MTO 10.2: Gloag, Review of the Music and Thought of Michael Tippett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Party Pieces to Find a Pathway Through It So That I Have Some Feeling for the Shape and the Climaxes

For most people, reaching the age of 60 is a signal to take two of the pieces had arrived - Henze’s intriguingly-titled things easy, to enjoy the benefits of free travel or take that Scorribanda pianistica, and Olicantus, a slow ragtime from world cruise you’d always promised yourself. But pianist George Benjamin, a composer whose music Crossley has Paul Crossley will spend his 60th birthday on 17 May long championed. All five commissions have their origins giving a recital in the Wigmore Hall. The first half of the in their composers’ orchestral output. Scorribanda recital comprises premieres of five new works pianistica, roughly translated as ‘pianistic raiding-party”, commissioned by Crossley and in the second half he plays plunders an earlier orchestral work by Henze which itself one of his party-pieces - Debussy’s Preludes Book 2. It is a raided material from an even earlier work. The title of very Salonen’s piece is Scheggia, literally ‘fragment or ‘chip’ (as in ‘chip off the old block). How does Crossley tackle a new piece once it has dropped on to the doormat? ‘I do what I always do. I hack my way through the jungle from beginning to end. I have Party pieces to find a pathway through it so that I have some feeling for the shape and the climaxes. Then I get down to details.’ Pianist Paul Crossley special birthday present to himself from a pianist Crossley considers himself very fortunate that his whose profile is perhaps not so high as it once was. playing career happened at the right time and concedes has commissioned five There have been three constants in Crossley’s pub- that it’s far harder for a young performer these days to lic pianistic life: the French repertoire and the music carve a niche. -

Tippett Stereo Add Set

SRCD.2217 2 CD TIPPETT STEREO ADD SET SIR MICHAEL TIPPETT (1905 - 1998) THE MIDSUMMER MARRIAGE Opera in Three Acts CD1 1 - 15 Act I 61’50” CD 2 1 - 5 Act II (completion) 19’13” 16 - 19 Act II (start) 14’15” (76’07”) 6 - 21 Act III 58’13” (77’27”) (153’34”) Mark, a young man of unknown parentage (tenor) . Alberto Remedios Jenifer, his betrothed, a young girl (soprano) . Joan Carlyle King Fisher, Jenifer's father, a businessman (baritone) . Raimund Herincx Bella, King Fisher's secretary (soprano) . Elizabeth Harwood Jack, Bella's boyfriend, a mechanic (tenor) . .. Stuart Burrows Sosostris, a clairvoyante (contralto) . Helen Watts The Ancients: Priest (He-Ancient) (bass) . Stafford Dean The Ancients: Priestess (She-Ancient) (mezzo) . Elizabeth Bainbridge Half-Tipsy Man (baritone): David Whelan. A Dancing Man (tenor): Andrew Daniels Mark's and Jenifer's friends: Chorus. Strephon, dancer attendant on the Ancients (silent) Chorus & Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden (Chorus Master: Douglas Robinson, Conductor's Assistant: David Shaw) Chorus & Orchestra of the The above individual timings will normally include two pauses, one before the beginning and one after the end of each Act. Royal Opera House, Covent Garden P 1971 The copyright in this sound recording is owned by Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Digital remastering P 1995 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Sir Colin Davis ©1995 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Lyrita is a registered trade mark. Made in the U.K. Alberto Remedios • Joan Carlyle • Raimund Herincx • Elizabeth Harwood LYRITA RECORDED EDITION. Produced under an exclusive license from Lyrita by Wyastone Estate Limited, PO Box 87, Monmouth, NP25 3WX, UK 48 Stuart Burrows • Helen Watts • Stafford1 Dean • Elizabeth Bainbridge CD 1 (76’07”) Act I (61’50”) Act II (start) (14’15”) Make haste, ALL “All things fall and are built again 1 Scene 1 This way! This way! 3’45” Make haste And those that build them again are gay!” To find the way 2 What’s that? Surely music? 1’07” In the dark 3 Scene 2 (leading to:) 0’51” To another day. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2017). Michael Finnissy - The Piano Music (10 and 11) - Brochure from Conference 'Bright Futures, Dark Pasts'. This is the other version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17523/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] BRIGHT FUTURES, DARK PASTS Michael Finnissy at 70 Conference at City, University of London January 19th-20th 2017 Bright Futures, Dark Pasts Michael Finnissy at 70 After over twenty-five years sustained engagement with the music of Michael Finnissy, it is my great pleasure finally to be able to convene a conference on his work. This event should help to stimulate active dialogue between composers, performers and musicologists with an interest in Finnissy’s work, all from distinct perspectives. It is almost twenty years since the publication of Uncommon Ground: The Music of Michael Finnissy (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998). -

Children in Opera

Children in Opera Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Sutherland Front cover: ©Scott Armstrong, Perth, Western Australia All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6166-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6166-3 In memory of Adrian Maydwell (1993-2019), the first Itys. CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xxi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction What is a child? ..................................................................................... 4 Vocal development in children ............................................................. 5 Opera sacra ........................................................................................... 6 Boys will be girls ................................................................................. -

Clarkes Direkter, Leidenschaftlicher Musik Welker Uraufgeführt

570429bk EU 14/9/07 3:46 pm Page 8 gestört. Black Fire wurde in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, unter Es ist nicht nötig, etwas von diesen Dingen zu wis- der Leitung des inzwischen verstorbenen Gerald Loren sen, um sich an Clarkes direkter, leidenschaftlicher Musik Welker uraufgeführt. erfreuen zu können; er aber hält es nicht für nötig, seine Einige Zeit nach der Premiere stellte Clarke fest, dass Anregungen zu verbergen und spricht immer freimütig er, ohne es zu wissen, schon ein Vorspiel zu diesem Stück von den „Auslösern“, die ihn faszinieren und inspirieren. geschrieben hatte – in Gestalt seines frühen Trompeten- werkes Premonitions. Dieses wurde zu einer passenden, Nigel an Ives erinnernden Frage und geht als Auftakt dem Klang Stella Wilson und der Wut von Black Fire voran. Deutsche Fassung: Cris Posslac CLARKE Samurai • Black Fire The Miraculous Violin Peter Sheppard Skærved, Violin Ivan Hutchinson, Trumpet Band of HM Royal Marines, Plymouth Longbow Band of HM Royal Marines, Plymouth, conducted by Lt Col Chris Davis, recording Black Fire with Lt Col Chris Davis Peter Sheppard Skærved at HMS Raleigh, Plymouth. 8.570429 8 570429bk EU 14/9/07 3:46 pm Page 2 Nigel Clarke (b.1960) Dieser informatorische Ansatz bildet auch die 1995 erhielt Nigel Clarke den Auftrag zu Samurai für Pernambuco · The Miraculous Violin · Loulan · Samurai · Premonitions · Black Fire Grundlage von Pernambuco, dem ältesten Violinstück Timothy Reynish und das symphonische Blasorchester auf dieser CD. Clarke nahm sich vor, ein Werk über den des Royal Northern College of Music im nordenglischen Nigel Clarke began his musical career as a military Andelko Krpan leant over to Sheppard Skærved. -

The Perfect Fool (1923)

The Perfect Fool (1923) Opera and Dramatic Oratorio on Lyrita An OPERA in ONE ACT For details visit https://www.wyastone.co.uk/all-labels/lyrita.html Libretto by the composer William Alwyn. Miss Julie SRCD 2218 Cast in order of appearance Granville Bantock. Omar Khayyám REAM 2128 The Wizard Richard Golding (bass) Lennox Berkeley. Nelson The Mother Pamela Bowden (contralto) SRCD 2392 Her son, The Fool speaking part Walter Plinge Geoffrey Bush. Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime REAM 1131 Three girls: Alison Hargan (soprano) Gordon Crosse. Purgatory SRCD 313 Barbara Platt (soprano) Lesley Rooke (soprano) Eugene Goossens. The Apocalypse SRCD 371 The Princess Margaret Neville (soprano) Michael Hurd. The Aspern Papers & The Night of the Wedding The Troubadour John Mitchinson (tenor) The Traveller David Read (bass) SRCD 2350 A Peasant speaking part Ronald Harvi Walter Leigh. Jolly Roger or The Admiral’s Daughter REAM 2116 Narrator George Hagan Elizabeth Maconchy. Héloïse and Abelard REAM 1138 BBC Northern Singers (chorus-master, Stephen Wilkinson) Thea Musgrave. Mary, Queen of Scots SRCD 2369 BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra (Leader, Reginald Stead) Conducted by Charles Groves Phyllis Tate. The Lodger REAM 2119 Produced by Lionel Salter Michael Tippett. The Midsummer Marriage SRCD 2217 A BBC studio recording, broadcast on 7 May 1967 Ralph Vaughan Williams. Sir John in Love REAM 2122 Cover image : English: Salamander- Bestiary, Royal MS 1200-1210 REAM 1143 2 REAM 1143 11 drowned in a surge of trombones. (Only an ex-addict of Wagner's operas could have 1 The WIZARD is performing a magic rite 0.21 written quite such a devastating parody as this.) The orchestration is brilliant throughout, 2 WIZARD ‘Spirit of the Earth’ 4.08 and in this performance Charles Groves manages to convey my father's sense of humour Dance of the Spirits of the Earth with complete understanding and infectious enjoyment.” 3 WIZARD. -

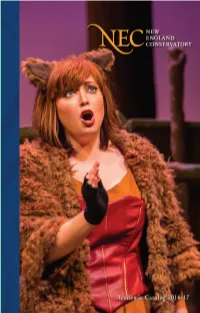

Academiccatalog 2017.Pdf

New England Conservatory Founded 1867 290 Huntington Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 necmusic.edu (617) 585-1100 Office of Admissions (617) 585-1101 Office of the President (617) 585-1200 Office of the Provost (617) 585-1305 Office of Student Services (617) 585-1310 Office of Financial Aid (617) 585-1110 Business Office (617) 585-1220 Fax (617) 262-0500 New England Conservatory is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges. New England Conservatory does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, age, national or ethnic origin, sexual orientation, physical or mental disability, genetic make-up, or veteran status in the administration of its educational policies, admission policies, employment policies, scholarship and loan programs or other Conservatory-sponsored activities. For more information, see the Policy Sections found in the NEC Student Handbook and Employee Handbook. Edited by Suzanne Hegland, June 2016. #e information herein is subject to change and amendment without notice. Table of Contents 2-3 College Administrative Personnel 4-9 College Faculty 10-11 Academic Calendar 13-57 Academic Regulations and Information 59-61 Health Services and Residence Hall Information 63-69 Financial Information 71-85 Undergraduate Programs of Study Bachelor of Music Undergraduate Diploma Undergraduate Minors (Bachelor of Music) 87 Music-in-Education Concentration 89-105 Graduate Programs of Study Master of Music Vocal Pedagogy Concentration Graduate Diploma Professional String Quartet Training Program Professional -

The Critical Reception of Tippett's Operas

Between Englishness and Modernism: The Critical Reception of Tippett’s Operas Ivan Hewett (Royal College of Music) [email protected] The relationship between that particular form of national identity and consciousness we term ‘Englishness’ and modernism has been much discussed1. It is my contention in this essay that the critical reception of the operas of Michael Tippett sheds an interesting and revealing light on the relationship at a moment when it was particularly fraught, in the decades following the Second World War. Before approaching that topic, one has to deal first with the thorny and many-sided question as to how and to what extent those operas really do manifest a quality of Englishness. This is more than a parochial question of whether Tippett is a composer whose special significance for listeners and opera-goers in the UK is rooted in qualities that only we on these islands can perceive. It would hardly be judged a triumph for Tippett if that question were answered in the affirmative. On the contrary, it would be perceived as a limiting factor — perhaps the very factor that prevents Tippett from exporting overseas as successfully as his great rival and antipode, Benjamin Britten. But even without that hard evidence of Tippett’s limited appeal, the very idea that his Englishness forms a major part of his significance could in itself be a disabling feature of the music. We are squeamish these days about granting a substantive aesthetic value to music on the grounds of its national qualities, if the composer in question is not safely locked away in the relatively remote past. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Archives

rille01111 .2 /rm. .T111/1 WEIW 1/1=.'/ 111 L VI. MO.7f./ 4/1101 -.111 1-/II• MB .4/ %/1/1111i11/ 11•14= ■• MIN 11111114•11111111111M SWOON 111111114/6/11=111111 NM • . • , i , Inm• pig• =No nim• • ■11111 1•111•1111111111 Mel 44•11/114!•1•1•11111111111=1•1•11141=0•11•MITIP . MN." 1111/11111111.: r- um en= 2. VI. II /"...111•1141■41T•/ I •111/. 11/11.1eVr =MIN Ur .1109111111111/.. MIK PM of Ji.7.1.41111 1:,,-, • .• •P11.411/1111•111414 AJMER MI111111011111•1414. IIIMM MI IP 111/Mill•IMIN - ■///MALMIll■ .....011111111 irs. _ • m••••••••••• ono m••-■•••• ► • r • Art IIIIIhwew -4••••••.... it."2"="110•1=9.ir Via 0111.:J/W ON1111•11114MINM I .11•111•111/1111111/ MOW= Wig 1•1•161111111111.1111 ININIUMMI 1111.11rnall ona cr IN 1111111•10/MININ WIMP •// MEMINIMIN IN ■MIIIMME■ Mari 4114 lye CA V.I. '''......"..11.010. II. 1 P - 1•11M•P" MEW' • • ••• •1 NUN= M •, /NNW ....g.=.....= •!•••••■•■•••18...•• • • • II •••••IN•1•1■11 Vic. 7' Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor Friday, January 2, 1976 at 2:00 p.m. Saturday, January 3, 1976 at 8:30 p.m. Tuesday, January 6, 1976 at 8:30 p.m. Symphony Hall, Boston Ninety-fifth Season Baldwin Piano Deutsche Grammophon Records Program Program Notes Michael Tilson Thomas conducting Gustav Mahler (1860 - 1911) Sketches for the Ninth Symphony were made in 1909 Mahler: Symphony No. 9 in D and the work was completed on April 1, 1910. -

The Operas of Michael Tippett : the Inner Values of Tippett As Portrayed

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. The Operas of Michael Tippett: The Inner Values of Tippett as Portrayed by Selected Female Characters A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of. Philosophy Ill Music at Massey University, New Zealand Julie Jackson-Tretchikoff 2006 for my cfear li:us6ancf (l)imitri wno nas wnofe-neartec[(y encouragecf me to pursue a [ifefong cfream Abstract Sir Michael Kemp Tippett (1905-1998) was a British composer who wrote five operas. This dissertation explores the dramatic and musical presentation of five selected female characters, one from each of Tippett's operas: Sosostris (alto) The Midsummer Marriage (1955); Helen (mezzo-soprano) King Priam (1962); Denise ( dramatic soprano) The Knot Garden (1970); Hannah (rich mezzo) The Ice Break (1977); Jo Ann (lyric soprano) New Year (1989). It is argued that each of the five selected characters portrays Tippett' s inner values of humanitarianism, compassion, integrity and optimism. The dissertation focuses on certain key moments in each opera with an analysis of a central aria. Due to the writer's interest in the performance aspect of these operas, discussion centres on melody, the timbre of voice-types linked with instrumentation, rhythm, word setting and the vexed question of Tippett's libretti. 11 Acknowledgements I would particularly like to acknowledge the assistance and encouragement given to me by my UK supervisor, Dr Claire Seymour. -

Nonatonic Harmonic Structures in Symphonies by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax Cameron Logan [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 12-2-2014 Nonatonic Harmonic Structures in Symphonies by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax Cameron Logan [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Logan, Cameron, "Nonatonic Harmonic Structures in Symphonies by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 603. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/603 i Nonatonic Harmonic Structures in Symphonies by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax Cameron Logan, Ph.D. University of Connecticut, 2014 This study explores the pitch structures of passages within certain works by Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax. A methodology that employs the nonatonic collection (set class 9-12) facilitates new insights into the harmonic language of symphonies by these two composers. The nonatonic collection has received only limited attention in studies of neo-Riemannian operations and transformational theory. This study seeks to go further in exploring the nonatonic‟s potential in forming transformational networks, especially those involving familiar types of seventh chords. An analysis of the entirety of Vaughan Williams‟s Fourth Symphony serves as the exemplar for these theories, and reveals that the nonatonic collection acts as a connecting thread between seemingly disparate pitch elements throughout the work. Nonatonicism is also revealed to be a significant structuring element in passages from Vaughan Williams‟s Sixth Symphony and his Sinfonia Antartica. A review of the historical context of the symphony in Great Britain shows that the need to craft a work of intellectual depth, simultaneously original and traditional, weighed heavily on the minds of British symphonists in the early twentieth century. -

The Late Choral Works of Igor Stravinsky

THE LATE CHORAL WORKS OF IGOR STRAVINSKY: A RECEPTION HISTORY _________________________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia ________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ____________________________ by RUSTY DALE ELDER Dr. Michael Budds, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2008 The undersigned, as appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled THE LATE CHORAL WORKS OF IGOR STRAVINSKY: A RECEPTION HISTORY presented by Rusty Dale Elder, a candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _________________________________________ Professor Michael Budds ________________________________________ Professor Judith Mabary _______________________________________ Professor Timothy Langen ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to each member of the faculty who participated in the creation of this thesis. First and foremost, I wish to recognize the ex- traordinary contribution of Dr. Michael Budds: without his expertise, patience, and en- couragement this study would not have been possible. Also critical to this thesis was Dr. Judith Mabary, whose insightful questions and keen editorial skills greatly improved my text. I also wish to thank Professor Timothy Langen for his thoughtful observations and support. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………...ii ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………...v CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION: THE PROBLEM OF STRAVINSKY’S LATE WORKS…....1 Methodology The Nature of Relevant Literature 2. “A BAD BOY ALL THE WAY”: STRAVINSKY’S SECOND COMPOSITIONAL CRISIS……………………………………………………....31 3. AFTER THE BOMB: IN MEMORIAM DYLAN THOMAS………………………45 4. “MURDER IN THE CATHEDRAL”: CANTICUM SACRUM AD HONOREM SANCTI MARCI NOMINIS………………………………………………………...60 5.