Galactic Astronomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ASTR 503 – Galactic Astronomy Spring 2015 COURSE SYLLABUS

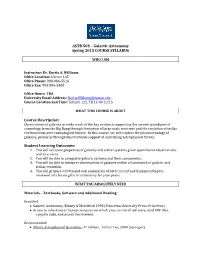

ASTR 503 – Galactic Astronomy Spring 2015 COURSE SYLLABUS WHO I AM Instructor: Dr. Kurtis A. Williams Office Location: Science 145 Office Phone: 903-886-5516 Office Fax: 903-886-5480 Office Hours: TBA University Email Address: [email protected] Course Location and Time: Science 122, TR 11:00-12:15 WHAT THIS COURSE IS ABOUT Course Description: Observations of galaxies provide much of the key evidence supporting the current paradigms of cosmology, from the Big Bang through formation of large-scale structure and the evolution of stellar environments over cosmological history. In this course, we will explore the phenomenology of galaxies, primarily through observational support of underlying astrophysical theory. Student Learning Outcomes: 1. You will calculate properties of galaxies and stellar systems given quantitative observations, and vice-versa. 2. You will be able to categorize galactic systems and their components. 3. You will be able to interpret observations of galaxies within a framework of galactic and stellar evolution. 4. You will prepare written and oral summaries of both current and fundamental peer- reviewed articles on galactic astronomy for your peers. WHAT YOU ABSOLUTELY NEED Materials – Textbooks, Software and Additional Reading: Required: • Galactic Astronomy, Binney & Merrifield 1998 (Princeton University Press: Princeton) • Access to a desktop or laptop computer on which you can install software, read PDF files, compile code, and access the internet. Recommended: • Allen’s Astrophysical Quantities, 4th Edition, Arthur Cox, 2000 (Springer) Course Prerequisites: Advanced undergraduate classical dynamics (equivalent of Phys 411) or Phys 511. HOW THE COURSE WILL WORK Instructional Methods / Activities / Assessments Assigned Readings There is far too much material in the text for us to cover every single topic in class. -

The Solar System and Its Place in the Galaxy in Encyclopedia of the Solar System by Paul R

Giant Molecular Clouds http://www.astro.ncu.edu.tw/irlab/projects/project.htm Æ Galactic Open Clusters Æ Galactic Structure Æ GMCs The Solar System and its Place in the Galaxy In Encyclopedia of the Solar System By Paul R. Weissman http://www.academicpress.com/refer/solar/Contents/chap1.htm Stars in the galactic disk have different characteristic velocities as a function of their stellar classification, and hence age. Low-mass, older stars, like the Sun, have relatively high random velocities and as a result c an move farther out of the galactic plane. Younger, more massive stars have lower mean velocities and thus smaller scale heights above and below the plane. Giant molecular clouds, the birthplace of stars, also have low mean velocities and thus are confined to regions relatively close to the galactic plane. The disk rotates clockwise as viewed from "galactic north," at a relatively constant velocity of 160-220 km/sec. This motion is distinctly non-Keplerian, the result of the very nonspherical mass distribution. The rotation velocity for a circular galactic orbit in the galactic plane defines the Local Standard of Rest (LSR). The LSR is then used as the reference frame for describing local stellar dynamics. The Sun and the solar system are located approxi-mately 8.5 kpc from the galactic center, and 10-20 pc above the central plane of the galactic disk. The circular orbit velocity at the Sun's distance from the galactic center is 220 km/sec, and the Sun and the solar system are moving at approximately 17 to 22 km/sec relative to the LSR. -

Stellar Dynamics and Stellar Phenomena Near a Massive Black Hole

Stellar Dynamics and Stellar Phenomena Near A Massive Black Hole Tal Alexander Department of Particle Physics and Astrophysics, Weizmann Institute of Science, 234 Herzl St, Rehovot, Israel 76100; email: [email protected] | Author's original version. To appear in Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. See final published version in ARA&A website: www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-astro-091916-055306 Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2017. Keywords 55:1{41 massive black holes, stellar kinematics, stellar dynamics, Galactic This article's doi: Center 10.1146/((please add article doi)) Copyright c 2017 by Annual Reviews. Abstract All rights reserved Most galactic nuclei harbor a massive black hole (MBH), whose birth and evolution are closely linked to those of its host galaxy. The unique conditions near the MBH: high velocity and density in the steep po- tential of a massive singular relativistic object, lead to unusual modes of stellar birth, evolution, dynamics and death. A complex network of dynamical mechanisms, operating on multiple timescales, deflect stars arXiv:1701.04762v1 [astro-ph.GA] 17 Jan 2017 to orbits that intercept the MBH. Such close encounters lead to ener- getic interactions with observable signatures and consequences for the evolution of the MBH and its stellar environment. Galactic nuclei are astrophysical laboratories that test and challenge our understanding of MBH formation, strong gravity, stellar dynamics, and stellar physics. I review from a theoretical perspective the wide range of stellar phe- nomena that occur near MBHs, focusing on the role of stellar dynamics near an isolated MBH in a relaxed stellar cusp. -

PHYS 1302 Intro to Stellar & Galactic Astronomy

PHYS 1302: Introduction to Stellar and Galactic Astronomy University of Houston-Downtown Course Prefix, Number, and Title: PHYS 1302: Introduction to Stellar and Galactic Astronomy Credits/Lecture/Lab Hours: 3/2/2 Foundational Component Area: Life and Physical Sciences Prerequisites: Credit or enrollment in MATH 1301 or MATH 1310 Co-requisites: None Course Description: An integrated lecture/laboratory course for non-science majors. This course surveys stellar and galactic systems, the evolution and properties of stars, galaxies, clusters of galaxies, the properties of interstellar matter, cosmology and the effort to find extraterrestrial life. Competing theories that address recent discoveries are discussed. The role of technology in space sciences, the spin-offs and implications of such are presented. Visual observations and laboratory exercises illustrating various techniques in astronomy are integrated into the course. Recent results obtained by NASA and other agencies are introduced. Up to three evening observing sessions are required for this course, one of which will take place off-campus at George Observatory at Brazos Bend State Park. TCCNS Number: N/A Demonstration of Core Objectives within the Course: Assigned Core Learning Outcome Instructional strategy or content Method by which students’ Objective Students will be able to: used to achieve the outcome mastery of this outcome will be evaluated Critical Thinking Utilize scientific Star Property Correlations – They will be instructed to processes to identify students will form and test prioritize these properties in Empirical & questions pertaining to hypotheses to explain the terms of their relevance in Quantitative natural phenomena. correlation between a number of deciding between competing Reasoning properties seen in stars. -

Galactic Astronomy with AO: Nearby Star Clusters and Moving Groups

Galactic astronomy with AO: Nearby star clusters and moving groups T. J. Davidgea aDominion Astrophysical Observatory, Victoria, BC Canada ABSTRACT Observations of Galactic star clusters and objects in nearby moving groups recorded with Adaptive Optics (AO) systems on Gemini South are discussed. These include observations of open and globular clusters with the GeMS system, and high Strehl L observations of the moving group member Sirius obtained with NICI. The latter data 2 fail to reveal a brown dwarf companion with a mass ≥ 0.02M in an 18 × 18 arcsec area around Sirius A. Potential future directions for AO studies of nearby star clusters and groups with systems on large telescopes are also presented. Keywords: Adaptive optics, Open clusters: individual (Haffner 16, NGC 3105), Globular Clusters: individual (NGC 1851), stars: individual (Sirius) 1. STAR CLUSTERS AND THE GALAXY Deep surveys of star-forming regions have revealed that stars do not form in isolation, but instead form in clusters or loose groups (e.g. Ref. 25). This is a somewhat surprising result given that most stars in the Galaxy and nearby galaxies are not seen to be in obvious clusters (e.g. Ref. 31). This apparent contradiction can be reconciled if clusters tend to be short-lived. In fact, the pace of cluster destruction has been measured to be roughly an order of magnitude per decade in age (Ref. 17), indicating that the vast majority of clusters have lifespans that are only a modest fraction of the dynamical crossing-time of the Galactic disk. Clusters likely disperse in response to sudden changes in mass driven by supernovae and stellar winds (e.g. -

Dwarfs Walking in a Row the filamentary Nature of the NGC 3109 Association

A&A 559, L11 (2013) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201322744 & c ESO 2013 Astrophysics Letter to the Editor Dwarfs walking in a row The filamentary nature of the NGC 3109 association M. Bellazzini1, T. Oosterloo2;3, F. Fraternali4;3, and G. Beccari5 1 INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Bologna, via Ranzani 1, 40127 Bologna, Italy e-mail: [email protected] 2 Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, Postbus 2, 7990 AA Dwingeloo, The Netherlands 3 Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, Postbus 800, 9700 AV Groningen, The Netherlands 4 Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia - Università degli Studi di Bologna, viale Berti Pichat 6/2, 40127 Bologna, Italy 5 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching bei Munchen, Germany Received 24 September 2013 / Accepted 22 October 2013 ABSTRACT We re-consider the association of dwarf galaxies around NGC 3109, whose known members were NGC 3109, Antlia, Sextans A, and Sextans B, based on a new updated list of nearby galaxies and the most recent data. We find that the original members of the NGC 3109 association, together with the recently discovered and adjacent dwarf irregular Leo P, form a very tight and elongated configuration in space. All these galaxies lie within ∼100 kpc of a line that is '1070 kpc long, from one extreme (NGC 3109) to the other (Leo P), and they show a gradient in the Local Group standard of rest velocity with a total amplitude of 43 km s−1 Mpc−1, and a rms scatter of just 16.8 km s−1. It is shown that the reported configuration is exceptional given the known dwarf galaxies in the Local Group and its surroundings. -

Astr-Astronomy 1

ASTR-ASTRONOMY 1 ASTR 1116. Introduction to Astronomy Lab, Special ASTR-ASTRONOMY 1 Credit (1) This lab-only listing exists only for students who may have transferred to ASTR 1115G. Introduction Astro (lec+lab) NMSU having taken a lecture-only introductory astronomy class, to allow 4 Credits (3+2P) them to complete the lab requirement to fulfill the general education This course surveys observations, theories, and methods of modern requirement. Consent of Instructor required. , at some other institution). astronomy. The course is predominantly for non-science majors, aiming Restricted to Las Cruces campus only. to provide a conceptual understanding of the universe and the basic Prerequisite(s): Must have passed Introduction to Astronomy lecture- physics that governs it. Due to the broad coverage of this course, the only. specific topics and concepts treated may vary. Commonly presented Learning Outcomes subjects include the general movements of the sky and history of 1. Course is used to complete lab portion only of ASTR 1115G or ASTR astronomy, followed by an introduction to basic physics concepts like 112 Newton’s and Kepler’s laws of motion. The course may also provide 2. Learning outcomes are the same as those for the lab portion of the modern details and facts about celestial bodies in our solar system, as respective course. well as differentiation between them – Terrestrial and Jovian planets, exoplanets, the practical meaning of “dwarf planets”, asteroids, comets, ASTR 1120G. The Planets and Kuiper Belt and Trans-Neptunian Objects. Beyond this we may study 4 Credits (3+2P) stars and galaxies, star clusters, nebulae, black holes, and clusters of Comparative study of the planets, moons, comets, and asteroids which galaxies. -

Galaxies: Outstanding Problems and Instrumental Prospects for the Coming Decade (A Review)* T (Cosmology/History of Astronomy/Quasars/Space) JEREMIAH P

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 74, No. 5, pp. 1767-1774, May 1977 Astronomy Galaxies: Outstanding problems and instrumental prospects for the coming decade (A Review)* t (cosmology/history of astronomy/quasars/space) JEREMIAH P. OSTRIKER Princeton University Observatory, Peyton Hall, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 Contributed by Jeremiah P. Ostriker, February 3, 1977 ABSTRACT After a review of the discovery of external It is more than a little astonishing that in the early part of this galaxies and the early classification of these enormous aggre- century it was the prevailing scientific view that man lived in gates of stars into visually recognizable types, a new classifi- a universe centered about himself; by 1920 the sun's newly cation scheme is suggested based on a measurable physical quantity, the luminosity of the spheroidal component. It is ar- discovered, slightly off-center position was still controversial. gued that the new one-parameter scheme may correlate well The discovery was, ironically, due to Shapley. both with existing descriptive labels and with underlying A little background to this debate may be useful. The Island physical reality. Universe hypothesis was not new, having been proposed 170 Two particular problems in extragalactic research are isolated years previously by the English astronomer, Thomas Wright as currently most fundamental. (i) A significant fraction of the (2), and developed with remarkably prescience by Emmanuel energy emitted by active galaxies (approximately 1% of all galaxies) is emitted by very small central regions largely in parts Kant, who wrote (see refs. 10 and 23 in ref. 3) in 1755 (in a of the spectrum (microwave, infrared, ultraviolet and x-ray translation from Edwin Hubble). -

Systematic Motions in the Galactic Plane Found in the Hipparcos

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. cabad0609 September 30, 2018 (DOI: will be inserted by hand later) Systematic motions in the galactic plane found in the Hipparcos Catalogue using Herschel’s Method Carlos Abad1,2 & Katherine Vieira1,3 (1) Centro de Investigaciones de Astronom´ıa CIDA, 5101-A M´erida, Venezuela e-mail: [email protected] (2) Grupo de Mec´anica Espacial, Depto. de F´ısica Te´orica, Universidad de Zaragoza. 50006 Zaragoza, Espa˜na (3) Department of Astronomy, Yale University, P.O. Box 208101 New Haven, CT 06520-8101, USA e-mail: [email protected] September 30, 2018 Abstract. Two motions in the galactic plane have been detected and characterized, based on the determination of a common systematic component in Hipparcos catalogue proper motions. The procedure is based only on positions, proper motions and parallaxes, plus a special algorithm which is able to reveal systematic trends. Our results come o o o o from two stellar samples. Sample 1 has 4566 stars and defines a motion of apex (l,b) = (177 8, 3 7) ± (1 5, 1 0) and space velocity V = 27 ± 1 km/s. Sample 2 has 4083 stars and defines a motion of apex (l,b)=(5o4, −0o6) ± o o (1 9, 1 1) and space velocity V = 32 ± 2 km/s. Both groups are distributed all over the sky and cover a large variety of spectral types, which means that they do not belong to a specific stellar population. Herschel’s method is used to define the initial samples of stars and later to compute the common space velocity. -

ASTRON 449: Stellar Dynamics Winter 2017 in This Course, We Will Cover

ASTRON 449: Stellar Dynamics Winter 2017 In this course, we will cover • the basic phenomenology of galaxies (including dark matter halos, stars clusters, nuclear black holes) • theoretical tools for research on galaxies: potential theory, orbit integration, statistical description of stellar systems, stability of stellar systems, disk dynamics, interactions of stellar systems • numerical methods for N-body simulations • time permitting: kinetic theory, basics of galaxy formation Galaxy phenomenology Reading: BT2, chap. 1 intro and section 1.1 What is a galaxy? The Milky Way disk of stars, dust, and gas ~1011 stars 8 kpc 1 pc≈3 lyr Sun 6 4×10 Msun black hole Gravity turns gas into stars (all in a halo of dark matter) Galaxies are the building blocks of the Universe Hubble Space Telescope Ultra-Deep Field Luminosity and mass functions MW is L* galaxy Optical dwarfs Near UV Schechter fits: M = 2.5 log L + const. − 10 Local galaxies from SDSS; Blanton & Moustakas 08 Hubble’s morphological classes bulge or spheroidal component “late type" “early type" barred http://skyserver.sdss.org/dr1/en/proj/advanced/galaxies/tuningfork.asp Not a time or physical sequence Galaxy rotation curves: evidence for dark matter M33 rotation curve from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galaxy_rotation_curve Galaxy clusters lensing arcs Abell 1689 ‣ most massive gravitational bound objects in the Universe ‣ contain up to thousands of galaxies ‣ most baryons intracluster gas, T~107-108 K gas ‣ smaller collections of bound galaxies are called 'groups' Bullet cluster: more -

Observational Cosmology - 30H Course 218.163.109.230 Et Al

Observational cosmology - 30h course 218.163.109.230 et al. (2004–2014) PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 31 Oct 2013 03:42:03 UTC Contents Articles Observational cosmology 1 Observations: expansion, nucleosynthesis, CMB 5 Redshift 5 Hubble's law 19 Metric expansion of space 29 Big Bang nucleosynthesis 41 Cosmic microwave background 47 Hot big bang model 58 Friedmann equations 58 Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric 62 Distance measures (cosmology) 68 Observations: up to 10 Gpc/h 71 Observable universe 71 Structure formation 82 Galaxy formation and evolution 88 Quasar 93 Active galactic nucleus 99 Galaxy filament 106 Phenomenological model: LambdaCDM + MOND 111 Lambda-CDM model 111 Inflation (cosmology) 116 Modified Newtonian dynamics 129 Towards a physical model 137 Shape of the universe 137 Inhomogeneous cosmology 143 Back-reaction 144 References Article Sources and Contributors 145 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 148 Article Licenses License 150 Observational cosmology 1 Observational cosmology Observational cosmology is the study of the structure, the evolution and the origin of the universe through observation, using instruments such as telescopes and cosmic ray detectors. Early observations The science of physical cosmology as it is practiced today had its subject material defined in the years following the Shapley-Curtis debate when it was determined that the universe had a larger scale than the Milky Way galaxy. This was precipitated by observations that established the size and the dynamics of the cosmos that could be explained by Einstein's General Theory of Relativity. -

Numerical Computations in Stellar Dynamics

Particle Accelerators, 1986, Vol. 19, pp. 37-42 0031-2460/86/1904-0037/$15.00/0 © 1986 Gordon and Breach, Science Publishers, S.A. Printed in the United States of America NUMERICAL COMPUTATIONS IN STELLAR DYNAMICS PIET HUTt Department ofAstronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 An outline is given of the main similarities and differences between gravitational dynamics and the other fields of interest at the present conference: accelerator orbital dynamics and plasma physics. Gravitational dynamics can be divided into two rather distinct fields, celestial mechanics and stellar dynamics. The field of stellar dynamics is concerned with astrophysical applications of the general gravitational N -body problem, which addresses the question: for a system of N point masses with given initial conditions, describe its evolution under Newtonian gravity. Major subfields within stellar dynamics are listed and classified according to the collisional or collisionless character of different problems. A number of review papers are mentioned and briefly discussed, to provide a few starting points for exploring the vast recent literature on stellar dynamics. I. INTRODUCTION Gravitational dynamics naturally divides into two rather distinct fields, celestial mechanics and stellar dynamics. The former is concerned with the long-term evolution of well-behaved, small, and ordered systems such as the motion of the planets around the sun, and that of natural and artificial satellites around the sun and planets. The latter covers the behavior of much larger systems consisting of many particles, each of which move on random paths constrained only by a globally averaged distribution, just as atoms move in a gas.