Colin Koyce CARL Research Report 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PME1 Schools List 2019-20

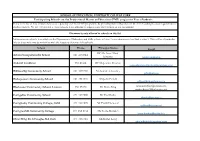

SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK Participating Schools on the Professional Master of Education (PME) 2019/20 for Year 1 Students Below is the list of Post-Primary Schools co-operating on UCC's PME programme by providing School Placement in line with Teaching Council requirements for student teachers. We are very grateful to these schools for continuing to support such a key element of our programme Placement is only allowed in schools on this list. Information on schools is available on the Department of Education and Skills website at http://www.education.ie/en/find-a-school. This will be of particular help to those who may be unfamiliar with the locations of some of the schools. School Phone Principal Name Email DP Ms Anne Marie Ashton Comprehensive School 021 4966044 Hewison [email protected] Ardscoil na nDeise 058 41464 DP Ms Joanne Brosnan [email protected] Ballincollig Community School 021 4871740 Ms Kathleen Lowney [email protected] Bishopstown Community School 021 4544311 Mr John Farrell [email protected] Blackwater Community School, Lismore 058 53620 Mr Denis Ring [email protected]; [email protected] Carrigaline Community School 021 4372300 Mr Paul Burke [email protected] Carrignafoy Community College, Cobh 021 4811325 Mr Frank Donovan [email protected] Carrigtwohill Community College 021 485 3488 Ms Lorna Dundon [email protected] Christ King SS, S Douglas Rd, Cork 021 4961448 Ms Richel Long [email protected] Christian Brothers College, Cork 021 4501653 Mr. David -

Learning Neighbourhoods Pilot Programme

LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS PILOT PROGRAMME BALLYPHEHANE & KNOCKNAHEENY 2015–16 CONTENTS CONTENTS 1. Background to Learning Neighbourhoods 4 2. Activities during the Pilot Year 9 2.1 UCC Learning Neighbourhood Lectures 10 2.2 Lifelong Learning Festival 12 2.2.1 ‘The Free University’ 12 2.2.2 Schools Visit to ‘The Free University’ 13 2.2.3 Ballyphehane Open Morning and UNESCO Visit 13 2.3 Faces of Learning Poster Campaign 14 2.4 Ballyphehane ‘How to Build a Learning Neighbourhood’ 16 2.5 Knocknaheeny and STEAM Education 17 2.6 Media and PR 18 2.7 National and International Collaborations, Presentations and Reports 20 3. Awards and Next Steps 24 This document was prepared by Dr Siobhán O'Sullivan and Lorna Kenny, SECTION 1 Centre for Adult Continuing Education, University College Cork LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS STEERING GROUP Background to Learning Neighbourhoods has been supported during the pilot year by the Learning Neighbourhoods members of the Steering Group • Denis Barrett, Cork Education and Training Board • Lorna Kenny, Learning Neighbourhoods Coordinator, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Willie McAuliffe, Learning Cities Chair • Clíodhna O’Callaghan, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Siobhán O’Dowd, Ballyphehane Togher Community Development Project • Dr Siobhán O’Sullivan, Learning Neighbourhoods Coordinator, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Dr Séamus O’Tuama, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Nuala Stewart, City Northwest Quarter Regeneration, Cork City Council What is a Learning Neighbourhood? A Learning Neighbourhood is an area that has an ongoing commitment to learning, providing inclusive and diverse learning opportunities for whole communities through partnership and collaboration. 2 LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS SECTION 1 / BACKGROUND TO LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS In September 2015, the UNESCO Institute for 25) and also exhibits persistent socio-economic Residents of Lifelong Learning presented Cork with a Learning deprivation. -

UCC Access Programme External Evaluation

University College Cork Access Programme EXTERNAL EVALUATION University College Cork Access Programme EXTERNAL EVALUATION University College Cork Access Programme Evaluation report Cynthia Deane Options Consulting May 2003 Contents Executive summary 1. Introduction p09 1.1 Aims of evaluation p09 1.2 Evaluation methodology p11 2. Outline description of Access programme p13 2.1 Schools programme p14 2.2 Special admissions procedure p29 2.3 Post entry support time p34 2.4 Promotional literature and web site p43 2.5 Staff development p45 3. Feedback from programme participants p50 3.1 Focus group of current Access p50 Programme students 3.2 Questionnaire to current Access students p54 3.3 Interview with group of prospective Access p59 students attending Easter school 3.4 Focus group of principals and teachers p61 from programme linked schools 3.5 Interview with UCC Admissions Officer p68 4. Conclusions and recommendations p72 4.1 Main strengths of the UCC Access Programme p72 4.2 Recommendations for the future p77 Appendices Appendix 1 Schools involved with the Access programme, and the years in which they joined Appendix 2 Special admissions procedure Appendix 3 Questionnaire for students March 2003 Executive Summary This independent evaluation aimed to assess the effectiveness, impact, and sustainability of the UCC Access Programme, which has been in operation since 1996. The evaluation focused on the implementation of the project over a three- year period from 1999 to 2002. It is essentially qualitative in nature, including a description of programme activities and feedback from participants. The key outcomes of the Access Programme are described, and issues and options for the future are identified. -

Cork Learning Neighbourhoods Contents

CORK LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS CONTENTS CONTENTS 1. Background to Learning Neighbourhoods 4 2. Learning Neighbourhood Activities 2016: Ballyphehane and Knocknaheeny 9 (POSTER) How to build a Learning Neighbourhood? 20 3. Learning Neighbourhood Activities 2017: Mayfield & Togher 24 4. Media and PR, National & International Collaborations 32 5. Awards 38 This document was prepared by Dr Siobhán O'Sullivan and Lorna Kenny, Centre for Adult Continuing Education, University College Cork LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS STEERING GROUP Learning Neighbourhoods has been supported by the members of the Steering Group: • Denis Barrett, Cork City Learning Coordinator, formerly Cork Education and Training Board SECTION 1 • Deirdre Creedon, CIT Access Service • Sarah Gallagher, Togher Youth Resilience Project • Lorna Kenny, Learning Neighbourhoods Coordinator, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Willie McAuliffe, Learning Cities Chair • Clíodhna O’Callaghan, Adult Continuing Education, UCC Background to • Siobhán O’Dowd, Ballyphehane Togher Community Development Project • Liz O’Halloran, Mayfield Integrated Community Development Project/Mayfield Community Adult Learning Project C.A.L.P. Learning Neighbourhoods • Sandra O’Meara, Cork City Council RAPID • Sinéad O’Neill, Adult & Community Education Officer, UCC • Dr Siobhán O’Sullivan, Learning Neighbourhoods Coordinator, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Dr Séamus O’Tuama, Adult Continuing Education, UCC • Nuala Stewart, City Northwest Quarter Regeneration, Cork City Council A particular word of thanks to Sara Dalila Hočevar, who worked with Learning Neighbourhoods on an ERASMUS placement in 2017. What is a Learning Neighbourhood? Cork Learning City defines a Learning Neighbourhood as an area that has an ongoing commitment to learning, providing inclusive and diverse learning opportunities for whole communities through partnership and collaboration. 2 LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS SECTION 1 / BACKGROUND TO LEARNING NEIGHBOURHOODS In September 2015, the UNESCO Institute for Knocknaheeny in the north of the city. -

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK SPORTS STRATEGY 2019–2022 Vision the Globally Renowned Go-To University for Sport and Physical Activity in Ireland

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK SPORTS STRATEGY 2019–2022 Vision The globally renowned go-to university for sport and physical activity in Ireland Purpose Realise and unleash the potential of UCC sport and physical activity Mantra Pride on our chest. Belief in our heart. Sport in our bones. UCC SPORTS STRATEGY 2019 – 2022 CONTENTS Foreword 3 UCC Sports Strategy: Summary 4 Timeline 2019–2022 6 Introduction 8 UCC Sports Strategy Planning and Consultation Process 10 UCC Sports Strategy Context 11 Vision For Sport and Physical Activity in UCC 19 Strategic Priorities 21 2 PRIDE ON OUR CHEST. BELIEF IN OUR HEART. SPORT IN OUR BONES. UCC SPORTS STRATEGY 2019 – 2022 3 FOREWORD University College Cork has a deep and proud history of between our clubs and coaches; the Department of sporting achievement, and strong ambitions for the Sport and Physical Activity; Mardyke Arena, our sporting future. The importance of sport goes much further than facilities; and a range of academic disciplines and empowering people with health and wellbeing – sport research activities. The scholarship of sport, in the teaches life lessons of confidence, teamwork, respect, context of UCC’s tradition of research and teaching ambition, discipline, integrity and it provides a source of excellence, will sharpen our edge to push the boundaries great enjoyment. Through sport we learn that, no matter of sport through education, research and innovation. what the result, we must persevere and not give up. It gives me great pleasure to introduce this strategy for UCC is a connected university, and sport plays an sport, which sets out 27 specific actions to be important role in connecting student and alumni implemented across six priority areas over the short, communities, and engaging with the wider community. -

Designing and Implementing Neighborhoods of Learning in Cork’S Unesco Learning City Project

DESIGNING AND IMPLEMENTING NEIGHBORHOODS OF LEARNING IN CORK’S UNESCO LEARNING CITY PROJECT Séamus Ó Tuama, Ph.D.1 Siobhán O’Sullivan, Ph.D.2 ABSTRACT: Cork, the Republic of Ireland’s second most populous city, is one of 12 UNESCO Learning Cities globally. Becoming a learning city requires a sophisticated audit of education, learning and other socio-economic indicators. It also demands that cities become proactively engaged in delivering to the objectives set by the Beijing Declaration on Building Learning Cities which was adopted at the first UNESCO International Conference on Learning Cities in Beijing (2013) and the Mexico City Statement on Sustainable Learning Cities from the second conference in Mexico City (2015). The UNESCO learning city approach lays heavy emphasis on lifelong learning and social inclusion. In addressing these two concerns Cork city is piloting the development of two Learning Neighborhoods. The pilots are a collaboration between the City Council, University College Cork and Cork Education and Training Board who will work with the learning and education organizations and residents in each area to promote, acknowledge and show case active local lifelong learning. This paper looks at the context and design of these Learning Neighborhoods. Keywords: Learning City, Neighborhood Learning, UNESCO, Cork Cork: A UNESCO Learning City Cork City was granted the UNESCO Learning City Award at the second UNESCO International Conference on Learning Cities in Mexico City in September 2015. A total of twelve cities were granted the award viz. Melton (Australia), Sorocaba (Brazil), Beijing (China), Bahir Dar (Ethiopia), Espoo (Finland), Cork (Ireland), Amman (Jordan), Mexico City (Mexico), Ybycuí (Paraguay), Balanga (Philippines), Namyangju (Republic of Korea) and Swansea (United Kingdom). -

Cork City Attractions (Pdf)

12 Shandon Tower & Bells, 8 Crawford Art Gallery 9 Elizabeth Fort 10 The English Market 11 Nano Nagle Place St Anne’s Church 13 The Butter Museum 14 St Fin Barre’s Cathedral 15 St Peter’s Cork 16 Triskel Christchurch TOP ATTRACTIONS IN CORK C TY Crawford Art Gallery is a National Cultural Institution, housed in one of the most Cork City’s 17th century star-shaped fort, built in the aftermath of the Battle Trading as a market since 1788, it pre-dates most other markets of it’s kind. Nano Nagle Place is an historic oasis in the centre of bustling Cork city. The The red and white stone tower of St Anne’s Church Shandon, with its golden Located in the historic Shandon area, Cork’s unique museum explores the St. Fin Barre’s Cathedral is situated in the centre of Cork City. Designed by St Peter’s Cork situated in the heart of the Medieval town is the city’s oldest Explore and enjoy Cork’s Premier Arts and Culture Venue with its unique historic buildings in Cork City. Originally built in 1724, the building was transformed of Kinsale (1601) Elizabeth Fort served to reinforce English dominance and Indeed Barcelona’s famous Boqueria market did not start until 80 years after lovingly restored 18th century walled convent and contemplative gardens are salmon perched on top, is one of the city’s most iconic landmarks. One of the history and development of: William Burges and consecrated in 1870, the Cathedral lies on a site where church with parts of the building dating back to 12th century. -

Blackpool Village Regeneration Strategy

Commissioned Study for Respond! Housing Association 2013-2014 Blackpool Village Regeneration Strategy EDUCATION REPORT February 2014 Respond! is Ireland’s leading housing who have lived for long periods in hostels, Respond! employ over 300 people who association, established in 1982. Respond! temporary and insecure accommodation. work creatively within a framework believe in delivering housing for social of shared values and social goals. The investment rather than for financial profit Respond! seek to create positive futures for in-house team is spread throughout and provide housing for almost 20,000 people by alleviating poverty and creating the country and includes architects, residents around Ireland. Homes are vibrant, socially integrated communities. accountants, technical services officers, provided for individuals, families, This is achieved by providing access psychologists, nurses, as well as the elderly, people who are living with a to education, childcare, community educational, research, finance, legal disability and also for some of the most development programmes, housing and administrative, IT, childcare and resident vulnerable groups in society including those other supports. support personnel. Copyright: Respond! Housing Association 2014 All rights reserved. First published by: Respond! Housing Association, Airmount, Dominick Place, Waterford Lo-call: 0818 357901 Web: www.respond.ie E-mail: [email protected] Respond! Housing Association is a company limited by guarantee and registered in Dublin, Ireland. Registration number 90576. Respond! comply with the Governance code for community, voluntary and charitable organisations in Ireland. Charity number CHY 6629. Registered office: Airmount, Dominick Place, Waterford, Ireland. Directors: Joe Horan (Chairman) Michael O’Doherty, Tom Dilleen, Brian Hennebry, Deirdre Keogh and Patrick Cogan, ofm. -

Integrated Result System

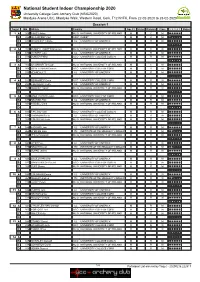

National Student Indoor Championship 2020 University College Cork Archery Club (NSIC2020) Mardyke Arena UCC, Mardyke Walk, Western Road, Cork, T12 N1FK, From 22-02-2020 to 23-02-2020 Session 1 Target Bib Athlete Country Age Cl. Subclass Division Class 1 2 3 4 5 Status 1 A 100 FAHEY Adam NUIG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND M C M B 032 MCCAFFREY Carl GUEST GUEST M G M C 035 MCGREEVY Charlie UL UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK M R M D 2 A 101 RUSSELL-COWEN Shannon NUIG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND W C W B 036 VICKERY Luke UL UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK M R M C 016 DUNLEA Phillip UCD UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DUBLIN M R M D 3 A 102 O'CONNOR Turlough NUIG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND M C M B 009 O'CALLAGHAN Cormac UCC UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK M R M C 039 KENNEALY Tj UL UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK M R M D 4 A 012 REINHARDT Carla UCC UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK W R W B 033 COUGHLAN Keith UL UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK M R M C 103 MOONEY Róisín NUIG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND W R W D 5 A 003 O'SULLIVAN Brendan UCC UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK M R M B 037 KEATING Finn UL UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK M R M C 104 RIDDELL Chris NUIG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND M R M D 6 A 015 TAN Jing Yuan UCD UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DUBLIN M R M B 038 CHAPMAN Sarah UL UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK W R W C 105 COUGHLAN Josh NUIG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND M R M D 7 A 040 HIGGINS Liam UL UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK M R M B 069 O' BRIEN Liam ITC INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY CARLOW M R M C 106 PFETZING Oisín NUIG NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND M R M D 8 A 042 WEST Eva UL UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK W R W B 070 KEOGH Kieran ITC -

Thinking of Selling?

6,000 FREE THINKING OF SELLING? Also available at outlets in Mayfield, Upper Glanmire, Whites Cross, Watergrasshill, Glounthaune, Little Island, Carrigtwohill, Lisgoold, Carrignavar, Whitechurch & Knockraha. LOCAL COMPANY THE DIFFERENCE IS WE DELIVER Issue 3 - March 2015 GLOBAL AUDIENCE www.glanmireareacork.com e-mail- [email protected] M:086 8294713 SUPPORT US ON GAP OF DUNLOE WALK IN AID OF CANCER RESEARCH - SATURDAY MARCH 28th. Joe Organ Rena Guildea On Saturday March 28th, in the Joe Organ Auctioneers morning, at 8.30 on the dot, we will Mobile: 086 6013222 meet and leave from the library in Hazelwood by coach, to go to Killar- Phone: 021 2428620 ney and on to Kate Kearney’s. email [email protected] www.joeorganauctioneers.ie We will have time for a coffee/tea Office 2B Crestfield Centre, Glanmire. and a scone before walking the 11 km through the Gap of Dunloe; this takes between 2 and 2 and a half hours and leads us to Lord Brandon’s cottage. Time for something to eat, either bring your own or you can avail of what is available in the line of soup and sandwiches (and their delicious fruitcake). At 2 o’clock the boatmen will be ready to take us down the river and along the lake to Muckross House. The coach will be there to meet us and take us back to Hazelwood for about 6.30. The cost is a minimum of 40 euro, if you wish to give us more, it will be much appreciated of course! This will cover coach and boat, all food and drink you will have to pay for yourself separately. -

COMHAIRLE CATHRACH CHORCAÍ CORK CITY COUNCIL 14Th February 2019 REPORT on WARD FUNDS PAID in 2018 the Following Is a List of P

COMHAIRLE CATHRACH CHORCAÍ CORK CITY COUNCIL 14th February 2019 REPORT ON WARD FUNDS PAID IN 2018 The following is a list of payees who received Ward Funds from Members in 2018: Payee Amount 37TH CORK SCOUT GROUP €500.00 38TH/40TH BALLINLOUGH SCOUT GR €750.00 3RD CORK SCOUTS TROOP €800.00 43RD/70TH CORK BISHOPSTOWN SCO €150.00 53RD CORK SCOUT TROOP €500.00 5TH CORK LOUGH SCOUTS €275.00 87TH SCOUT GROUP €100.00 AGE ACTION IRELAND €500.00 AGE LINK MAHON CDP €350.00 ARD NA LAOI RESIDENTS ASSOC €700.00 ART LIFE CULTURE LTD €100.00 ASCENSION BATON TWIRLERS €550.00 ASHDENE RES ASSOC €700.00 ASHGROVE PARK RESIDENTS ASSOCI €150.00 ASHMOUNT RESIDENTS ASSOCIATION €600.00 AVONDALE UTD F.C. €1,050.00 AVONMORE PARK RESIDENTS ASSOCI €700.00 BAILE BEAG CHILDCARE LTD €700.00 BALLINEASPIG,FIRGROVE,WESTGATE €400.00 BALLINLOUGH COMM. MIDSUMMER FE €1,300.00 BALLINLOUGH MEALS ON WHEELS €150.00 BALLINLOUGH PITCH AND PUTT CLU €200.00 BALLINLOUGH RETIRED PEOPLE'S N €100.00 BALLINLOUGH RETIREMENT CLUB €200.00 BALLINLOUGH SCOUT GROUP €600.00 BALLINLOUGH SUMMER SCHEME €1,450.00 BALLINLOUGH YOUTH CLUB €400.00 BALLINURE GAA CLUB €300.00 BALLYPHEHANE COMMUNITY ASSOC €500.00 BALLYPHEHANE COMMUNITY YOUTH E €300.00 BALLYPHEHANE DISTRICT PIPE BAN €400.00 BALLYPHEHANE GAA CLUB €800.00 BALLYPHEHANE GAA CLUB JUNIOR S €100.00 BALLYPHEHANE HURLING & FOOTBAL €500.00 BALLYPHEHANE LADIES CLUB €125.00 BALLYPHEHANE LADIES FOOTBALL C €1,250.00 BALLYPHEHANE MEALS ON WHEELS €250.00 BALLYPHEHANE MENS SHED €1,475.00 BALLYPHEHANE PIPE BAND €250.00 BALLYPHEHANE TOGHER CDP €150.00 BALLYPHEHANE -

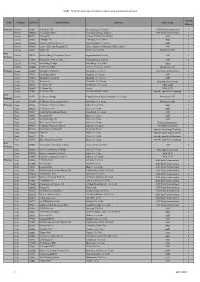

NCSE 13/14 Full List of Special Classes Attached to Mainstream Schools

NCSE 13/14 full list of special classes attached to mainstream schools No of Type County Roll No School Name Address Class Type Classes Primary Carlow 13105L St Brigid's NS Muinebeag, Co Carlow ASD Early Intervention 2 Carlow 18424G St. Joseph’s BNS St. Joseph’s Road, Carlow ASD Early Intervention 2 Carlow 04077I Grange NS Grange, Tullow, Co Carlow ASD 2 Carlow 17514C Clonegal NS Clonegal, Co Carlow ASD 1 Carlow 18183K Queen of the Universe NS Muinebheag, Co Carlow ASD 2 Carlow 20295K Carlow Educate Together NS Unit 5, Shamrock Business Park, Carlow ASD 2 Carlow 14837L Ballon NS Ballon, Co Carlow Moderate GLD 1 Post Carlow 70430U Muine Bheag Vocational School Bagenalstown Carlow ASD 1 Primary Carlow 61150N Presentation De La Salle Bagenalstown, Carlow ASD 2 Carlow 61130H Knockbeg College Knockbeg, Co Carlow ASD 1 Carlow 61141K St Leo's College Carlow Town, Co Carlow Moderate GLD 1 Primary Cavan 19008V Mullagh Central NS Mullagh, Co. Cavan ASD Early Intervention 1 Cavan 17625L Knocktemple NS Virginia, Co Cavan ASD 3 Cavan 19008V Mullagh Central NS Mullagh, Co. Cavan ASD 1 Cavan 12312L Darley NS Cootehill, Co Cavan Hearing Impairment 1 Cavan 18059J St Annes NS Bailieboro, Co Cavan Mild GLD 1 Cavan 08490N St Clares NS Cavan Mild GLD 1 Cavan 17326B St. Felim's NS Farnham Street, Cavan Specific Speech & Language 2 Post Cavan 61051L St Clares College Virginia Road, Ballyjamesduff, Co Cavan Moderate GLD 1 Primary Cavan 70350W St. Bricin's Vocational School Belturbet, Co Cavan Moderate GLD 1 Primary Clare 20041C St Senan's Primary School Kilrush,