Leseprobe 9783791354422.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Very Special Arts Festival 1980 Bytmc 105

Interim Designation of Agent to Receive Notification of Claimed Infringement Full Legal Name of Service Provider: -------- -------- The Performing Arts Center of Los Angeles County Alternative Name(s) of Service Provider (including all names unde1· which the service provider is doing business): __S_ ee_ A_tt_ac_h_ed_ ________ ______ Address of Service Provider: 135 N. Grand Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90012 Name of Agent Designated to Receive Notification of Claimed Infringement:_L_i_sa_W_ h_itne__y______ _____ _ Full Address of Designated Agent to which Notification Should be Sent (a P.O. Box or similar designation is not acceptable except where it is the only address that can be used in the geographic location): The Music Center, 135 N. Grand Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90012 Telephone Number of Designated Agent:_(_21_3_)_9_72_-_75_1_2______ ___ _ Facsimile Number of Designated Agent:_(_2_13_)_9_7_2-_7_248__ __________ Email Address of Designated Agent: [email protected] ative of the Designating Service Provider: Date: February 24, 2016 Typed or Printed Name and Title: Lisa Whitney, SVP Finance & CFO Note: This Interim Designation Must be Accompanied by a Filing Fee* Made Payable to the Register of Copyrights. *Note: Current and adjusted fees are available on the Copyright website at www.copyright.gov/docs/fees.html Mail the form to: U.S. Copyright Office, Designated Agents P.O. Box 71537 Washington, DC 20024-1537 SCANNED Received APR 18 2017 MAR 1 0 2016 ·copyright Office 2014 135832 11111~ ~rn 11111 111~ ~1111111 m111111111111 mH111rn FILED EXPIRES Mey 19 2014 May 19 2019 Additional Fictitious Names Fictitious Business Na me In Use Sine& 1. -

The Fondation Louis Vuitton

THE FONDATION LOUIS VUITTON A new ambition for LVMH's corporate patronage Created by the LVMH group and its Maisons in 2006 on the initiative of Bernard Arnault, the Fondation Louis Vuitton forms part of the art and culture patronage programme developed by the group for over twenty years. It also marks a new step driven by a renewed ambition: – A lasting commitment with the desire to become firmly rooted in a particular place and bring an institution to life over the long term. – A major philanthropic gesture towards the city of Paris with the construction of an exceptional building on municipal state property and the signature of a 55-year occupancy agreement with Paris city council. Driven by a desire to work for the common good, the Fondation Louis Vuitton demonstrates a clear commitment to contemporary art and looks to make it accessible to as many people as possible. To foster the creation of contemporary art on a national and international scale, the Fondation Louis Vuitton calls on a permanent collection, commissions from artists, temporary modern and contemporary art exhibitions and multidisciplinary events. One of its priorities is to fulfil an educational role, especially among the young. A new monument for Paris Frank Gehry has designed a building that, through its strength and singularity, represents the first artistic step on the part of the Fondation Louis Vuitton. This large vessel covered in twelve glass sails, situated in the Bois de Boulogne, on the edge of avenue du Mahatma Gandhi, is attached to the Jardin d'Acclimatation. Set on a water garden created for the occasion, the building blends into the natural environment, amidst the wood and the garden, playing with light and mirror effects. -

The Abuse of Architectonics by Decorating in an Era After Deconstructivism

THE ABUSE OF ARCHITECTONICS BY DECORATING IN AN ERA AFTER DECONSTRUCTIVISM DECONSTRUCTION OF THE TECTONIC STRUCTURE AS A WAY OF DECORATION PIM GERRITSEN | 1186272 MSC3 | INTERIORS, BUILDINGS, CITIES | STUDIO BACK TO SCHOOL AR0830 ARCHITECTURE THEORY | ARCHITECTURAL THINKING | GRADUATION THESIS FALL SEMESTER 2008-2009 | MARCH 09 THESIS | ARCHITECTURAL THINKING | AR0830 | PIM GERRITSEN | 1186272 | MAR-09 | P. 1 ‘In fact, all architecture proceeds from structure, and the first condition at which it should aim is to make the outward form accord with that structure.’ 1 Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (1872) Lectures Everything depends upon how one sets it to work… little by little we modify the terrain of our work and thereby produce new configurations… it is essential, systematic, and theoretical. And this in no way minimizes the necessity and relative importance of certain breaks of appearance and definition of new structures…’ 2 Jacques Derrida (1972) Positions ‘It is ironic that the work of Coop Himmelblau, and of other deconstructive architects, often turns out to demand far more structural ingenuity than works developed with a ‘rational’ approach to structure.’ 3 Adrian Forty (2000) Words and Buildings Theme In recent work of architects known as deconstructivists the tectonic structure of the buildings seems to be ‘deconstructed’ in order to decorate the building’s image. In other words: nowadays deconstruction has become a style with the architectonic structure used as decoration. Is the show of architectonic elements in recent work of -

Helen Pashgianhelen Helen Pashgian L Acm a Delmonico • Prestel

HELEN HELEN PASHGIAN ELIEL HELEN PASHGIAN LACMA DELMONICO • PRESTEL HELEN CAROL S. ELIEL PASHGIAN 9 This exhibition was organized by the Published in conjunction with the exhibition Helen Pashgian: Light Invisible Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Funding at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California is provided by the Director’s Circle, with additional support from Suzanne Deal Booth (March 30–June 29, 2014). and David G. Booth. EXHIBITION ITINERARY Published by the Los Angeles County All rights reserved. No part of this book may Museum of Art be reproduced or transmitted in any form Los Angeles County Museum of Art 5905 Wilshire Boulevard or by any means, electronic or mechanical, March 30–June 29, 2014 Los Angeles, California 90036 including photocopy, recording, or any other (323) 857-6000 information storage and retrieval system, Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Nashville www.lacma.org or otherwise without written permission from September 26, 2014–January 4, 2015 the publishers. Head of Publications: Lisa Gabrielle Mark Editor: Jennifer MacNair Stitt ISBN 978-3-7913-5385-2 Rights and Reproductions: Dawson Weber Creative Director: Lorraine Wild Designer: Xiaoqing Wang FRONT COVER, BACK COVER, Proofreader: Jane Hyun PAGES 3–6, 10, AND 11 Untitled, 2012–13, details and installation view Formed acrylic 1 Color Separator, Printer, and Binder: 12 parts, each approx. 96 17 ⁄2 20 inches PR1MARY COLOR In Helen Pashgian: Light Invisible, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2014 This book is typeset in Locator. PAGE 9 Helen Pashgian at work, Pasadena, 1970 Copyright ¦ 2014 Los Angeles County Museum of Art Printed and bound in Los Angeles, California Published in 2014 by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art In association with DelMonico Books • Prestel Prestel, a member of Verlagsgruppe Random House GmbH Prestel Verlag Neumarkter Strasse 28 81673 Munich Germany Tel.: +49 (0)89 41 36 0 Fax: +49 (0)89 41 36 23 35 Prestel Publishing Ltd. -

Press Release Frank Gehry First Major European

1st August 2014 PRESS RELEASE communications and partnerships department 75191 Paris cedex 04 FRANK GEHRY director Benoît Parayre telephone FIRST MAJOR EUROPEAN 00 33 (0)1 44 78 12 87 e-mail [email protected] RETROSPECTIVE press officer 8 OCTOBER 2014 - 26 JANUARY 2015 Anne-Marie Pereira telephone GALERIE SUD, LEVEL 1 00 33 (0)1 44 78 40 69 e-mail [email protected] www.centrepompidou.fr For the first time in Europe, the Centre Pompidou is to present a comprehensive retrospective of the work of Frank Gehry, one of the great figures of contemporary architecture. Known all over the world for his buildings, many of which have attained iconic status, Frank Gehry has revolutionised architecture’s aesthetics, its social and cultural role, and its relationship to the city. It was in Los Angeles, in the early 1960s, that Gehry opened his own office as an architect. There he engaged with the California art scene, becoming friends with artists such as Ed Ruscha, Richard Serra, Claes Oldenburg, Larry Bell, and Ron Davis. His encounter with the works of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns would open the way to a transformation of his practice as an architect, for which his own, now world-famous, house at Santa Monica would serve as a manifesto. Frank Gehry’s work has since then been based on the interrogation of architecture’s means of expression, a process that has brought with it new methods of design and a new approach to materials, with for example the use of such “poor” materials as cardboard, sheet steel and industrial wire mesh. -

President's Message

July/Aug 2021 Vol 56-4 63 Years of Dedicated Service to L.A. Your Pension and Health Care Watchdog County Retirees www.relac.org • e-mail: [email protected] • (800) 537-3522 RELAC Joins National Group to Lobby President’s Against Unfair Social Security Reductions Message RELAC has joined the national Alliance for Public Retirees by Brian Berger to support passage of H.R. 2337, proposed legislation to reform the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) of the Social The recovery appears to be on a real path Security Act. to becoming a chapter of our history with whatever sadness or tragedy of which The Alliance for Public Retirees was created nearly a decade we might each have witnessed or been ago by the Retired State, County and Municipal Employees a part. The next few months will be critical as we continue to Association of Massachusetts (Mass Retirees) and the Texas see a further lessening or elimination of restrictions. I don't Retired Teachers Association to resolve the issues of WEP know how I'll ever be able to leave the house or see friends and the Government Pension Offset (GPO). without a mask, at least in the car or in my pocket. In all this Together with retiree organizations, public employee unions past period, however, work has not lessened at RELAC and the and civic associations across the country, the organization programs have continued with positive gains. For that I thank has worked to advance federal legislation through Congress the support staff, each Board member, and the many of you aimed at reforming both the WEP and GPO laws. -

This File Was Downloaded From

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queensland University of Technology ePrints Archive This is the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for pub- lication in the following source: Brott, Simone (2012) Modernity’s opiate, or the crisis of iconic architecture. Log, 26, pp. 49-59. This file was downloaded from: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/47848/ c Copyright 2012 Anyone Corporation Notice: Changes introduced as a result of publishing processes such as copy-editing and formatting may not be reflected in this document. For a definitive version of this work, please refer to the published source: Brott DRAFT – 10/22/12 1 Modernity’s Opiate, or the Crisis of Iconic Architecture Log 26 Simone Brott Theodor Adorno was opposed to cinema because he felt it was too close to reality, and thus an extension of ideological capital.1 What troubled Adorno was the iconic nature of cinema – its ability to mimic the formal visual qualities of its referent.2 For the postwar, Hollywood-film spectator, Adorno said, “the world outside is an extension of the film he has just left,” because realism is a precise instrument for the manipulation of the mass spectator by the culture industry, for which the filmic image is an advertisement for the world unedited.3 Mimesis, or the reproduction of reality, is a “mere reproduction of the economic base.”4 It is precisely film’s iconicity, then, its “realist aesthetic . [that] makes it inseparable from its commodity character.”5 Adorno’s critique of what is facile in the cinematic image – its false immediacy – glimmers in the ubiquitous yet misunderstood term “iconic architecture” of our own episteme. -

Schedule and Cost Estimate for an Innovative Boston Harbor Concert Hall

Schedule and Cost Estimate for an Innovative Boston Harbor Concert Hall by Amelie Coste B.S., Civil and Environmental Engineering Ecole Speciale des Travaux Publics, 2003 Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2004 © 2004 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved Signature of A uthor..................... ........................ Deplrtment of Civil And Environmental Engineering n May 7, 2004 Certified by........................... Jerome J Connor Professor of Civil and Envir nmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor Certified by..................... ......................... ACA ' 1 Nathaniel Osgood IA Sepior4urer of il and Environmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted by .............. ............................ Heidi Nepf Chairman, Committee for Graduate Students MASSACHUSETTS INS OF TECHNOLOGY JUN 0 7 200 4] BARKER LIBRARIE S Schedule and Cost Estimate for an Innovative Boston Harbor Concert Hall By Amelie Coste Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 7, 2004 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering ABSTRACT This thesis formulates a cost estimate and schedule for constructing the Boston Concert Hall, an innovative hypothetical building composed of two concert halls and a restaurant. Concert Halls are complex and expensive structures due to steep design requirements reflecting their status as signature buildings and because they require extensive furnishing. Restaurants are not as complex but require the same kind of attention in their interior furnishing as well as in the choice of their kitchen equipment. Because the structure houses two complicated entities, feasibility analysis required a careful cost and schedule estimation. -

Size, Scale and the Imaginary in the Work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim

Larger than life: size, scale and the imaginary in the work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim © Michael Albert Hedger A thesis in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Art History and Art Education UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES | Art & Design August 2014 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Hedger First name: Michael Other name/s: Albert Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: Ph.D. School: Art History and Education Faculty: Art & Design Title: Larger than life: size, scale and the imaginary in the work of Land Artists Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria and Dennis Oppenheim Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Conventionally understood to be gigantic interventions in remote sites such as the deserts of Utah and Nevada, and packed with characteristics of "romance", "adventure" and "masculinity", Land Art (as this thesis shows) is a far more nuanced phenomenon. Through an examination of the work of three seminal artists: Michael Heizer (b. 1944), Dennis Oppenheim (1938-2011) and Walter De Maria (1935-2013), the thesis argues for an expanded reading of Land Art; one that recognizes the significance of size and scale but which takes a new view of these essential elements. This is achieved first by the introduction of the "imaginary" into the discourse on Land Art through two major literary texts, Swift's Gulliver's Travels (1726) and Shelley's sonnet Ozymandias (1818)- works that, in addition to size and scale, negotiate presence and absence, the whimsical and fantastic, longevity and death, in ways that strongly resonate with Heizer, De Maria and especially Oppenheim. -

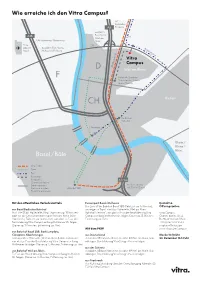

Anfahrt DE.Pdf

Wie erreiche ich den Vitra Campus? A5 Karlsruhe / A5 Freiburg Ausfahrt / Exit / Sortie A35 B3 Weil am A35 Strassburg / Strasbourg Rhein Euro E35 Airport Ausfahrt / Exit / Sortie Rö Basel Mulhouse / Freiburg me rstras se Vitra Campus Müllheimer Str. Bahnhof / Zentrum Train station / Centre Gare / Centre Badischer Bahnhof Claraplatz 55 Rhein / Rhine / Rhin Basel / Bâle Zug / Train Tram Bus Fussweg / Footpath / A2/A3 Chemin pédestre 8 2 Landesgrenze / A2 Bern / Berne National border / Bahnhof SBB A3 Zürich / Zurich Frontière nationale Mit den öffentlichen Verkehrsmitteln Euroairport Basel/Mulhouse Kontakt & Bus Linie 50 bis Bahnhof Basel SBB (Fahrtzeit ca. 15 Minuten), Öffnungszeiten von Basel Badischer Bahnhof umsteigen in Tram Linie 8 bis Haltestelle „Weil am Rhein Bus Linie 55 bis Haltestelle „Vitra“ (Fahrtzeit ca. 15 Minuten) Bahnhof/Zentrum“, von dort zu Fuss der Beschilderung Vitra Vitra Campus oder mit der Deutschen Bahn nach Weil am Rhein (eine Campus entlang Müllheimer Str. folgen (Dauer ca. 15 Minuten, Charles-Eames-Str. 2 Haltestelle, Fahrzeit ca. 5 Minuten), von dort zu Fuss der Entfernung ca. 1 km) D-79576 Weil am Rhein Beschilderung Vitra Campus entlang Müllheimer Str. folgen +49 (0)7621 702 3500 (Dauer ca. 15 Minuten, Entfernung ca. 1 km) [email protected] Mit dem PKW www.vitra.com/campus von Bahnhof Basel SBB, Barfüsserplatz, Claraplatz, Kleinhüningen aus Deutschland Mo-So 10-18 Uhr Tram Linie 8 bis Haltestelle „Weil am Rhein Bahnhof/Zentrum“, Autobahn A5 Karlsruhe-Basel, Ausfahrt 69 Weil am Rhein, links 24. Dezember 10-14 Uhr von dort zu Fuss der Beschilderung Vitra Campus entlang abbiegen, Beschilderung Vitra Design Museum folgen Müllheimer Str. -

Frank Gehry Biography

G A G O S I A N Frank Gehry Biography Born in 1929 in Toronto, Canada. Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA. Education: 1954 B.A., University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA. 1956 M.A., Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. Select Solo Exhibitions: 2021 Spinning Tales. Gagosian, Beverly Hills, CA. 2016 Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Rome, Italy. Building in Paris. Espace Louis Vuitton Venezia, Venice, Italy. 2015 Architect Frank Gehry: “I Have an Idea.” 21_21 Design Sight, Tokyo, Japan. 2015 Frank Gehry. LACMA, Los Angeles, CA. 2014 Frank Gehry. Centre Pompidou, Paris, France. Voyage of Creation. Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris, France. Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Athens, Greece. Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Hong Kong, China. 2013 Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Davies Street, London, England. Frank Gehry At Work. Leslie Feely Fine Art. New York, NY. Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Paris Project Space, Paris, France. Frank Gehry at Gemini: New Sculpture & Prints, with a Survey of Past Projects. Gemini G.E.L. at Joni Moisant Weyl, New York, NY. Fish Lamps. Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA. 2011 Frank Gehry: Outside The Box. Artistree, Hong Kong, China. 2010 Frank O. Gehry since 1997. Vitra Design Museum, Rhein, Germany. Frank Gehry: Eleven New Prints. Gemini G.E.L. at Joni Moisant Weyl, New York, NY. 2008 Frank Gehry: Process Models and Drawings. Leslie Feely Fine Art, New York, NY. 2006 Frank Gehry: Art + Architecture. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada. 2003 Frank Gehry, Architect: Designs for Museums. Weisman Art Museum, Minneapolis, MN. Traveled to Corcoran Art Gallery, Washington, D.C. 2001 Frank Gehry, Architect. -

Michael Govan Is the CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

Michael Govan is the CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Since coming to LACMA in 2006 he has overseen the transformation of the 20–acre campus with buildings by Renzo Piano and monumental artworks by Chris Burden, Michael Heizer, Robert Irwin, Barbara Kruger, and others. At LACMA, Govan has pursued his vision of contemporary artists and architects interacting with the museum’s historic collections, as evidenced by exhibition and gallery designs in collaboration with artists John Baldessari, Jorge Pardo, and Franz West, and architects Frank O. Gehry, Fred Fisher, Michael Maltzan, and others. Under his leadership, LACMA has acquired nearly 35,000 works, building and expanding its collection of works from Latin America, Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and the Pacific. In 2015, Govan undertook the museum’s most successful art gift campaign in honor of LACMA’s 50th anniversary, as well as the most significant bequest in the museum’s history, the Perenchio collection of Impressionist and early 20th-century art. Known as well for his curatorial work, Govan has co-curated a series of notable exhibitions including Picasso and Rivera: Conversations Across Time (2016–17), James Turrell: A Retrospective (2013–14), and The Presence of the Past: Peter Zumthor Reconsiders LACMA (2013), which presented plans for a future building for the museum designed by the Pritzker Prize–winning architect. Govan was the co- curator of the touring exhibition Dan Flavin: A Retrospective, organized by Dia:Beacon in association with the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. The exhibition concluded its international tour at LACMA, where it was on view, May 13–August 12, 2007.