The Antitrust Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Very Vintage for Golf Minded Women

PAST CHAMPIONS Year Champion Year Champion 1952 Jean Perry 1982 Lynn Chapman 1953 Joanne Gunderson 1983 Lil Schmide 1954 Joanne Gunderson 1984 Sue Otani 1955 Jean Thorpen 1985 Sue Otani 1956 Jenny Horne 1986 Cathy Daley 1957 Becky Brady 1987 Ann Carr 1958 Mary Horton 1988 Brenda Cagle 1959 Joyce Roberts. 1989 Michelle Campbell 2012 GSWPGA City 1960 Mildred Barter 1990 Linda Rudolph 1961 Joyce Roberts 1991 Gerene Lombardini 1962 Pat Reeves 1992 Rachel Strauss Championship 1963 Pat Reeves 1993 Janet Best 1964 Joyce Roberts 1994 Rachel Strauss August 6, 7, & 8 1965 Mary Ann George 1995 Deb Dols 1966 Olive Corey 1996 Jennifer Ederer Hosted by Auburn Ladies Club 1967 Borgie Bryan 1997 Jennifer Ederer 1968 Fran Welke 1998 Sharon Drummey 1969 Fran Welke 1999 Rachel Strauss at Auburn Golf Course 1970 Carole Holland 2000 Rachel Strauss 1971 Edee Layson 2001 Marian Read 1972 Anita Cocklin 2002 Rachel Strauss 1973 Terri Thoreson 2003 Rachel Strauss Very Vintage 1974 Carole Holland 2004 Mimi Sato 1975 Carole Holland 2005 Rachel Strauss 1976 Carole Holland 2006 Rachel Strauss 1977 Chris Aoki 2007 Janet Dobrowolski 2008 Rachel Strauss For Golf Minded 1978 Jani Japar 1979 Carole Holland 2009 Rachel Strauss 1980 Lisa Porambo 2010 Cathy Kay 1981 Karen Hansen 2011 Mariko Angeles Women In honor of the Legends Tour participants in the July 29, 2012 event at Inglewood Golf and CC and past women contributors to the game of golf, we are naming the tee boxes for this tournament: Hole #1: JoAnne Carner Hole #10: Nancy Lopez Hole #2: Patty Sheehan Hole #11: Jan Stephenson Hole #3: Lori West Hole #12: Dawn Coe-Jones Hole #4: Elaine Crosby Hole #13: Patti Rizzo To view more GSWPGA History, visit: Hole #5: Shelley Hamlin Hole #14: Elaine Figg-Currier http://www.gswpga.com/museum.htm Hole #6: Jane Blalock Hole #15: Val Skinner For information about the Legends Tour event at Inglewood Golf and CC Hole #7: Sandra Palmer Hole #16: Rosie Jones July 29th, 2012, visit: thelegendstour.com/tournaments_2012_SwingforCure_Seattle Hole #8: Sherri Turner Hole #17: Amy Alcott on the web. -

FOR SHORE the LPGA Tournament Now Known As the ANA Inspiration Has a Rich History Rooted in Celebrity, Major Golf Milestones, and One Special Leap

DRIVING AMBITION In the inaugural tournament bearing her name, Dinah Shore was reportedly more concerned about her “golfing look” than her golfing score. Opposite: In 1986, the City of Rancho Mirage honored the entertainer by naming a street after her. Dinah’s Place, FOR SHORE The LPGA tournament now known as the ANA Inspiration has a rich history rooted in celebrity, major golf milestones, and one special leap. by ROBERT KAUFMAN photography from the PALM SPRINGS LIFE ARCHIVES NE OF THE MOST SERENDIPITOUS Palmolive. Already a mastermind at selling toothpaste and soaps, Foster moments in the history of women’s professional recognized women’s golf as a platform ripe for promoting sponsors — but if golf stems from the day Frances Rose “Dinah” the calculating businessman were to roll the dice, the strategy must provide Shore entered the world. In a twist of fate just a handsome return on the investment. over a half century following leap day, Feb. 29, During this era, famous entertainers, including Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, 1916, the future singer, actress, and television Andy Williams, and Danny Thomas, to name a few, were already marquee personality would emerge as a major force names on PGA Tour events. Without any Hollywood influence on the LPGA behind the women’s sport, leaping into a Tour, Foster enlisted his A-list celebrity, Dinah Shore, whose daytime talk higher stratosphere with the birth of the Colgate-Dinah Shore Winner’s show “Dinah’s Place” was sponsored by Colgate-Palmolive, Circle Oin 1972. to be his hostess. The top-charting female vocalist While it may have taken 13 tenacious female golfers — the likes of Babe of the 1940s agreed. -

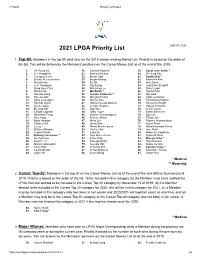

2021 LPGA Priority List JAN-07-2021

1/7/2021 Priority List Report 2021 LPGA Priority List JAN-07-2021 1. Top-80: Members in the top 80 (and ties) on the 2019 season-ending Money List. Priority is based on the order of the list. Ties will be broken by the Members' positions on the Career Money List as of the end of the 2019. 1. Jin Young Ko 30. Caroline Masson 59. Sarah Jane Smith ** 2. Sei Young Kim 31. Azahara Munoz 60. Wei-Ling Hsu 3. Jeongeun Lee6 32. Bronte Law 61. Sandra Gal * 4. Brooke M. Henderson 33. Megan Khang 62. Katherine Kirk 5. Nelly Korda 34. Su Oh 63. Amy Olson 6. Lexi Thompson 35. Ally Ewing 64. Jodi Ewart Shadoff 7. Sung Hyun Park 36. Mi Hyang Lee 65. Stacy Lewis 8. Minjee Lee 37. Mo Martin * 66. Gerina Piller 9. Danielle Kang 38. Suzann Pettersen ** 67. Mel Reid 10. Hyo Joo Kim 39. Morgan Pressel 68. Cydney Clanton 11. Ariya Jutanugarn 40. Marina Alex 69. Pornanong Phatlum 12. Hannah Green 41. Nanna Koerstz Madsen 70. Cheyenne Knight 13. Lizette Salas 42. Jennifer Kupcho 71. Sakura Yokomine 14. Mi Jung Hur 43. Jing Yan 72. In Gee Chun 15. Carlota Ciganda 44. Gaby Lopez 73. Sarah Schmelzel 16. Shanshan Feng 45. Jasmine Suwannapura 74. Xiyu Lin 17. Amy Yang 46. Kristen Gillman 75. Tiffany Joh 18. Nasa Hataoka 47. Mirim Lee 76. Pajaree Anannarukarn 19. Charley Hull 48. Jenny Shin 77. Austin Ernst 20. Yu Liu 49. Nicole Broch Larsen 78. Maria Fernanda Torres 21. Brittany Altomare 50. Chella Choi 79. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE Meunier-Lebouc, Neumann added to fresh&easy Dinah Shore Charity Pro-Am field Event will benefit LA’s BEST and Park Century School RANCHO MIRAGE, Calif., March 15, 2011 – Patricia Meunier-Lebouc, 2003 Kraft Nabisco Championship winner, and Liselotte Neumann, a 13-time Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA) Tour winner, have been added to the field for the inaugural fresh&easy Dinah Shore Charity Pro-Am on April 2, 2011, at Mission Hills Country Club, Palmer Course, in Rancho Mirage, Calif. With the addition of these two players, the 18-player field includes eight LPGA Tour and World Golf Halls of Fame members as well as players who represent 16 Kraft Nabisco Championship wins and a total of 450 LPGA Tour victories. The fresh&easy Dinah Shore Charity Pro-Am was created by Amy Alcott, a three-time Kraft Nabisco Championship winner and member of the LPGA Tour and World Golf Halls of Fame, and Tim Mason, CEO of Fresh & Easy Neighborhood Market and Fresh & Easy Neighborhood Foundation. The event will honor the legacy of Dinah Shore and the 40-year history of champions and stars of the Kraft Nabisco Championship as well as raise awareness and funding for important children’s education initiatives. “I am very excited to have Patricia (Meunier-Lebouc) and Liselotte (Neumann) join our event,” said Alcott. “They complement such a tremendous list of players who are champions and stars of women’s golf. With their support I can’t wait to kick-off the fresh&easy Dinah Shore Charity Pro-Am and celebrate Dinah’s legacy and the 40 years of the Kraft Nabisco Championship.” Previously announced players include Alcott, Donna Andrews, Jane Blalock, Pat Bradley, Donna Caponi, Beth Daniel, Rosie Jones, Betsy King, Nancy Lopez, Meg Mallon, Alice Miller, Alison Nicholas, Sandra Palmer, Patty Sheehan, Hollis Stacy and Kathy Whitworth, the winningest golfer of all time. -

KZG Has Models for All Players Including: Competitive Players

WWW.KZG.COM SEPTEMBER 2017 EDITION _____________________________________________________ IN THIS ISSUE MODELS FOR ALL PLAYERS NEW: LDI IRONS JUNIORS SEPTEMBER MEMORIES KZG has models for all players including: Competitive players, Beginners that need ease of play Seniors who want more oomph in their game Ladies who would prefer a lighter club for greater swing speed Avid golfers Juniors Please visit your KZG Authorized Dealer to discuss your game and your goals. NEW: LDI Irons Do you want irons with more distance? KZG is finding that all levels of players are getting one to two clubs greater distance! The LDI body is cast with our proprietary, heat treated 431 stainless steel. This multi material clubhead provides astonishing distance and remarkable forgiveness. The thin forged 17-4 stainless steel insert not only provides exceptional feel and sound but also makes the LDI KZG's longest iron to date. The larger clubhead is a real confidence booster. A wider, heavier sole aids in launching the ball high, while the deep perimeter weighting makes for an incredibly forgiving golf club. Available In both Left And Right Hand From 4 thru 9 with PW, AW and SW. Go see your KZG dealer and experience the difference for yourself today. Juniors As our children take up the game we need to make sure they have equipment suited for their unique needs. Grandad's clubs with the shafts cut down will only teach poor swing habits which are difficult to unlearn or will make them drop the sport altogether from a lack of success. Something we all wish to avoid. -

LPGA Legends Tour Hits the Northwest the LPGA Tour Made Its Return to the Puget Sound in NW GOLF Area - Well Kind Of

PRESORT STD FREE JULY U.S. Postage PAID COPY 2018 ISSUE THE SOURCE FOR NORTHWEST GOLF NEWS Port Townsend, WA Permit 262 Central Washington has a diverse collection of golf This month Inside Golf Newspaper takes a look the courses in Central Washington area - including places like Moses Pointe in Moses Lake (pictured right). Some of the best desert courses in the state are found here, but there are some lush tree-lined courses as well. See inside this month’s special feature on Central Washington. WHAT’S NEW LPGA Legends Tour hits the Northwest The LPGA Tour made its return to the Puget Sound IN NW GOLF area - well kind of. The LPGA Legends Tour held its first event of the season at the White Horse Golf Club in Kingston with the inaugural Suquamish Clearwater Casino Legends Cup. It might not have been an LPGA Tour event, but Professional tours set to many of the names were familiar and had played at hit the Pacific Northwest the Safeco Classic 20 years ago when it was held at Meridian Valley Country Club in Kent. Professional golf tours will make their annual Players like Sandra Palmer, Jane Blalock and return to the Pacific Northwest during the 2018 golf season. Here’s what is coming to the tee Michelle McGann were some of the familiar names to box in the Northwest this year: tee it up at White Horse. Northwest favorites Joanne • The WinCo Foods Portland Open, a Carner and Wendy Ward also took part. Web.com Tour event, will take place Aug. -

Winter 1979 Vol. 96 No. J Q Call :Jo Convention a Call Lo Come Lo Convention I:$ Teing (Jounded /Or All Y Appa(J

of Kappa Kappa Gamma Winter 1979 Vol. 96 No. J q Call :Jo Convention _A call lo come lo convention i:$ teing (Jounded /or all Y appa(J . Jhe location al Jhe Breaker() _}.jote/, P alm Beach, J!orda, promi(Je(J (Jplendor and elegance a() well a() fine /ood, /riend(Jhip, and /unf Jhe purpo(Je o/ lhe convention i(J lo elect o/ficer(J and lo lraMacl lhe t u(Jine(J(J o/ lhe Jralernil'l. Jt i(J a lime o/ inleraclion telween aclive ani alumnae delegate:$ where ideM are /reel'! (Jhared, common concern:$ can te aired, and accompt(Jhment:$ are rewarded. '/A(Jilor(J are an imporlanl part o/ convention a() all :$hare in lhe workin g() o/ Y appa fappa (jamma. _A:$ lhe man'! chamtered nautdu(J (J'ImtofizM growth, :$0 lhe Y appa · convention wd! re/lect upon the heritage, ponder lhe progre(J(J o/ lhe pre(Jenl, and proiecl the excitement o/ the 80j, lead through the tentative convention (Jchedule, fill out 'lour convention /arm, and make plan:$ now to ioin the Y appa:$ in convention June 19-25, 1980. efo'lal/'1, Jean J./e(J(J We/~, d Y (}eorgia Jraternil'l P,.e(Jident Vermont Colonization The colonization of the University of Mrs. Wiles Converse, Vermont chapter of Kappa Kappa Gamma Fraternity Extension Chairman will take place March 21 and 22, 1980 in Bur 83 Stoneleigh Court lington, Vermont. Please send references to: Rochester, New York 14618 The Key 'Dible of Contents of Kappa Kappa Gamma ALUMNAE EDITOR - Mrs. -

Dan Reeves Moves West

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 20, No. 1 (1998) DAN REEVES MOVES WEST Courtesy of The Pro Football Hall of Fame We were chewing the fat with members of the pro football beat not long ago and the subject of sports news bombshells of the century came up. Nominations were plentiful and discussion was prolonged, but, not surprisingly, no winner was declared. But one nomination is worth recalling to pro football fans. That would be the move of the Cleveland Rams to Los Angeles on January 12, 1946. Owner Dan Reeves forced the move and it was a sports bombshell that has/had prolonged effect not only on professional football, but on the professional sports scene as a whole. This was a shocker for a number of reasons: (1) The Rams less than a month earlier had won the NFL championship: (2) No major league franchise in any sport had ever called a West Coast city home before: (3) Air travel was still in its earlier stages and Los Angeles was 2000 long, hard land miles away from the nearest NFL city: (4) There was a strong tradition for college football in Los Angeles, but no tradition at all for pro football: (5) And most important, Reeves' fellow NFL owners were dead set against the move. But Reeves, who became a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame -- his election to the pro grid shrine undoubtedly came in recognition of the later-proven genius of this move -- was just as determined that his team would not play in Cleveland again. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. IDgher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & HoweU Information Compaiy 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 OUTSIDE THE LINES: THE AFRICAN AMERICAN STRUGGLE TO PARTICIPATE IN PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL, 1904-1962 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State U niversity By Charles Kenyatta Ross, B.A., M.A. -

Firsts in Sports: Winning Stories

Firsts in Sports: Winning Stories by Paul T. Owens Copyright © 2010 by Paul T. Owens. All rights reserved. Published by Myron Publishers. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, transcribed, stored in a retrieval system, or translated into any language, in any form by any means without the written permission of the publisher; exceptions are made for brief excerpts used in published reviews. Published by Myron Publishers 4625 Saltillo St. Woodland Hills, CA 91364 www.myronpublishers.com www.paultowens.com ISBN:978-0-9824675-1-0 Library of Congress Control Number: Printed in the USA This book is available for purchase in bulk by organizations and institutions at special discounts. Please direct your inquiries to [email protected] Edited by Jo Ellen Krumm and Lee Fields. Cover & Interior Design, Typesetting by Lyn Adelstein. 2 What People Are Saying About Firsts in Sports: Winning Stories “I like the way Paul included baseball with his story of football’s first lawsuit.” —Joe DiMaggio, New York Yankees “Firsts in Sports: Winning Stories is timely for today’s pro-football environment, since it explains how the players and owners deal legally. The author takes you “inside” throught the eyes of the referee, with issues one can not get any other way. An interesting as well as educa- tional read.” —Dr. Jim Tunney, NFL Referee 1960-91 “My good friend and great writer.” —Jim Murray, Los Angeles Times Regarding the Torch Relay: “Wouldn’t it be great if we could do this more often. Everyone has come together for this moment, and no one wants it to stop. -

(Restoring the Holt Legacy), 1951-1968 Jack C

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Rollins College: A Centennial History Archives and Special Collections 6-2017 Chapter 09: The cKM ean Era (Restoring the Holt Legacy), 1951-1968 Jack C. Lane Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mnscpts Recommended Citation Lane, Jack C., "Chapter 09: The cKeM an Era (Restoring the Holt Legacy), 1951-1968" (2017). Rollins College: A Centennial History. 3. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mnscpts/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rollins College: A Centennial History by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 CHAPTER 9 RESTORING THE HOLT LEGACY (THE MCKEAN ERA), 1951-1968 Shortly after assuming the office of Acting President, Hugh McKean admitted with refreshing, but troubling, candor: “As a college president, I am a rank amateur. I have the additional handicap of being almost an unwilling one. I taught art at Rollins for twenty years and that is what I should be doing now.”(1) No one who knew McKean would have quarreled with this self-assessment. The question then is: why, from all the administrators and faculty at Rollins College, the anti-Wagner Trustees singled out this inexperienced, self-effacing artist to bring stability back to a college in disarray? There is nothing in the copious Rollins Archival records of this period that would even suggest an answer. In all his years at Rollins, McKean had not been a leader of the faculty nor had he shown any interest in administration. -

U.S& Naval Guantanamo L Base Bay, Cuba

U.S& NAVAL L BASE DEFEX SCHEDULED FOR SATURDAY CHANNEL 8 TO SIGN ON LATE GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA A base-wide Defex (defense exer- TO PERMIT EQUIPMENT INSTALLATION cise) will be held Saturday morning commencing at 6:30 a.m. and ending Channel 8 TV will sign on at 5:55 at about 9:30 a.m. p.m. with "Notes of Interest" next The base alarm will be sounded to week, Monday through Friday, in- signal the end of the Defex but not stead of at the usual sign-on time. the beginning. The reason for the late sign-on All personnel except those speci- is to permit installation of new fically excused by ComNavBase will color equipment. participate in the Defex. The TV schedule on pages 4 and 5 Dependents and other non-essential of today's Gazette reflects the personnel are required to remain in late start of broadcasting. their quarters throughout the exer- cise. All Navy Exchange facilities and KISSINGER SAYS U.S. WILL NOT MAKE the Commissary will be open for business approximately one half 8, 1975 DECISION FOR SOUTH VIETNAM hour after completion of the Defex. F y r WASHINGTON (AP)--U.S. Secretary FALL OF PHNOM PENH DEEPENS SOUTH VIETNAMESE'S UNCERTAINTY of State Henry A. Kissinger said yesterday the United States will not SAIGON (AP)--The fall of Phnom Other politicians linked the fall make the decision for South Vietnam Penh yesterday deepened the sense of Cambodia to American aid policy as to how long it should resist. of uncertainty and despair among and said the same thing might be in However, Kissinger also told the many South Vietnamese for the fu- store for South Vietnam if Congress American Society of Newspaper Edi- ture of their own country.