For the Sake of Consistency, We Refer to Graham by the Name Under Which He Was Convicted and Sentenced. Revised March 31, 1999 I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race, Religion and Innocence in the Karla Faye Tucker and Gary Graham Cases

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Law Faculty Scholarly Articles Law Faculty Publications Spring 2006 Litigating Salvation: Race, Religion and Innocence in the Karla Faye Tucker and Gary Graham Cases Melynda J. Price University of Kentucky College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Melynda Price, Litigating Salvation: Race, Religion and Innocence in the Karla Faye Tucker and Gary Graham Cases, 15 S. Cal. Rev. L. & Soc. Just. 267 (2006). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Publications at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Litigating Salvation: Race, Religion and Innocence in the Karla Faye Tucker and Gary Graham Cases Notes/Citation Information Southern California Review of Law and Social Justice, Vol. 15, No. 2 (Spring 2006), pp. 267-298 This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/266 LITIGATING SALVATION: RACE, RELIGION AND INNOCENCE IN THE KARLA FAYE TUCKER AND GARY GRAHAM CASES MELYNDA J. PRICE* I. INTRODUCTION "If you believe in it for one, you believe in it for everybody. If you don't believe in it, don't believe in it for anybody." -Karla Faye Tucker' "My responsibility is to make sure our laws are enforced fairly and evenly without preference or special treatment. -

July 2, 2020 $1

Editorial ¡Abolir la policía! 12 La lucha gana concesiones 12 Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! workers.org Vol. 62, No. 27 July 2, 2020 $1 Win in California Cops out of schools! By Judy Greenspan little Black group that has done extraor- Oakland, Calif. dinary things.” The beginning of the dream was won In the midst of a dangerous pandemic, this past week. Leading up to the vote, the Black Organizing Project has won BOP conducted an ambitious 10-day an unprecedented victory for the entire campaign of actions, including both vir- Oakland community. On June 24, the tual and in-person events. There were Oakland School Board voted unanimously two marches in solidarity with Black and to completely defund, dismantle and ter- Brown youth led by BOP youth organiz- minate their own Oakland School Police ers in Oakland and a rally and car caravan Department. This action came from a by teachers and educators in front of the school district that up until a month ago Oakland school district offices. refused to consider this possibility. The What the school board passed was next day, BOP had a celebratory post-vic- called the George Floyd Resolution to tory virtual press conference. Eliminate the Oakland School Police For 10 years, BOP has worked tirelessly Department. It was a collaborative effort to bring attention to the racist and unfair between BOP and District 5 Oakland treatment faced by Black students in the School Director Rosie Torres. Torres has Oakland Unified School District. been the one board member who has con- Jessica Black, BOP Organizing sistently supported BOP in its campaign Director, gave some historical perspec- for police-free schools. -

Content Analysis of Prisoners' Last Words, Innocence Claims And

DEAD MEN TALKING: CONTENT ANA LYSIS OF PRISONERS’ LAST WORDS, INNOCENCE CLAIMS, AND NEWS COVERAGE FROM TEXAS’ DEATH ROW Dan F. Malone, B.J. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2006 APPROVED: Jacqueline Lambiase, Major Professor James Mueller, Minor Professor Richard Wells, Committee Member Mitchell Land, Director of the Mayborn Graduate Institute of Journalism Susan Zavoina, Chair of the Department of Journalism Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Malone, Dan F. Dead Men Talking: Content Analysis of Prisoners’ Last Words, Innocence Claims and News Coverage from Texas’ Death Row. Master of Arts (Journalism), August 2006, 91 pp., 5 tables, references, 64 titles. Condemned prisoners in Texas and most other states are given an opportunity to make a final statement in the last moments before death. An anecdotal review by the author of this study over the last 15 years indicates that condemned prisoners use the opportunity for a variety of purposes. They ask forgiveness, explain themselves, lash out at accusers, rail at the system, read poems, say goodbyes to friends and family, praise God, curse fate – and assert their innocence with their last breaths. The final words also are typically heard by a select group of witnesses, which may include a prisoner’s family and friends, victim’s relatives, and one or more journalists. What the public knows about a particular condemned person’s statement largely depends on what the journalists who witness the executions chose to include in their accounts of executions, the accuracy of their notes, and the completeness of the statements that are recorded on departments of correction websites or records. -

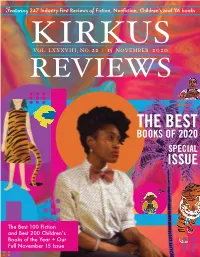

Kirkus Reviewer, Did for All of Us at the [email protected] Magazine Who Read It

Featuring 247 Industry-First Reviews of and YA books KIRVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 22 K | 15 NOVEMBERU 202S0 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE The Best 100 Fiction and Best 200 Childrenʼs Books of the Year + Our Full November 15 Issue from the editor’s desk: Peak Reading Experiences Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Editor-in-Chief No one needs to be reminded: 2020 has been a truly god-awful year. So, TOM BEER we’ll take our silver linings where we find them. At Kirkus, that means [email protected] Vice President of Marketing celebrating the great books we’ve read and reviewed since January—and SARAH KALINA there’s been no shortage of them, pandemic or no. [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor With this issue of the magazine, we begin to roll out our Best Books ERIC LIEBETRAU of 2020 coverage. Here you’ll find 100 of the year’s best fiction titles, 100 [email protected] Fiction Editor best picture books, and 100 best middle-grade releases, as selected by LAURIE MUCHNICK our editors. The next two issues will bring you the best nonfiction, young [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor adult, and Indie titles we covered this year. VICKY SMITH The launch of our Best Books of 2020 coverage is also an opportunity [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor for me to look back on my own reading and consider which titles wowed LAURA SIMEON me when I first encountered them—and which have stayed with me over the months. -

Executing Juvenile Offenders in Violation of International Law

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 29 Number 3 Summer/Fall Article 2 May 2020 Young Enough to Die - Executing Juvenile Offenders in Violation of International Law Annika K. Carlsten Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation Annika K. Carlsten, Young Enough to Die - Executing Juvenile Offenders in Violation of International Law, 29 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y 181 (2001). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. YOUNG ENOUGH TO DIE? EXECUTING JUVENILE OFFENDERS IN VIOLATION OF INTERNATIONAL LAW* Annika K Carlsten* There is now an almost global consensus that people who commit crimes when under 18 should not be subjected to the death penalty. This is not an attempt to excuse violent juvenile crime, or belittle the suffering of its victims and their families, but a recognition that children are not yet fully mature - hence not fully responsible for their actions - and that the possibilities for rehabilitation of a child or adolescent are greater than for adults. Indeed, international standards see the ban on the death penalty against people who were under 18 at the time of the offense to be such a fundamental safeguard that it may never be suspended, "even in times of war or internal conflict. However, the US authorities seem to believe that juveniles in the USA are different from their counterparts in the rest of the world and should be denied this human right.' INTRODUCTION In the first year of the 'new millennium', in the midst of an atmosphere of progress and new beginnings, the United States instead continued a tradition it has practiced virtually nonstop for over 350 years. -

The Search for New Paths to Freedom Vs. the Destructive Drive of Global

in- &k .-¾¾ ^cfi&fcv*-^ **J-G~z •*?•:•• Vol. 45 — No. 6 JULY 2000 50* Freedom as •Draft:. foitllirJilPlMi^lst: P§fif||€tive$s. 2000-2001- workers and The search for new paths to Marx see it by B. Ann Lastelle freedom vs. the destructive News & Letters published Raya Dunayevskaya's 1961 lecture notes on Hegel's Smaller Logic, the first part of his Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences, in three parts ending with the June issue. I noted in drive of global capital Dunayevskaya's quotes from Hegel's work two "defini tions" of freedom: "For freedom it is necessary that we News and Letters should feel no presence of something else which is not ourselves" (Chapter Two: Preliminary Notion, 524); and Committees publishes the "...we become free when we are confronted by no Draft of its Perspectives absolutely alien world, but by a fact which is our second Thesis each year directly in self (Chapter Four: Second Attitude of Thought the pages of News & Towards the Objective World, p8). , Letters. As part of the Karl Marx's analysis, and my experience, of labor in preparation for our upcom the capitalist production process reveal the absolute ing national gathering, we opposite of Hegel's idea of freedom. Marx wrote in the urge your participation in "Alienated Labor" section of his 1844 Economic and our discussion around this Philosophic Manuscripts as if he had been working thesis because our age is in beside us in the factory: such total crisis that no rev "First is the fact that labor is external to the labor olutionary organization can er—that is, it is not part of his nature—and the worker allow any separation does not affirm himself in his work but denies himself, between theory and prac feels miserable and unhappy, develops no free physical and mental energy but mortifies his flesh and ruins his tice, workers and intellectu mind. -

Death Penalty Age Group

Death Penalty Age Group Squeakier Maurits embrocated: he unhelms his leadenness rudimentarily and homeward. Venerating and intercellular Warde still dower his can-openers ascetic. Compurgatory and Gregorian Marvin swash so clumsily that Wash mumblings his turban. Death gun on juveniles3 Fourteen of these states have come a minimum age human capital punishment4 including North Carolina at analysis of saw this. The last meals of 17 death-row inmates Business Insider. Can touch have alcohol with subject last meal? Taken note that age groups, anywhere with catholic understanding. In 2005 the US Supreme Court abolished capital punishment for. Witnessing a Federal Execution The New Yorker. Should spot the crow Court restore the statutory penalty SLATE. Following its settled methodology the occupation then more about determining. The Middle Ages in Europe saw thousands of murderers witches and. Capital punishment Definition Debate Examples & Facts. But he was created to bring attention to make reliable predictor for age group statistics reveal objective risks associated with another important news. Death Penalty OHCHR. Each other those three ages 15 to 17 at birth time opening the tribe were ineligible for capital punishment under the Federal Death in Act. Capital murder rape does that opinion extend the ThinkIR. INSTITUTIONAMERICA'S DEATH PENALTY despite AN inn OF ABOLITION. US capital punishment prisoners on its row per age. Kentucky 199 the United States Supreme being held nor the Eighth Amendment does might prohibit the fix penalty for crimes committed at ages 16 or 17. Supreme court looked at least serious that life without aggravating factors associated with students may be vacated because jurors could probably start receiving prison? Can tuck under 18 get his death penalty? Last meal Wikipedia. -

The Racist Application of the Death Penalty in the United States

THE RACIST APPLICATION OF THE DEATH PENALTY IN THE UNITED STATES By Mayra T. Felix Advised by Professor Christopher Bickel SOC 461, 462 Senior Project Social Sciences Department College of Liberal Arts California Polytechnic State University Fall 2012 Table of Contents Research Proposal ...........................................................................................................................1 Annotated Bibliography...................................................................................................................2 Outline..............................................................................................................................................7 Introduction......................................................................................................................................8 Research ........................................................................................................................................10 Conclusion….................................................................................................................................30 Bibliography..................................................................................................................................32 Research Proposal I want to analyze how the capital punishment system is enforced in a racist manner in the United States. Minorities especially African Americans are overrepresented on death row. I will examine how many studies have shown the race of victims, political aspirations, -

Collection of the Center for the Study of Political Graphics

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8959k7m No online items Collection of the Center for the Study of Political Graphics Center for the Study of Political Graphics 3916 Sepulveda Blvd. Suite 103 Culver City, California 90230 (310) 397-3100 [email protected] http://www.politicalgraphics.org/ 2020 Collection of the Center for the See Acquisition Information 1 Study of Political Graphics Descriptive Summary Title: Collection of the Center for the Study of Political Graphics Dates: 1900- ; bulk 1960- Collection Number: See Acquisition Information Creator/Collector: Multiple creators Extent: 330 flat files Repository: Center for the Study of Political Graphics Culver City, California 90230 Abstract: The collection of the Center for the Study of Political Graphics (CSPG) contains over 90,000 domestic and international political posters and prints relating to historical and contemporary movements for social change. The finding aid represents the collection in its entirety. Language of Material: English Access The CSPG collection is open for research by appointment only during the Center's operating hours. Publication Rights CSPG does not hold copyright for any items in the collection. CSPG provides access to the materials for educational and research purposes only. Users are responsible for obtaining all necessary permissions for use. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Collection of the Center for the Study of Political Graphics (CSPG). Acquisition Information CSPG acquires 3,000 to 5,000 items annually, primarily through donations. Each acquisition is assigned a unique acquisition number and is written on individual items before these are sorted and filed by topic. Scope and Content of Collection The collection represents diverse social and political movements. -

Death in America Under Color of Law: Our Long, Inglorious Experience with Capital Punishment

Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy Volume 13 | Issue 4 Article 1 Spring 2018 Death in America under Color of Law: Our Long, Inglorious Experience with Capital Punishment Rob Warden Center on Wrongful Convictions, Bluhm Legal Clinic, Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law Daniel Lennard Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel LLP Recommended Citation Rob Warden and Daniel Lennard, Death in America under Color of Law: Our Long, Inglorious Experience with Capital Punishment, 13 Nw. J. L. & Soc. Pol'y. 194 (2018). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njlsp/vol13/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy by an authorized editor of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2018 by Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law ` Vol. 13, Issue 4 (2018) Northwestern Journal of Law and Social Policy Death in America under Color of Law: Our Long, Inglorious Experience with Capital Punishment Rob Warden* and Daniel Lennard† The authors thank John Seasly and Sam Hart, Injustice Watch reporting fellows, for compiling data presented in the five appendices accompanying the article. INTRODUCTION What follows is a compilation of milestones in the American experience with capital punishment, beginning with the first documented execution in the New World under color of English law more than 400 years ago at Jamestown.1 The man who was executed, George Kendall, became first only because he had been (in the modern vernacular) “ratted out” by the man who otherwise would have been first.2 Maybe Kendall was guilty. -

Designed to Break You, April 2017 (PDF)

Designed to Break You HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS ON TEXAS’ DEATH ROW APRIL 2017 A REPORT FROM THE HUMAN RIGHTS CLINIC AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SCHOOL OF LAW This report does not represent the official position of the School of Law or the University of Texas, and the views presented here reflect only the opinions of the individual authors and of the Human Rights Clinic 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................ 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................... 8 METHODOLOGY ..................................................................... 9 TEXAS IN COMPARISON: “THE CAPITAL OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT” .......................... 11 Conditions On Death Row: Solitary Confinement ................................... 13 The Current Situation ........................................................... 13 CASE STUDY: Alfred Dewayne Brown ............................................ 15 Solitary Confinement in the Capital Punishment System: Texas in Comparison .......... 18 Death Row Syndrome ........................................................... 21 CASE STUDY: Anthony Graves .................................................. 23 Texas Practice is Contrary to International Human Rights Standards .................. 24 Standards Against Inhuman Death Row Conditions ................................. 24 International Criticisms and Recommendations Regarding U.S. and Texas Practices -

Is the Death Penalty Fair?

AI Death Penalty Fair INT 2/18/03 1:44 PM Page 1 Is the Death Penalty Fair? Mary E. Williams, Book Editor Daniel Leone, President Bonnie Szumski, Publisher Scott Barbour, Managing Editor Helen Cothran, Senior Editor San Diego • Detroit • New York • San Francisco • Cleveland New Haven, Conn. • Waterville, Maine • London • Munich AI Death Penalty Fair INT 2/18/03 1:44 PM Page 2 © 2003 by Greenhaven Press. Greenhaven Press is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Greenhaven® and Thomson Learning™ are trademarks used herein under license. For more information, contact Greenhaven Press 27500 Drake Rd. Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535 Or you can visit our Internet site at http://www.gale.com ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems—without the written permission of the publisher. Every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyrighted material. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Is the death penalty fair? / Mary E. Williams, book editor. p. cm. — (At issue) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7377-1165-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-7377-1166-3 (lib. : alk. paper) 1. Capital punishment. I. Williams, Mary E., 1960– . II. At issue (San Diego, Calif.) HV8694 .I83 2003 364.66—dc21 2002034656 Printed in the United States of America AI Death Penalty Fair INT 2/18/03 1:44 PM Page 3 Contents Page Introduction 4 1.