally located seat of State House Tour Guide. government was needed. In January 1821 the site where Indianapolis is now located was These areas include the designated as such, and the city was created. -

The Diary of Calvin Fletcher and the Historians George W

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons @ Butler University Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS College of Liberal Arts & Sciences 1998 The Diary of Calvin Fletcher and the Historians George W. Geib Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/facsch_papers Part of the Military History Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Geib, George W., "The Diary of Calvin Fletcher and the Historians" Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History / (1998): 23-25. Available at http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/facsch_papers/791 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "In former years I kept a Journal or diary of the occurrancies of life and important THE DIARY OF CALVIN FLETCHER AND THE HISTORIANS dai[l]y transactions. And I now most sincerely regret that I had not continued the r;Jeorge r;Jeib same with regularity and care down to the present piriod, at the age of thirty one (in "In the summer of1821 the Delaware Indians left the central part of Indiana then a total wilder Feb. next). Many transactions worthy of note -

A TALE of TWO ORPHANAGES: CHARITY in NINETEENTH-CENTURY INDIANAPOLIS Emily Anne Engle Submitted to the Faculty of the Universit

A TALE OF TWO ORPHANAGES: CHARITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY INDIANAPOLIS Emily Anne Engle Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History Indiana University May 2018 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee _______________________________ Anita Morgan, Ph.D., Chair _______________________________ Katherine Badertscher, Ph.D. _______________________________ Nancy Marie Robertson, Ph.D. ii Acknowledgements The advice, support, and encouragement of many people fueled this project to completion. My gratitude to the individuals who helped me along this journey extends far beyond these short acknowledgements. Before I started the graduate program, Dr. Anita Morgan encouraged me to write a thesis when I was hesitant to try. She also guided me through the difficult situation of changing my thesis topic halfway through the program. She read draft after draft, provided prompt and invaluable comments, and was patient when I fell behind my deadlines. This paper would not exist were it not for her. Thank you, Anita. Dr. Katherine Badertscher and Dr. Nancy Robertson also provided invaluable guidance. Kathi read multiple drafts and offered helpful critiques of my writing. Nancy read my work and offered comments, while also ensuring that I met all of the program requirements (no small feat!). A sincere thanks goes to the helpful and dedicated staff in the Collections Department at the Indiana Historical Society who made my countless hours of research much less difficult. Thank you for all that you do! To the many friends who encouraged and prayed for me when I despaired over this project, thank you from the bottom of my heart (you know who you are). -

Carrington and the Golden Circle Legend in Indiana During the Civil War

Carrington and the Golden Circle Legend in Indiana during the Civil War Frank L. Klenzent" Indiana contributed more than any other state to the building of the legend that the Knights of the Golden Circle, as a subversive society, existed in the upper Middle West during the Civil War years. No one in Indiana made as great a contribution to the Golden Circle fantasy as Henry B. Carrington, onetime politician, soldier, and man of letters. When Governor Oliver P. Morton appointed Carrington, in midyear of 1862, to speed up the recruitment and organiza- tion of Indiana troops, the ex-Ohioan could look back upon an active and checkered career. He had practiced law in Columbus, Ohio, with considerable success. He had dabbled in the study of military tactics, contributing a guide on regula- tions and troop maneuvers. He had become an avowed aboli- tionist and had helped to bring the Republican party into being in Ohio. Then, when William Dennison had become governor of Ohio, he had named Carrington, a onetime law partner, as his adjutant general. The highhanded tactics of the two created considerable resentment and also ruffled the feelings of the Secretary of War.= Carrington defied the orders of Secretary Simon Cameron, for he organized more regiments than Ohio's quota early in 1861. When David Tod replaced Dennison in the governor's chair early in 1862, Carrington sought an army commission; and he received the colonelcy of the Eighteenth Regiment, United States troops. Shortly thereafter, Governor Morton secured the services of Colonel Carrington; and he came to Indianapolis to a desk and a duty.e *Frank L. -

This Must Be the Place Brent T Aldrich Submitted to the Faculty of The

this must be the place Brent T Aldrich Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts in Visual Art and Public Life in the Herron School of Art and Design Indiana University May 2018 Where to begin? With you, and with me. This place. This city/this bedrock. It’s Devonian Era limestone over here. “There’s coffee for those who want it.” “Home is where I want to be / but I guess I’m already there. I come home / she lifted up her wings I guess that this must be the place. I can’t tell one from another Did I find you or you find me? There was a time / before we were born If someone asks, this is where I’ll be Where I’ll be.” —Talking Heads _________________ As my practice has evolved, it has become deeply rooted first in my own experiences in the world, and navigating the ways I’m part of a neighborhood, a place, communities and sub- cultures, city. It’s rooted in a desire to connect deeply with other people and the particular places I care about—in this sense, it begins with experiences that are affective and empathetic, even as they are necessarily filtered through my own perceptual-experiential- relational understanding. The primary locus of these projects is centered on experiences in which I have direct exchanges with other human beings, or a particular place, and fabricate contexts for those experiences to be made visible, shared, and expanded. -

Fridaymay10 the Indianapolis Cultural Trail

3. TERRENCE CAMPBELL / TRE CLUB DESIGNS 4. JAVIER BARRERA / LATINO YOUTH COLLECTIVE. ART DIRECTION BY ANDY FRY / BIG CAR ART + DESIGN. ART / BIG CAR FRY ANDY DIRECTION BY ART COLLECTIVE. YOUTH / LATINO BARRERA DESIGNS 4. JAVIER / TRE CLUB 3. TERRENCE CAMPBELL BETWEEN DESIGN IS A COLLABORATION ON IT LOGO GET DOWN 3 4 74-81 NORTH CORRIDOR/AMERICAN LEGION MALL 1-17 MASS AVE & ALABAMA ST 74 THE INDIANAPOLIS PUBLIC LIBRARY: during summertimes, people of all ages are 79 CROSSFIT NAPTOWN: FITNESS ACTIVITIES 1 INDY READS BOOks: GO NORTHEAST, 7 FAMILIES FIRST: CRAFTY FAMILIES Alabama St. between Vermont and New GET ON DOWN TO THE LIBRARY! invited to join in and jump to lively music. Offering basic level workouts, Paleo-friendly YOUNG MAN Arts, crafts, activities and family photos. York streets Decorate bookmarks and write silly or beautifully- South side of St. Clair St. bet. Pennsylvania foods and an interactive chalk wall. A mock 1860’s railroad camp, a train full of NE corner of Alabama & North streets 3:00 PM - 6:00 PM crafted poetry inspired by the Trail, PLUS: & Meridian streets, across from Library 609 N. Delaware St., at the corner of North free books, cold drinks, and miniature horses. 11:00 AM - 3:00 PM 13 DOWNTOWN YMCA: PIRATES OF THE MUCCA PAZZA 1:00 PM - 3:00 PM and Delaware streets East end of Mass. Ave., Mass. & Bellefontaine St. 8 LIVE NATION / OLD NATIONAL CENTRE: CULTURAL TRAIL! Chicago-based eccentric gang of 77 DANCE KALEIDOSCOPE: EVERY DAY WE 1:00 PM - 3:00 PM 10:00 AM - 6:00 PM FOOD TRUcks & BEER GARDEN A scavenger hunt.