Geographic Features of the Coos Estuary and Lower Coos Watershed Summary: the Coos Estuary Is the Second Largest Estuary in Oregon, and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lost in Coos

LOST IN COOS “Heroic Deeds and Thilling Adventures” of Searches and Rescues on Coos River Coos County, Oregon 1871 to 2000 by Lionel Youst Golden Falls Publishing LOST IN COOS Other books by Lionel Youst Above the Falls, 1992 She’s Tricky Like Coyote, 1997 with William R. Seaburg, Coquelle Thompson, Athabaskan Witness, 2002 She’s Tricky Like Coyote, (paper) 2002 Above the Falls, revised second edition, 2003 Sawdust in the Western Woods, 2009 Cover photo, Army C-46D aircraft crashed near Pheasant Creek, Douglas County – above the Golden and Silver Falls, Coos County, November 26, 1945. Photo furnished by Alice Allen. Colorized at South Coast Printing, Coos Bay. Full story in Chapter 4, pp 35-57. Quoted phrase in the subtitle is from the subtitle of Pioneer History of Coos and Curry Counties, by Orville Dodge (Salem, OR: Capital Printing Co., 1898). LOST IN COOS “Heroic Deeds and Thrilling Adventures” of Searches and Rescues on Coos River, Coos County, Oregon 1871 to 2000 by Lionel Youst Including material by Ondine Eaton, Sharren Dalke, and Simon Bolivar Cathcart Golden Falls Publishing Allegany, Oregon Golden Falls Publishing, Allegany, Oregon © 2011 by Lionel Youst 2nd impression Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-9726226-3-2 (pbk) Frontier and Pioneer Life – Oregon – Coos County – Douglas County Wilderness Survival, case studies Library of Congress cataloging data HV6762 Dewey Decimal cataloging data 363 Youst, Lionel D., 1934 - Lost in Coos Includes index, maps, bibliography, & photographs To contact the publisher Printed at Portland State Bookstore’s Lionel Youst Odin Ink 12445 Hwy 241 1715 SW 5th Ave Coos Bay, OR 97420 Portland, OR 97201 www.youst.com for copies: [email protected] (503) 226-2631 ext 230 To Desmond and Everett How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it. -

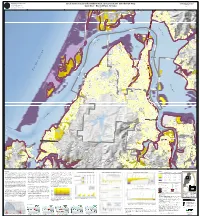

Tsunami Inundation Map for Coos

G E O L O G Y F A N O D STATE OF OREGON T Tsunami Inundation Map Coos-05 N M I E N DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES M E T R R A Tsunami Inundation Maps for Coos Bay - North Bend, A www. OregonGeology.org L Local Source (Cascadia Subduction Zone) Tsunami Inundation Map P I E Coos County, Oregon N D D Larry Givens, Governing Board Chair U N S O T Vicki S. McConnell, Director and State Geologist G R E Plate 1 I R E S O Don WT. Lewis, Assistant Director Coos Bay - North Bend, Oregon Rachel R. Lyles Smith, Project Operations Manager 2012 1937 Ian P. Madin, Chief Scientist 124°20'0"W 124°18'0"W 124°16'0"W 124°14'0"W 124°12'0"W L N TRANS-PACIFIC LN I C I F C A R O B I N R D - P 43°26'0"N S N D A R R T E V O C N N N L A D D OV E R W O J 100 S W A L L O W R D E A ! S T B A Y R D North Bay RFPD M Jordan A L L A R D L N Cove 43°26'0"N ¤£101 R O S E M T N L N 100 C o o 25 City of North Bend "7 s E . C . R D B "5 M C C L U R G L N 200 a 100 y 25 EAST BAY RD y L N E E City of North Bend S a R U O B C City of Coos Bay G O L F D s F E R R Y R o ¤£101 E V C A A o City of Coos Bay R L S O R R N P 25 H O R T S I S 100 M C N L I N A R I O North W R Pony E S P V E E A O Bend A I R R ! L P 100 T Fire N O Slough W R SHERMAN AVE T W E I L A V N Y Y A B 200 L O O P C O L O R A D O A V E O O D City of North Bend A R B AY S T O M L A O P C L E L E A F F S T F L O R I D A A V E M A P L E S T H AY E S S T A R T H U R S T J O H N S O N S T M O N TA N A A V E D C O N N E C T I C U T A V E T R S ¤£101 L L W E D A X A M E MCPHERSON AVE H U N I O N A V E L -

Coos Bay BCS Number: 47-8

Coos Bay BCS number: 47-8 ***NOTE: The completion of this site description is still in progress by our Primary Contact (listed below). However, if you would like to contribute additional information to this description, please contact the Klamath Bird Observatory at [email protected]. Site description author(s) Jennifer Powers Danielle Morris, Research and Monitoring Team, Klamath Bird Observatory Primary contact for this site Mike Graybill, South Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve Manager. Telephone: 541-888-5558 ext. 24, e-mail: [email protected]. Site location (UTM) Datum: NAD83, Zone: 10, Easting: 394143, Northing: 4802686 General description The Coos Bay estuary covers 54 square miles of open channels and tide flats located near the towns of the Coos Bay and North Bend on the southern Oregon coast. The estuary ranges between a mile and a mile and a half wide. A 42 ft. deep, sixteen-mile long ship channel is maintained from the harbor entrance to the Port of Coos Bay. Numerous slough systems and freshwater channels flow into Coos Bay. The narrow estuary is maintained at its mouth by two rock jetties extending from North Spit on the north and Coos Head on the south. From the harbor entrance the main channel bears northward past the communities of Charleston, Barview and Empire, then east around the city of North Bend, and south past downtown Coos Bay. At Coos Bay the channel bears east to the mouth of the Coos River. About two miles upstream the river divides into the Millicoma River on the left and the South Fork of the Coos River on the right. -

AN INVENTORY of MARITIME ANTIQUES and RELICS of the COOS BAY AREA REFLECTIONS of a SOMETIMES FORGOTTEN PAST by Gail E. Curtis Or

AN INVENTORY OF MARITIME ANTIQUES AND RELICS OF THE COOS BAY AREA REFLECTIONS OF A SOMETIMES FORGOTTEN PAST By Gail E. Curtis Oregon Institute of Marine Biology Summer, 1975 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ,INTRODUCTION 1 - EXPLANATIONS AND ABBREVIATIONS 6 BACKGROUND INFORMATION OF THE INVENTORIED COLLECTIONS 7 MARITIME ANTIQUES AND RELICS 17 BOAT NAME PLATES 28 HALF MODELS 29 MARITIME LITERATURE 31 MARITIME MAPS, CHARTS, AND DRAWINGS 35 MARITIME PHOTOGRAPHS 39 LIFE SAVING STATION General History 75 LIFES SAVINGS CREW, STATION AND EQUIPMENT PHOTOGRAPHS.. 76 CAPE ARAGO LIGHTHOUSE PHOTOGRAPHS 78 JETTY CONSTRUCTIONS PHOTOGRAPHS BO EARLY MARSHFIELD PHOTOGRAPHS 83 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS Victor West 87 BIBLIOGRAPHY 92 DISTRIBUTION LIST 93 INTRODUCTION Coos Bay has always been tied to the sea. From the rich estuarys earliest settlement in the 1830s, its lines of supply Ind communication have been with the sea rather than the hinter- land across the Coast Range Mountains. Even as late as 1915 when the railroad came to southwestern Dregon, the sea, the bay, and the rivers of the Coos Bay region represented the main forms of coastwise trade with California and the inter-community trade from the farms and lumber camps of the interior to the urban market areas of Marshfield (Coos Bay) and later North Bend. In some respects,modern Coos Bay remains even more tied to the sea than in the past. Emerging as a major port of international trade, mainly through the export of its forest products, Coos Bays leaders recognize their communitys future fortune lies with the sea, for a form of transportation, an important food supply, and a desirable periphery for a living environment. -

Above the Falls

Revised, Second Edition Revised, Second Edition ABOVE THE FALLS Second Edition Joe Schapers’ homestead on Upper Glenn Creek, 1913 ABOVE THE FALLS Second Edition An Oral and Folk History of Upper Glenn Creek, Coos County, Oregon by Lionel Youst Including tape-recorded interviews, narratives, and other material by Alice Wilkinson Allen, Warren Browning, Belle Leaton Clarke, Hattie Leaton Cotter, Helen Cummings, Lillian Austin Edgehill, Wilma Leaton Hoellig, Allen Lively, Charles Middleton, Robert Milton, Erma Ott, Harold Ott, Jerry Phillips, Elwin Saling, Franklyn E. Smith, Marvin Stemmerman, Patricia Wilkinson, and George Youst. Written at Allegany, Oregon, September 1991 to September 1992, with revisions based on material received between 1992 and 2003. Golden Falls Publishing Allegany, Oregon Golden Falls Publishing, Allegany, Oregon © 2003 by Lionel Youst All rights reserved. First edition 1992 Second edition 2003 First impression 2003 Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-9726226-0-8 ISBN 0-9726226-1-6 (pbk.) Library of Congress cataloging data: F882.C7 Dewey Decimal cataloging data: 979.523 Youst, Lionel D., 1934 - Above The Falls, Second Edition Includes index, maps, bibliography, & photographs Frontier and Pioneer Life – Oregon – Coos County Logging – Oregon – Coos County – History Lumber Trade – Oregon – Coos County – History Coos County, Oregon – History Quotations at the beginning of each of the major parts of this book are from Rethinking Home: A Case for Writing Local History, by Joseph A. Amato, University of California Press (2002). They are used here with permission from the Regents of the University of California. Passages from A Century of Coos and Curry, by Peterson and Powers (1952), and Glancing Back (1972) are used with permission from the Coos County Historical Society. -

Inventory of Fall Chinook Spawning Habitat in Mainstem Reaches of Oregon's Coastal Rivers

Inventory of Fall Chinook Spawning Habitat in Mainstem Reaches of Oregon's Coastal Rivers CUMULATIVE REPORT for work conducted pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award Numbers: 1999 – 2000: NA97FP0310 2000 - 2001: NA07FP0383 and U.S. Section, Chinook Technical Committee Project Numbers: N99-12 and C00-09 Brian Riggers Kris Tempel Steve Jacobs Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Coastal Salmonid Inventory Project Coastal Chinook Research and Monitoring Project Corvallis & Newport, OR June 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS STUDY AREA ......................................................................................1 METHODS............................................................................................3 SURVEY TARGETS................................................................................................ 3 CRITERIA FOR IDENTIFYING SPAWNING HABITAT ..................................................... 3 POOLS ................................................................................................................ 5 SURVEY PROCEDURE ........................................................................................... 5 VERIFICATION SURVEYS ....................................................................................... 6 RESULTS.............................................................................................6 DISCUSSION .....................................................................................18 RECOMMENDATIONS......................................................................19 -

Bandon Hatchery

BANDON HATCHERY PROGRAM MANAGEMENT PLAN 2020 Bandon Hatchery (Beaver Creek, Big Creek Pond, Blossom, Charleston, Cunningham Creek, Coquille, Eel Creek, Ferry Creek, Hodges, Laverne Park, Millicoma Pond, Morgan Creek, Noble Creek, Saunders, Sevenmile Creek, Tenmile and Woodward Creek Acclimation Sites) INTRODUCTION Bandon Hatchery is located one mile east of the City of Bandon. The site is at an elevation of approximately 98 feet above sea level, at latitude 43.1161 and longitude -124.3842. Total land area is 32.7 acres. The hatchery water supply is obtained from two sources: Ferry Creek and Geiger Creek. Water from both sources is supplied by gravity. Starting on October 13, 2017, 3.5 cfs was transferred to the hatchery in which 2.5 was dedicated for fish production and 1 cfs for instream rights. This now gives the hatchery a combined total of 5.5 cfs. The facility is staffed with 3.0 FTE's. Rearing Facilities at Bandon Hatchery Unit Unit Unit Unit Unit Number Total Construction Type Length Width Depth Volume Units Volume Material Age Condition Comment (ft) (ft) (ft) (ft3) (ft3) Adult Holding Pond 80 20 3.25 5200 1 5200 concrete 1950 poor spawning building built over first 20' of pond Raceway 120 20 3.5 8400 1 8400 concrete 1950 fair Raceway 110 20 3.67 8074 1 8074 concrete 1950 fair Raceway 50 20 5.5 5500 1 5500 concrete 1937 poor used for settling pond for vacuum sludge Raceway 45 15 2.5 1688 1 1688 concrete 1950 good Raceway 100 20 3.5 7000 1 7000 concrete 1950 poor used as acclimation ponds Raceways 100 20 3.5 7000 2 14000 concrete 1958 good Troughs 16 3.2 2 102 2 205 concrete 1958 fair Troughs 16.75’ 2.2 3 110.55 2 221.1 fiberglass 2018 excellent Troughs 16 2.5 1.33 53 4 213 fiberglass 1991 good Vertical incubators 448 2003 excellent 28 stacks of 16 trays PURPOSE Bandon Hatchery was constructed in 1925 and facility operations are funded by the State of Oregon. -

Raised Marine Features, Radiocarbon Dates, and Sea Level Changes, Eastern Melville Peninsula, Arctic Canada’ L.A

ARCTIC VOL. 44, NO. 1 (MARCH 1991) R 63-73 Raised Marine Features, Radiocarbon Dates, and Sea Level Changes, Eastern Melville Peninsula, Arctic Canada’ L.A. DREDGE2 (Received 5 April 1990; accepted in revised form 9 October 1990) ABSTRACT. Radiocarbon dates from eastern Melville Peninsula indicatethat deglaciation of western Foxe Basin occurredabout 6900 years ago, although lateice persisted in an area northwest of Hall Lake and on the central plateau. Relative sea level was as high as 144 m above present at that time. ’ho new well-controlled sea level curves depict emergence as an exponential decay function. Marine limit elevations and nested curves indicate a major ice-loading centre in south-central Foxe Basin. Thesedata and archaeological dates suggest a secondary recent rebound centre in the northern part of the basin. Flights of raised beaches, prevalentin the area, are composed of angular limestone fragments and suggest that frost-riving occurs in shallow foreshore environments. The prominentwash line near the marine limit suggests that Foxe Basin had less sea ice cover prior to 6OOO years ago but that coastal processes have been similar to present since that time. Key words: Arctic, coasts, archaeology, radiocarbon dating, glacial history, emergence, sea level, geomorphology RESUMl?. Des datations au carbone radioactif dansla presqu’ile Melville orientale indiquent que la dbglaciation du Foxe bassin s’est produit vers 6900 ans, bien quela glace ait persist6 dans une zone situ& au nord-ouest du Lac etHall sur le plateau central.A cette bpoque, le niveau de la mer s’tlevait A 144 m au-dessus du niveau actuel. -

Index of Surface-Water Records to September 30, 1970 Part 14.-Pacific Slope Basins in Oregon and Lower Columbia River Basin

Index of Surface-Water Records to September 30, 1970 Part 14.-Pacific Slope Basins in Oregon and Lower Columbia River Basin GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 664 Index of Surface-Water Records to September 30, 1970 Part 14.-Pacific Slope Basins in Oregon and lower Columbia River Basir GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 664 Washington 1971 United States Department of the Interior ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secnetory Geological Survey W. A. Radlinski, Acting Director Free on applteohon to ,;,. U.S GeoiCJ91Cal Sur-..y, Wosh~ngt.n, D .. C 20242 Index of Surface-Water Records to September 30, 1970 Part 14.-Pacific Slope Basins in Oregon and Lower Columbia River Basin INTRODUCTION This report lists the streamflow and res~rvoir stations in the Pacific slope basins in Oregon and lower Columbia River basin for which records have been or are to be published in reports of the Geological Survey for periods through September 30, 1970. It supersedes Geological Survey Circular 584, It was updated by personnel of the Data Reports Unit, Water Resources Division, Geological Survey. Basic data on surface-water supply have been published in an annual series of water-supply papers consisting of several volumes, including one each for the States of Alaska and Hawaii. The area of the other 48 States is divided into 14 parts whose boundaries coincide with certain natural drainage lines. Prior to 1951, the records hr the 48 States were published inl4volumes,oneforeachof the parts, From 1951 to 1960, the records for the 48 States were published annually in 18 volumes, there being 2 volumes each for Parts 1, 2, 3, and 6, Beginning in 1961, the annual series of water-supply papers on surface-water supply was changed to 2. -

Coos River Fall Chinook Salmon Program

HATCHERY AND GENETIC MANAGEMENT PLAN (HGMP) Hatchery Program: Coos River Fall Chinook Program Species or Fall Chinook Salmon (Stock 37) Hatchery Stock: Agency/Operator: Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Watershed and Region: Coos Watershed – ODFW West Region Date Submitted: October 19, 2005 First Update Submitted: December 8, 2008 Second Update Submitted: November 12, 2014 Third Update Submitted: June 6, 2016 Fourth Update Submitted: September 20, 2017 Date Last Updated: September 20, 2017 Coos River fall Chinook HGMP 2017 1 SECTION 1. GENERAL PROGRAM DESCRIPTION 1.1) Name of hatchery or program. Coos River Fall Chinook Program 1.2) Species and population (or stock) under propagation, and ESA status. Oregon coastal fall Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) –Stock 37 ESA status: The wild and hatchery-produced fall Chinook of the Coos River and Oregon coast are not ESA-listed (Federal Register Notice 1998). 1.3) Responsible organization and individuals. Lead Contact: Name (and title): Scott Patterson, Fish Propagation Program Manager Agency: Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Address: 4034 Fairview Industrial Drive SE, Salem, OR 97302 Telephone: (503) 947-6218 Fax: (503) 947-6202 Email: [email protected] Onsite Lead Contact: Name (and title): Michael Gray, District Fish Biologist Agency: Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Address: 63538 Boat Basin Drive, Charleston, OR 97420 Telephone: (541) 888-5515 Fax: (541) 888-6860 Email: [email protected] Hatchery Contact: Name (and title): David Welch, Bandon Hatchery Manager Agency: Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Address: 55198 Fish Hatchery Rd., Bandon, OR 97411 Telephone: (541) 347-4278 Fax: (541) 347-3079 Email: [email protected] Other agencies, Tribes, co-operators, or organizations involved, including contractors, and extent of involvement in the program. -

An Eye on Central America U.S

An Eye on Central America U.S. GOVERNMENTWORLD ™ GEOGRAPHYHISTORY from the Esri GeoInquiries collection for World Geography Target audience – World geography learners Time required – 15 minutes Activity Explore the physical geography and people of Central America. Social studies C3:D2.Geo.5.6-8. Analyze the combinations of cultural and environmental characteris- standards tics that make places both similar to and different from other places. C3:D2.Geo.2.6-8. Use maps, satellite images, photographs, and other representations to explain relationships between the locations of places and regions and the changes in their environmental characteristics. Learning Outcomes • Follow the development and impact of a major hurricane. • Integrate satellite imagery of a hurricane with a plot of the hurricane’s path. Map URL: http://esriurl.com/worldGeoInquiry13 Ask Central America comprises what geographic landform? ʅ Click the link above to launch the map. ʅ With the Details button underlined, click the button, Show Contents.. – There are several definitions of which countries compose Central America. This inquiry considers the seven countries south of Mexico. – An isthmus is a narrow strip of land with sea on either side, forming a link between two larger areas of land. ? Why are Central American countries an isthmus? [They connect the large land mass of Mexico (north) and South America (south), the Caribbean Sea (east), and the Pacific Ocean (west).] Acquire What are the physical characteristics of Central America? ʅ Click the button, Bookmarks. Select Central America. (See the ToolTip on the next page for details.) ? Which countries make up Central America? [Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Belize] ʅ Check the box left of the layer name, Holocene Volcanoes. -

Coos County Flood Insurance Study, P14216.AO, Scales 1:12,000 and 1:24,000, Portland, Oregon, September 1980

FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY COOS COUNTY, OREGON AND INCORPORATED AREAS COMMUNITY COMMUNITY NAME NUMBER BANDON, CITY OF 410043 COOS BAY, CITY OF 410044 COOS COUNTY (UNINCORPORATED AREAS) 410042 COQUILLE, CITY OF 410045 LAKESIDE, CITY OF 410278 MYRTLE POINT, CITY OF 410047 NORTH BEND, CITY OF 410048 POWERS, CITY OF 410049 Revised: March 17, 2014 Federal Emergency Management Agency FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 41011CV000B NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) report may not contain all data available within the Community Map Repository. Please contact the Community Map Repository for any additional data. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) may revise and republish part or all of this FIS report at any time. In addition, FEMA may revise part of this FIS report by the Letter of Map Revision process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS report. Therefore, users should consult with community officials and check the Community Map Repository to obtain the most current FIS report components. Initial Countywide FIS Effective Date: September 25, 2009 Revised Countywide FIS Date: March 17, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Purpose of Study ............................................................................................................