Rage Against the Regime: Niche-Regime Interactions in the Societal Embedding of Plant-Based Milk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

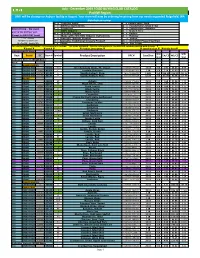

December 2019 FOOD BUYING CLUB CATALOG Pacnw Region UNFI Will Be Closing Our Auburn Facility in August

July - December 2019 FOOD BUYING CLUB CATALOG PacNW Region UNFI will be closing our Auburn facility in August. Your store will now be ordering/receiving from our newly expanded Ridgefield, WA distribution center. n = Contains Sugar F = Foodservice, Bulk s = Artificial Ingredients G = Foodservice, Grab n' Go BASICS Pricing = the lowest 4 = Sulphured D = Foodservice, Supplies _ = 100% Organic K = Gluten Free price at the shelf per unit. H = 95%-99% Organic b = Kosher (Except for FIELD DAY items) : = Made with 70%-94% Organic Ingredients d = Holiday * "DC" Column T = Specialty, Natural Product , = Vegan NO CODE= All Warehouses U = Specialty, Traditional Grocery Product m = NonGMO Project Verified W = PacNW - Seattle, WA C = Ethnic w = Fair Trade For placing a SPECIAL ORDER - It is necessary to include: *THE PAGE NUMBER, Plus the information in the BOLDED columns marked with Arrows "▼" * ▼Brand ▼ ▼Item # ▼ ▼ Product Description ▼ ▼ Case/Unit Size ▼ ▼Whlsle Price▼ Indicates BASICS Items WS/ SRP/ Dept Brand DC Item # Symbols Product Description UPC # Case/Size EA/CS WS/CS Brand Unit Unit Indicates Generic BULK Items BULK BULK BAKINGBAKING GOODSGOODS BULK BAKING GOODS 05451 HKnw Dk Chocolate Chips, FT, Vegan 026938-073442 10 LB EA 6.91 69.06 8.99 BULK BAKING GOODSUTWR 40208 F Lecithin Granules 026938-402082 5 LB EA 7.18 35.90 9.35 BULK BAKING GOODSGXUTWR 33140 F Vanilla Extract, Pure 767572-831288 1 GAL EA 336.90 336.90 439.45 BULK BAKING GOODSGUTWR 33141 F Vanilla Extract, Pure 767572-830328 32 OZ EA 95.08 95.08 123.99 BULK BEANSBEANS BULK -

Food Forests: Their Services and Sustainability

Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development ISSN: 2152-0801 online https://foodsystemsjournal.org Food forests: Their services and sustainability Stefanie Albrecht a * Leuphana University Lüneburg Arnim Wiek b Arizona State University Submitted July 29, 2020 / Revised October 22, 2020, and February 8, 2021 / Accepted Febuary 8, 2021 / Published online July 10, 2021 Citation: Albrecht, S., & Wiek, A (2021). Food forests: Their services and sustainability. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 10(3), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2021.103.014 Copyright © 2021 by the Authors. Published by the Lyson Center for Civic Agriculture and Food Systems. Open access under CC-BY license. Abstract detailed insights on 14 exemplary food forests in Industrialized food systems use unsustainable Europe, North America, and South America, practices leading to climate change, natural gained through site visits and interviews. We resource depletion, economic disparities across the present and illustrate the main services that food value chain, and detrimental impacts on public forests provide and assess their sustainability. The health. In contrast, alternative food solutions such findings indicate that the majority of food forests as food forests have the potential to provide perform well on social-cultural and environmental healthy food, sufficient livelihoods, environmental criteria by building capacity, providing food, services, and spaces for recreation, education, and enhancing biodiversity, and regenerating soil, community building. This study compiles evidence among others. However, for broader impact, food from more than 200 food forests worldwide, with forests need to go beyond the provision of social- cultural and environmental services and enhance a * Corresponding author: Stefanie Albrecht, Doctoral student, their economic viability. -

The Greifswalder Theory of Strong Sustainability and Its Relevance for Policy Advice in Germany and the EU

Sustainability Science – The Greifswalder Theory of Strong Sustainability and its relevance for policy advice in Germany and the EU Ralf Döring* , Barbara Muraca 1 *Johann Heinrich von Thünen - Federal Institute for Rural Areas, Forestry and Fisheries, Germany Abstract The Greifswald approach was developed over many years in the co-operation of environmental philosophers and ecological economists. The theory combines normative arguments on our responsibilities for current and future generations (intra- and intergenerational justice), the conceptual debate on weak vs. strong sustainability, a new concept for natural capital with practical applications in three sectors: fisheries, agriculture and climate change policy. It was developed as an answer to the increasingly vague understanding of the sustainability concept in the political arena, which gives politicians the possibility of subsuming under it all sorts of different programs and strategies. A sharper definition of the concept is needed that offers a non-arbitrary orientation ground for action to end the further loss of essential parts of natural capital without becoming too rigid and exclusive of differences. In this paper we give firstly a short overview about the philosophical background of the theory and about the conceptual debate on weak and strong sustainability. Secondly, we depict our concept of Natural Capital, which draws on Georgescu-Roegen’s systematic framework of fund, stock, services, and flows and focuses on a central characteristic of nature: its (re)productivity. Accordingly, natural capital consists of living funds, non-living funds, and stocks. This differentiation offers a helpful ground for identifying specific preservation goals for the different parts of natural capital and can be successfully employed in the advice for policy makers (as it has been the case with the German Advisory Council for the Environment over a decade). -

NON-DAIRY MILKS 2018 - TREND INSIGHT REPORT It’S on the Way to Becoming a $3.3 Billion Market, and Has Seen 61% Growth in Just a Few Years

NON-DAIRY MILKS 2018 - TREND INSIGHT REPORT It’s on the way to becoming a $3.3 billion market, and has seen 61% growth in just a few years. Non-dairy milks are the clear successor to cow (dairy) milk. Consumers often perceive these products as an answer to their health and wellness goals. But the space isn’t without challenges or considerations. In part one of this two- part series, let’s take a look at the market, from new product introductions to regulatory controversy. COW MILK ON THE DECLINE Cow milk (also called dairy milk) has been on the decline since 2012. Non-dairy milks, however, grew 61% in the same period. Consumers are seeking these plant-based alternatives that they believe help them feel and look better to fulfill health and wellness goals. Perception of the products’ health benefits is growing, as consumers seek relief from intolerance, digestive issues and added sugars. And the market reflects it. Non-dairy milks climbed 10% per year since 2012, a trend that’s expected to continue through 2022 to become a $3.3 billion-dollar market.2 SOY WHAT? MEET THE NON-DAIRY MILKS CONSUMERS CRAVE THREE TREES UNSWEETENED VANILLA ORGANIC ALMONDMILK Made with real Madagascar vanilla ALMOND MILK LEADS THE NON-DAIRY MILK bean, the manufacturer states that the CATEGORY WITH 63.9% MARKET SHARE drink contains more almonds, claims to have healthy fats and is naturally rich and nourishing with kitchen-friendly ingredients. As the dairy milk industry has leveled out, the non-dairy milk market is growing thanks to the consumer who’s gobbling up alternatives like almond milk faster than you can say mooove. -

Challenges for Integration of Sustainability Into Engineering Education

AC 2012-4565: CHALLENGES FOR INTEGRATION OF SUSTAINABIL- ITY INTO ENGINEERING EDUCATION Dr. Qiong Zhang, University of South Florida Qiong Zhang is an Assistant Professor in civil and environmental engineering at the University of South Florida (USF). She received a Ph.D. in environmental engineering from Michigan Tech. Prior to joining the faculty at USF in 2009, she served as the Operations Manager of the Sustainable Future Institute at Michigan Tech. Dr. Linda Vanasupa, California Polytechnic State University Dr. James R. Mihelcic, University of South Florida James R. Mihelcic is a professor of civil and environmental engineering and state of Florida 21st Century World Class Scholar at the University of South Florida. He directs the Peace Corps master’s international program in civil and environmental engineering (http://cee.eng.usf.edu/peacecorps). Mihelcic is a Past President of the Association of Environmental Engineering and Science Professors (AEESP), a member of the EPA Science Advisory Board, and a board-certified member and Board Trustee of the American Academy of Environmental Engineers (AAEE). He is lead author for three textbooks: Fundamentals of Environmental Engineering (John Wiley & Sons, 1999); Field Guide in Environmental Engineering for Development Workers: Water, Sanitation, Indoor Air (ASCE Press, 2009); and, Environmental Engineer- ing: Fundamentals, Sustainability, Design (John Wiley & Sons, 2010). Dr. Julie Beth Zimmerman, Yale University Simona Platukyte, University of South Florida Page 25.294.1 Page c American Society for Engineering Education, 2012 Challenges for Integration of Sustainability into Engineering Education Abstract Due to the relative novelty of the subject of sustainability in the engineering community and its complexity, many challenges remain to successful integration of sustainability education in engineering. -

The Sustainability of Waste Management Models in Circular Economies

sustainability Article The Sustainability of Waste Management Models in Circular Economies Carmen Avilés-Palacios 1 and Ana Rodríguez-Olalla 2,* 1 Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingeniería de Montes, Forestal y del Medio Natural, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, c/José Antonio Novais 10, 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 2 Departamento Economía de la Empresa (ADO), Economía Aplicada II y Fundamentos Análisis Económico, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Paseo de los Artilleros s/n, Vicálvaro, 28032 Madrid, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-910671632 Abstract: The circular economy (CE) is considered a key economic model to meet the challenge of sustainable development. Strenous efforts are focused on the transformation of waste into resources that can be reintroduced into the economic system through proper management. In this way, the linear and waste-producing value chain problems are solved, making them circular, and more sustainable solutions are proposed in those chains already benefiting from circular processes, so that waste generation and waste are reduced on the one hand, and on the other, the non-efficient consumption of resources decreases. In the face of this current tide, there is another option that proposes a certain nuance, based on the premise that, although circular systems promote sustainability, it does not mean that they are in themselves sustainable, given that, in the first place, the effects of CE on sustainable development are not fully known and, on the other hand, the CE model includes the flow of materials, with only scant consideration of the flow of non-material resources (water, soil and energy). -

ANGELICA CAREY Focus: Urban Sustainability a Native from Lynn

Meet Our Students! PATRICK KELLEY JEREMY PRICE Focus: Environmental Quality Focus: Renewable Energy and Efficient Design I completed my undergraduate degree at Hampshire College with a concentration in environmental After completing his undergraduate studies at UMass,(B.S. Sustainable Community Development), and wildlife science. My thesis explored the usage of bird feathers as bioindicators of environmental Jeremy sought to strengthen his ability to effectively facilitate change, and enrolled in the Department ANGELICA CAREY contamination using mass spectrometry in the Cape Cod area. I love the environment and everything of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning’s (LARP) Master of Regional Planning Program. Jeremy Focus: Urban Sustainability that comes with it- wildlife, sunshine, hiking, swimming, and most of all, the beautiful, encouraging is the Peer Undergraduate Advisor/Mentor within LARP and also holds a Graduate Certificate in Climate A native from Lynn, Massachusetts, I attended UMass Amherst for my undergraduate degree in feeling of curiosity that it bestows. I like to think of the environment as the canvas to humankind’s Change and Green infrastructure Planning. Anthropology and Civic Environmentalism, a self-designed major from the BDIC program. After epic masterpiece. To put it simply, there’s really no way to paint without it, and that’s sort of where Looking to further explore the intersection between the environment, planning, and energy, he was graduating in 2012, I was accepted to teach K-5 General Music and 6-8 Choir with Teach for America, sustainability and environmental quality interests me. admitted to the MS3 program where he will concentrate in Renewable Energy and Efficient Design; in the small town of Palestine, Arkansas. -

Biosphere Reserves' Management Effectiveness—A Systematic

sustainability Review Biosphere Reserves’ Management Effectiveness—A Systematic Literature Review and a Research Agenda Ana Filipa Ferreira 1,2,* , Heike Zimmermann 3, Rui Santos 1 and Henrik von Wehrden 2 1 CENSE—Center for Environmental and Sustainability Research, NOVA College of Science and Technology, NOVA University Lisbon, 2829-516 Caparica, Portugal; [email protected] 2 Institute of Ecology, Faculty of Sustainability and Center for Methods, Leuphana University, 21335 Lüneburg, Germany; [email protected] 3 Institute for Ethics and Transdisciplinary Sustainability Research, Faculty of Sustainability, Leuphana University, 21335 Lüneburg, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-21-294-8397 Received: 10 June 2020; Accepted: 2 July 2020; Published: 8 July 2020 Abstract: Research about biosphere reserves’ management effectiveness can contribute to better understanding of the existing gap between the biosphere reserve concept and its implementation. However, there is a limited understanding about where and how research about biosphere reserves’ management effectiveness has been conducted, what topics are investigated, and which are the main findings. This study addresses these gaps in the field, building on a systematic literature review of scientific papers. To this end, we investigated characteristics of publications, scope, status and location of biosphere reserves, research methods and management effectiveness. The results indicate that research is conceptually and methodologically diverse, but unevenly distributed. Three groups of papers associated with different goals of biosphere reserves were identified: capacity building, biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. In general, each group is associated with different methodological approaches and different regions of the world. The results indicate the importance of scale dynamics and trade-offs between goals, which are advanced as important leverage points for the success of biosphere reserves. -

1. What Is Sustainability?

1. What Is Sustainability? Further Reading Articles, Chapters, and Papers Barnofsky, Anthony D. et al. “Approaching a State Shift in Earth’s Biosphere.” Nature (June 7, 2012): 52–58. A review of evidence that, as with individual ecosystems, the global ecosystem as a whole can shift abruptly and irreversibly into a new state once critical thresholds are crossed, and that it is approaching a critical threshold as a result of human influence, and that there is a need to improve the detecting of early warning signs of state shift. Boström, Magnus, ed. “Special Issue: A Missing Pillar? Challenges in Theorizing and Practicing Social Sustainability.” Sustainability: Science, Practice, & Policy, vol. 8 no. 12 (winter 2012). Brown, J. and M. Purcell. “There’s Nothing Inherent about Scale: Political Ecology, the Local Trap, and the Politics of Development in the Brazilian Amazon.” Geoforum, vol. 36 (2005): 607–24. Clark, William C. “Sustainability Science: A Room of Its Own.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 104 no. 6 (February 6, 2007):1737–38. A report on the development of sustainability science as a maturing field with a core research agenda, methodologies, and universities teaching its methods and findings. Costanza, Robert et al. “The Value of the World’s Ecosystem Services and Natural Capital.” Nature, vol. 387 (1997): 253–60. Estimates the current economic value of 17 ecosystem services based on both published research and original calculations. Ehrlich, Paul R., Peter M. Kareiva, and Gretchen C. Daily. “Securing Natural Capital and Expanding Equity to Rescale Civilization.” Nature, vol. 486 (June 2012): 68–73. -

Twelve Factors Influencing Sustainable Recycling of Municipal Solid Waste

Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Reports - Open Reports 2005 Twelve factors influencing sustainable ecyr cling of municipal solid waste in developing countries Alexis Manda Troschinetz Michigan Technological University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds Part of the Civil and Environmental Engineering Commons Copyright 2005 Alexis Manda Troschinetz Recommended Citation Troschinetz, Alexis Manda, "Twelve factors influencing sustainable ecyr cling of municipal solid waste in developing countries ", Master's Thesis, Michigan Technological University, 2005. https://doi.org/10.37099/mtu.dc.etds/277 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds Part of the Civil and Environmental Engineering Commons TWELVE FACTORS INFLUENCING SUSTAINABLE RECYCLING OF MUNICIPAL SOLID WASTE IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES By ALEXIS MANDA TROSCHINETZ A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY 2005 Copyright © Alexis M. Troschinetz 2005 This thesis, “Twelve factors influencing sustainable recycling of municipal solid waste in developing countries," is hereby approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING. DEPARTMENT or PROGRAM: Civil and Environmental Engineering -Signatures- Thesis Advisor: __________________________________________ -

HARNESSING SCIENCE for a SUSTAINABLE FUTURE: NARROWING the POLICY, RESEARCH, and COMMUNITY DIVIDE White Paper Contents

HARNESSING SCIENCE FOR A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE: NARROWING THE POLICY, RESEARCH, AND COMMUNITY DIVIDE White paper Contents I. Mobilizing science for a sustainable future: The sea change needed . 1 Authors Cameron Allen, Adjunct Research II. Key recommendations ............................................. 3 Fellow at Monash Sustainable 2 .1 Recommendations for policymakers . 3 Development Institute and Senior 2 .2 Recommendations for scientists and researchers . 4 Advisor, SDSN TReNDS 2.3 Recommendations for scientific journals and academic institutions . 6 III. Why this matters: A deeper dive into the issues . 8 Jessica Espey, Senior Advisor, SDSN and Director Emeritus, SDSN TReNDS 3 .1 The emerging role and priorities for science to enable a sustainable future . 8 Alyson Marks, Communications 3 .2 Bridging the gap: Interdisciplinary science and hybrid knowledge Manager, SDSN TReNDS systems for practical problem solving . 9 3 .3 Narrowing the science-policy divide: Integration of science, policy, Magdalena Skipper, Editor in Chief, and community . 11 Nature IV. The 'Science for a Sustainable Future' conference . 13 V. Participants in the 'Science for a Sustainable Future' conference Acknowledgments 8th October 2020 . 15 Lucy Frisch, Senior Marketing Manager, VI. References . 16 Springer Nature Laura Helmuth, Editor-in-Chief, Scientific American Nicola Jones, Head of Publishing, Springer Nature SDG Programme Mithu Lucraft, Director of Content Marketing Strategy, Springer Nature Rachel Scheer, Head of US Communications, Springer Nature Thea Sherer, Director, Group Communications, Springer Nature Harnessing science for a sustainable future: Narrowing the policy, research, and community divide springernature .com 1 I . Mobilizing science for a sustainable future: The sea change needed We are facing a time of unprecedented acute, complex, and transboundary sustainable development challenges . -

2Nd World Symposium on Sustainability Science and Research” Is Being Brought to Life

WORLD SYMPOSIUM ON SUSTAINABILITY SCIENCE AND RESEARCH IMPLEMENTING THE 2030 UNITED NATIONS AGENDA FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT SECOND WORLD SYMPOSIUM ON SUSTAINABILITY SCIENCE AND RESEARCH UNIVERSITIES AND SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITIES: MEETING THE GOALS OF THE 2030 UNITED NATIONS AGENDA FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Curitiba, Brazil, 1st-3rd April 2019 1 WORLD SYMPOSIUM ON SUSTAINABILITY SCIENCE AND RESEARCH IMPLEMENTING THE 2030 UNITED NATIONS AGENDA FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT BACKGROUND The United Nations Summit, held on 25 to 27 September 2015 in New York, adopted the post-2015 development agenda and a set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which are outlined in the document "Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development". This Agenda, according to the UN, is a plan of action for people, planet and prosperity, which seeks to strengthen universal peace in larger freedom. It contains 17 Sustainable Development Goals and 169 targets, which demonstrate both a vision and an ambition. It seeks to build on the Millennium Development Goals and complete what these did not achieve. The document "Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development" also clearly show the need for an integrated handling of the three main dimensions of sustainable development: the economic, social and environmental. There is a world consensus in relation to the fact that Sustainability Science -i.e. a branch of science concerned with an integrated view of the three main dimensions of sustainable development, can provide an important contribution in order to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Even though in the past the potential of Sustainability Science has been largely overlooked – some say underestimated – it is clear that it can provide a key contribution to the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SGS) and, more specifically, the realisation of the vision set at the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.