Five Forgotten Trail-Blazers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Game Summaries:IMG.Qxd

Sunday, September 12, 2010 Green Bay Packers 27 Lincoln Financial Field Philadelphia Eagles 20 Clad in their Kelly green uniforms in honor of the 1960 NFL cham- 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Pts pions, the Philadelphia Eagles made a valiant comeback attempt Green Bay 013140-27 but fell just short in the final minutes of the season opener vs. Green Philadelphia 30710-20 Bay. Philadelphia fell behind 13-3 at half and 27-10 in the 4th quar- ter and lost four key players along the way: starting QB Kevin Kolb Phila - D.Akers, 45 FG (8-26, 4:00) (concussion), MLB Stewart Bradley (concussion), FB Leonard GB - M.Crosby, 49 FG (10-43, 5:31) Weaver (ACL), and C Jamaal Jackson (triceps). But behind the arm GB - D. Driver, 6 pass from Rodgers (Crosby) (11-76, 5:33) and legs of back-up signal caller Michael Vick, the Eagles rallied to GB - M.Crosby, 56 FG (7-39, 0:41) make the score 27-20 late in the 4th quarter. In fact, they took over GB - J.Kuhn, 3 run (Crosby) (10-62, 4:53) possession at their own 24-yard-line with 4:13 to play and drove to Phila - L.McCoy, 12 run (Akers) (9-60, 4:12) the GB42 before Vick was tackled short of a first down on a 4th-and- GB - G.Jennings, 32 pass from Rodgers (Crosby) (4-51, 2:28) 1 rushing attempt to seal the Packers victory. After the Eagles took Phila - J.Maclin, 17 pass from Vick (Akers) (9-79, 3:39) a 3-0 lead after an interception by Joselio Hanson, Green Bay took Phila - D.Akers, 24 FG (9-45, 3:31) control over the remainder of the first half. -

Tony Adamle: Doctor of Defense

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 24, No. 3 (2002) Tony Adamle: Doctor of Defense By Bob Carroll Paul Brown “always wanted his players to better themselves, and he wanted us known for being more than just football players,” Tony Adamle told an Akron Beacon Journal reporter in 1999. In the case of Adamle, the former Cleveland Browns linebacker who passed away on October 8, 2000, at age 76, his post-football career brought him even more honor than captaining a world championship team. Tony was born May 15, 1924, in Fairmont, West Virginia, to parents who had immigrated from Slovenia. By the time he reached high school, his family had moved to Cleveland where he attended Collinwood High. From there, he moved on to Ohio State University where he first played under Brown who became the OSU coach in 1941. World War II interrupted Adamle’s college days along with those of so many others. He joined the U.S. Air Force and served in the Middle East theatre. By the time he returned, Paul Bixler had succeeded Paul Brown, who had moved on to create Cleveland’s team in the new All-America Football Conference. Adamle lettered for the Buckeyes in 1946 and played well enough that he was selected to the 1947 College All-Star Game. He started at fullback on a team that pulled off a rare 16-0 victory over the NFL’s 1946 champions, the Chicago Bears. Six other members of the starting lineup were destined to make a mark in the AAFC, including the game’s stars, quarterback George Ratterman and running back Buddy Young. -

2 Den at Chi 08 16 2003 Fli

Denver Broncos vs Chicago Bears Saturday, August 16, 2003 at Memorial Stadium BEARS BEARS OFFENSE BEARS DEFENSE BRONCOS No Name Pos WR 80 D.White 83 D.Terrell 87 J.Elliott LE 93 P.Daniels 99 J.Tafoya 63 C.Demaree No Name Pos 10 Stewart,Kordell QB WR 16 E.Shepherd 18 J.Gage LT 92 T.Washington 70 A.Boone 71 I.Scott 1 Elam,Jason K 11 Barnard,Brooks P 11 Beuerlein,Steve QB 12 Chandler,Chris QB LT 69 M.Gandy 60 T.Metcalf 63 P.Lougheed RT 98 B.Robinson 94 K.Traylor 72 E.Grant 12 Adams,Charlie WR 15 Forde,Andre WR LG 64 R.Tucker 73 S.Grice 62 T.Vincent DT 73 T.LaFavor 67 T.Benford 13 Madise,Adrian WR 16 Shepherd,Edell WR 14 Jackson,Nate WR 17 Sauter,Cory QB C 57 O.Kreutz 74 B.Robertson 67 J.Warner RE 96 A.Brown 97 M.Haynes 76 B.Setzer 15 Rice,Frank WR 18 Gage,Justin WR RG 58 C.Villarrial 67 J.Warner 68 B.Anderson WLB 53 W.Holdman 55 M.Caldwell 59 J.Odom 16 Plummer,Jake QB 19 Thurmon,Elijah WR 17 Jackson,Jarious QB 2 Edinger,Paul K RG 76 J.Grzeskowiak 71 J.Soriano MLB 54 B.Urlacher 52 B.Howard 62 J.Schumacher 2 Rolovich,Nick QB 20 Williams,Roosevelt CB RT 78 A.Gibson 79 S.Edwards 75 M.Colombo SLB 90 B.Knight 91 L.Briggs 55 M.Caldwell 20 Jackson,Marlion RB 21 McQuarters,R.W. CB 21 Kelly,Ben CB 22 Hicks,Maurice RB TE 88 D.Clark 89 D.Lyman 85 J.Gilmore LCB 21 R.McQuarters 20 R.Williams 46 J.Goss 22 Griffin,Quentin RB 23 Azumah,Jerry CB TE 46 B.Fletcher 49 M.Afariogun 82 J.Davis LCB 26 T.McMillon 24 E.Joyce 23 Middlebrooks,Willie CB 24 Joyce,Eric CB 24 O'Neal,Deltha CB 25 Gray,Bobby SS TE 48 R.Johnson RCB 23 J.Azumah 33 C.Tillman 39 T.Gaines 25 Ferguson,Nick -

Als, Lions on Sunday Huskies $5,000 and Suspended Kris Sem Balerus for the Re M Ainder of the Season

12 - The Prince George Citizen - Friday, November 19,1999 S p o r t s CIAU fines Huskies OTTAW A (CP) — The CIAU has fined the Saskatchewan Als, Lions on Sunday Huskies $5,000 and suspended Kris Sem balerus for the re m ainder of the season. The H uskies allow ed Sem balerus, an by DAN RALPH W EST DIVISION academ ically ineligible athlete, to play in the Canada W est Canadian Press C algary Stam peders at B.C. Lions conference cham pionship. Dave Ritchie and Jim Barker w ill be reluc Calgary looked dom inant in its 30-17 sem ifi m tant couch potatoes on Sunday. nal w in over Edm onton last w eekend, but w ill ^ Ritchie, the W innipeg Blue Bom bers coach be w ithout outstanding running back Kelvin United Native Nations Local72 presents1 \ and football-operations director, and Barker, Anderson (sprained ankle). Rookie Rock Pre the Toronto Argonauts head coach, w ill dis ston w ill try to replace the CFL’s No. 3 rusher Sports Dinner & Auction 0 patch their headsets and parkas Sunday and (1,256 yards) an overall leader in com bined c j j* « . with keynote speaker: COalB Sn3C K revert back to football fan status w hen the yards (2,258) and yards from scrim m age Saturday, Jan 29th, 2000 (C CFL’s division finals kick off. (1,820). Still, quarterback Dave D ickenson T7ie CoastInn o f the North A » Barker, whose team dropped a 27-6 sem ifi has no shortage of w eapons, w ith slot backs Cocktails at 6:00 pm % nal decision last w eek to H am ilton, likes the Allen Pitts, the W est D ivision nom inee as the Dinner at 7:00 pm . -

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 7, No. 5 (1985) THE 1920s ALL-PROS IN RETROSPECT By Bob Carroll Arguments over who was the best tackle – quarterback – placekicker – water boy – will never cease. Nor should they. They're half the fun. But those that try to rank a player in the 1980s against one from the 1940s border on the absurd. Different conditions produce different results. The game is different in 1985 from that played even in 1970. Nevertheless, you'd think we could reach some kind of agreement as to the best players of a given decade. Well, you'd also think we could conquer the common cold. Conditions change quite a bit even in a ten-year span. Pro football grew up a lot in the 1920s. All things considered, it's probably safe to say the quality of play was better in 1929 than in 1920, but don't bet the mortgage. The most-widely published attempt to identify the best players of the 1920s was that chosen by the Pro Football Hall of Fame Selection Committee in celebration of the NFL's first 50 years. They selected the following 18-man roster: E: Guy Chamberlin C: George Trafton Lavie Dilweg B: Jim Conzelman George Halas Paddy Driscoll T: Ed Healey Red Grange Wilbur Henry Joe Guyon Cal Hubbard Curly Lambeau Steve Owen Ernie Nevers G: Hunk Anderson Jim Thorpe Walt Kiesling Mike Michalske Three things about this roster are striking. First, the selectors leaned heavily on men already enshrined in the Hall of Fame. There's logic to that, of course, but the scary part is that it looks like they didn't do much original research. -

06FB Guide P151-190.Pmd

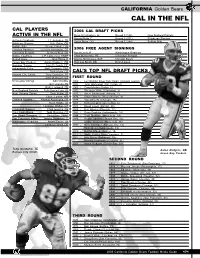

CALIFORNIA Golden Bears CAL IN THE NFL CAL PLAYERS 2006 CAL DRAFT PICKS ACTIVE IN THE NFL Ryan O’Callaghan, OL Round 5 (136) New England Patriots Marvin Philip, C Round 6 (201) Pittsburgh Steelers Arizona Cardinals J.J. Arrington, TB Aaron Merz, OG Round 7 (248) Buffalo Bills Baltimore Ravens Kyle Boller, QB Buffalo Bills Wendell Hunter, LB Carolina Panthers Lorenzo Alexander, DT 2006 FREE AGENT SIGNINGS Cincinnati Bengals Deltha O’Neal, CB David Lonie, P Washington Redskins Dallas Cowboys L.P. Ladouceur, SNAP Chris Manderino, FB Cincinnati Bengals Detroit Lions Nick Harris, P Donnie McCleskey, SAF Chicago Bears Green Bay Packers Aaron Rodgers, QB Harrison Smith, DB Detroit Lions Houston Texans Jerry DeLoach, DE Indianapolis Colts Matt Giordano, SAF Tarik Glenn, OT CAL’S TOP NFL DRAFT PICKS Kansas City Chiefs Tony Gonzalez, TE John Welbourn, OT FIRST ROUND Minnesota Vikings Adimchinobe 1952 - Les Richter (New York Yanks, 2nd pick overall) Echemandu, TB 1953 - John Olszewski (Chi. Cards, 4) Ryan Longwell, PK 1965 - Craig Morton (Dallas, 6) New England Patriots Tully Banta-Cain, LB 1972 - Sherman White (Cincinnati, 2) New Orleans Saints Scott Fujita, LB 1975 - Steve Bartkowski (Atlanta, 1) Chase Lyman, WR 1976 - Chuck Muncie (New Orleans, 3) Oakland Raiders Nnamdi Asomugha, CB 1977 - Ted Albrecht (Chicago, 15) Ryan Riddle, LB 1981 - Rich Campbell (Green Bay, 6) Langston Walker, OT 1984 - David Lewis (Detroit, 20) Pittsburgh Steelers Chidi Iwuoma, CB 1988 - Ken Harvey (Phoenix, 12) Saint Louis Rams Todd Steussie, OT 1993 - Sean Dawkins (Indianapolis, -

Illinois ... Football Guide

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign !~he Quad s the :enter of :ampus ife 3 . H«H» H 1 i % UI 6 U= tiii L L,._ L-'IA-OHAMPAIGK The 1990 Illinois Football Media Guide • The University of Illinois . • A 100-year Tradition, continued ~> The University at a Glance 118 Chronology 4 President Stanley Ikenberrv • The Athletes . 4 Chancellor Morton Weir 122 Consensus All-American/ 5 UI Board of Trustees All-Big Ten 6 Academics 124 Football Captains/ " Life on Campus Most Valuable Players • The Division of 125 All-Stars Intercollegiate Athletics 127 Academic All-Americans/ 10 A Brief History Academic All-Big Ten 11 Football Facilities 128 Hall of Fame Winners 12 John Mackovic 129 Silver Football Award 10 Assistant Coaches 130 Fighting Illini in the 20 D.I.A. Staff Heisman Voting • 1990 Outlook... 131 Bruce Capel Award 28 Alpha/Numerical Outlook 132 Illini in the NFL 30 1990 Outlook • Statistical Highlights 34 1990 Fighting Illini 134 V early Statistical Leaders • 1990 Opponents at a Glance 136 Individual Records-Offense 64 Opponent Previews 143 Individual Records-Defense All-Time Record vs. Opponents 41 NCAA Records 75 UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 78 UI Travel Plans/ 145 Freshman /Single-Play/ ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN Opponent Directory Regular Season UNIVERSITY OF responsible for its charging this material is • A Look back at the 1989 Season Team Records The person on or before theidue date. 146 Ail-Time Marks renewal or return to the library Sll 1989 Illinois Stats for is $125.00, $300.00 14, Top Performances minimum fee for a lost item 82 1989 Big Ten Stats The 149 Television Appearances journals. -

1956 Topps Football Checklist

1956 Topps Football Checklist 1 John Carson SP 2 Gordon Soltau 3 Frank Varrichione 4 Eddie Bell 5 Alex Webster RC 6 Norm Van Brocklin 7 Packers Team 8 Lou Creekmur 9 Lou Groza 10 Tom Bienemann SP 11 George Blanda 12 Alan Ameche 13 Vic Janowicz SP 14 Dick Moegle 15 Fran Rogel 16 Harold Giancanelli 17 Emlen Tunnell 18 Tank Younger 19 Bill Howton 20 Jack Christiansen 21 Pete Brewster 22 Cardinals Team SP 23 Ed Brown 24 Joe Campanella 25 Leon Heath SP 26 49ers Team 27 Dick Flanagan 28 Chuck Bednarik 29 Kyle Rote 30 Les Richter 31 Howard Ferguson 32 Dorne Dibble 33 Ken Konz 34 Dave Mann SP 35 Rick Casares 36 Art Donovan 37 Chuck Drazenovich SP 38 Joe Arenas 39 Lynn Chandnois 40 Eagles Team 41 Roosevelt Brown RC 42 Tom Fears 43 Gary Knafelc Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Joe Schmidt RC 45 Browns Team 46 Len Teeuws RC, SP 47 Bill George RC 48 Colts Team 49 Eddie LeBaron SP 50 Hugh McElhenny 51 Ted Marchibroda 52 Adrian Burk 53 Frank Gifford 54 Charles Toogood 55 Tobin Rote 56 Bill Stits 57 Don Colo 58 Ollie Matson SP 59 Harlon Hill 60 Lenny Moore RC 61 Redskins Team SP 62 Billy Wilson 63 Steelers Team 64 Bob Pellegrini 65 Ken MacAfee 66 Will Sherman 67 Roger Zatkoff 68 Dave Middleton 69 Ray Renfro 70 Don Stonesifer SP 71 Stan Jones RC 72 Jim Mutscheller 73 Volney Peters SP 74 Leo Nomellini 75 Ray Mathews 76 Dick Bielski 77 Charley Conerly 78 Elroy Hirsch 79 Bill Forester RC 80 Jim Doran 81 Fred Morrison 82 Jack Simmons SP 83 Bill McColl 84 Bert Rechichar 85 Joe Scudero SP 86 Y.A. -

Drafting NFL Wide Receivers: Hit Or Miss? by Amrit Dhar

Drafting NFL Wide Receivers: Hit or Miss? By Amrit Dhar I. Introduction The Detroit Lions, an NFL franchise known for regularly fielding poor football teams, attained a cumulative win/loss record of 48-128 from the 2000-2010 seasons. Many football analysts believe that part of their failure to create quality football teams is due to their aggression in selecting wide receivers early in the NFL draft, and their inability to accurately choose wide receivers that become elite NFL players. Over the past decade, they have spent four of their 1st round draft picks on wide receivers, and only two of those picks actually remained with the Lions for more than two years. The Lions represent an extreme example, but do highlight the inherent unpredictability in drafting wide receivers that perform well in the NFL. However, teams continue to draft wide receivers in the 1st round like the Lions have done as the NFL has evolved into a “passing” league. In 2010 alone, 59 percent of NFL play-calls were called passes, which explains the need for elite wide receivers in any franchise. In this report, I want to analyze whether the factors that teams believe are indicative of wide receiver effectiveness in the NFL actually do lead to higher performance. The above anecdote suggests that there is a gap between how NFL teams value wide receivers in the draft and how well they perform in the NFL. By conducting statistical analyses of where wide receivers were chosen in the NFL draft against how they performed in the NFL, I will be able to determine some important factors that have lead to their success in the NFL, and will be able to see whether those factors correspond to the factors that NFL draft evaluators believe are important for success in the NFL. -

Final Rosters

Rosters 2001 Final Rosters Injury Statuses: (-) = OK; P = Probable; Q = Questionable; D = Doubtful; O = Out; IR = On IR. Baltimore Hownds Owner: Zack Wilz-Knutson PLAYER POSITION NFL TEAM INJ STARTER RESERVE ON IR There are no players on this team's week 17 roster. Houston Stallions Owner: Ian Wilz PLAYER POSITION NFL TEAM INJ STARTER RESERVE ON IR Dave Brown QB ARI - Jake Plummer QB ARI - Tim Couch QB CLE - Duce Staley RB PHI - Ricky Watters RB SEA IR Ron Dayne RB NYG - Stanley Pritchett RB CHI - Zack Crockett RB OAK - Derrick Mason WR TEN - Johnnie Morton WR DET - Laveranues Coles WR NYJ - Willie Jackson WR NOR - Alge Crumpler TE ATL - Dave Moore TE TAM - Matt Stover K BAL - Paul Edinger K CHI - 2001 Final Rosters 1 Rosters Chicago Bears Defense CHI - Pittsburgh Steelers Defense PIT - Carolina Panthers Special Team CAR - Dallas Cowboys Special Team DAL - Dan Reeves Head Coach ATL - Dick Jauron Head Coach CHI - NYC Dark Force Owner: D.J. Wendell NFL ON PLAYER POSITION INJ STARTER RESERVE TEAM IR Aaron Brooks QB NOR - Daunte Culpepper QB MIN - Jeff Blake QB NOR - Bob Christian RB ATL - Emmitt Smith RB DAL - James Stewart RB DET - Jim Kleinsasser RB MIN - Warrick Dunn RB TAM - Cris Carter WR MIN - James Thrash WR PHI - Jerry Rice WR OAK - Travis Taylor WR BAL - Dwayne Carswell TE DEN - Jay Riemersma TE BUF - Jay Feely K ATL - Joe Nedney K TEN - San Francisco 49ers Defense SFO - Defense TAM - 2001 Final Rosters 2 Rosters Tampa Bay Buccaneers Minnesota Vikings Special Team MIN - Oakland Raiders Special Team OAK - Dick Vermeil Head Coach KAN - Steve Mariucci Head Coach SFO - Las Vegas Owner: ?? PLAYER POSITION NFL TEAM INJ STARTER RESERVE ON IR There are no players on this team's week 17 roster. -

Football Bowl Subdivision Records

FOOTBALL BOWL SUBDIVISION RECORDS Individual Records 2 Team Records 24 All-Time Individual Leaders on Offense 35 All-Time Individual Leaders on Defense 63 All-Time Individual Leaders on Special Teams 75 All-Time Team Season Leaders 86 Annual Team Champions 91 Toughest-Schedule Annual Leaders 98 Annual Most-Improved Teams 100 All-Time Won-Loss Records 103 Winningest Teams by Decade 106 National Poll Rankings 111 College Football Playoff 164 Bowl Coalition, Alliance and Bowl Championship Series History 166 Streaks and Rivalries 182 Major-College Statistics Trends 186 FBS Membership Since 1978 195 College Football Rules Changes 196 INDIVIDUAL RECORDS Under a three-division reorganization plan adopted by the special NCAA NCAA DEFENSIVE FOOTBALL STATISTICS COMPILATION Convention of August 1973, teams classified major-college in football on August 1, 1973, were placed in Division I. College-division teams were divided POLICIES into Division II and Division III. At the NCAA Convention of January 1978, All individual defensive statistics reported to the NCAA must be compiled by Division I was divided into Division I-A and Division I-AA for football only (In the press box statistics crew during the game. Defensive numbers compiled 2006, I-A was renamed Football Bowl Subdivision, and I-AA was renamed by the coaching staff or other university/college personnel using game film will Football Championship Subdivision.). not be considered “official” NCAA statistics. Before 2002, postseason games were not included in NCAA final football This policy does not preclude a conference or institution from making after- statistics or records. Beginning with the 2002 season, all postseason games the-game changes to press box numbers. -

Donovan Mcnabb's 11 Seasons with the Eagles Have Mixed Glory and Grief

End of an Era Donovan McNabb’s 11 seasons with the Eagles have mixed glory and grief. GARY BOGDON / Orlando Sentinel At the NFL draft in 1999, Eagles fans make their opinion clear RON CORTES / Staff Photographer on the player the Birds should choose. They booed McNabb. of 37 for 281 yards and 1 April 1999 2003 season touchdown for a QB rating McNabb — the Eagles’ McNabb comes under of 99.0), running (5 rushes No. 1 choice in the NFL attack on ESPN from for 20 yards) and is sacked 4 draft, and second overall political commentator times, but what people will pick — is booed by Philly Rush Limbaugh, who says remember is a long pass play fans who wanted the team McNabb is overrated, and from the Eagle 25-yard line, to draft Ricky Williams, that the news media — when McNabb hits DeSean the 1998 Heisman Trophy- anxious to have a black Jackson with a spiral for a winning running back for the quarterback succeed in the 60-yard gain. Despite having University of Texas. NFL — gives him a pass and a 28-14 lead when that pass overlooks his failings. was completed, the Eagles 1999 season INSTANT REPLAY lost, 41-37. n Jan. 11, 2004 vs. n Nov. 23, 2008 vs. Ravens: McNabb wins his first game Packers: After going 12-4 McNabb is benched at as a starter, and then starts in the regular season, the halftime after throwing two and loses the next four games Eagles host the Packers in a interceptions and going 8 before being injured before divisional playoff.