From Catchment to Inner Shelf: Insights Into Nsw Coastal Compartments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To View More Samplers Click Here

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au · The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources books on fully searchable CD-ROM · 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide · A complete range of Genealogy software · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Specialist Directories, War records, Regional Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter histories etc. FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources www.familyphotobook.com.au · free information and content, www.worldvitalrecords.com.au newsletters and blogs, speaker · Free software download to create biographies, topic details · 50 million Australasian records professional looking personal photo books, · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, · 1 billion records world wide calendars and more organisations and commercial partners · low subscriptions · FREE content daily and some permanently New South Wales Almanac and Country Directory 1924 Ref. AU2115-1924 ISBN: 978 1 74222 770 2 This book was kindly loaned to Archive Digital Books Australasia by the University of Queensland Library www.library.uq.edu.au Navigating this CD To view the contents of this CD use the bookmarks and Adobe Reader’s forward and back buttons to browse through the pages. -

Cape York Peninsula Parks and Reserves Visitor Guide

Parks and reserves Visitor guide Featuring Annan River (Yuku Baja-Muliku) National Park and Resources Reserve Black Mountain National Park Cape Melville National Park Endeavour River National Park Kutini-Payamu (Iron Range) National Park (CYPAL) Heathlands Resources Reserve Jardine River National Park Keatings Lagoon Conservation Park Mount Cook National Park Oyala Thumotang National Park (CYPAL) Rinyirru (Lakefield) National Park (CYPAL) Great state. Great opportunity. Cape York Peninsula parks and reserves Thursday Possession Island National Park Island Pajinka Bamaga Jardine River Resources Reserve Denham Group National Park Jardine River Eliot Creek Jardine River National Park Eliot Falls Heathlands Resources Reserve Captain Billy Landing Raine Island National Park (Scientific) Saunders Islands Legend National Park National park Sir Charles Hardy Group National Park Mapoon Resources reserve Piper Islands National Park (CYPAL) Wen Olive River loc Conservation park k River Wuthara Island National Park (CYPAL) Kutini-Payamu Mitirinchi Island National Park (CYPAL) Water Moreton (Iron Range) Telegraph Station National Park Chilli Beach Waterway Mission River Weipa (CYPAL) Ma’alpiku Island National Park (CYPAL) Napranum Sealed road Lockhart Lockhart River Unsealed road Scale 0 50 100 km Aurukun Archer River Oyala Thumotang Sandbanks National Park Roadhouse National Park (CYPAL) A r ch KULLA (McIlwraith Range) National Park (CYPAL) er River C o e KULLA (McIlwraith Range) Resources Reserve n River Claremont Isles National Park Coen Marpa -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

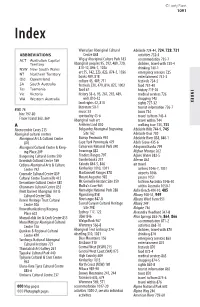

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Water Research Laboratory

Water Research Laboratory Never Stand Still Faculty of Engineering School of Civil and Environmental Engineering Eurobodalla Coastal Hazard Assessment WRL Technical Report 2017/09 October 2017 by I R Coghlan, J T Carley, A J Harrison, D Howe, A D Short, J E Ruprecht, F Flocard and P F Rahman Project Details Report Title Eurobodalla Coastal Hazard Assessment Report Author(s) I R Coghlan, J T Carley, A J Harrison, D Howe, A D Short, J E Ruprecht, F Flocard and P F Rahman Report No. 2017/09 Report Status Final Date of Issue 16 October 2017 WRL Project No. 2014105.01 Project Manager Ian Coghlan Client Name 1 Umwelt Australia Pty Ltd Client Address 1 75 York Street PO Box 3024 Teralba NSW 2284 Client Contact 1 Pam Dean-Jones Client Name 2 Eurobodalla Shire Council Client Address 2 89 Vulcan Street PO Box 99 Moruya NSW 2537 Client Contact 2 Norman Lenehan Client Reference ESC Tender IDs 216510 and 557764 Document Status Version Reviewed By Approved By Date Issued Draft J T Carley G P Smith 9 June 2017 Final Draft J T Carley G P Smith 1 September 2017 Final J T Carley G P Smith 16 October 2017 This report was produced by the Water Research Laboratory, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of New South Wales for use by the client in accordance with the terms of the contract. Information published in this report is available for release only with the permission of the Director, Water Research Laboratory and the client. It is the responsibility of the reader to verify the currency of the version number of this report. -

FF Directory

Directory WFF (World Flora Fauna Program) - Updated 30 November 2012 Directory WorldWide Flora & Fauna - Updated 30 November 2012 Release 2012.06 - by IK1GPG Massimo Balsamo & I5FLN Luciano Fusari Reference Name DXCC Continent Country FF Category 1SFF-001 Spratly 1S AS Spratly Archipelago 3AFF-001 Réserve du Larvotto 3A EU Monaco 3AFF-002 Tombant à corail des Spélugues 3A EU Monaco 3BFF-001 Black River Gorges 3B8 AF Mauritius I. 3BFF-002 Agalega is. 3B6 AF Agalega Is. & St.Brandon I. 3BFF-003 Saint Brandon Isls. (aka Cargados Carajos Isls.) 3B7 AF Agalega Is. & St.Brandon I. 3BFF-004 Rodrigues is. 3B9 AF Rodriguez I. 3CFF-001 Monte-Rayses 3C AF Equatorial Guinea 3CFF-002 Pico-Santa-Isabel 3C AF Equatorial Guinea 3D2FF-001 Conway Reef 3D2 OC Conway Reef 3D2FF-002 Rotuma I. 3D2 OC Conway Reef 3DAFF-001 Mlilvane 3DA0 AF Swaziland 3DAFF-002 Mlavula 3DA0 AF Swaziland 3DAFF-003 Malolotja 3DA0 AF Swaziland 3VFF-001 Bou-Hedma 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-002 Boukornine 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-003 Chambi 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-004 El-Feidja 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-005 Ichkeul 3V AF Tunisia National Park, UNESCO-World Heritage 3VFF-006 Zembraand Zembretta 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-007 Kouriates Nature Reserve 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-008 Iles de Djerba 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-009 Sidi Toui 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-010 Tabarka 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-011 Ain Chrichira 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-012 Aina Zana 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-013 des Iles Kneiss 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-014 Serj 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-015 Djebel Bouramli 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-016 Djebel Khroufa 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-017 Djebel Touati 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-018 Etella Natural 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-019 Grotte de Chauve souris d'El Haouaria 3V AF Tunisia National Park, UNESCO-World Heritage 3VFF-020 Ile Chikly 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-021 Kechem el Kelb 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-022 Lac de Tunis 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-023 Majen Djebel Chitane 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-024 Sebkhat Kelbia 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-025 Tourbière de Dar. -

South Eastern

! ! ! Mount Davies SCA Abercrombie KCR Warragamba-SilverdaleKemps Creek NR Gulguer NR !! South Eastern NSW - Koala Records ! # Burragorang SCA Lea#coc#k #R###P Cobbitty # #### # ! Blue Mountains NP ! ##G#e#org#e#s# #R##iver NP Bendick Murrell NP ### #### Razorback NR Abercrombie River SCA ! ###### ### #### Koorawatha NR Kanangra-Boyd NP Oakdale ! ! ############ # # # Keverstone NPNuggetty SCA William Howe #R####P########## ##### # ! ! ############ ## ## Abercrombie River NP The Oaks ########### # # ### ## Nattai SCA ! ####### # ### ## # Illunie NR ########### # #R#oyal #N#P Dananbilla NR Yerranderie SCA ############### #! Picton ############Hea#thco#t#e NP Gillindich NR Thirlmere #### # ! ! ## Ga!r#awa#rra SCA Bubalahla NR ! #### # Thirlmere Lak!es NP D!#h#a#rawal# SCA # Helensburgh Wiarborough NR ! ##Wilto#n# # ###!#! Young Nattai NP Buxton # !### # # ##! ! Gungewalla NR ! ## # # # Dh#arawal NR Boorowa Thalaba SCA Wombeyan KCR B#a#rgo ## ! Bargo SCA !## ## # Young NR Mares Forest NPWollondilly River NR #!##### I#llawarra Esc#arpment SCA # ## ## # Joadja NR Bargo! Rive##r SC##A##### Y!## ## # ! A ##Y#err#i#nb#ool # !W # #### # GH #C##olo Vale## # Crookwell H I # ### #### Wollongong ! E ###!## ## # # # # Bangadilly NP UM ###! Upper# Ne##pe#an SCA ! H Bow##ral # ## ###### ! # #### Murrumburrah(Harden) Berri#!ma ## ##### ! Back Arm NRTarlo River NPKerrawary NR ## ## Avondale Cecil Ho#skin#s# NR# ! Five Islands NR ILLA ##### !# W ######A#Y AR RA HIGH##W### # Moss# Vale Macquarie Pass NP # ! ! # ! Macquarie Pass SCA Narrangarril NR Bundanoon -

Redistribution of New South Wales Into Electoral Divisions FEBRUARY 2016

Redistribution of New South Wales into electoral divisions FEBRUARY 2016 Report of the augmented Electoral Commission for New South Wales Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 Feedback and enquiries Feedback on this report is welcome and should be directed to the contact officer. Contact officer National Redistributions Manager Roll Management Branch Australian Electoral Commission 50 Marcus Clarke Street Canberra ACT 2600 Locked Bag 4007 Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone: 02 6271 4411 Fax: 02 6215 9999 Email: [email protected] AEC website www.aec.gov.au Accessible services Visit the AEC website for telephone interpreter services in 18 languages. Readers who are deaf or have a hearing or speech impairment can contact the AEC through the National Relay Service (NRS): – TTY users phone 133 677 and ask for 13 23 26 – Speak and Listen users phone 1300 555 727 and ask for 13 23 26 – Internet relay users connect to the NRS and ask for 13 23 26 ISBN: 978-1-921427-44-2 © Commonwealth of Australia 2016 © State of New South Wales 2016 The report should be cited as augmented Electoral Commission for New South Wales, Redistribution of New South Wales into electoral divisions. 15_0526 The augmented Electoral Commission for New South Wales (the augmented Electoral Commission) has undertaken a redistribution of New South Wales. In developing and considering the impacts of the redistribution, the augmented Electoral Commission has satisfied itself that the electoral divisions comply with the requirements of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (the Electoral Act). The augmented Electoral Commission commends its redistribution for New South Wales. This report is prepared to fulfil the requirements of section 74 of the Electoral Act. -

The Ultimate South Coast Oyster Trail

RESTAURANT AUSTRALIA | MEDIA INFORMATION THE ULTIMATE SOUTH COAST OYSTER TRAIL When it comes to unspoilt destinations, the NSW South Coast is postcard perfect. This meandering drive south from Sydney unearths an astonishing range of local wines, cheeses, vegetables and seafood – plus oysters as the star ingredient! Local hero: oysters The pristine lakes, rivers and ocean found here form a large chunk of Australia’s 300 km-long Oyster Coast – with farms sprinkled across the Shoalhaven and Crookhaven rivers, Clyde River, Wagonga Inlet and the lakes at Tuross, Wapengo, Merimbula, Pambula and Wonboyn. Local oyster farmers are committed to ensuring that these estuaries are among the most environmentally sustainable oyster-growing regions in the world. The local specialty is the Sydney rock oyster, one of the few indigenous oysters still being farmed anywhere in the world and prized for its intense and tangy flavour. DAY 1: SYDNEY TO MOLLYMOOK Morning Starting from Sydney, travel south along the coast past beautiful beaches around Wollongong, Shellharbour and Kiama to the Shoalhaven Coast wine region. The breathtaking beauty of the countryside, the beaches and towering escarpment ensure that the vineyards here are among the most beautiful in Australia. Each of the 18 vineyards in the region has cellar doors where you can try a wide variety of red and white styles. Visit Gerringong’s Crooked River Wines which takes in a landscape that literally stretches from the mountains to the sea; Two Figs Winery that sits proudly overlooking the Shoalhaven River and offers a simply breathtaking view; and Coolangatta Estate near Berry to taste their award-winning semillon. -

FAR SOUTH COAST BIRDWATCHERS Inc. Affiliated with Birdlife Australia

PO Box 180 Pambula NSW 2549 Volume 21 Number 6 FAR SOUTH COAST BIRDWATCHERS Inc. Affiliated with BirdLife Australia NEWSLETTER NOV/DEC 2016 MERRY CHRISTMAS An early Christmas present for birdwatchers in our region has been the influx of Scarlet Honeyeaters. Good numbers of immature birds were observed along with the adults. This beautiful image of a Scarlet Honeyeater on a Callistemon was captured by Max Sutcliffe. Who needs holly and ivy when you can have Christmas colours like this? . ROBERT EDWARD HIGH 1939 – 2016 EVENING MEETING Thursday Dec 8, 2016 On October 12, 2016 our friend Rob High died peacefully at his home, aged 77, after a lengthy battle with a progressive illness. Meet in the Uniting Church Hall, Henwood St, Rob was a long-time supporter of Far South Coast Birdwatchers, always Merimbula, for a 7:30 pm personally welcoming birdwatchers to his property Mandeni, a prime birding start. location which he developed over many years. This is also the club’s AGM, to be followed by a Known for his astute, enquiring mind and his humanitarian philanthropy, he showing of photos and contributed to the community quietly in many ways. He will be greatly missed and talks by members. long remembered. We extend deepest sympathy to Rob’s family. IN THIS ISSUE Rob was instrumental in drawing attention to the destruction of his eucalypts at Meeting Report (Oct) 2 Mandeni, and blaming the Bell Miners, obtained a licence to undertake a Scientific President’s Message 2 Trial and eliminate over 2000 birds. This was not an easily granted approval and an New Members 3 expensive process for him. -

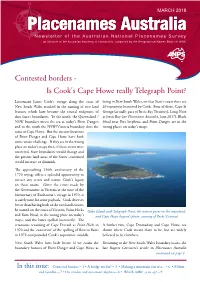

Contested Borders - Is Cook's Cape Howe Really Telegraph Point?

MARCH 2018 Newsletter of the Australian National Placenames Survey an initiative of the Australian Academy of Humanities, supported by the Geographical Names Board of NSW Contested borders - Is Cook's Cape Howe really Telegraph Point? Lieutenant James Cook's voyage along the coast of being in New South Wales, on that State's coast there are New South Wales resulted in the naming of two land 26 toponyms bestowed by Cook. Four of these, Cape St features which later became the coastal endpoints of George (actually part of Jervis Bay Territory), Long Nose that State’s boundaries. To the north, the Queensland / at Jervis Bay (see Placenames Australia, June 2017), Black NSW boundary meets the sea at today's Point Danger, Head near Port Stephens, and Point Danger, are in the and to the south the NSW/Victoria boundary does the wrong places on today's maps. same at Cape Howe. But the current locations of Point Danger and Cape Howe have both come under challenge. If they are in the wrong place on today's maps then, if these errors were corrected, State boundaries would change and the present land areas of the States concerned would increase or diminish. The approaching 250th anniversary of the 1770 voyage offers a splendid opportunity to correct any errors and restore Cook's legacy on these coasts. Given the errors made by the Government in Victoria at the time of the bicentenary of Endeavour's voyage in 1970, it is surely time for some payback. Cook deserves better than having both of the two land features he named on the coast of Victoria, Point Hicks Gabo Island with Telegraph Point, the nearest point on the mainland, and Ram Head, in the wrong place on today's and Cape Howe beyond (photo: courtesy of Parks Victoria) maps, and the latter spelled incorrectly. -

NPWS Annual Report 2000-2001 (PDF

Annual report 2000-2001 NPWS mission NSW national Parks & Wildlife service 2 Contents Director-General’s foreword 6 3 Conservation management 43 Working with Aboriginal communities 44 Overview 8 Joint management of national parks 44 Mission statement 8 Performance and future directions 45 Role and functions 8 Outside the reserve system 46 Partners and stakeholders 8 Voluntary conservation agreements 46 Legal basis 8 Biodiversity conservation programs 46 Organisational structure 8 Wildlife management 47 Lands managed for conservation 8 Performance and future directions 48 Organisational chart 10 Ecologically sustainable management Key result areas 12 of NPWS operations 48 Threatened species conservation 48 1 Conservation assessment 13 Southern Regional Forest Agreement 49 NSW Biodiversity Strategy 14 Caring for the environment 49 Regional assessments 14 Waste management 49 Wilderness assessment 16 Performance and future directions 50 Assessment of vacant Crown land in north-east New South Wales 19 Managing our built assets 51 Vegetation surveys and mapping 19 Buildings 51 Wetland and river system survey and research 21 Roads and other access 51 Native fauna surveys and research 22 Other park infrastructure 52 Threat management research 26 Thredbo Coronial Inquiry 53 Cultural heritage research 28 Performance and future directions 54 Conservation research and assessment tools 29 Managing site use in protected areas 54 Performance and future directions 30 Performance and future directions 54 Contributing to communities 55 2 Conservation planning -

From Catchment to Inner Shelf: Insights Into NSW Coastal Compartments

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health 1-1-2015 From catchment to inner shelf: insights into NSW coastal compartments Rafael Cabral Carvalho University of Wollongong, [email protected] Colin D. Woodroffe University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cabral Carvalho, Rafael and Woodroffe, Colin D., "From catchment to inner shelf: insights into NSW coastal compartments" (2015). Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers: part A. 4632. https://ro.uow.edu.au/smhpapers/4632 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] From catchment to inner shelf: insights into NSW coastal compartments Abstract This paper addresses the coastal compartments of the eastern coast by analysing characteristics of the seven biggest catchments in NSW (Shoalhaven, Hawkesbury, Hunter, Manning, Macleay, Clarence and Richmond) and coastal landforms such as estuaries, sand barriers, beaches, headlands, nearshore and inner shelf, providing a framework for estimating sediment budgets by delineating compartment boundaries and defining management units. It sheds light on the sediment dispersal yb rivers and longshore drift by reviewing literature, using available information/data, and modelling waves and sediment dispersal. Compartments were delineated based on physical characteristics through interpretation of hydrologic, geomorphic, geophysical, sedimentological, oceanographic factors and remote sensing. Results include identification of 36 primary compartments along the NSW coast, 80 secondary compartments on the South and Central coast, and 5 tertiary compartments for the Shoalhaven sector.