The Significance of the Edict of Milan, in Edward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Period of Recognition Part 1 Constantine's Basilicas

The Period of Recognition AD 313—476 Surely one of the most important events in history must be the so called Edict of Milan (313), a concordat really, between Constantine in the 2 Western half of the Empire and his co-emperor in the East, Licinius, that recognized all existing religions in the Roman Empire at the time, most especially Christianity, and extended to all of them the freedom of open, public practice. Equally important, subsequently, was Constantine’s pri- vate, yet imperial, patronage of the Christian church. Also, sixty years later, in 390, the emperor Theodosius would declare Christianity the offi- cial religion of the Roman Empire and followers of the ancient pagan rites, criminals. The pagans were soon subjected to the same repression as Christians had been, save violent widespread persecution. The perse- cuted had become the persecutors . Within another hundred years (in 476) the political Empire in the West would collapse and the Christian church would become the sole unifying cultural force among a collection of bar- barian kingdoms. Christianity would go on to dominate the society of Western Europe for the next thousand years. Thus the three sources from which modern Europe sprang were tapped: Greece, Rome, and Christian- ity. Constantine’s Christianity Constantine attributed his defeat of rival Maxentius for the emperorship of the Roman Empire in the 63 The Battle at the Milvian West to the God of the Chris- Bridge tians. He had had a dream or <www.heritage-history.com/www/ heritage.php?R_m... > vision in which his mother’s Christian God told him that he would be victorious if he marched his army under the Christian symbol of the chi rho , the monogram for the name of Jesus Christ. -

Reflection for the 23Rd Sunday of Ordinary Time “Where Two Or Three Are Gathered Together in My Name, There Am I in the Midst

Reflection for the 23rd Sunday of Ordinary Time “Where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them.” Mt 18:20 This quote taken from the last verse of our Gospel reading this Sunday is a gentle but powerful reminder that Christ has given us a community of believers to journey with in this world and in the next. We are not solitary figures of faith taking a lonely journey of faith in this world misunderstood by all we meet. More often than not we might as true followers of Christ feel alone and isolated in a world that is calling us to compromise our beliefs for the comfort of the community at large. May we be true to the example of our fore-fathers in faith who were faith filled believers that would not compromise their beliefs even if it meant certain death. For the first 300 years of the Catholic faith, we as followers of the Son of God were persecuted by the Roman Empire. Just professing faith in Jesus Christ as the Son of God could result in prison and death. The early Church did not just survive this challenging time it thrived. The Church was of course affected by the 300 years of persecution. We can see it in the fact the adult baptism was more common in the early Church then infant baptism. Also, the fact that the early Christians used the catacombs not only to bury the dead by also to celebrate Mass in relative safety, helped develop an appreciation of the relics of the Saints. -

Constantine's Effect on Early Christianity

Constantine’s Effect on Early Christianity Jo Ann Shcall Constantine! When you hear his name, do you think of the power and brutality of the Roman Empire, or do you think of the founding of formalized Christianity? Was Constantine good, bad, a mixture? There’s evidence for each position. Why Consider Constantine? The Orthodox Church regards Constantine as Saint Constantine the Great. He did much for the early Christian church from 306 to 337 while he was the Roman Emperor. Constantine was the first Roman Emperor to claim conversion to Christianity. His declaration of the Edict of Milan in 313 is one of his most important early contributions. This edict declared that Christians (and all other religions) would be tolerated throughout the empire, bringing an end to religious persecution. Constantine called together the first council of Nicaea in 325 with 250 mostly Eastern bishops1 resulting in the Nicene Creed, a statement of faith that attempted to unite disparate Christian communities.2 Constantine built the Church of the Holy Sepulcher at the purported site of Jesus’ tomb, which became the holiest site in Christendom. During his reign, he built many basilicas, repaired churches throughout the empire, relieved clergy of some taxes, supported the Christian church financially3 and saw that Sunday was designated as a day of rest for all citizens. He promoted Christians into political offices. Constantine decided his capitol should be moved to Byzantium. He did extensive building in this city, then renamed it Constantinople. This “new city” was said to be protected by relics of the True Cross, the Rod of Moses, and other holy relics. -

Religious Toleration for All: the Edict of Milan

Religious Toleration for All: The Edict of Milan Constantine and Licinius (313) When I, Constantine Augustus, as well as I, Licinius Augustus, had fortunately met near Mediolanum (Milan), and were considering everything that pertained to the public welfare and security, we thought that among other things which we saw would be for the good of many, that those regulations pertaining to the reverence of the Divinity ought certainly to be made first, so that we might grant to the Christians and to all others full authority to observe that religion which each preferred; whence any Divinity whatsoever in the seat of the heavens may be propitious and kindly disposed to us, and all who are placed under our rule. And thus by this wholesome counsel and most upright provision, we thought to arrange that no one whatever should be denied the opportunity to give his heart to the observance of the Christian religion or of that religion which he should think best for himself, so that the supreme Deity, to whose worship we freely yield our hearts, may show in all things his usual favor and benevolence. Therefore, your Worship should know that it has pleased us to remove all conditions whatsoever, which were in the rescripts formerly given to you officially, concerning the Christians, and now any one of these who wishes to observe the Christian religion may do so freely and openly, without any disturbance or molestation. ... When you see that this has been granted to them by us, your Worship will know that we have also conceded to other religions the right of open and free observance of their worship for the sake of the peace of our times, that each one may have the free opportunity to worship as he pleases; this regulation is made that we may not seem to detract aught from any dignity or any religion. -

TIMELINE of EARLY CHRISTIAN HISTORY: 100 AD to 800 AD C 100 St

TIMELINE OF EARLY CHRISTIAN HISTORY: 100 AD TO 800 AD c 100 St. John dies. End of Apostolic age 107 Ignatius of Antioch martyred 156 Polycarp martyred 161-180 Persecution of Christians increases under Marcus Aurelius c 165 Justin Martyr martyred c 180 Irenaeus of Lyon writes Against Heresies 184 Birth of Origen 250 Persecution of Christians under Decius 253 Death of Origen, shortly after suffering two years of imprisonment and torture 303-312 The Diocletian persecution – the Roman empire’s last, largest and bloodiest persecution of Christians 310 Armenia becomes the first country to adopt Christianity as its official religion. 312 Constantine, at the Battle of Milvian Bridge, experiences vision of the cross carrying the message, In Hoc Signo Vinces ("with this sign, you shall win") 313 Constantine issues the Edict of Milan, providing for the toleration of Christianity and Christians c 323 Eusebius of Caesarea completes Ecclesiastical History 325 First Council of Nicaea (the first ecumenical council) is convened by Constantine. Debate rages over whether Christ is of the "same substance" or "similar substance" to God. The position of Arius, that Christ was of “similar substance” (i.e., that he is a created being), is refuted. Nicene Creed is drawn up, declaring Christ to be "Begotten, not made; of one essence with the Father." 324 Constantinople becomes capital of the Roman Empire 349 Birth of John Chrysostom 354 Birth of Augustine of Hippo 367 Athanasius, in his annual festal letter to the churches of Alexandria, lists the 27 books he believed should constitute the New Testament 380 Theodosius issues the Edict of Thessalonica, declaring Nicene Christianity the official religion of the Roman empire 381 First Council of Constantinople is convened by Theodosius. -

Constantine, the Edict of Milan (313

Constantine, The Edict of Milan (313 CE)1 without molestation…When you see that this has been granted to them Constantine was the son of the Roman Emperor Constantius; he by us, your Worship will know that we have also conceded to other claimed the throne in 306 CE but had to fight several rivals until 324, at religions the right of open and free observance of their worship for the which point he became the supreme Roman Emperor (though he still had co-emperors). According to his biographer Eusebius, Constantine had a sake of the peace of our times, that each one may have the free dream the night before a major battle in which he saw a Christian opportunity to worship as he pleases; this regulation is made we that we symbol and the inscription “conquer by this.” He took it as his battle standard and was victorious. Constantine embraced Christianity in the may not seem to detract from any dignity or any religion. early 300s, and issued this official edict (with his co-emperor Licinius) in Moreover, in the case of the Christians especially we esteemed it 313 CE. When I, Constantine Augustus, as well as I, Licinius Augustus, best to order that if it happems anyone heretofore has bought from our fortunately met near Mediolanurn (Milan), and were considering treasury from anyone whatsoever, those places where they were everything that pertained to the public welfare and security, we thought, previously accustomed to assemble, concerning which a certain decree among other things which we saw would be for the good of many, those had been made -

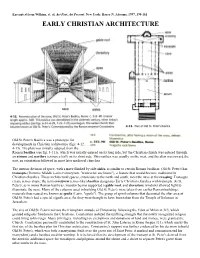

Early Christian Architecture

Excerpted from Wilkins, et. al, Art Past, Art Present. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997, 190-161 EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE Old St. Peter's Basilica was a prototype for developments in Christian architecture (figs. 4-12, 4-13). The plan was initially adapted from the Roman basilica (see fig. 3-111), which was usually entered on its long side, but the Christian church was entered through an atrium and narthex (entrance hall) on its short side. This narthex was usually on the west, and the altar was toward the east, an orientation followed in most later medieval churches. The interior division of space, with a nave flanked by side aisles, is similar to certain Roman basilicas. Old St. Peter's has transepts (from the Middle Latin transseptum, "transverse enclosure"), a feature that would become traditional in Christian churches. These architectural spaces, extensions to the north and south, meet the nave at the crossing. Transepts create across shape; the term cruciform (cross-like) basilica designates Early Christian churches with transepts. At St. Peter's, as in many Roman basilicas, wooden beams supported a gable roof, and clerestory windows allowed light to illuminate the nave. Many of the columns used in building Old St. Peter's were taken from earlier Roman buildings; materials thus reused are known as spolia (Latin, "spoils"). The group of spiral columns that decorated the altar area at Old St. Peter's had a special significance, for they were thought to have been taken from the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. The size of Old St. Peter's mirrors the triumphant attitude of Christianity following the Edict of Milan in 313, which granted religious freedom to the Christians. -

The Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan St Mary’s Byzantine Catholic Church Adult Education Series Ed. Deacon Mark Koscinski CPA D.Litt. The "Edict of Milan " (313 A. D.) The Edict of Milan was adopted by two of the three Roman Emperors shortly after the decisive Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312. Constantine the Great had defeated the usurper Maxentius, his brother-in-law, who controlled Italy and the Civil Diocese of Africa. Constantine fought under the standard of the Chi-Rho, and was victorious. In recognition for the help the Christian God had given him, and in order to keep the civil peace, Constantine and Licinius declared toleration for Christians throughout the Empire. This did not end persecution, as the third Emperor was a severe persecutor of Christians. Indeed, Licinius also later persecuted Christians as well. However, this truly was the beginning of the end of Christian persecution in the Empire. In 2013, Europe celebrated the Edict of Milan for its enlightened view of religious toleration. The Edict of Milan is often not recognized for what it was: a first step in true liberty. The contents of this Edict, with footnotes, follows. +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ When I, Constantine Augustus1, as well as I Licinius Augustus 2 fortunately met near Mediolanurn (Milan)3, and were considering everything that pertained to the public welfare and security, we thought , among other things which we saw would be for the good of many, those regulations pertaining to the reverence of the Divinity4 ought certainly to be made first, so that we might grant to the Christians and others full authority to observe that religion which each preferred5; whence any Divinity whatsoever in the seat of the heavens may be propitious and kindly disposed to us and all who are placed under our rule. -

Serdica Еdict (311 AD): Concepts and Realizations of the Idea of Religious Toleration the Book Is Published in 2014

SERDICa ЕdICT (311 AD): CONCEPTS AND REALIZATIONS OF THE IDEA OF RELIGIOUS TOLERATION The book is published in 2014. This is 1849 years after the beginning of Bulgarian statehood in Europe (165 AD) and 1333 years after the establishment of Danubian Bulgaria (681 AD) by Kan Asparuh. Bulgaria is the oldest European state existing under the same name for over eighteen centuries, and preserved by the Bulgarian nation to this day. Serdica Еdict (311 AD): CONCEPTS AND REALIZATIONS OF THE IDEA OF RELIGIOUS TOLERATION Proceedings of the international interdisciplinary conference “Serdica Edict (311 AD): Concepts and Realizations of the Idea of Religious Toleration”, Sofia, 2012 © TANGRA TanNakRa Publishing House Ltd, 2014 CENTRE FOR RESEARCH ON THE BULGARIANS © Edited by Vesselina Vachkova and Dimitar Dimitrov © Translator: Vanya Nikolova ISBN 978-954-378-102-7 All rights reserved. The publication of the book or parts of it in any form whatever, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, transcript or any other mode without the written publisher’s consent is forbidden. TANGRA TanNakRa Publishing House Ltd CENTRE FOR RESEARCH ON THE BULGARIANS Sofia, 2014 CONTENTS HAS THE EDICT OF SERDICA BEEN FORGOTTEN (some introductory words to this volume) – Vesselina Vachkova – Sofia, Bulgaria .................................7 WHY HAS THE EDICT OF AD 311 BEEN IGNORED? – Elizabeth DePalma Digeser – Santa Barbara, USA ................................................15 LEGAL ASPECTS OF THE SERDICA EDICT OF EMPEROR GALERIUS DD. 30 APRIL 311 AD. – Malina Novkirishka-Stoyanova -

Review Test Submission: Unit IV Assessment

2 Logout Home Notifications My Community HY 1010-17N-1, Western Civilization I Unit IV Review Test Submission: Unit IV Assessment Review Test Submission: Unit IV Assessment User Course HY 1010-17N-1, Western Civilization I Test Unit IV Assessment Started 5/4/19 2:12 PM Submitted 5/5/19 11:46 AM Status Completed Attempt Score 94 out of 100 points Time Elapsed 21 hours, 33 minutes Instructions Assessment Instructions Results Displayed Submitted Answers, Correct Answers, Feedback Question 1 2 out of 2 points Which of the following ideas did St. Augustine of Hippo NOT promote? Selected Answer: Christianity as the cause of the fall of Rome Correct Answer: Christianity as the cause of the fall of Rome Question 2 2 out of 2 points Which of the following is a factor that shaped medieval society? Selected Answer: Decreasing centralization of land ownership Correct Answer: Decreasing centralization of land ownership Question 3 2 out of 2 points Which of the following stories is apocryphal? Selected Answer: The Donation of Constantine Correct Answer: The Donation of Constantine Question 4 0 out of 2 points Which of the following is NOT included in Justinian's Code? Selected Answer: A summary of empire law identifying correct Christian belief Correct Answer: A summary of customary law related to taxation Question 5 2 out of 2 points Which of the following provides the correct chronological sequence of events? Selected Answer: The Visigoth defeat of Rome at the Battle of Adrianople, the Roman retreat from the British Isles, the Vandals capture of North Africa, the Hun attack on the Byzantine Empire, the Ostrogoth capture of Rome Correct Answer: The Visigoth defeat of Rome at the Battle of Adrianople, the Roman retreat from the British Isles, the Vandals capture of North Africa, the Hun attack on the Byzantine Empire, the Ostrogoth capture of Rome Question 6 0 out of 2 points Which of the following is an apocryphal story about St. -

EDICT of MILAN on the Way to the Great Jubilee in 2013

Conference EVERLASTING VALUE AND PERMANENT ACTUALITY OF THE EDICT OF MILAN On the Way to the Great Jubilee in 2013 Book 2 The Edict of Milan (313-2013): A Basis for Freedom of Religion or Belief? Belgrade, September 2013 Under the auspices of His Holiness Mr. Irinej, the Serbian Patriarch EVERLASTING VALUE AND PERMANENT ACTUALITY OF THE EDICT OF MILAN – ON THE WAY TO THE GREAT JUBILEE IN 2013 BOOK 2 – THE EDICT OF MILAN (313-2013): A BASIS FOR FREEDOM OF RELIGION OR BELIEF? Publisher Association of Nongovernmental Organizations of SEE – CIVIS Dobračina 15/VII, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia Tel: +381 11 26 21 723, Fax: +381 11 26 26 332 www.civis-see.org For the publisher Mirjana PRLJEVIĆ Chief Editor Mirjana PRLJEVIĆ Editor Marina ĐUROVIĆ Proofreading Language Shop Translators Aleksandar SEKULIĆ Bogdan LUBARDIĆ Dragoljub BOGOSAVLJEVIĆ Miloš RADIVOJEVIĆ Marina ĐUROVIĆ Essay about Roman Emperors prepared by: Mirjana PRLJEVIĆ Miloš RADIVOJEVIĆ Design & Prepress Marko ZAKOVSKI Printed by Graphic, Novi Sad Press run: 500 pcs ISBN: 978-86-911779-1-1 The publishing of this book was supported by: Swiss Peace and Crises Management Foundation www.fondmir.com We are very grateful for the wholehearted support and thoughtfulness during the realisation of our three year project “Everlasting Value and Permanent Actuality of the Edict Of Milan – On the Way to the Great Jubilee in 2013” to His Holiness Serbian Patriarch, Mr. Irinej His Grace Bishop Irinej of Bačka and Diocese of Bačka H.E. Mоns. Stanislav Hočevar Archbishop of Belgrade and Metropolitan H.E. Orlando Antonini Apostolic Nuncio of the Holy See in Serbia Mr. -

The Edict of Milan Through the Prism of Students at the Faculty of Orthodox Theology in Macedonia

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 34 Issue 1 Article 1 1-2014 The Edict of Milan through the Prism of Students at the Faculty of Orthodox Theology in Macedonia Ruzhica Cacanoska Methodius University Maja Angelovska Institute of National History Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Cacanoska, Ruzhica and Angelovska, Maja (2014) "The Edict of Milan through the Prism of Students at the Faculty of Orthodox Theology in Macedonia," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 34 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol34/iss1/1 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EDICT OF MILAN THROUGH THE PRISM OF STUDENTS AT THE FACULTY OF ORTHODOX THEOLOGY IN MACEDONIA1 By Ruzhica Cacanoska and Maja Angelovska Panova Prof. Ruzhica Cacanoska, PhD. (ruzica–[email protected]) , is research counselor at the Institute for Sociological, Political and Juridical Research in Skopje of Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, Republic of Macedonia. Among her publications are “Religion and Religious Customs in the Border Area – Case Study Koleshino,” “Religion and National Identity in Mono-Confessional and Multi-Confessional Countries in Europe and in the Balkans” (with co-author Nonka Bogomilova), and “Public Religion.” Prof.