Turongo: the North Island Main Trunk Railway and the Rohe Potae, 1870-2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Zealand Gazette

~umb. 37 809 NEW ZEALAND THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE Juh[isgtlt bai ~utgorit~ WELLINGTON, THURSDAY, JULY 3, 1947 Crown Land set apart for Road in Block IX, Ngongotaha Survey District, and Block XIV, Te Ati-a-1nuri Survey District [L.S.] B. C. FREYBERG, Governor-General A PROCLAMATION URSUANT to the Public Works Act, 1928, I, Lieutenant-General Sir Bernard Cyril Freyberg, the Governor-General of the Dominion P of New Zealand, do hereby proclaim and declare that the Crown land described in the Schedule hereto is hereby set apart for road; and I do also declare that this Proclamation shall take effect on and after the seventh day of July, one thousand nine hundred and forty-seven. SCHEDULE Approximate Situated in Areas of the Being Situated In Survey District Shown on Plan (',oloured Pieces of Crown Block of on Plan Land set apart. I I I A. R,, P. 4 3 2 Formerly Railway land ii{ Proclamation 9580 .. IX Ngongotaha .. P.W.D. 125605 . Red. (S.O. 29400.) 5 0 21 Part Tatua West Block in D.P. 589 .. .. XIV Te Ati-a-muri. P.W.D. 125606 .. Sepia, edge d sepia. 0 0 18·5 Part Tatua West Block in D.P. 516 .. .. XIV ,, .. .. Orange, edged (S.O. 33092.) " orange. (Auckland R.D.) In the Auckland Land District; as the same are more particularly delineated on the plans marked and coloured as above mentioned, and deposited in the office of the Minister of Works at Wellington. Given under the hand of His Excellency the Governor-General of the Dominion of New Zealand, and issued under the Seal of t~at Dominion, this 25th day of June, 1947. -

Schedule D Part3

Schedule D Table D.7: Native Fish Spawning Value in the Manawatu-Wanganui Region Management Sub-zone River/Stream Name Reference Zone From the river mouth to a point 100 metres upstream of Manawatu River the CMA boundary located at the seaward edge of Coastal Coastal Manawatu Foxton Loop at approx NZMS 260 S24:010-765 Manawatu From confluence with the Manawatu River from approx Whitebait Creek NZMS 260 S24:982-791 to Source From the river mouth to a point 100 metres upstream of Coastal the CMA boundary located at the seaward edge of the Tidal Rangitikei Rangitikei River Rangitikei boat ramp on the true left bank of the river located at approx NZMS 260 S24:009-000 From confluence with Whanganui River at approx Lower Whanganui Mateongaonga Stream NZMS 260 R22:873-434 to Kaimatira Road at approx R22:889-422 From the river mouth to a point approx 100 metres upstream of the CMA boundary located at the seaward Whanganui River edge of the Cobham Street Bridge at approx NZMS 260 R22:848-381 Lower Coastal Whanganui From confluence with Whanganui River at approx Whanganui Stream opposite Corliss NZMS 260 R22:836-374 to State Highway 3 at approx Island R22:862-370 From the stream mouth to a point 1km upstream at Omapu Stream approx NZMS 260 R22: 750-441 From confluence with Whanganui River at approx Matarawa Matarawa Stream NZMS 260 R22:858-398 to Ikitara Street at approx R22:869-409 Coastal Coastal Whangaehu River From the river mouth to approx NZMS 260 S22:915-300 Whangaehu Whangaehu From the river mouth to a point located at the Turakina Lower -

Te Awamutu Courier

ISSN 1170-1099 FOR ALL YOUR REAL ESTATE NEEDS CONTACT: Chris Gadsby Rural/Lifestyle Specialist 075TC070/06 Mobile: 027 246 5800 A/hrs: 07 870 1386 Published Tuesday and Thursday THURSDAY, JULY 6, 2006 Rosetown Realty Ltd MREINZ phone: (07) 871-7149 Circulated FREE to all households throughout Te Awamutu and surrounding districts. Extra copies 35c. BRIEFLY Shellfi sh warning Trees make way for roses includes Aotea The Public Health Unit of Paddy Stephens rapt Pat’s ‘Big Purple’ will thrive out of the shade Waikato District Health Board today issued a public health Paddy Stephens is una- tenance out of existing warning against collecting or shamedly ecstatic that budgets. consuming shellfi sh harvested several large trees have Asset manager recrea- on the West Coast between, but been removed from the tion, Max Ward says the excluding, Kawhia Harbour and Rose Garden. cashmeriana had lost a Kaipara Harbour. She is a self-confessed third of its crown due to The warning is an extension tree lover - but adds her dieback and it was agreed to one issued on June 9 to fi rst passion is for the to remove it, along with include Aotea Harbour (also roses. fi ve or six trees on the includes Raglan and Manukau Mrs Stephens is chair- Gorst Avenue boundary Harbours). person of the Te Awamutu to the Rose Garden which Routine tests on shellfi sh Rose Trust, the organi- have pushed over the samples taken from Aotea sation that has spent brick wall. Harbour last week have shown thousands of dollars over They will make way levels of Paralytic Shellfi sh 30 years stocking the Te for a new footpath and Poisoning (PSP) at 129 micro- Awamutu Rose Garden boundary fence - once grams of toxin per 100 grams with quality varieties. -

The Native Land Court, Land Titles and Crown Land Purchasing in the Rohe Potae District, 1866 ‐ 1907

Wai 898 #A79 The Native Land Court, land titles and Crown land purchasing in the Rohe Potae district, 1866 ‐ 1907 A report for the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry (Wai 898) Paul Husbands James Stuart Mitchell November 2011 ii Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Report summary .................................................................................................................................. 1 The Statements of Claim ..................................................................................................................... 3 The report and the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry .............................................................................. 5 The research questions ........................................................................................................................ 6 Relationship to other reports in the casebook ..................................................................................... 8 The Native Land Court and previous Tribunal inquiries .................................................................. 10 Sources .............................................................................................................................................. 10 The report’s chapters ......................................................................................................................... 20 Terminology ..................................................................................................................................... -

The Timber Trail Pureora - Ongarue

The Timber Trail Pureora - Ongarue A new cycling adventure The Timber Trail between Pureora and Ongarue, when fully opened, will provide 85 km of cycling pleasure through bush covered hills and across deep gorges. A 2-3 day cycling adventure on relatively easy gradients and surfaces, the Timber Trail is one of several cycle trails being developed as part of Nga Haerenga - the New Zealand Cycle Trails. e g d i Utilising historic bush tramways, old bulldozer and hauler r B roads and newly constructed track, this Grade 2 trail features u k u t 35 bridges, including 8 large suspension bridges (the longest u k u being 141 metres). It showcases the historic Ongarue Spiral t a g and passes through magnificent podocarp forests of rimu, totara, n a M miro, matai and kahikatea, as well as some exotic forestry and e th more open vegetation with extensive views of the surrounding ng ssi landscape. Most of the trail is now open with a small section to be Cro opened early in 2013. Note: The trail is grade 2 ‘easy’ for riding north to south but is grade 3-4 when ridden south to north. It is a multi-use track for cycling and walking so share with care. Getting there The Timber Trail is an easy 1-2 hr drive from Rotorua, Taupo and Hamilton. It begins at Pureora Forest off SH30 between Te Kuiti and Mangakino. The central part of the trail can be accessed from Piropiro campsite at the end of Kokomiko Road, Waimiha, and from Ongarue via SH 4 at the southern end. -

12 GEO V 1921 No 64 Waikato and King-Country Counties

604 1~21, No. 64.J Waikato and King-country Oounties. [12 GEO. V. New Zealand. Title. ANALYSIS. 1. Short Title and commencement. 10. Boundaries of Raglan County altered. 2. Act deemed to be a special Act. 11. Boundaries of Waikato County altered. 3. Otorohanga County constituted. 12. Boundaries of Piako County altered. 4. Taumarunui County constituted. 13. Boundaries of Waipa County altered. 5. Application of Counties Act, 1920. 14. Taupo East and Taupo West Counties united. 6. Awakino and Waitomo Counties abolished, and 15. Road districts abolished. Waitomo County constituted. 16. Taupo Road District constituted. 7. Antecedent liabilities of Awakino and Wal 17. Application of provisions of Counties Act, 1920, tomo County C,ouncils to be antecedent in respect of alterations of boundaries. liability of new Waitomo County. 18. Temporary provision for control of certain 8. System ,of rating in Waitomo County. districts. 9. Boundaries of Kawhia County altered. Schedules. 1921-22, No. 64 . Title .AN ACT to give Effect to the Report of the Commission appointed under Section Ninety-one of the Reserves and other Lands Disposal and Public Bodies Empowering Act, 1920. [11th February, 1922. BE IT ENACTED by the General Assembly of New Zealand in Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows :- Short Title and 1. This Act may be cited as the Waikato and King-country commencement. Counties Act, 1921-22, and shall come into operation on the :o/st day of April, nineteen hundred and twenty-two. Act deemed to be a 2. This Act shall be deemed to be a special Act within the special Act. -

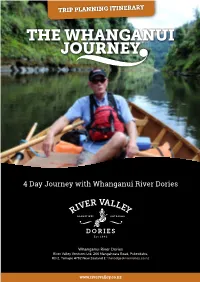

The Whanganui Journey the Whanganui Journey

TRIP PLANNING ITINERARY THE WHANGANUI JOURNEY THE WHANGANUI JOURNEY 4 Day Journey with Whanganui River Dories Whanganui River Dories River Valley Ventures Ltd, 266 Mangahoata Road, Pukeokahu, RD 2, Taihape 4792 New Zealand E: [email protected] www.rivervalley.co.nz TRIP PLANNING ITINERARY THE WHANGANUI JOURNEY Thanks for Choosing Whanganui River Dories! About Whanganui River Dories Whanganui River Dories is a part of River Valley Ventures Ltd. Since 1982, family owned and Taihape based adventure company, River Valley, has been offering trips on the rivers of the central North Island of New Zealand. Based from River Valley Lodge, the company offers raft and inflatable kayak adventures on the Rangitikei and Ngaru- roro Rivers, and through Whanganui River Dories, dory trips on the Whanganui River through the Whanganui National Park. We offer river trips that vary in duration from 1/2 day to 6 days. Part of the experiences River Valley also offers are horse treks with River Valley Stables. These treks, from a half day out to 7 days, explore central North Island high country. A point of difference for River Valley Stables is the emphasis on a learning experience using Natural Horse Training as well as the ride itself. River Valley is a company that is also heavily involved in “giving back.” We do this through our Stoat trapping program that is centred around the Rangitikei River at Pukeokahu near Taihape. The aim of this program is to protect and grow the threat- ened native bird population. Thanks for choosing River Valley for your trip. We look forward to being on the river with you. -

Mokau River and Tributaries Draining the Mokau Coalfield

lssN o1 13-2504 New Zealand Freshwater Fisheries Report No . 110 Fish and fisheries values of the Mokau River and tributaries draining the Mokau coalfield ï¡;t. 'Ll:..".! tiH::::: i'.,....'.'....'....' MAFFish New Zealand freshwater fisheries report no. 110 (1989) New Zeal and Freshwater Fjsheries Report No. 110 Fish and fisheries values of the Mokau Ri ver and tributarjes dra'inìng the Mokau coalfjeld by S.M. Hanchet J.t^l. Hayes Report to : N. Z. Coal CorPorat'ion Freshwater Fisheries Centre MAFFISH Rotoru a June 1989 New Zealand freshwater fisheries report no. 110 (1989) NEt^l ZEALAND FRESHWATER FISHERIES REPORTS This report is one of a series issued by the Freshwater Fjsherjes Centre, MAFF'ish, on issues related to New Zealand's freshwater fisheries. They are'issued under the following criteria: (1) They are for limited circulatjon, so that persons and orgàn.isations norma'l1y receiving MAFFìsh publications shóuld not expect to receive copíes automaticalìy. Q) Copies wiì'l be'issued free on'ly to organisations to whjch the report is djrect'ly relevant. They wjlì be jssued to other organ'i sati ons on request. (3) A schedule of charges is jncluded at the back of each report. Reports from N0.95 onwards are priced at a new rate whìch includes packaging and postage, but not GST. Prices for Reports Nos. t-g+- conti nue to j ncl ude packagj ng, _postage, and GST. In the event of these reports go'ing out of pfiint, they wìll be reprinted and charged for at the new rate. (4) Organisations may apply to the librarian to be put 91 the malling lìst to recejve alì reports as they are published. -

LOWER NORTH ISLAND LONGER-DISTANCE ROLLING STOCK BUSINESS CASE PREPARED for GREATER WELLINGTON REGIONAL COUNCIL 2 December 2019

LOWER NORTH ISLAND LONGER-DISTANCE ROLLING STOCK BUSINESS CASE PREPARED FOR GREATER WELLINGTON REGIONAL COUNCIL 2 December 2019 This document has been prepared for the benefit of Greater Wellington Regional Council. No liability is accepted by this company or any employee or sub-consultant of this company with respect to its use by any other person. This disclaimer shall apply notwithstanding that the report may be made available to other persons for an application for permission or approval to fulfil a legal requirement. QUALITY STATEMENT PROJECT MANAGER PROJECT TECHNICAL LEAD Doug Weir Doug Weir PREPARED BY Doug Weir, Andrew Liese CHECKED BY Jamie Whittaker, Doug Weir, Deepa Seares REVIEWED BY Jamie Whittaker, Phil Peet APPROVED FOR ISSUE BY Doug Weir WELLINGTON Level 13, 80 The Terrace, Wellington 6011 PO Box 13-052, Armagh, Christchurch 8141 TEL +64 4 381 6700 REVISION SCHEDULE Authorisation Rev Date Description No. Prepared Checked Reviewed Approved by by by by 1 27/07/18 First Draft Final DW, AL JW JW DW 2 24/10/18 Updated First Draft Final DW JW JW DW Revised Draft Final (GWRC 3 05/08/19 DW DW PP DW Sustainable Transport Committee) 3 20/08/19 Updated Revised Draft Final DW DS PP DW Amended Draft Final 4 26/09/19 DW DW PP DW (GWRC Council) 5 02/12/19 Final DW DW PP DW Stantec │ Lower North Island Longer-Distance Rolling Stock Business Case │ 2 December 2019 Status: Final │ Project No.: 310200204 │ Our ref: 310200204 191202 Lower North Island Longer-Distance Rolling Stock Busines Case - Final.docx Executive Summary Introduction This business case has been prepared by Stantec New Zealand and Greater Wellington Regional Council (GWRC), with input from key stakeholders including KiwiRail, Transdev, Horizons Regional Council and the NZ Transport Agency (NZTA), and economic peer review by Transport Futures Limited. -

Attachment 1 Wellington Regional Rail Strategic Direction 2020.Pdf

WELLINGTON REGIONAL RAIL STRATEGIC DIRECTION 2020 Where we’ve come from Rail has been a key component of the Wellington Region’s transport network for more than 150 years. The first rail line was built in the 1870s between Wellington and Wairarapa. What is now known as the North Island Main Trunk followed in the 1880s, providing a more direct route to Manawatū and the north. Two branch lines were later added. The region has grown around the rail network, as villages have turned into towns and cities. Much of it was actively built around rail as transit-oriented development. Rail has become an increasingly important way for people to move about, particularly to Wellington’s CBD, and services and infrastructure have been continuously expanded and improved to serve an ever-growing population. The region is a leader in per capita use of public transport. Wellington Region Rail Timeline 1874 1927 1954 1982 2010 2021 First section of railway between Hutt line deviation opened as a branch Hutt line deviation to Manor EM class electric FP ‘Matangi’ class Expected Wellington and Petone between Petone and Waterloo Park, creating Melling line multiple units electric multiple completion 1955 introduced units introduced of Hutt line 1876 1935 Hutt line duplication to Trentham duplication, Hutt line to Upper Hutt Kāpiti line deviation to Tawa, creating 1983 and electrification to Upper Hutt 2011 Trentham to 1880 Johnsonville line Kāpiti line Rimutaka Tunnel and deviation Upper Hutt 1 Wairarapa line to Masterton 1 electrification Kāpiti line 2 1938 replace -

Portraits of Te Rangihaeata

PART IV MR59 103 PART IV MR01 Cootia Pipi Kutia the portrait of cootia at Pitt Rivers Keats’s poem: “Rauparaha stayed on board to dinner, Museum is the first in the Coates sketchbook, and her with his wife, a tall Meg Merrilies-like woman, who husband, Te Rauparaha, is the second. Cootia is more had a bushy head of hair, frizzled out to the height of six commonly known as Kutia or Pipi Kutia. inches all round, and a masculine voice and appetite. Pipi Kutia was wife of Te Rauparaha (MR02), She is the daughter of his last wife by a former husband.”3 acknowledged fighting chief of Ngāti Toa, and of the Tainui–Taranaki alliance. Her mother, Te The New Zealand Company surveyor John Barnicoat Akau, was high-born of the Te Arawa tribe (of the described members of Te Rauparaha’s party in Nelson in Rotorua district of the central North Island of New March 1843: “He has brought three of his wives with him ... Zealand), and her father, Hapekituarangi, was a senior the second ... is a tall stout woman of handsome features hereditary chief of Ngāti Raukawa of Maungatautari if not too masculine ...”4 And the Australian artist (the present-day Cambridge district). Hapekituarangi G. F. Angas, who toured New Zealand in mid to late 1844, was a distant kinsman of Te Rauparaha. On his was also impressed, describing Kutia: deathbed, Hape’s mantle of seniority bypassed his “Rauparaha’s wife is an exceedingly stout woman, and own sons and fell to Te Rauparaha, and in accordance wears her hair, which is very stiff and wiry, combed up with custom, Te Rauparaha married Hape’s widow, into an erect mass upon her head, about a foot in height, Te Akau.1 In c. -

Te Awamutu Courier Thursday, October 15, 2020 Firefighter’S 50 Years Marked

Te Awamutu Next to Te Awamutu The Hire Centre Te Awamutu Landscape Lane, Te Awamutu YourC community newspaper for over 100 years Thursday, October 15, 2020 0800 TA Hire | www.hirecentreta.co.nz BRIEFLY Our face on show The Our Face of 2020 Art Exhibition is being held at the Te Awamutu i-Site Centre Burchell Pavilion this weekend. The exhibition features works from local Rosebank artists and is open daily from 10am- 4pm, Friday — Sunday, October 16 — 18. Pirongia medical clinic resumes Mahoe Medical Centre’s weekly satellite clinic at Pirongia with Dr Fraser Hodgson will re-commence this month from Thursday, October 29. Clinics are at St Saviour's Church, phone 872 0923 for an appointment. In family footsteps Robyn and Dean Taylor live and work locally, but they have wide horizons which they fully explore. Hear them talk about a recent visit to South Africa at the Continuing Education Group’s meeting on Wednesday, Rob Peters presents Murry Gillard with a life member’s gift. Photos / Supplied October 21 in the Waipa¯ Workingmen’s Club. See details in classified section or phone 871 6434 or 870 3223. Housie fundraiser Rosetown Lions Club is 50 years of service holding a fundraising afternoon this Saturday with proceeds supporting youth in our community. Te Awamutu firefighter Murry Gillard made a life member after first joining in 1970 The Housie Afternoon takes place at Te Awamutu RSA fter Covid-19 forced the brigade’s 1934 Fordson V8 appliance The official party was made up of averaged 97 per cent in the 50 years.