Shattered Lives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ang Higante Sa Gubat

Isabela School of Arts and Trades, Ilagan Quirino Isabela College of Arts and Technology, Cauayan Cagayan Valley College of Quirino, Cabarroguis ISABELA COLLEGES, ▼ Cauayan Maddela Institute of Technology, Maddela ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, ▼ Angadanan Quirino Polytechnic College, Diffun ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, ▼Cabagan QUIRINO STATE COLLEGE ▼ Diffun, Quirino ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, Cauayan Polytechnic College, ▼Cauayan ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, ▼Echague Region III (Central Luzon ) ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, ▼Ilagan ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, ▼Jones ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, ▼Roxas Aurora ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, ▼San Mariano AURORA STATE COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY, ▼ Baler ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY, ▼San Mateo Mount Carmel College, Baler Mallig Plains College, Mallig Mount Carmel College of Casiguran, Casiguran Metropolitan College of Science and Technology, Santiago Wesleyan University Philippines – Aurora Northeast Luzon Adventist School of Technology, Alicia Northeastern College, Santiago City Our Lady of the Pillar College of Cauayan, Inc., Cauayan Bataan Patria Sable Corpus College, Santiago City AMA Computer Learning Center, Balanga Philippine Normal University, Alicia Asian Pacific College of Advanced Studies, Inc., Balanga Southern Isabela College of Arts and Trade, Santiago City Bataan (Community) College, Bataan Central Colleges, Orani S ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY ▼ Echague, Isabela Bataan Heroes Memorial College, Balanga City Saint Ferdinand College-Cabagan, Cabagan BATAAN POLYTECHNIC STATE COLLEGE, ▼Balanga City Saint Ferdinand -

Lanao Del Norte – Homosexual – Dimaporo Family – Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF)

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: PHL33460 Country: Philippines Date: 2 July 2008 Keywords: Philippines – Manila – Lanao Del Norte – Homosexual – Dimaporo family – Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide references to any recent, reliable overviews on the treatment of homosexual men in the Philippines, in particular Manila. 2. Do any reports mention the situation for homosexual men in Lanao del Norte? 3. Are there any reports or references to the treatment of homosexual Muslim men in the Philippines (Lanao del Norte or Manila, in particular)? 4. Do any reports refer to Maranao attitudes to homosexuals? 5. The Dimaporo family have a profile as Muslims and community leaders, particularly in Mindanao. Do reports suggest that the family’s profile places expectations on all family members? 6. Are there public references to the Dimaporo’s having a political, property or other profile in Manila? 7. Is the Dimaporo family known to harm political opponents in areas outside Mindanao? 8. Do the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) recruit actively in and around Iligan City and/or Manila? Is there any information regarding their attitudes to homosexuals? 9. -

PHILIPPINES Manila GLT Site Profile

PHILIPPINES Manila GLT Site Profile AZUSA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY GLOBAL LEARNING TERM 626.857.2753 | www.apu.edu/glt 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO MANILA ................................................... 3 GENERAL INFORMATION ........................................................ 5 CLIMATE AND GEOGRAPHY .................................................... 5 DIET ............................................................................................ 5 MONEY ........................................................................................ 6 TRANSPORTATION ................................................................... 7 GETTING THERE ....................................................................... 7 VISA ............................................................................................. 8 IMMUNIZATIONS ...................................................................... 9 LANGUAGE LEARNING ............................................................. 9 HOST FAMILY .......................................................................... 10 EXCURSIONS ............................................................................ 10 VISITORS .................................................................................. 10 ACCOMODATIONS ................................................................... 11 SITE FACILITATOR- GLT PHILIPPINES ................................ 11 RESOURCES ............................................................................... 13 NOTE: Information is subject to -

Pdf | 474.14 Kb

PHILIPPINES - Mindanao: 3W - Who does, What, Where (comPhilippines:pleted, ongoing, Central planned Mindanao activities) Who-does as of 31 WhatMarch Where2015 (3W) as of December 2013 124°0'0"E 124°15'0"E 124°30'0"E 124°45'0"E Shoreline Regional boundary TALITAY DATU PIANG DATU SALIBO SHARIFF SAYDONA MUSTAPHA Provincial boundary FAO/DA‐ Sultan KudaratFSD/PCBL IOM/DSWD‐ARMM Municipal boundary Maguindanao, DAF‐ IOM/DSWD‐ARMM; Primary road ARMM, BFAR‐ARMM PLAN Int/MTB PLGU‐Maguindanao; Affected municipalities & MMI Bangsamoro Development Number of displaced people PLGU‐Maguindanao; Agency; FAO/DA‐ UNFPA/DOH‐ARMM Kadtuntaya Maguindanao, DAF‐ 0 - 750 DATU ANGGAL MIDTIMBANG HOM/UNICEF Northern KabuntalanFoundation, Inc.; ARMM, BFAR‐ARMM & FSD/PCBL 751 - 3,100 FSD/PCBL FAO/DA‐ MMI FAO/DA‐Maguindanao, KFI/CRS; UNICEF/ Maguindanao, DAF‐ DAF‐ARMM, BFAR‐ MTB/MERN 3101 - 6,200 ASDSW ARMM, BFAR‐ARMM ARMM & MMI & MMI FSD/PCBL; Save the MTB/MERN Children/MERN 6,201 - 13,500 ´ UNFPA/DOH‐ARMM Save the Children/MERN Kabuntalan FSD/PCBL; Save the RAJAH BUAYAN KFI/CRS NorthNorth CotabatoCotabatoMOSEP/UNFPA, CHT; Datu Montawal more than 13,500 Children/MERN PLGU‐Maguindanao; UNFPA/DOH‐ARMM MTB; FAO/DA‐ Datu Odin Sinsuat Save the Affected municipalities GUINDULUNGAN ASDSW/UNICEF; Save the Maguindanao, DAF‐ Children/MERN Marshland IOM/DSWD‐ARMM; Children ARMM, BFAR‐ARMM KFI/CRS Save the & MMI FAO/DA‐ Children/MERN; HOM/UNICEF Maguindanao, DAF‐ MTB/PLAN Int. UNHCR/MDRRMO/B ARMM, BFAR‐ARMM LGU; FSD/PCBL Cluster & MMI ! Talitay ! Food and Agriculture MTB/MERN Datu HealthBlah incl. RHT. and Sinsuat MHPSS UNFPA/DOH‐ARMM Datu Salibo ! Protection incl. -

Women's Involvement in Conflict Early Warning Systems

October 2012 OPINION Women’s involvement in conflict early warning systems: Moving from rhetoric to reality in Mindanao Mary Ann M. Arnado The views expressed in this opinion are those of its author, and not necessarily the views of the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue. The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue community. We deploy our expertise This Opinion is produced as part of the (the HD Centre) is an independent to support local and nationally-owned HD Centre’s project, ‘Women at the organisation dedicated to improving the processes that protect civilians and Peace Table - Asia Pacific’, which brings prevention of, and response to, armed foster lasting and just peace. together women active in peacemaking conflict. The HD Centre opens channels For more information, please visit: accross the Asia-Pacific region to of communication and mediates http://www.hdcentre.org identify and employ strategies for between parties in conflict, facilitates improving the contributions of women dialogue, and provides support to the to, and participation in, peace processes. broader mediation and peacebuilding Opinion “Today, our civil society counterpart is launching an all-women peace-keeping force, most likely the first we ever had in our history of waging peace in the country. I have always been optimistic that gradually and one day, we would live to see ourselves go beyond the rhetoric and witness women really move to the front and centre of the peace process.” Teresita Quintos-Deles, Philippines Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process, October 5, 20101 Introduction United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000), hereafter referred to as 1325, calls upon United Nations (UN) Member States to recognise and promote the participation of women in peace and security processes. -

Chapter 3 Socio Economic Profile of the Study Area

CHAPTER 3 SOCIO ECONOMIC PROFILE OF THE STUDY AREA 3.1 SOCIAL CONDITIONS 3.1.1 Demographic Trend 1) Population Trends by Region Philippine population has been continuously increasing from 48.1million in 1980, 76.3 million in 2000 to 88.5million in 2007 with 2.15% of annual growth rate (2000-2007). Population of both Mindanao and ARMM also showed higher increases than national trend since 2000, from 18.1 in 2000 to 21.6 million in 2007 (AAGR: 2.52%), and 2.9 in 2000 to 4.1million in 2007 (AAGR: 5.27%), respectively. Population share of Mindanao to Philippines and of ARMM to Mindanao significantly increased from 23.8% to 24.4% and 15.9% to 24.4%, respectively. 100,000,000 90,000,000 Philippines Mindanao 80,000,000 ARMM 70,000,000 60,000,000 50,000,000 40,000,000 30,000,000 20,000,000 10,000,000 0 1980 1990 1995 2000 2007 Year Source: NSO, 2008 FIGURE 3.1.1-1 POPULATION TRENDS OF PHILIPPINES, MINDANAO AND ARMM Population trends of Mindanao by region are illustrated in Figure 3.1.1-2 and the growth in ARMM is significantly high in comparison with other regions since 1995, especially from 2000 to 2007. 3 - 1 4,500,000 IX 4,000,000 X XI 3,500,000 XII XIII ARMM 3,000,000 2,500,000 2,000,000 1,500,000 1,000,000 1980 1990 1995 2000 2007 year Source NSO, 2008 FIGURE 3.1.1-2 POPULATION TRENDS BY REGION IN MINDANAO As a result, the population composition within Mindanao indicates some different features from previous decade that ARMM occupies a certain amount of share (20%), almost same as Region XI in 2007. -

Counter-Insurgency Vs. Counter-Terrorism in Mindanao

THE PHILIPPINES: COUNTER-INSURGENCY VS. COUNTER-TERRORISM IN MINDANAO Asia Report N°152 – 14 May 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. ISLANDS, FACTIONS AND ALLIANCES ................................................................ 3 III. AHJAG: A MECHANISM THAT WORKED .......................................................... 10 IV. BALIKATAN AND OPLAN ULTIMATUM............................................................. 12 A. EARLY SUCCESSES..............................................................................................................12 B. BREAKDOWN ......................................................................................................................14 C. THE APRIL WAR .................................................................................................................15 V. COLLUSION AND COOPERATION ....................................................................... 16 A. THE AL-BARKA INCIDENT: JUNE 2007................................................................................17 B. THE IPIL INCIDENT: FEBRUARY 2008 ..................................................................................18 C. THE MANY DEATHS OF DULMATIN......................................................................................18 D. THE GEOGRAPHICAL REACH OF TERRORISM IN MINDANAO ................................................19 -

74C312c0efe4410d49257659

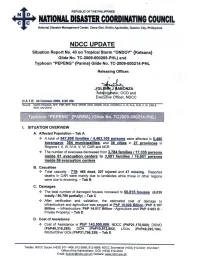

5 NDCC Rice assistance – 23,200 sacks of rice were already distributed to the LGUs in Regions I (9,500), II (2,400), III (2,300), IV-A (1,000), IV-B (1,000), V (3,000), CAR (3,100) and NCR (900) 5 Based on the Financial Tracking System (FTS), the Philippine Flash Appeal of 74M USD have received from donors 20.2M USD with 27.3% coverage E. Status of Roads and Bridges – Tab F 5 As per report of DPWH, 11 road sections and 4 bridges are still impassable as of October 23, 2009 due to series of slides, scoured and washed out bridge approach, road cuts and scoured slopes protection Damaged Road Sections (5 in CAR and 7 in Region I) and damaged bridges are Salacop Bridge in Benguet; San Vicente Bridge in La Union, Bued Bridge and Carayungan Bridge in Pangasinan II. HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE A. Food and NFIs 5 DSWD provided PhP40.15 Million worth of relief augmentation support/ assistance consisting of food (rice, canned goods, biscuits) and non food items (mats, blankets and clothing) to DSWD Field Offices and processing release of PhP15.5 M as additional stand-by funds for the purchase of relief commodities and other purposes for the on-going disaster operations: DSWD CAR (PhP 2M), I (PhP 3M), II (PhP 2M), III (PhP 5M), IV-A (PhP 2M), IV-B (PhP 0.5M) and V (PhP 1M) 5 Air logistics support for the transport of food and NFIs to Regions II and CAR was provided by the PAF–AFP and UNHAS helicopter sorties of UN-WFP 5 Unserved families in the inaccessible areas in the Islands of Calayan and Fuga, Aparri, Cagayan and Kibungan and Mankayan, Benguet were served through airlift operations B. -

Volume Xxiii

ANTHROPOLOGICAL PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY VOLUME XXIII NEW YORK PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES 1925 Editor CLARK WISSLER FOREWORD Louis ROBERT SULLIVAN Since this volume is largely the work of the late Louis Robert Sulli- van, a biographical sketch of this able anthropologist, will seem a fitting foreword. Louis Robert Sullivan was born at Houlton, Maine, May 21, 1892. He was educated in the public schools of Houlton and was graduated from Bates College, Lewiston, Maine, in 1914. During the following academic year he taught in a high school and on November 24, 1915, he married Bessie Pearl Pathers of Lewiston, Maine. He entered Brown University as a graduate student and was assistant in zoology under Professor H. E. Walters, and in 1916 received the degree of master of arts. From Brown University Mr. Sullivan came to the American Mu- seum of Natural History, as assistant in physical anthropology, and during the first years of his connection with the Museum he laid the foundations for his future work in human biology, by training in general anatomy with Doctor William K. Gregory and Professor George S. Huntington and in general anthropology with Professor Franz Boas. From the very beginning, he showed an aptitude for research and he had not been long at the Museum ere he had published several important papers. These activities were interrupted by our entrance into the World War. Mr. Sullivan was appointed a First Lieutenant in the Section of Anthropology, Surgeon-General's Office in 1918, and while on duty at headquarters asisted in the compilation of the reports on Defects found in Drafted Men and Army Anthropology. -

The Ideology of the Dual City: the Modernist Ethic in the Corporate Development of Makati City, Metro Manila

bs_bs_banner Volume 37.1 January 2013 165–85 International Journal of Urban and Regional Research DOI:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01100.x The Ideology of the Dual City: The Modernist Ethic in the Corporate Development of Makati City, Metro Manila MARCO GARRIDO Abstractijur_1100 165..185 Postcolonial cities are dual cities not just because of global market forces, but also because of ideological currents operating through local real-estate markets — currents inculcated during the colonial period and adapted to the postcolonial one. Following Abidin Kusno, we may speak of the ideological continuity behind globalization in the continuing hold of a modernist ethic, not only on the imagination of planners and builders but on the preferences of elite consumers for exclusive spaces. Most of the scholarly work considering the spatial impact of corporate-led urban development has situated the phenomenon in the ‘global’ era — to the extent that the spatial patterns resulting from such development appear wholly the outcome of contemporary globalization. The case of Makati City belies this periodization. By examining the development of a corporate master-planned new city in the 1950s rather than the 1990s, we can achieve a better appreciation of the influence of an enduring ideology — a modernist ethic — in shaping the duality of Makati. The most obvious thing in some parts of Greater Manila is that the city is Little America, New York, especially so in the new exurbia of Makati where handsome high-rise buildings, supermarkets, apartment-hotels and shopping centers flourish in a setting that could well be Palm Beach or Beverly Hills. -

Pdf | 271.85 Kb

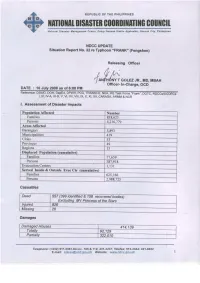

Estimated Cost of Damages Php13,320,954 M (Php13.321 Billion) Agriculture (Production loss) Php 7,541.777 M Crops 1,400.783 M HVCC 475.831 M Livestock 93.777 M Fisheries 2,654..425 M Facilities 2,916.951 M Infrastructure Php5,779.178 M Roads, Bridges and Others Structures 4,239.486 M School Buildings /Classrooms 888.901 M Electrical Facilities 297.900 M Health Facilities and Others 352.891 M II. Humanitarian Assistance The extent of assistance provided by the Government is Php 125.187 Million Agencies Assistance Cost (Millions) OCD- NDCC 18,390 sacks of rice P16.781 National Agencies DSWD Assorted food packs , NFIs 37.508 DOH Drugs, medicines, medical 16.285 supplies , compact food Dep Ed Clearing and immediate repair 30.000 of sch buildings in Region VI LGUs Assorted food and NFIs 24.613 Total Php125.187 International Donations (Foreign Governments and INGOs) - Cash and Checks - US$613,074.00 and Aus $500,000.00 - In Kind - P22,300,000.00 and US$650,000,000.00 Donors Recipients Cash (Checks) In Kind USAID PNRC US $100,000.00 US $ 650,000.00 worth of relief supplies French PNRC US$110,000.00 AUSAID PNRC Aus$ 500,000.00 Spain PNRC Php6,300,000.00 (assorted relief goods & equipment Korea NDCC US$ 300,000.00 Other INGOs NDCC US$ 3,074.00 China NDCC US$100,000.00 (Check) JICA DSWD Phh16,000,000.00 worth (20 gen sets, 150 pcs plastic sheets, 600 pcs sleeping pads, 10 units water tanks and 20 cord reel; 200 boxes (6 pcs /box) sleeping mattress, 180 pieces plastic rolls, 100 boxes (12 pcs/box) polyester tank 2 Local Assistance /Donations -

Violence As a Means of Control and Domination in the Southern Philippines: How Violence Is Used to Consolidate Power in the Southern Phillipines Kreuzer, Peter

www.ssoar.info Violence as a means of control and domination in the Southern Philippines: how violence is used to consolidate power in the Southern Phillipines Kreuzer, Peter Arbeitspapier / working paper Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: Hessische Stiftung Friedens- und Konfliktforschung (HSFK) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kreuzer, P. (2011). Violence as a means of control and domination in the Southern Philippines: how violence is used to consolidate power in the Southern Phillipines. (PRIF Reports, 105). Frankfurt am Main: Hessische Stiftung Friedens- und Konfliktforschung. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-321657 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public.