Dialogues Across Disciplines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter Preview

2 C. Rajagopalachari 1 An Illustrious Life Great statesman and thinker, Rajagopalachari was born in Thorapalli in the then Salem district and was educated in Central College, Bangalore and Presidency College, Madras. Chakravarthi Rajagopalachari (10 December 1878 - 25 December 1972), informally called Rajaji or C.R., was an eminent lawyer, independence activist, politician, writer, statesman and leader of the Indian National Congress who served as the last Governor General of India. He served as the Chief Minister or Premier of the Madras Presidency, Governor of West Bengal, Minister for Home Affairs of the Indian Union and Chief Minister of Madras state. He was the founder of the Swatantra Party and the first recipient of India’s highest civilian award, the Bharat Ratna. Rajaji vehemently opposed the usage of nuclear weapons and was a proponent of world peace and disarmament. He was also nicknamed the Mango of Salem. In 1900 he started a prosperous legal practise. He entered politics and was a member and later President of Salem municipality. He joined the Indian National Congress and participated in the agitations against the Rowlatt Act, the Non-cooperation Movement, the Vaikom Satyagraha and the Civil Disobedience Movement. In 1930, he led the Vedaranyam Salt Satyagraha in response to the Dandi March and courted imprisonment. In 1937, Rajaji was elected Chief Minister or Premier An Illustrious Life 3 of Madras Presidency and served till 1940, when he resigned due to Britain’s declaration of war against Germany. He advocated cooperation over Britain’s war effort and opposed the Quit India Movement. He favoured talks with Jinnah and the Muslim League and proposed what later came to be known as the “C. -

Actors Acting Action

Actors Acting Action - c s Gopalkrishna Gandhi N a t io n a l In st it u t e o f A d v a n c ed St u d ies Indian Institute of Science Campus, Bangalore - 560 012, India Actors, Acting and Action Second Annual Mohandas Moses Memorial Lecture Gopalkrishna Gandhi Governor of West Bengal, Kolkata N IA S LEC T U R E L3 - 07 N a t io n a l Institute o f A d v a n c e d Studies Indian Institute of Science Campus Bangalore - 560 012, India © National Institute o f Advanced Studies 2007 Published by National Institute o f Advanced Studies Indian Institute o f Science Campus Bangalore - 560 012 Price: Rs. 65/- Copies of this report can be ordered from: The Head, Administration National Institute o f Advanced Studies Indian Institute o f Science Campus Bangalore - 560 012 Phone: 080-2218 5000 Fax: 080-2218 5028 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN 81-87663-72-3 lypeset & Printed by Aditi Enterprises #17/6, 22nd Cross, Bhuvaneshwari Nagar Magadi Road, Bangalore - 560 023 Mob: 92434 05168 Actors, Acting and Action’ Gopalkrishna Gandhi I thank the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Dr. Kasturirangan and Smt. Achala Mohandas Moses for their gracious invitation to me. I did not know Mohandas Moses personally. One does not have to know a man or woman of action to feel the impact of their work. I offer his memory my tribute; I offer his example my salutation. But I do so as chaff might, to grain. -

Current Affairs October 2019

LEGEND MAGAZINE (OCTOBER - 2019) Current Affairs and Quiz, English Vocabulary & Simplification Exclusively prepared for RACE students Issue: 23 | Page : 40 | Topic : Legend of OCTOBER | Price: Not for Sale OCTOBER CURRENT AFFAIRS the two cities from four hours to 45 minutes, once ➢ Prime Minister was speaking at a 'Swachh completed and will also decongest Delhi. Bharat Diwas' programme in Ahmedabad on ➢ As much as 8,346 crore is likely to be spent the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi. NATIONAL NEWS on the project, which was signed in March, 2016. ➢ Mr Modi said, the Centre plans to spend 3 lakh crore rupees on the ambitious "Jal Jivan PM addresses Arogya Manthan marking one Raksha Mantri Excellence Awards for Mission" aimed at water conservation. year of Ayushman Bharat; employees of Defence Accounts Department ➢ Prime Minister also released Launches a new mobile application for was given on its annual day. commemorative 150 rupees coins to mark the Ayushman Bharat ➢ Defence Accounts Department, one of the occasion ➢ Prime Minister Narendra Modi will preside over oldest Departments under Government of India, Nationwide “Paryatan Parv 2019” to the valedictory function of Arogya Manthan in is going to celebrate its annual day on October 1. promote tourism to be inaugurated in New New Delhi a two-day event organized by the ➢ Rajnath Singh will be Chief Guest at the Delhi National Health Authority to mark the completion celebrations, which will take place at Manekshaw ➢ The nationwide Paryatan Parv, 2019 to of one year of Ayushman Bharat, Pradhan Centre in Delhi Cantt. Shripad Naik will be the promote tourism to be inaugurated in New Delhi. -

Accidental Prime Minister

THE ACCIDENTAL PRIME MINISTER THE ACCIDENTAL PRIME MINISTER THE MAKING AND UNMAKING OF MANMOHAN SINGH SANJAYA BARU VIKING Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Group (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Offi ce Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offi ces: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England First published in Viking by Penguin Books India 2014 Copyright © Sanjaya Baru 2014 All rights reserved 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him which have been verifi ed to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. ISBN 9780670086740 Typeset in Bembo by R. Ajith Kumar, New Delhi Printed at Thomson Press India Ltd, New Delhi This book is sold subject to the condition that -

College Profile

TRAINING AND PLACEMENT OFFICE UNIVERSITY VISVESVARAYA COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING (UVCE) (Est.: 1917) BANGALORE UNIVERSITY, K.R.CIRCLE, BENGALURU - 560 001 Greetings from UVCE!! We are privileged to inform that UVCE has celebrated 100 successful years and counting. We are happy to invite your esteemed organization to visit our campus for recruitment to hire best of the talents for the academic year 2020-21. We await a positive response from your end and will be happy to answer any queries. A brief information about our institution is given below. HISTORY In 1917, the then Diwan of Mysore Sir M. Visvesvaraya felt a need to have an engineering college in the state, as the Civil Engineering College at Madras and College of Engineering at Poona were unable to accommodate enough students from the then Mysore State. He started the college in 1917 in Bangalore under the University of Mysore. It was started as the School of Engineering with 20 students each in Civil and Mechanical Engineering branches. It was the fifth engineering college to be started in India and the first one in Mysore State. In 1965, the name of the college was changed to University Visvesvaraya College of Engineering after its founder. It is currently the only constituent college of Bangalore University. The name UVCE is very popular in the field of technical education in Karnataka. In its existence of 103 years, the college has a history of great reputation and countless number of alumni. It has produced many eminent engineers, who have occupied coveted positions in industries, research labs and various prestigious institutions in India and abroad. -

From Dorota Borowa's Ice Painting Workshop. TABLE of CONTENTS

15.12.19 - 30.01.20 SUB MERGE From Dorota Borowa's Ice Painting workshop. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT SUBMERGE 4 OVERVIEW 6 THEMES AT SUBMERGE 12 CURATED PROGRAMMES AT SUBMERGE - CONFLUENCE 136 - SOAK 168 MEDIATORS 192 TAKE IT FURTHER 196 COLLABORATORS 202 *Please note that the images used throughout the report are the copyright of the photographer or Science Gallery Bengaluru and are not available under Creative Commons People and Water by T. S. Satyan and Jyoti Bhatt. Courtesy of Museum of Art and Photography (MAP). ABOUT SUBMERGE On 15 December 2019, we opened our first exhibition season on water, SUBMERGE, to the public. Through this exhibition, we supported the Year of Water initiative as observed by the Government of Karnataka. It also featured H2O Today, a popular traveling exhibition by the Smithsonian Institution. We encouraged visitors to explore the collective experiences of water and refIect on future challenges through a range of dynamic exhibits and workshops. We presented 15 exhibits spread across three floors of Bangalore International Centre, which examined the role of water in our lives, beyond the value that we derive from it. These exhibits were brought to life through 45 connected programmes such as workshops, lectures, master classes, film screenings and musical performances. Participants engaged with the latest research and thinking on water, and examined its cultural significance, by interacting with scholars and artists from around the world. We also provoked them to begin a dialogue on water as an urgent concern for the city of Bengaluru, and global challenge of the Anthropocene. Ice Painting by Dorota Borowa. -

Special Bulletin Remembering Mahatma Gandhi

Special Bulletin Remembering Mahatma Gandhi Dear Members and Well Wishers Let me convey, on behalf of the Council of the Asiatic Society, our greetings and good wishes to everybody on the eve of the ensuing festivals in different parts of the country. I take this opportunity to share with you the fact that as per the existing convention Ordinary Monthly Meeting of the members is not held for two months, namely October and November. Eventually, the Monthly Bulletin of the Society is also not published and circulated. But this year being the beginning of 150 years of Birth Anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, the whole nation is up on its toes to celebrate the occasion in the most befitting manner. The Government of India has taken major initiatives to commemorate this eventful moment through its different ministries. As a consequence, the Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India, has followed it up with directives to various departments and institutions-attached, subordinate, all autonomous bodies including the Asiatic Society, under its control for taking up numerous academic programmes. The Asiatic Society being the oldest premier institution of learning in whole of this continent, which has already been declared as an Institution of National Importance since 1984 by an Act of the Parliament, Govt. of India, has committed itself to organise a number of programmes throughout the year. These programmes Include (i) holding of a National Seminar with leading academicians who have been engaged in the cultivation broadly on the life and activities (including the basic philosophical tenets) of Mahatma Gandhi, (ii) reprinting of a book entitled Studies in Gandhism (1940) written and published by late Professor Nirmal Kumar Bose (1901-1972), and (iii) organizing a series of monthly lectures for coming one year. -

Current Affairs 2013- January International

Current Affairs 2013- January International The Fourth Meeting of ASEAN and India Tourism Minister was held in Vientiane, Lao PDR on 21 January, in conjunction with the ASEAN Tourism Forum 2013. The Meeting was jointly co-chaired by Union Tourism Minister K.Chiranjeevi and Prof. Dr. Bosengkham Vongdara, Minister of Information, Culture and Tourism, Lao PDR. Both the Ministers signed the Protocol to amend the Memorandum of Understanding between ASEAN and India on Strengthening Tourism Cooperation, which would further strengthen the tourism collaboration between ASEAN and Indian national tourism organisations. The main objective of this Protocol is to amend the MoU to protect and safeguard the rights and interests of the parties with respect to national security, national and public interest or public order, protection of intellectual property rights, confidentiality and secrecy of documents, information and data. Both the Ministers welcomed the adoption of the Vision Statement of the ASEAN-India Commemorative Summit held on 20 December 2012 in New Delhi, India, particularly on enhancing the ASEAN Connectivity through supporting the implementation of the Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity. The Ministers also supported the close collaboration of ASEAN and India to enhance air, sea and land connectivity within ASEAN and between ASEAN and India through ASEAN-India connectivity project. In further promoting tourism exchange between ASEAN and India, the Ministers agreed to launch the ASEAN-India tourism website (www.indiaasean.org) as a platform to jointly promote tourism destinations, sharing basic information about ASEAN Member States and India and a visitor guide. The Russian Navy on 20 January, has begun its biggest war games in the high seas in decades that will include manoeuvres off the shores of Syria. -

A Comparative Analysis of Educational Philosophy of Sri Aurobindo and J

Horizons of Holistic Education p ISSN : 2349-8811 July-September-2020, 7 (3), 166-178 eISSN : 2349-9133 A Comparative Analysis of Educational Philosophy Of Sri Aurobindo And J. Krishnamurty & Its Implications Dr. Rucha Desai Assistant Professor – Naranlala Institute of Teacher Education, Navsari, Gujarat. [email protected] Received: 27-06-2020 Accepted: 01-08-2020 ABSTRACT Philosophy and Education both are incomplete without each other. Education is the practical side of philosophy or conversely philosophy is the theory of education. A philosophy of education is a set of beliefs about education as to what should be done in education and what the outcome of education should be. Anyone who wishes to make educational decisions ought to have a philosophy of education. As Fitzgibbons notes, educational philosophy usually contains two distinct kinds of beliefs, namely (i) Empirical beliefs (ii) Philosophical beliefs. Indian education system as such it is practiced so far is mainly based on western philosophy. However, in our own country quite a number of enlightened people have given vent to their thoughts with respect to the type of education system that suits India. Among them the prominent thinkers include Swami Vivekananda, Sri Aurobindo, Rabindranath Tagore, Gandhiji, Annie Besent and J. Krishnamurti. Almost all of them had a holistic view of education which suited the Indian condition. So here an attempt has been made to compare the Educational Philosophy of Aurobindo and J.Krishnamurty to present their views, philosophy, and principles of teaching, aims of education and its implications. Key Words: Education, Philosophy of Education, Empirical beliefs, hhe.cugujarat.ac.in 156 HORIZONS OF HOLISTIC EDUCATION, July-September-2020, 7 (3), 166-178 INTRODUCTION Among them the prominent thinkers include Swami Vivekananda, Sri Aurobindo, Education, like all conscious and deliberate Rabindranath Tagore, Gandhiji, Annie action, seeks for a basis of demonstrated Besent and J. -

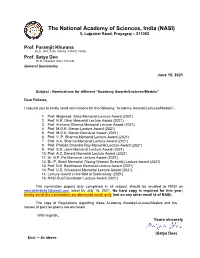

Nominations for Different “Academy Awards/Lectures/ Medals”

The National Academy of Sciences, India (NASI) 5, Lajpatrai Road, Prayagraj – 211002 Prof. Paramjit Khurana Ph.D., FNA, FASc, FNAAS, FTWAS, FNASc Prof. Satya Deo Ph.D. (Arkansas, USA), F.N.A.Sc. General Secretaries June 15, 2021 Subject : Nominations for different “Academy Awards/Lectures/Medals” Dear Fellows, I request you to kindly send nominations for the following “Academy Awards/Lectures/Medals”– 1. Prof. Meghnad Saha Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 2. Prof. N.R. Dhar Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 3. Prof. Archana Sharma Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 4. Prof. M.G.K. Menon Lecture Award (2021) 5. Prof. M.G.K. Menon Memorial Award (2021) 6. Prof. V. P. Sharma Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 7. Prof. A.K. Sharma Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 8. Prof. Prafulla Chandra Ray Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 9. Prof. S.K. Joshi Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 10. Prof. A.C. Banerji Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 11. Dr. B.P. Pal Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 12. Dr. P. Sheel Memorial (Young Women Scientist) Lecture Award (2021) 13. Prof. B.K. Bachhawat Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 14. Prof. U.S. Srivastava Memorial Lecture Award (2021) 15. Lecture Award in the field of Biodiversity (2021) 16. NASI-Buti Foundation Lecture Award (2021) The nomination papers duly completed in all respect should be emailed to NASI on [email protected] latest by July 15, 2021. No hard copy is required for this year; kindly send the nomination on aforesaid email only (not on any other email id of NASI). The copy of Regulations regarding these Academy Awards/Lectures/Medals and the names of past recipients are enclosed. -

The Crux of the Hindu and PIB Vol 36

News for August 2017aspirantforum.com Hindu and PIB Crux Vol. 36 NewsVol. and 36 Events of August 2017 aspirantforum.com Vol. 36 Aug 2017 36 Aug Vol. Visit Aspirantforum.com for guidance and study material for IAS Exam. aspirantforum.com Hindu and PIB Crux Vol. 36 News and Events of August 2017 Aspirant Forum is a Community for the UPSC Contents Civil Services (IAS) Aspirants, to discuss and debate the various things related to the exam. We welcome an active National News.............4 participation from the fellow members to enrich the knowledge of all. Economy News..........22 Editorial Team: PIB Compilation: Nikhil Gupta International News....36 The Hindu Compilation: Shakeel Anwar India and the World..46 Ranjan Kumar Shahid Sarwar Karuna Thakur Science and Technology + Designed by: Anupam Rastogi Environment..............53 The Crux will be published online Miscellaneous News and for free on 10th of every month. We appreciate the friends and Events.........................73 followers for apprepreciating our effort. For any queries, guidance needs and support, Please contact at: [email protected] You may also follow our website Aspirantforum.com for free on- line coaching and guidanceforIASaspirantforum.com Vol. 36 Aug 2017 36 Aug Vol. Visit Aspirantforum.com for guidance and study material for IAS Exam. aspirantforum.com Hindu and PIB Crux Vol. 36 News and Events of August 2017 About the ‘CRUX’ Introducing a new and convenient product, to help the aspirants for the various public services examina- tions. The knowledge of the Current Affairs constitute an indispensable tool for all the recruitment examinations today.However, an aspirant often finds it difficult to read and memorize all the current affairs, from an exam perspective.The Newspapers and magazines are full of information, that may or may not be useful for the exams. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita