Who Is My Brother? an Ironic Reading of Genesis 19:1-111

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The State Independent Electoral Commissions in Nigeria: a Study of Bauchi, Edo, Imo, Kaduna, Lagos and Plateau States

The State Independent Electoral Commissions in Nigeria: A Study of Bauchi, Edo, Imo, Kaduna, Lagos and Plateau States Edited by Massoud Omar 0 Contributors Musa Abutudu Associate Professor, Department of Political Science. University of Benin. Edo State, Nigeria. Chijioke K. Iwuamadi Research Fellow, Institute for Development Studies University of Nigeria. Enugu State, Nigeria. Massoud Omar Department of Local Government Studies Ahmadu Bello University. Zaria, Kaduna State. F. Adeleke Faculty of Law, Lagos State University. Lagos State, Nigeria. Habu Galadima Department of Political Science, Bayero University, P.M.B. 3011, Kano-Nigeria Dung Pam Sha Department of Political Science, 1 University of Jos. Plateau State. 2 Table of Contents Introduction 4-10 Chapter I Bauchi State Independent Electoral Commission Habu Galadima and Aisha Omar 7-61 Chapter II The Edo State Independent Electoral Commission Musa Abutudu 62-97 Chapter III The Imo State Independent Electoral Commission (SIEC) Chijioke K. Iwuamadi 98- 135 Chapter IV The Kaduna State Independent Electoral Commission Massoud Omar 136-159 Chapter V Lagos State State Independent Electoral Commission in F.A.R Adeleke 156-191 Chapter VI The Plateau State Independent Electoral Commission: Dung Pam Sha 192-240 Conclusion 241-242 3 List of Tables and Figures Table 1.1 State of Residence Table 1.2 Local Government Area Table 1.3 Gender Table 1.4 Age Table 1.5 Marital Status Table 1.6 Occupation Table 1.7 Awareness of SIEC’s conduct of Local Government Elections Table 1.8 Number of times Respondents -

A Study of Violence-Related Deaths in Nafada Local Government Area Of

# Makai DANIEL http://www.ifra-nigeria.org/IMG/pdf/violence-related-deaths-gombe-jigawa-state-nigeria.pdf A Study of Violence-Related Deaths in Nafada Local Government Area of Gombe State and Auyo, Gagarawa, Gumel, Gwiwa, Kaugama and Yankwasi Local Government Areas of Jigawa State (2006-2014) IFRA-Nigeria working papers series, n°46 20/01/2015 The ‘Invisible Violence’ Project Based in the premises of the French Institute for Research in Africa on the campus of the University of Ibadan, Nigeria Watch is a database project that has monitored fatal incidents and human security in Nigeria since 1 June 2006. The database compiles violent deaths on a daily basis, including fatalities resulting from accidents. It relies on a thorough reading of the Nigerian press (15 dailies & weeklies) and reports from human rights organisations. The two main objectives are to identify dangerous areas and assess the evolution of violence in the country. However, violence is not always reported by the media, especially in remote rural areas that are difficult to access. Hence, in the last 8 years, Nigeria Watch has not recorded any report of fatal incidents in some of the 774 Local Government Areas (LGAs) of the Nigerian Federation. There are two possibilities: either these places were very peaceful, or they were not covered by the media. This series of surveys thus investigates ‘invisible’ violence. By 1 November 2014, there were still 23 LGAs with no report of fatal incidents in the Nigeria Watch database: Udung Uko and Urue-Offong/Oruko (Akwa Ibom), Kwaya Kusar (Borno), Nafada (Gombe), Auyo, Gagarawa, Kaugama and Yankwashi (Jigawa), Ingawa and Matazu (Katsina), Sakaba (Kebbi), Bassa, Igalamela- Odolu and Mopa-Muro (Kogi), Toto (Nassarawa), Ifedayo (Osun), Gudu and Gwadabaw (Sokoto), Ussa (Taraba), and Karasuwa, Machina, Nguru and Yunusari (Yobe). -

The Application of Geospatial Analytical Techniques in The

Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective Volume 10 Article 9 Number 2 Sustainable Livelihoods and Conflict March 2016 The Application of Geospatial Analytical Techniques in the Assessment of Land Use Conflicts Among Farmers and Cross-Boundary Nomadic Cattle eH rders in the Gombe Region, Nigeria Whanda J. Shittu Gombe State University, Nigeria, [email protected] Mala Galtima Gombe State University, Nigeria, [email protected] Dan Yakubu Gombe State University, Nigeria, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi Part of the African History Commons, African Studies Commons, Agricultural and Resource Economics Commons, Growth and Development Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, and the Political Economy Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Shittu, Whanda J.; Galtima, Mala; and Yakubu, Dan (2016) "The Application of Geospatial Analytical Techniques in the Assessment of Land Use Conflicts Among Farmers and Cross-Boundary Nomadic Cattle eH rders in the Gombe Region, Nigeria," Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective: Vol. 10 : No. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi/vol10/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. -

Gombe State Health Facility Listing

Gombe State Health Facility Listing LGA WARD Name of Health facility Facility Type OWNERSHIP (PUBLIC/ PRIVATE) CODE LGA State facility NO facility Ownership facility Type facility Akko Health clinic Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0001 Bula Dispensary Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0002 Bula Maternity Clinic Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0003 Akko Gamadadi Dispensary Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0004 Lawanti Dispensary Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0005 Wurodole Dispensary Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0006 Zongomari Dispensary Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0007 Arfa Medical Centre Secondary Private 16 01 2 2 0008 Bogo Maternity Clinic Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0009 Garko Dispensary Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0010 Kudulum Dispensary Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0011 Garko Gaskiya Medical Clinic Primary Private 16 01 1 2 0012 Ponon Medical Clinic Primary Private 16 01 1 2 0013 Dikko Clinic Primary Private 16 01 1 2 0014 Tabra Maternity Clinic Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0015 Tumpure Dispensary Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0016 Chilo Dispensary Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0017 Chilo Maternity Clinic Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0018 Kalshingi Gujuba Dispensary Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0019 Kalshingi Dispensary Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0020 Kalshingi (PHC) Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0021 Dongol Dispensary Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0022 Kaltanga Dispensary Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0023 Kashere Maternity Clinic Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0024 Kashere Kashere Health Centre Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0025 Kashere General Hospital Secondary Public 16 01 2 1 0026 Mispha Mat Home Primary Private 16 01 1 2 0027 Kembu Dispensary Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0028 Kidda Dispensary Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0029 Kembu Dispensary Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0030 Kumo - East Panda Maternity Clinic Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0031 Pandaya Dispensary Primary Public 16 01 1 1 0032 Tambie/Yolo Disp. -

The Syntax of Po Tangle Numerals

Mary Chimaobi Amaechi 35 Journal of Universal Language 15-2 September 2014, 35-54 The Syntax of Po Tangle Numerals 1 Mary Chimaobi Amaechi University of Ilorin, Nigeria Abstract This paper examines the endangered numerals of Po Tangle [taŋglɛ], a minority language spoken in four local government areas in Gombe State, north eastern Nigeria. The emphasis is on the cardinal whole numbers. The study explores the structure of complex numerals which are derived from simple lexical ones using syntactic coordination and complementation. The study adopts the packing strategy framework of Hurford (1975, 1987, 2003, 2007). This framework adopted applies very widely to numeral systems that uses syntactic constructions to signal multiplication and addition. It is found out that there is no overt marker for multiplicative arithmetic operation but there are two distinct markers for additive arithmetic operation, salai and ka, while the former is used for lower complex numerals in the base of ten, the latter is found in higher complex numerals of bases hundred and thousand. Keywords: Po Tangle, numeral, packing strategy, syntax, connectives, phrase structure rules Mary Chimaobi Amaechi Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages, University of Ilorin P.M.B. 1515, Ilorin, Nigeria Phone: +2348066392599; Email: [email protected] Received June 12, 2014; Revised July 30, 2014; Accepted August 28, 2014. 36 The Syntax of Po Tangle Numerals 1. Introduction In everyday life, human beings use numbers to make reference to time, quantity, distance, weight, height, and so on. It is the case that the numeral systems of most of the world’s languages are more endangered than the languages themselves. -

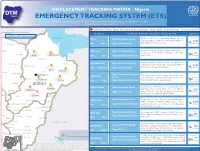

ETS) IOM OIM the DTM Emergency Tracking Tool (ETS) Is Deployed to Track and Provide Up-To-Date Information on Sudden Displacement and Return Movements

DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX - Nigeria DTM Nigeria EMERGENCY TRACKING SYSTEM (ETS) IOM OIM The DTM Emergency Tracking Tool (ETS) is deployed to track and provide up-to-date information on sudden displacement and return movements CHAD SNAPSHOT: Pulka, Bama, Monguno, Gubio, Konduga, Dikwa, Mafa, Chibok, Gwoza - February 10, 2017 NIGER Checkpoint Characteristic of movement (January 27 - February 10, 2017) Population LOCATIONS WITH IDP MOVEMENT Lake chad Estimate PULKA Type of movement: Arrivals Inow of IDPs from neighboring villages due to ongoing military activity in nearby Ngoshi village in 3,000 Gwoza LGA . Shelters are needed. persons Yunusari LGA: Gwoza Trigger: military activity Estimate Bursari BAMA Town Type of movement: Arrivals A total of 67 People returned to Nigeria from cameroon on January 29 (19 IDPs) & February 2 (48 IDPs) 67 Geidam Gubio Monguno LGA: Bama Trigger: Newly accessible areas respectively. persons Nganzai Estimate MONGUNO Town Type of movement: Arrivals Ongoing military oensive in Marte has opened up Tarmua Ngala villages previously inaccessible causing daily inux of Magumeri 8,000 LGA: Monguno Trigger: military activity IDPs towards Monguno from Marte. persons Mafa Jere Dikwa Fune Damaturu Maiduguri Type of movement: Anticipated Estimate GUBIO Town The military announced last week that people could Potiskum returns start returning to Ngetra, Kingowa, Feto, Zowo and Returns Kaga are Konduga Bama LGA: Gubio Trigger: Newly accessible areas Ardimin Wards. Returns are anticipated. anticipated Gujba Fika BORNO Estimate KONDUGA Town Type of movement: Arrivals Galtimari area of Konduga has received about 1,200 Gwoza individuals from Kawuri Village from the 27th of Damboa 1,827 Nafada Gulani LGA: Konduga Trigger: military activity January till date. -

A Wet Season Survey of Animal Trypanosomosis in Shongom Local Government Area of Gombe State. Nigeria

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Obihiro University of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine Academic Repository A wet season survey of animal trypanosomosis in Shongom local government area of Gombe state. Nigeria 著者(英) Shamaki B.U, Obaloto O.B, Kalejaiye J.O, Lawani F.A.G, Balak G.G, Charles D journal or The journal of protozoology research publication title volume 19 number 2 page range 1-6 year 2009-12 URL http://id.nii.ac.jp/1588/00001449/ J. Protozool. Res. 19, 1-6 (2009) Copyright 2008, National Research Center for Protozoan Diseases A wet season survey of animal trypanosomosis in Shongom local government area of Gombe state. Nigeria Shamaki, B.U.1*, Obaloto, O.B.1, Kalejaiye, J.O.1, Lawani, F.A.G.2, Balak, G.G.1 and Charles D.1 1Nigerian Institute for Trypanosomiasis and Onchocerciasis Research (NITOR) Vom., 2NITOR, Kaduna, Nigeria *Corresponding author: Dr. Shamaki Bala Usman,E-mail: [email protected]. ABSTRACT Two hundred and three (203) blood samples were collected from randomly selected herd comprising; cattle, 68 (33.5%), sheep 57 (28.1%), goats 16 (7.9%), donkey, 3 (1.5%) and pigs 59 (29.1%) respectively. The blood samples were collected from animals and examined in seven villages from two districts (Filiya and Lapan) of Shongom Local Government Area. These total numbers of 203 comprises 47 (23.2%) males and 156 (76.8%) females. From the males, 15 (31.9%) were cattle, 11 (23.4%) sheep, 5 (10.6%) goats, 0 (0.0%) donkey and 16 (34.0%) boar while the females consist of 53 (34.0%) cattle, 46 (29.5%) sheep, 11 (7.1%) goats, 3 (1.9%) donkeys and 43 (27.6%) sow. -

Gombe State Framework for the Implementation of Expanded Access to Family Planning Services 2013‒2018

Gombe State Framework for the Implementation of Expanded Access to Family Planning Services 2013-2018 December 2012 December 2012 Gombe State Framework for the Implementation of Expanded Access to Family Planning Services 2013-2018 December 2012 The Gombe State Framework for the Implementation of Expanded Access to Family Planning Services 2013 2018 was developed by the Gombe State Ministry of Health in July 2012. Financial Assistance for the framework was provided by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of the‒ Cooperative Agreement GPO – A-00-08-00001-00 through FHI 360’s Program Research for Strengthening Services (PROGRESS) project. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. government. This publication may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced or translated, in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. ©2012 Gombe State Ministry of Health, Nigeria First published in 2012 by the Gombe State Ministry of Health, Nigeria, with support from USAID– PROGRESS Citation: Gombe State Ministry of Health (SMoH). 2012. Gombe state framework for the implementation of expanded access to family planning services. Gombe (Nigeria): SMoH; 2012 Dec. TABLE OF CONTENTS LE OF CONTENTS Table of contents ................................................................................................................................... 1 Foreword ............................................................................................................................................... -

Making Sense of Resilience in the Boko Haram Crisis Akinola Olojo

Making sense of resilience in the Boko Haram crisis Akinola Olojo Major risk factors for violent extremism can be found in Bauchi and Gombe, two states in the north-east of Nigeria – the zone where the terror group Boko Haram is active. Yet in spite of risk factors, these two states have not experienced similar levels of violent extremism as other states in the same geographical zone. This study explains the synergy of issues that have shaped the narrative of resilience in Bauchi and Gombe over the last decade. WEST AFRICA REPORT 30 | JUNE 2020 Key findings Ethnic affiliation can be an important mobilisation and the organisations they lead have the skills factor for terror groups seeking to exploit it within required to address this concern. a geographical space. This has been the case with The unconventional nature of the war against terror Boko Haram and the Kanuri people in the countries of the Lake Chad Basin. groups such as Boko Haram can benefit from the contribution of community-based groups, such as Traditional institutions are an indispensable part vigilante organisations. of a society’s resilience framework. Their historical origins enable them to convey the depth of legitimacy Armed responses by the state play an essential role, required for communities to mobilise. but their limits are evident in a complex insurgency The ideological component of terrorism is as much that requires multiple levels of management to a threat as the violence it inspires. Religious leaders address the threat posed. Recommendations Traditional institutions such as the Bauchi and This creates a platform to facilitate dialogue as a way Gombe emirates, as well as local authorities at the of resolving disagreements before they escalate to district, ward and village level, should strengthen physical violence. -

Nigeria Security Situation

Nigeria Security situation Country of Origin Information Report June 2021 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu) PDF ISBN978-92-9465-082-5 doi: 10.2847/433197 BZ-08-21-089-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office, 2021 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the EASO copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. Cover photo@ EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid - Left with nothing: Boko Haram's displaced @ EU/ECHO/Isabel Coello (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0), 16 June 2015 ‘Families staying in the back of this church in Yola are from Michika, Madagali and Gwosa, some of the areas worst hit by Boko Haram attacks in Adamawa and Borno states. Living conditions for them are extremely harsh. They have received the most basic emergency assistance, provided by our partner International Rescue Committee (IRC) with EU funds. “We got mattresses, blankets, kitchen pots, tarpaulins…” they said.’ Country of origin information report | Nigeria: Security situation Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge Stephanie Huber, Founder and Director of the Asylum Research Centre (ARC) as the co-drafter of this report. The following departments and organisations have reviewed the report together with EASO: The Netherlands, Ministry of Justice and Security, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis Austria, Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum, Country of Origin Information Department (B/III), Africa Desk Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation (ACCORD) It must be noted that the drafting and review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

Downloaded from Divagis

© SEP 2019 | IRE Journals | Volume 3 Issue 3 | ISSN: 2456-8880 The Use of Location Quotient (L.Q) to Determine the Spatial Concentration of Health Care Facilities in Relation to Population in Gombe State ABUBAKAR ABDULLAHI1, UMAR YUSUF ABDULLAHI2 1,2 Department of Geography, Federal University Kashere, Gombe Abstract - Health care facilities are generally unevenly Hence, Government and other stakeholders are saddle distributed in many parts of the world, especially in with the responsibility to see that, healthcare facilities developing countries where the available facilities are and health workers are available, accessible and inadequate in relation to the potentially health seeking affordable to the populace, (Abdullahi, Abdullahi, population. This paper aimed to study the spatial Abbas, Bibi,and Bara, 2019). distribution of public health care facilities in Gombe State. The study therefore, focused on understanding the Many health care policies were established in Nigeria availability, location and spatial distribution and in different years such as that of 1988, 2004 and 2016 concentration of public healthcare facilities in Gombe State. Secondary data of public healthcare facilities was national policies on health systems, all these were obtained from Gombe State Primary Health Care done with the purpose to strengthen and improving the Development Agency (GSPHCDA); Location Quotient and performance of the health systems in the country, GIS techniques were applied to identify areas with surplus (National Health Policy, 2016). However, with all the and deficit public healthcare facilities in the state in above efforts of Nigerian Government, proper health relation to population. The results show that, five (5) Local care provision and deliveries are far below standard. -

A Wet Season Survey of Animal Trypanosomosis in Shongom Local Government Area of Gombe State. Nigeria Shamaki, BU1*, Obaloto

J. Protozool. Res. 19, 1-6 (2009) Copyright 2008, National Research Center for Protozoan Diseases A wet season survey of animal trypanosomosis in Shongom local government area of Gombe state. Nigeria Shamaki, B.U.1*, Obaloto, O.B.1, Kalejaiye, J.O.1, Lawani, F.A.G.2, Balak, G.G.1 and Charles D.1 1Nigerian Institute for Trypanosomiasis and Onchocerciasis Research (NITOR) Vom., 2NITOR, Kaduna, Nigeria *Corresponding author: Dr. Shamaki Bala Usman,E-mail: [email protected]. ABSTRACT Two hundred and three (203) blood samples were collected from randomly selected herd comprising; cattle, 68 (33.5%), sheep 57 (28.1%), goats 16 (7.9%), donkey, 3 (1.5%) and pigs 59 (29.1%) respectively. The blood samples were collected from animals and examined in seven villages from two districts (Filiya and Lapan) of Shongom Local Government Area. These total numbers of 203 comprises 47 (23.2%) males and 156 (76.8%) females. From the males, 15 (31.9%) were cattle, 11 (23.4%) sheep, 5 (10.6%) goats, 0 (0.0%) donkey and 16 (34.0%) boar while the females consist of 53 (34.0%) cattle, 46 (29.5%) sheep, 11 (7.1%) goats, 3 (1.9%) donkeys and 43 (27.6%) sow. The blood samples from these animals were analysed using a combination of thin and thick blood films and concentration methods. Eleven (5.42%) were found to be positive for hemoparasites. These comprise. Trypanosoma vivax 1 (9.1%), Microfilariae 1 (9.1%), Babesia 8 (72.7%) and 1 (9.1%) Anaplasma. The average packed cell volume (PCV) for infected and non infected males were 33.1 3.3 and 33.4 1.5 while that of females 31.5 5.1 and 31.9 0.8 respectively.