Nepali English’: a New Version of English?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Does Washback Exist?

DOCUMENT RESUME FL 020 178 ED 345 513 AUTHOR Alderson, J. Charles; Wall,Dianne TITLE Does Washback Exist? PUB DATE Feb 92 Symposium on the NOTE 23p.; Paper presented at a Educational and Social Impactsof Language Tests, Language Testing ResearchColloquium (February 1992). For a related document, seeFL 020 177. PUB TYPE Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility(142) Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Classroom Techniques;Educational Environment; Educational Research; EducationalTheories; Foreign Countries; Language Research;*Language Tests; *Learning Processes; LiteratureReviewa; Research Needs; Second LanguageInstruction; *Second Languages; *Testing the Test; Turkey IDENTIFIERS Nepal; Netherlands; *Teaching to ABSTRACT The concept of washback, orbackwash, defined as the influence of testing oninstruction, is discussed withrelation to second second language teaching andtesting. While the literature of be language testing suggests thattests are commonly considered to powerful determiners of whathappens in the classroom, Lheconcept of washback is not well defined.The first part of the discussion focuses on the concept, includingseveral different interpretations of the phenomenon. It isfound to be a far more complextopic than suggested by the basic washbackhypothesis, which is alsodiscussed and outlined. The literature oneducation in general is thenreviewed for additional information on theissues involved. Very little several research was found that directlyrelated to the subject, but studies are highlighted.Following this, empirical research on language testing is consulted forfurther insight. Studies in Turkey, the Netherlands, and Nepal arediscussed. Finally, areas for additional research are proposed,including further definition of washback, motivation and performance,the role of educational explanatory setting, research methodology,learner perceptions, and factors. A 39-item bibliography isappended. -

An Exploration Into What Promotes Or Hinders Beneficial English Test Washback on Teaching and Learning

Doctor of Education Dissertation Title: AN EXPLORATION INTO WHAT PROMOTES OR HINDERS BENEFICIAL ENGLISH TEST WASHBACK ON TEACHING AND LEARNING By Martin Murray Student number: 0039713437 Principal Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Shirley O’Neill Associate Supervisors: Dr. Sang-Soon Park (from 2012) Dr. Kathryn Young (before 2012) June 2013 Faculty of Education, University of Southern Queensland Abstract Ethical English language testing requires an ongoing effort to improve the quality of English test item design. It also requires the identification of what factors might encourage or obstruct positive washback and impact. The advantages and disadvantages of summative high-stakes English tests compared to feasible alternative forms of assessment should also be considered. For instance, an evaluative review of this research suggests the greater appropriateness of multiple medium-stakes formative English assessments over high-stakes summative English tests for students at the case study school. This case study explores the washback phenomenon and related impact phenomenon at one CMI (Chinese Medium of Instruction) secondary school in Hong Kong in order to find out what promotes or hinders beneficial English test washback and impact on teaching and learning at this school and includes a comparison between a new and a long established high-stakes English test. Another focus of this research is the lower academic performance and lower English language proficiency levels of students from lower socio-economic backgrounds. A total of 256 student participants completed questionnaires; 147 student participants took part in group interviews; and 7 teacher participants took part in individual interviews. A total of 23 lesson observations occurred as well as one English SBA (School-based Assessment) assessing session and one group tutorial. -

Code-Mixing and Literal Translation in Nepal's English Newspapers

NELTA Code-Mixing and literal translation in Nepal’s English newspapers Sagar Poudel Tribhuvan University, Nepal Abstract This study examines the texts published in English newspapers in Nepal to find out the code mixing and literal translation of Nepali language. For the study, the data were taken from the secondary sources. Mainly two English newspapers, The Himalayan Times and The Kathmandu Post published in Nepal were taken as the sources of the data purposively. Code mixing is the use of code from one language into another language in the course of using it in communication. Similarly, literal translation is translating the source language text into the target language text with the equivalence of structure, lexicon and morphology. Such code mixing and literal translation brings variation into target language. The study found out that the codes, which are associated with religion, particular culture, local context and situations are mixed with English language. Similarly, the popular expressions among the Nepalese context were found literally translated. Keywords: Code-mixing, literal translation, context, social situation, culture communities are improvised and Introduction marginalized. As a result, linguistic minorities have remained socially Nepal is a multiethnic, multicultural and excluded from harnessing national multilingual country. It is small in area, benefits in the fields such as politics, but has complex cultural diversity economy, education, employment and so including linguistic plurality. The on. Despite its foreign language status, number of languages spoken in the English language is increasingly used in country varies in different census reports. Nepalese context. It is used in almost all However, 123 languages are officially sectors such as education, trade, tourism, recognised by CBS (2011). -

(JWEEP) Hybridity in Nepalese English

Journal of World Englishes and Educational Practices (JWEEP) ISSN: 2707-7586 DOI: 10.32996/jweep Website: https://al-kindipublisher.com/index.php/jweep/index Hybridity in Nepalese English Shankar Dewan1* and Chandra Kumar Laksamba, PhD2 1Lecturer, Department of English, Sukuna Multiple Campus, Sundarharaincha, Morang, Nepal 2Adjunct Professor, Faculty of Social Sciences and Education, Nepal Open University, Manbhawan, Lalitpur, Nepal Corresponding Author: Shankar Dewan, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: December 3, 2020 With its unprecedented spread globally, English has been diversified, nativized, and Accepted: December 11, 2020 hybridized in different countries. In Nepal, English is code-mixed or hybridized as a Volume: 2 result of its contact with the local languages, the bilinguals’ creativity, and the Issue: 6 nativization by Nepalese English speakers. This qualitative content analysis paper DOI: 0.32996/jweep.2020.2.6.2 attempts to describe hybridity in Nepalese English by bringing the linguistic examples from two anthologies of stories, two novels, five essays and two articles written in KEYWORDS English by Nepalese writers, one news story published in the English newspaper, advertisements/banners, and diary entries, which were sampled purposively. The Nepalese English, language present study showed that hybridity is found in affixation, reduplication, contact, hybridity, bilinguals’ compounding, blending, neologisms, and calques. Pedagogically, speakers of creativity, nativization Nepalese English can -

The 2015 Pansig Journal Narratives: Raising the Happiness Quotient

The 2015 PanSIG Journal Narratives: Raising the Happiness Quotient Edited & Published by JALT PanSIG Proceedings Editor-in-Chief Gavin Brooks Doshisha University Editors Mathew Porter (Fukuoka Jo Gakuin University) Donna Fujimoto (Osaka Jogakuin University) Donna Tatsuki (Kobe City University of Foreign Studies.) Layout and Design by Gavin Brooks Message from the editors: The 14th Annual PanSIG Conference was held at Kobe City University of Foreign Studies on May 16th and 17th, 2015. The theme of the conference was, “Narratives: Raising the Happiness Quotient.” This was a collaborative effort from 26 Special Interest Groups (SIGs) within the Japan Association for Language Teaching (JALT). The conference was highly successful and participants were able to attend presentations on a variety of topics from a wide spectrum in the fields of language teaching and learning. With this year conference the name of the post conference publication has been changed to the 2015 PanSIG Journal to reflect the work that the authors’ put into their papers. With a blind peer review process and dedicated reviewing and editing committees, along with motivated and professional authors, the quality of the papers submitted to the post conference publication is consistently very high. The same is true for the papers that have been included in the 2015 PanSIG Journal. This year’s publication is a representative effort from the conference in Kobe and 30 papers from a number of different SIGs on a diverse range of topics were accepted for publication in this year’s volume. These include papers that focus on both research topics and teaching practices and serve to highlight the effort and creativity of the participants of the conference and the members of the SIGs involved. -

The Criterion: an International Journal in English ISSN-0976-8165

www.the-criterion.com The Criterion: An International Journal in English ISSN-0976-8165 English in Multilingual and Cross-cultural Context: Exploring Opportunities and Meeting the Challenges Dr Anil S Kapoor Associate Professor Smt. R R H Patel Mahila Arts College Vijapur, Mehsana Gujarat. The proposed paper endeavours to analyse the role of English language in growing economies, like India, and transforming societies like Nepal. It also attempts to establish that English language has become the vehicle of transformation and an objective means to interpret the numerous cross-cultural contexts within the pluralistic societies. The paper proposes that if the linguistic pre-eminence of English, as a foreign language, is maintained it may affect numerous indigenous native languages/paroles and ultimately disturb the traditional fabric of the ancient cultures. The paper does not suggest that the English language should be dissuaded but it surely seeks to endorse the need to promote English as a more acceptable native language, expressing the hue and taste of the region, in any multilingual and cross-cultural context. The English language has flourished and developed in multilingual and cross- cultural environments. It has become the indisputable world language, owing largely to its status as a link language in multilingual and pluralistic societies. The main reasons for the growth of English may be attributed to the rise and fall of the British Colonial rule, the imminent linguistic void in the immediate post colonial era that required a lingua franca to fill the hiatus and in the more resent times the role of English as the language of modernity, Science, technology, knowledge and development. -

Vol. II Issue IV, Oct. 2013 1 CRITICAL REFLECTIONS on SOUTH ASIAN

New Academia (Print ISSN 2277-3967) (Online ISSN 2347-2073) Vol. II Issue IV, Oct. 2013 1 CRITICAL REFLECTIONS ON SOUTH ASIAN ENGLISH: A LITERARY PERSPECTIVE Mitul Trivedi Research Scholar H M Patel Institute of English Training and Research Sardar Patel University Vallabh Vidyanagar Anand, Gujarat. INDIA Introduction The subtle investigation into the idea and the ideology of globalization constitutes and is constituted around the scholarly consensus of English language being a global means of communication, representation, reception and comprehension. It has, therefore, been referred to and accepted as ‘world language’ – ‘lingua franca of the modern era’ (David Graddol, 1997). However, it needs to be stressed that globalization of English has fundamentally raised the questions of ‘legitimacy’ and ‘standardization’ of the language. It has been researched and debated over the last few decades whether English can be circumscribed within a British or American form since there are multiple varieties of English languages clearly observable in various different cultural contexts. These are often caused by the constant and continuous language shifts through domesticization/nativization and hybridization as these multiple cultural contexts feed back into the language.The focal point of departure of the present study is to investigate into sociocultural, historical, linguistic and stylistic resonances of English languages in the light of South Asian literature in English. Moreover, the present study aims to examine the contemporary South Asian literature in English not merely as a localized creative constructs but as a representation of ‘South Asianness’ in its textual, contextual as well as conceptual histrionics. The contemporary literary constructs in South Asian region seem to cease, partially though, the depiction of postcolonial thematics; however, they adequately represent their own ‘self’ into the language that it has subtly and necessarily nativized to fulfill its creative impulse. -

A Look Into the Local Pedagogy of an English Language Classroom in Nepal

LTR18310.1177/1362168813510387Language Teaching ResearchTin 510387research-article2013 LANGUAGE TEACHING Article RESEARCH Language Teaching Research 2014, Vol. 18(3) 397 –417 A look into the local pedagogy © The Author(s) 2013 Reprints and permissions: of an English language sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1362168813510387 classroom in Nepal ltr.sagepub.com Tan Bee Tin The University of Auckland, New Zealand Abstract English language teaching (ELT) currently occurring in diverse social settings points to the need to locate ELT in its social context. Many researchers have highlighted the need to explore local vernacular practices, in particular ELT practices in peripheral contexts. The present study investigates events in an English language classroom at a Nepalese public college, using ethnographic observations and interviews. The article describes local practices that have emerged to match the contextual particularities of this classroom. Although localized practices are idiosyncratic, they have coherence within the macrocosm of language teacher education. Vernacular practices and local knowledge are under-represented in both ELT theories and language teacher education. The findings of the study will help understand classroom teaching practice and competence of teachers in ‘peripheral’ contexts as well as help raise ‘relevant doubts and questions’ (Bowers, 1986, p. 407) regarding established ELT theories and practices. Keywords Centre and periphery, English language teaching, ethnographic research, local pedagogy, peripheral participation, social context, vernacular practices I Introduction The global spread of English and English language teaching (ELT) to much of the world has stimulated increased attention to social context, and the need to understand how English is learnt and taught in diverse contexts. -

Multilingual Writers' Perceptions and Use of L1 in a U.S. Composition Class

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects Capstone Projects 2017 Multilingual Writers’ Perceptions and Use of L1 in a U.S. Composition Class: A Case Study of Nepalese Students Shyam Bahadur Pandey Minnesota State University, Mankato Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons Recommended Citation Pandey, S. B. (2017). Multilingual Writers’ Perceptions and Use of L1 in a U.S. Composition Class: A Case Study of Nepalese Students [Master’s thesis, Minnesota State University, Mankato]. Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds/696/ This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Multilingual Writers’ Perceptions and Use of L1 in a U.S. Composition Class: A Case Study of Nepalese Students By Shyam Bahadur Pandey A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language Minnesota State University, Mankato Mankato, Minnesota April 2017 Date: 04/07/2017 This thesis paper has been examined and approved. -

Varieties of English 2

KLAM.6185.cp02.019-036 5/17/06 5:25 PM Page 19 Varieties of English 2 CHAPTER PREVIEW Chapter 2 establishes a context for the discussions of English structure in later chapters by viewing English as a continuum of dialects and styles that contrast with each other in pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar. Regional, social, and international dialects reflect who speakers are and where they come from geographically and socially. CHAPTER GOALS At the end of this chapter, you should be able to •Notice language differences in everyday usage. • Understand the difference between regional and social dialects. • Recognize that Standard American English provides a relatively uniform speech variety. Prior study of English grammar has usually left students with the impression that English is or ought to be uniform. Teachers and textbooks have often given students the idea that, in an ideal world, everyone would speak and write a uniform “proper” English, with little or no variation from an agreed-upon stan- dard of correctness. We do not want to give you that impression, for in fact it is the normal con- dition of English and of every other language to vary along a number of dimen- sions. Efforts to put the language (or its speakers) in a linguistic straightjacket by insisting on conformity at all times to a uniform standard are doomed to fail, for they go against the very nature of language: to be flexible and responsive to a variety of conditions related to its users and their purposes. ISBN: 0-558-13856-X 19 Analyzing English Grammar, Fifth Edition, by Thomas P. -

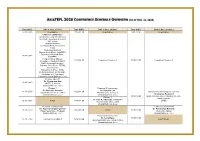

Asiatefl 2020 Full Presentation Schedule

ASIATEFL 2020 CONFERENCE SCHEDULE OVERVIEW (AS OF NOV. 22, 2020) DAY 1: NOV 27, 2020 Time (KST) DAY 1: Nov. 27 (Fri.) Time (KST) DAY 2: Nov. 28 (Sat.) Time (KST) DAY 3: Nov. 29 (Sun.) 12:00-13:00 Registration 12:00-13:00 Registration 9:00-10:00 Registration OPENING CEREMONY Moderators: Judy Yin (General Secretary, AsiaTEFL) & Furo D (MC Robot) Opening Address Joo-Kyung Park (ConFerence Chair) Welcoming Address Jihyeon Jeon (Pres., AsiaTEFL) Fuad Abdul Hamied (Pres., 13:00-13:40 AsiaTEFL) Congratulatory Address Jae-jung Lee (Superintendent, 13:00 - 14:00 Concurrent Session 3 10:00-12:00 Concurrent Session 6 BOE, Gyeonggi-Province) DeboraH SHort (Pres., TESOL International) Daniel Perrin (Pres., AILA) Welcoming Dance PerFormance “Hwagwan-mu,” Ara Dance Company (Grand Ballroom, Live) Keynote Speech Dr. Young-gon Kim 13:40-14:10 (NIIED, S. Korea) (Grand Ballroom, Live) Plenary 1 Featured 2 (concurrent) Dr. Christine Coombe Dr. Hyoshin Lee 14:10-15:00 13:20-14:00 (Dubai Men's College, UAE) (Konkuk Univ., S. Korea) Assessment Workshop (concurrent) (Grand Ballroom, Live) (Grand Ballroom, Live) Christopher Redmond 10:00-12:00 (East Asia Assessment Solutions Team, Plenary 3 British Council) Dr. Paul Kei Matsuda (Hologram) 15:00-15:10 Break 14:00-14:50 (209B) (Arizona State Univ., USA) (Grand Ballroom, Live) Featured 1 (concurrent) Featured 5 (concurrent) Dr. Supong Tangkiengsirisin Dr. Panchanan Mohanty 15:10-15:50 14:50-15:00 Break 11:20-12:00 (THammasat Univ., THailand) (GLA Univ., India) (Grand Ballroom, Live) (Grand Ballroom, Live) Featured 3 (concurrent) Dr. Tariq Elyas 12:00 - 13:00 15:10-17:10 Concurrent Session 1 15:00-15:40 Lunch Break (King Abdulaziz Univ., Saudi Arabia) (Grand Ballroom, Live) Time (KST) DAY 1: Nov. -

Languages of the World

Languages of the World Country Languages/Dialects Country Languages/Dialects Kenya Swahili, Kikuyu and African Languages, English Afghanistan Pushtu, Dari Korea Korean, English Albania Albanian, Greek Kiribati I-Kiribati, English Algeria Arabic, French Kuwait Arabic, Farsi, English Angola Portuguese, Banty Laos Lao, Mong, Chinese dialects Argentina Spanish, Indian Languages Latvia Latvian Armenia Armenian Lebanon Arabic, Armenian, French, English Australia English, Aboriginal and Community languages, Auslan Liberia English, Dialects of Niger - Congo (Deaf Sign Language) Libya Arabic, Hamitic, Italian, English Austria German Lithuania Lithuanian Bahamas English, English & French Creole Macau Portuguese, Cantonese Bahrain Arabic, Farsi, Urdu Malaysia Bahasa Malaysia, Chinese dialects English, Tamil Bangladesh Bengali, English Malta Maltese, English Belgium Flemish, French, German Mauritius Mauritan, French, Creole-English, Hindi Bolivia Spanish, Aymara, Quechua Mexico Spanish Bosnia Bosnian, Serbian, Croatian Morocco Arabic, French, Berber Dialects Brazil Portuguese, Amerindian Languages Mongolia Mongolian, Khala Brunei English, Malay Bulgaria Bulgarian, Romany, Turkish Namibia Afrikaans, English, Bantu Burma Burmese, English Nepal Nepalese. English Burundi Kirundi French Netherlands Dutch, Flemish Byelorussia Byelorussian New Caledonia French, Melanesian-Polynesian Dialects New Zealand English, Maori Cambodia Khmer & dialects, Chinese dialects, English, French Nicaragua Spanish, English, Indian Languages Canada English, French Nigeria