Chapter Three

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete 230 Fellranger Tick List A

THE LAKE DISTRICT FELLS – PAGE 1 A-F CICERONE Fell name Height Volume Date completed Fell name Height Volume Date completed Allen Crags 784m/2572ft Borrowdale Brock Crags 561m/1841ft Mardale and the Far East Angletarn Pikes 567m/1860ft Mardale and the Far East Broom Fell 511m/1676ft Keswick and the North Ard Crags 581m/1906ft Buttermere Buckbarrow (Corney Fell) 549m/1801ft Coniston Armboth Fell 479m/1572ft Borrowdale Buckbarrow (Wast Water) 430m/1411ft Wasdale Arnison Crag 434m/1424ft Patterdale Calf Crag 537m/1762ft Langdale Arthur’s Pike 533m/1749ft Mardale and the Far East Carl Side 746m/2448ft Keswick and the North Bakestall 673m/2208ft Keswick and the North Carrock Fell 662m/2172ft Keswick and the North Bannerdale Crags 683m/2241ft Keswick and the North Castle Crag 290m/951ft Borrowdale Barf 468m/1535ft Keswick and the North Catbells 451m/1480ft Borrowdale Barrow 456m/1496ft Buttermere Catstycam 890m/2920ft Patterdale Base Brown 646m/2119ft Borrowdale Caudale Moor 764m/2507ft Mardale and the Far East Beda Fell 509m/1670ft Mardale and the Far East Causey Pike 637m/2090ft Buttermere Bell Crags 558m/1831ft Borrowdale Caw 529m/1736ft Coniston Binsey 447m/1467ft Keswick and the North Caw Fell 697m/2287ft Wasdale Birkhouse Moor 718m/2356ft Patterdale Clough Head 726m/2386ft Patterdale Birks 622m/2241ft Patterdale Cold Pike 701m/2300ft Langdale Black Combe 600m/1969ft Coniston Coniston Old Man 803m/2635ft Coniston Black Fell 323m/1060ft Coniston Crag Fell 523m/1716ft Wasdale Blake Fell 573m/1880ft Buttermere Crag Hill 839m/2753ft Buttermere -

Chapter Three

Chapter Three In 1906 Canon Rawnsley wrote a book entitled Months of the Lakes, which featured a chapter about Mardale and the hunt. Rawnsley didn’t’ like hunting but the following passage suggests either he actually went or interviewed someone who did, The following text is copied from the original. THE MARDALE SHEPHERDS' MEETING. There lies to the east of the great High Street range a little water flood the Roman soldiers looked on with delight, for it called them back to their own lakeland hills, but they looked on it too with awe, for its waters seemed as black as the Stygian lake they feared. Ages before the Romans ran their high street, this lake was cared for by the shepherd children of Neolithic times. Their camps, their burial grounds, their standing stones are with us on the fell sides that slope to this lake which we call Haweswater to-day. The Vikings gave it that name, for it means the Halse Water or Neck-Water, and the neck is the promontory that the Messand beck in lapse of centuries has made, that runs out from the north-west shore towards the Naddle forest, and so nearly divides the lake in two, that one end is called Low Water and the other High Water. An aerial view of the old lakes of Haweswater, notice the narrowing between high and low water, called the straits, the new road scar can be seen on the far side of the valley. One can get to the lake from Penrith up the Lowther valley or from Shap and Bampton, and when one has reached it one cannot linger by the shore if the sun is westering, for there is no house of call nearer than the Dun Bull, and this is a mile beyond Haweswater, beneath the Nan Bield Pass. -

Number in Series 10

THE JOURNAL OF THE Fell and Rock Climbing Club OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT. VOL. 4. NOVEMBER, 1916. No. 1. LIST OF OFFICERS. President: W. P. HASKETT-SMITH. Vice-President: H. B. LYON. Honorary Editor of Journal : WILLIAM T. PALMER, Beechwood, Kendal. Honorary Treasurer : ALAN CRAIG, B.A.I., Monkmoors, Eskmeals, R.S.O., Cumberland. Hon. Assistant Treasurer : (To whom all Subscriptions should be paid) WILSON BUTLER, Glebelands, Broughton-in-Furness. Honorary Secretary : DARWIN LEIGHTON, Cliff Terrace, Kendal. Honorary Librarian: J. P. ROGERS. Members of the Committee : H. F. HUNTLEY. L. HARDY. J. COULTON. W. ALLSUP. G. H. CHARTER. DR. J. MASON. H. P. CAIN. Honorary Members t WILLIAM CECIL SLINGSBY, F.R.G.S. W. P. HASKETT-SMITH, M.A. CHARLES PILKINGTON, J.P. PROF. J. NORMAN COLLIE, PH.D., F.R.S. GEOFFREY HASTINGS. PROF. L. R. WILBERFORCE, M.A. GEORGE D. ABRAHAM. CANON H. D. RAWNSLEY, M.A. GEORGE B. BRYANT. REV. J. NELSON BURROWS, M.A. GODFREY A. SOLLY. HERMANN WOOLLEY, F.R.G.S. RULES. l.—The Club shall b* called " THE TELL AND ROCK CLIMBING CLUB OF THE BHGLISH LAKE DMTRICT," and its objects shall be to encourage rock-climbing and fell-walking in the Lake District, to serve as a bond of union for all lovers of mountain-climbing, to enable its members to meet together in order to participate in these forms of sport, to arrange for meetings, to provide books, maps, etc., at the various centres, and to give information and advice on matters pertaining to local mountaineering and rock-climbing. -

Fell and Rock Climbing Club of the ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT

THE JOURNAL OF THE Fell and Rock Climbing Club OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT. VOL. 5. 1921. No. 3. LIST OF OFFICERS. President: GODFREY A. SOLLY. Vice-Presidents: C. H. OLIVERSON AND T. C. ORMISTON-CHANT. T. R. BURNETT. Honorary Editor of Journal : R. S. T. CHORLEY, 34 Cartwright Gardens, London, W.C.I. Honorary Treasurer: W. G. MILLIGAN, Hollin Garth, Barrow-in-Furness. Honorary Secretary : J. B. WILTON, 122 Ainslie Street, Barrow-in-Furness. Honorary Librarian : H. P. CAIN, Graystones, Ramsbottom, near Manchester. Auditors .- R. F. MILLER & Co., Barrow-in-Furness. Members of Committee : G. S. BOWER. T. H. SOMERVELL. W. BUTLER. A. WELLS. D. LEIGHTON. Miss E. F. HARLAND. P. R. MASSON. MRS. KELLY. I. P. ROGERS. Miss D. E. PILLEY. E. H. P. SCANTLEBURY. Honorary Members: VISCOUNT LECONFIELD. GEORGE D. ABRAHAM. GEORGE B. BRYANT. REV. J. NELSON BURROWS, M.A. PROF. J. NORMAN COLLIE. Ph.D., F.R.S. W. P. HASKETT-SMITH, M.A. GEOFFREY HASTINGS. HAROLD RAEBURN. WILLIAM CECIL SLINGSBY, F.R.G.S. GODFREY A. SOLLY. PROF. L. R. WILBERFORCE. M.A. GEOFFREY WINTHROP YOUNG. RULES. 1.—The Club shall be called "THE FELL AND ROCK CLIMBING CLUB OF THE ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT," and its objects shall be to encourage rock-climbing and fell walking in the Lake District, to serve as a bond of union for all lovers of mountain-climbing, to enable its members to meet together in order to participate in these forms of sport, to arrange for meetings, to provide books, maps, etc., at the various centres, and to give information and advice on matters pertaining to local mountaineering and rock-climbing. -

Complete the Wainwright's in 36 Walks - the Check List Thirty-Six Circular Walks Covering All the Peaks in Alfred Wainwright's Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells

Complete the Wainwright's in 36 Walks - The Check List Thirty-six circular walks covering all the peaks in Alfred Wainwright's Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells. This list is provided for those of you wishing to complete the Wainwright's in 36 walks. Simply tick off each mountain as completed when the task of climbing it has been accomplished. Mountain Book Walk Completed Arnison Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Birkhouse Moor The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Birks The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Catstye Cam The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Clough Head The Eastern Fells St John's Vale Skyline Dollywaggon Pike The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Dove Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Fairfield The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Glenridding Dodd The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Gowbarrow Fell The Eastern Fells Mell Fell Medley Great Dodd The Eastern Fells St John's Vale Skyline Great Mell Fell The Eastern Fells Mell Fell Medley Great Rigg The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Hart Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Hart Side The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Hartsop Above How The Eastern Fells Kirkstone and Dovedale Circuit Helvellyn The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Heron Pike The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Mountain Book Walk Completed High Hartsop Dodd The Eastern Fells Kirkstone and Dovedale Circuit High Pike (Scandale) The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Little Hart Crag -

Past and Present at the English Lakes Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

6 70 Qlnrnell Intu^rattQ library BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF fi^nrg m. Sage 1891 §306" PAST AND PRESENT AT THE ENGLISH LAKES PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW Publishtrs to tlu anibsrsity MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON New York The Macmillan Co. Toronto • The Macmillan Co. of Canada London • Sinipkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridge Bowes and Boiues Edinburgh Douglas and Foulis Sydney Angus and Robertson Past and Present at the English Lakes By the Rev. H. D. Rawnsley Canon of Carlisle Author of " Literary Associations of the English Lakes," etc. Glasgow James MacLehose and Sons Publishers to the University 1916 6 M^^Til GLASGOW : PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS BY ROBERT MACLRHOSE AND CO. LTD. ^^ n^ \' V. PREFATORY NOTE My thanks are due to those who have supplied the photographs for illustration. To Mr. Mayson for view from Helvellyn Top ; to Mr. Pettitt for Harter Fell and High Street from Mardale and for the Nag's Head, Wytheburn ; and to Mr. Abraham for the portrait of Mrs. Dixon. Specially must I thank Mrs. Jackson for allowing me to reproduce a photograph by Henry Mayson ot Keswick of the Old House of the Hechstetters. To Mr. F. C. Eeles for his photographs of the Consecration Crosses at Crosthwaite from which my wife made the drawing. To Mr. Ernest Coleridge for permission to have a photograph made of the portrait of Hartley Coleridge in his possession, which was painted the year before his death by William Bowness of Kendal, and which has been pronounced by those who remember the poet as a most excellent likeness. -

The 1938 Meet Saw for the First Time Sheep Taken by Road, Owing to The

Chapter Eleven Postscript: After the flooding, the Shepherds Meet continued, but at a different venue. The 1938 meet saw for the first time sheep taken by road, owing to the demolition of the Old Dun Bull hotel, the former meeting place, Manchester Corporation arranged for the shepherds and sheep to be taken to Bampton where that years meeting was held. The meet continued and still does to this day (2011) although the venue has changed from time to time. The shepherd’s meet still appears on the Ullswater Foxhounds fixture card and prior to the hunting ban in 2005 the valley echoed to the cry of hounds in pursuit of the fox, as they always had done. But with the demolition of the Dun Bull comes the end of our story of the Mardale Hunt, below are a few hunting reports from the later years. My family attended many meets before 1936 and after and the consensus of opinion was despite the best efforts of the organisers “it wasn’t the same anymore” Some Hunt Reports post 1936 The Ullswater completed the three week tour of their southern ground by going from Longsleddale to Bampton for the shepherds’ meet weekend, and on Saturday provided the first real jingle for years at the top end of Mardale. Anthony Barker loosed his hounds on Bransty, and before long their music was echoing across the lake which has gathered the thousand waters to its bosom to such an extent that hunters who have banished from the haunts of raven and fox during “Hitler’s years” stared amazed at the vast expanse. -

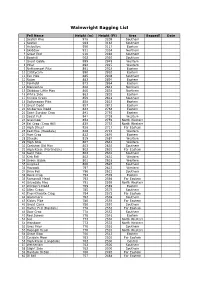

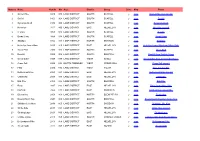

Wainwright Bagging List

Wainwright Bagging List Fell Name Height (m) Height (Ft) Area Bagged? Date 1 Scafell Pike 978 3209 Southern 2 Scafell 964 3163 Southern 3 Helvellyn 950 3117 Eastern 4 Skiddaw 931 3054 Northern 5 Great End 910 2986 Southern 6 Bowfell 902 2959 Southern 7 Great Gable 899 2949 Western 8 Pillar 892 2927 Western 9 Nethermost Pike 891 2923 Eastern 10 Catstycam 890 2920 Eastern 11 Esk Pike 885 2904 Southern 12 Raise 883 2897 Eastern 13 Fairfield 873 2864 Eastern 14 Blencathra 868 2848 Northern 15 Skiddaw Little Man 865 2838 Northern 16 White Side 863 2832 Eastern 17 Crinkle Crags 859 2818 Southern 18 Dollywagon Pike 858 2815 Eastern 19 Great Dodd 857 2812 Eastern 20 Stybarrow Dodd 843 2766 Eastern 21 Saint Sunday Crag 841 2759 Eastern 22 Scoat Fell 841 2759 Western 23 Grasmoor 852 2759 North Western 24 Eel Crag (Crag Hill) 839 2753 North Western 25 High Street 828 2717 Far Eastern 26 Red Pike (Wasdale) 826 2710 Western 27 Hart Crag 822 2697 Eastern 28 Steeple 819 2687 Western 29 High Stile 807 2648 Western 30 Coniston Old Man 803 2635 Southern 31 High Raise (Martindale) 802 2631 Far Eastern 32 Swirl How 802 2631 Southern 33 Kirk Fell 802 2631 Western 34 Green Gable 801 2628 Western 35 Lingmell 800 2625 Southern 36 Haycock 797 2615 Western 37 Brim Fell 796 2612 Southern 38 Dove Crag 792 2598 Eastern 39 Rampsgill Head 792 2598 Far Eastern 40 Grisedale Pike 791 2595 North Western 41 Watson's Dodd 789 2589 Eastern 42 Allen Crags 785 2575 Southern 43 Thornthwaite Crag 784 2572 Far Eastern 44 Glaramara 783 2569 Southern 45 Kidsty Pike 780 2559 Far -

Nutt No Name Nutt Ht Alt Area District Group Done Map Photo 1 Scafell

Nutt no Name Nutt ht Alt Area District Group Done Map Photo 1 Scafell Pike 3209 978 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Scafell Pike from Scafell 2 Scafell 3163 964 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Scafell 3 Symonds Knott 3146 959 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Symonds Knott 4 Helvellyn 3117 950 LAKE DISTRICT EAST HELVELLYN y map Helvellyn summit 5 Ill Crag 3068 935 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Ill Crag 6 Broad Crag 3064 934 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Broad Crag 7 Skiddaw 3054 931 LAKE DISTRICT NORTH SKIDDAW y map Skiddaw 8 Helvellyn Lower Man 3035 925 LAKE DISTRICT EAST HELVELLYN y map Helvellyn Lower Man from White Side 9 Great End 2986 910 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Great End 10 Bowfell 2959 902 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH BOWFELL y map Bowfell from Crinkle Crags 11 Great Gable 2949 899 LAKE DISTRICT WEST GABLE y map Great Gable from the Corridor Route 12 Cross Fell 2930 893 NORTH PENNINES WEST CROSS FELL y map Cross Fell summit 13 Pillar 2926 892 LAKE DISTRICT WEST PILLAR y map Pillar from Kirk Fell 14 Nethermost Pike 2923 891 LAKE DISTRICT EAST HELVELLYN y map Nethermost Pike summit 15 Catstycam 2920 890 LAKE DISTRICT EAST HELVELLYN y map Catstycam 16 Esk Pike 2904 885 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH BOWFELL y map Esk Pike 17 Raise 2897 883 LAKE DISTRICT EAST HELVELLYN y map Raise from White Side 18 Fairfield 2864 873 LAKE DISTRICT EAST FAIRFIELD y map Fairfield from Gavel Pike 19 Blencathra 2858 868 LAKE DISTRICT NORTH BLENCATHRA y map Blencathra 20 Bowfell North Top 2841 866 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH BOWFELL y map Bowfell North Top from -

Lake District Wainwright Bagging Holiday - the Far Eastern Fells

Lake District Wainwright Bagging Holiday - The Far Eastern Fells Tour Style: Challenge Walks Destinations: Lake District & England Trip code: DBWBF Trip Walking Grade: 6 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Wainwright bagging, perfect when you want to release your inner explorer! Alfred Wainwright’s Pictorial Guides have provided the inspiration for many a fell walker, with over two million copies of the books selling since their publication. There are 214 fells described within his books and this holiday takes in all 36 of the fells he enthuses about in his Far Eastern Fells pictorial guide, in one fabulous, challenging holiday. The Far Eastern Fells make up the beautiful and often remote section of fells from the eastern shores of Ullswater, around Haweswater and south to the Kentmere valley. In an energetic week of serious hiking it’s possible to do the lot. We criss-cross the mountains with a few out-and-back extensions here and there to make sure we bag every one. Some very tough days amongst some of Cumbria’s finest fells. HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Follow in the footsteps of Alfred Wainwright exploring some of his favourite fells • Bag all 36 of the summits in his Far Eastern Fells Pictorial Guide in one week • Enjoy challenging walking with wonderful views and a great sense of achievement www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 • Let an experienced walking leader bring classic routes often in remote offbeat areas to life • Enjoy magnificent Lake District scenery • Stay in a beautiful country house where you can relax and share stories of your day in the evenings TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded walking Activity Level 6. -

Kedal Fellwalkers Summer Programme 2003

Kendal Fellwalkers Programme Summer 2014 Information from: Secretary 01539 734766 or Programme Secretary 01524 762255 www.kendalfellwalkers.co.uk G Date r Area of Walk Leader Time at Starting Point Grid Time a Kendal Ref. walk d e starts 06/04/2014 A Black Crag, Holme Fell, John Jennings 08:30 Elterwater free CP 09:10 Wetherlam, Pike of Blisco, NY329051 Lingmoor (16mi 6000ft) B Green Crag, Harter Fell, Stony John Nash 08:30 Birker Moor (Devoke 09:30 Tarn (13mi 3800ft) Water junction) SD171977 C Greenburn Circuit (Helm Crag, Tony George 08:30 Layby on A591 north of 09:10 Calf Crag, Steel Fell) (8.5mi Swan Inn, Grasmere 2900ft) NY337086 13/04/2014 A Corpse Road, Branstree, Tarn Tim Lilley 08:30 Mardale Head CP 09:30 Crag, Grey Crag, Shipman Knotts, NY469107 Harter Fell (15mi 4800ft) B Wet Sleddale, Branstree, Swindale Steve Douglas 08:30 Wet Sleddale Dam 09:05 (13 mi 3000ft) NY555115 C Skiddaw, Sale How (10mi 3400ft) Derek Capper 08:30 Blencathra Centre 09:30 NY302257 20/04/2014 A White Maiden, Caw, White How, John Jennings 08:30 Fell Gate, Walna Scar CP 09:20 Green Crag, Harter Fell, Levers SD289970 Hause (16mi 5800ft) B Wether Hill, Loadpot Hill, Ken Taylor 08:30 Helton, grass verges W of 09:15 Bonscale Pike, Arthur's Pike village NY497214 (12.5mi 2200ft) C Burney Fell, Blawith Knott, John Wilkinson 08:30 Grizebeck, CP opposite 09:20 Woodland (11mi 1500ft) Greyhound Inn SD238850 27/04/2014 A Cam Crag, Glaramara, Scafell Jill Robertson 08:30 Stonethwaite NY262137 09:40 Pike, Corridor Route (14mi 4900ft) B Whernside and Great Coum (13mi -

Lake District Hewitts

Lake District Hewitts Climbed Date Name Metres Feet 1 Scafell Pike 978 m 3209 ft 2 Scafell 964 m 3163 ft 3 Helvellyn 950 m 3117 ft 4 Ill Crag 935 m 3068 ft 5 Broad Crag 934 m 3064 ft 6 Skiddaw 931 m 3054 ft 7 Great End 910 m 2986 ft 8 Bowfell 902 m 2959 ft 9 Great Gable 899 m 2949 ft 10 Pillar 892 m 2927 ft 11 Catstye Cam 890 m 2920 ft 12 Esk Pike 885 m 2904 ft 13 Raise 883 m 2897 ft 14 Fairfield 873 m 2864 ft 15 Blencathra 868 m 2848 ft 16 Skiddaw Little Man 865 m 2838 ft 17 White Side 863 m 2831 ft 18 Crinkle Crags 859 m 2818 ft 19 Dollywaggon Pike 858 m 2815 ft 20 Great Dodd 857 m 2812 ft 21 Grasmoor 852 m 2795 ft 22 Stybarrow Dodd 843 m 2766 ft 23 Scoat Fell 841 m 2759 ft 24 St Sunday Crag 841 m 2759 ft 25 Crag Hill 839 m 2753 ft 26 Crinkle Crags South Top 834 m 2736 ft 27 Black Crag 828 m 2717 ft 28 High Street 828 m 2717 ft 29 Red Pike (Wasdale) 826 m 2710 ft 30 Hart Crag 822 m 2697 ft 31 Shelter Crags 815 m 2674 ft 32 Lingmell 807 m 2648 ft 33 High Stile 807 m 2648 ft 34 Old Man of Coniston 803 m 2635 ft 35 Kirk Fell 802 m 2631 ft 36 High Raise 802 m 2631 ft 37 Swirl How 802 m 2631 ft 38 Green Gable 801 m 2628 ft 1 39 Haycock 797 m 2615 ft 40 Green Side 795 m 2608 ft 41 Dove Crag 792 m 2598 ft 42 Rampsgill Head 792 m 2598 ft 43 Grisedale Pike 791 m 2595 ft 44 Kirk Fell East Top 787 m 2582 ft 45 Allen Crags 785 m 2575 ft 46 Thornthwaite Crag 784 m 2572 ft 47 Glaramara 783 m 2569 ft 48 Harter Fell 778 m 2552 ft 49 Dow Crag 778 m 2552 ft 50 Red Screes 776 m 2546 ft 51 Sail 773 m 2536