Ottawa September 2011 'To Render War Impossible'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report FY17-18

2017/18 The Rhodes Trust Second Century Annual Report 2017/18 Trustees 2017/18 Sir John Hood KNZM, Chairman Professor Margaret Professor Ngaire Woods CBE (New Zealand & Worcester 1976) MacMillan CH, CC (New Zealand & Balliol 1987) Andrew Banks Dr Tariro Makadzange John Wylie AM (Florida & St Edmund Hall 1976) (Zimbabwe & Balliol 1999) (Queensland & Balliol 1983) Dominic Barton Michael McCaffery (British Columbia & Brasenose 1984) (Pennsylvania & Merton 1975) New Trustees 2018 Professor Sir John Bell GBE John McCall MacBain O.C. Robert Sternfels (Alberta & Magdalen 1975) (Québec & Wadham 1980) (California & Worcester 1992) Professor Elleke Boehmer Nicholas Oppenheimer Katherine O’Regan (South Africa-at-Large and St John’s 1985) Professor Dame Carol Robinson DBE Dame Helen Ghosh DCB Trustee Emeritus Dilip Shangvhi Donald J. Gogel Julian Ogilvie Thompson (New Jersey & Balliol 1971) Peter Stamos (Diocesan College, Rondebosch (California & Worcester 1981) & Worcester 1953) Glen James Judge Karen Stevenson (Maryland/DC & Magdalen 1979) Development Committee Andrew Banks, Chairman Bruns Grayson The Hon. Thomas McMillen (Florida & St Edmund Hall 1976) (California & University 1974) (Maryland & University 1974) Nicholas Allard Patrick Haden Timothy Orton (New York & Merton 1974) (California & Worcester 1975) (Australia-at-Large & Magdalen 1986) Dominic Barton Sir John Hood KNZM Lief Rosenblatt (British Columbia & Brasenose 1984) (New Zealand & Worcester 1976) (Massachusetts & Magdalen 1974) Shona L. Brown Sean Mahoney Arthur Scace, CM, QC, LLD (Ontario & New College 1987) (Illinois & New College 1984) (Ontario & Corpus Christi 1961) Gerald J. Cardinale Jacko Maree The Hon. Malcolm Turnbull MP (Pennsylvania & Christ Church 1989) (St Andrews College, Grahamstown (New South Wales & Brasenose 1978) & Pembroke 1978) Sir Roderick Eddington Michele Warman (Western Australia & Lincoln 1974) Michael McCaffery (New York & Magdalen 1982) (Pennsylvania & Merton 1975) Michael Fitzpatrick Charles Conn (Western Australia & St Johns 1975) John McCall MacBain O.C. -

In This Issue

Summer 2018 VOLUME 20, NUMBER 1 IN THIS ISSUE: What Is CUAC, Anyway? Our New Steering Committee Advises on Fundraising India Chapter Discusses ‘Saffronization’ CUAC Member News CUAC will be at The 79th General Convention of The Episcopal Church Service Learning in Asia Nineteen-year-old broadcasting student Kent Andres works with Filipino children at Trinity University of Asia in Quezon City, Philippines, in this year’s CUAC Service Learning Pro- July 5-13, 2018 gram. Austin, Texas Please See Story, Page Seven CUAC Compass Points Summer 2018 What Is CUAC? CUAC is an idea …namely, that in a troubled world filled with conflict, there are still ways to bring people together in pursuit of a shared ideal. CUAC is a reality …embodied in a global network linking 160 colleges and universities in six continents, institutions large and small, old and new, all sharing a common heritage of faith-inflected, value-rooted education. CUAC is an NGO for the soul …other Non-Governmental Organizations deal with development issues or social and medical challenges. CUAC is among the few that see that nurturing the souls of young people through transformational teaching is as important as healing the body. CUAC is an experiment in ‘applied genealogy’ …because we celebrate and keep alive the shared heritage of institutions that honor their historic Anglican and Episcopalian roots. CUAC is ‘a wildly diverse group of people’ …as only an organization can be that brings together teachers, staff, and students from South Asia, East Asia, Oceana, Africa, Europe, North American, South America in a far-ranging conversation always respectful of cultural differences. -

Information for Candidates for The

USA THE RHODES SCHOLARSHIP FOR UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Covering the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and U.S. territories INFORMATION FOR CANDIDATES - for selection for 2022 only (This Memorandum cancels those issued for previous years) Background Information The Rhodes Scholarships, established in 1903, are the oldest international scholarship programme in the world, and one of the most prestigious. Administered by the Rhodes Trust in Oxford, the programme offers 100 fully-funded Scholarships each year for postgraduate study at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom - one of the world’s leading universities. Rhodes Scholarships are for young leaders of outstanding intellect and character who are motivated to engage with global challenges, committed to the service of others and show promise of becoming value-driven, principled leaders for the world’s future. The broad selection criteria are: Academic excellence – specific academic requirements can be found under ‘Eligibility Criteria’ below. Energy to use your talents to the full (as demonstrated by mastery in areas such as sports, music, debate, dance, theatre, and artistic pursuits, including where teamwork is involved). Truth, courage, devotion to duty, sympathy for and protection of the weak, kindliness, unselfishness and fellowship. Moral force of character and instincts to lead, and to take an interest in your fellow human beings. Please see the Scholarships area of the Rhodes Trust website for full details: www.rhodeshouse.ox.ac.uk Given the current situation with the Covid-19 pandemic, aspects of the application requirements and subsequent selection processes may be subject to change. Our website and this document will be updated with any changes, and once you have started an application any changes will be communicated via email. -

Mathematics People

Mathematics People Mathematics Student Wins physicists might apply to help understand the fundamen- tal forces of nature: electricity, magnetism, and gravity. Siemens Competition “Mr. Vaintrob found a very beautiful formula for de- scribing the way shapes combine in string theory,” said For the second straight year, a high school mathematician competition judge Michael Hopkins of Harvard Universi- has won the grand prize in the Siemens Competition in ty. “His work is at the Ph.D. level, publishable and already Math, Science, and Technology. The top honors for the attracting the attention of researchers.” 2006–2007 competition went to Dmitry Vaintrob, a Vaintrob was introduced to this topic of research by senior at South Eugene High School in Eugene, Oregon. He his mentor, Pavel Etingof of the Massachusetts Institute won a US$100,000 scholarship in the individual category. of Technology, who proposed a problem that came out of Vaintrob’s project, “The String Topology BV Algebra, his own recent work. “It was an insanely difficult problem, Hochschild Cohomology, and the Goldman Bracket on Sur- which he solved within weeks and then came up with an faces”, involves the new mathematical field of string topol- important additional development,” said Hopkins. “This ogy. Focusing on mathematical shapes, his work offers in- brilliant young mathematician showed amazing maturity sights that are universal and applicable in any field. His re- and perspective which would be surprising in a graduate search could provide knowledge that mathematicians and student, let alone a high school senior.” Vaintrob is a volunteer in his high school library and in themathematicslibraryattheUniversityofOregon.Healso organized the math club in his high school. -

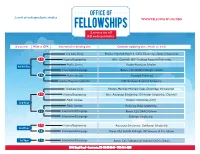

Fellowships Flowchart FA17

A unit of undergraduate studies WWW.FELLOWSHIPS.KU.EDU A service for all KU undergraduates If you are: With a GPA: Interested in funding for: Consider applying for: (details on back) Graduate Study Rhodes, Marshall, Mitchell, Gates-Cambridge, Soros, Schwarzman 3.7+ Science/Engineering Also: Churchill, NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Public Service Knight-Hennessy Scholars 4th/5th Year International/Language Boren, CLS, DAAD, Fulbright, Gilman 3.2+ Public Service Carnegie, Pickering Science/Engineering/SocSci NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Graduate Study Rhodes, Marshall, Mitchell, Gates-Cambridge, Schwarzman 3.7+ Science/Engineering Also: Astronaut Scholarship, Goldwater Scholarship, Churchill Public Service Truman Scholarship (3.5+) 3rd Year Public Service Pickering, Udall Scholarship 3.2+ International/Language Boren, CLS, DAAD, Gilman International/Language Fulbright Scholarship 3.7+ Science/Engineering Astronaut Scholarship, Goldwater Scholarship 2nd Year 3.2+ International/Language Boren, CLS, DAAD, Fulbright UK Summer, (3.5+), Gilman 1st Year 3.2+ International/Language Boren, CLS, Fulbright UK Summer, (3.5+), Gilman 1506 Engel Road • Lawrence, KS 66045-3845 • 785-864-4225 KU National Fellowship Advisors ✪ Michele Arellano Office of Study Abroad WE GUIDE STUDENTS through the process of applying for nationally and internationally Boren and Gilman competitve fellowships and scholarships. Starting with information sessions, workshops and early drafts [email protected] of essays, through application submission and interview preparation, we are here to help you succeed. ❖ Rachel Johnson Office of International Programs Fulbright Programs WWW.FELLOWSHIPS.KU.EDU [email protected] Knight-Hennessy Scholars: Full funding for graduate study at Stanford University. ★ Anne Wallen Office of Fellowships Applicants should demonstrate leadership, civic commitment, and want to join a Campus coordinator for ★ awards. -

Indigenous Leadership

WINTER 2011 ContactFOR ALUMNI & COMMUNITY In this issue: n Flood recovery in focus n Colleges mark centenaries n Antiquities rehoused n Honouring our donors Indigenous leadership UQ APPOINTS NEW PRO VICE-CHANCELLOR UQ research students are discovering Consistently ranked in the top 1% of all innovativeinnovative solutionssolutions toto some of the world’s universities in the world, UQ plays a leading most challenging questions. Supported by role in research collaboration and innovation. over 2000 experts across a wide range of The 2010 Excellence in Research for disciplines, UQ offers a focused environment Australia assessment confirmed UQ as having forfor itsits studentsstudents to excel. more researchers working in fields assessed Every research student benefits from UQ’s above world standard than at any other acclaimed culture of research excellence, Australian university. acclaimed culture of research excellence, Australian university. uq.edu.au/grad-school which includes world-renowned advisors, Whatever you want to achieve, however extensive international networks and ongoing you want to succeed, you will enjoy every professional development opportunities. advantage at The University of Queensland. The University of You. UOQ 0957 Research Grad Ad_297x210.indd 1 24/05/11 4:18 PM UOQ 0957 Research Grad Ad_297x210.indd 1 24/05/11 4:18 PM From the Chancellor CONTENTS 06 12 Welcome to the Winter 2011 edition of Contact magazine. The academic year started in an unforgettable fashion, with devastating floods inundating large parts of Queensland, including the St Lucia and Gatton campuses. On pages 14–15 you’ll find related stories and a gallery of striking photographs that help capture the historic event from the University’s perspective. -

DRAFT 2020 Document Coming Soon

CHINA THE RHODES SCHOLARSHIP FOR CHINA - IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE OXFORD-SCHWARZMAN-CHINA GRADUATE SCHOLARSHIP INFORMATION FOR CANDIDATES - for selection for 2019 only (This Memorandum cancels those issued for previous years) Background Information 2020The Rhodes Scholarship programme is the oldest (established 1903), and perhaps the most prestigious, international scholarship programme in the world. Administered by the Rhodes Trust in Oxford, the programme offers more than 100 fully-funded Scholarships each year for postgraduate study at the University of Oxford in the UK - one of the world’s leading universities. Selection Committees for the Scholarships are looking for young leaders of outstanding intellect and character who are motivated to engage with global challenges, committed to the service of others and show promise of becoming value-driven, principled leaders for the world’s future. The Selection Committees are looking for the following: • academic excellence (e.g. First Class Honours or GPA of minimum 3.7 out of 4.0, or equivalent). Further details on the academic requirementsDocument can be found under ‘Eligibility Criteria’ below • energy to use your talents to the full (as demonstrated by mastery in areas such as sports, music, debate, dance, theatre, and artistic pursuits, particularly where teamwork is involved) • truth, courage, devotion to duty, sympathy for and protection of the weak, kindliness, unselfishness and fellowship • moral force of character and instincts to lead,DRAFT and to take an interest in your fellow human beings. Please see the Scholarships area of the Rhodes Trust website for full details: www.rhodeshouse.ox.ac.uk The information below assumes that you have read and familiarised yourself with the basic selection criteria for the Rhodes Scholarships on the Rhodes Trust website. -

ORGANIZATION DESCRIPTION Schwarzman Scholars Was Inspired by the Rhodes Scholarship, Which Was Founded in 1902 to Promote Intern

ORGANIZATION DESCRIPTION Schwarzman Scholars was inspired by the Rhodes Scholarship, which was founded in 1902 to promote international understanding and peace, and is designed to meet the challenges of the 21st century and beyond. Blackstone Co-Founder Stephen A. Schwarzman personally contributed $100 million to the program and is leading a fundraising campaign to raise an additional $500 million from private sources to endow the program in perpetuity. The $600 million endowment will support up to 200 scholars annually from the U.S., China and around the world for a one- year Master’s Degree program at Tsinghua University in Beijing, one of China’s most prestigious universities, ranked first in Asia, and an indispensable base for the country’s political, business, and technological leadership. Scholars chosen for this highly selective program will live in Beijing for a year of study and cultural immersion, attending lectures, and traveling and developing a better understanding of China. Admissions opened in the fall of 2015 with outstanding success, immediately making Schwarzman Scholars one of the world’s most selective graduate and fellowship programs. The first class of students took residence in the summer of 2016. Learn more about Schwarzman Scholars at www.schwarzmanscholars.org. The Stephen A. Schwarzman Education Foundation is a lean organization with a dedicated team working to drive the program’s mission forward. POSITION DESCRIPTION: DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Schwarzman Scholars seeks a Director of Marketing and Communications. This individual will help craft and execute marketing and communications strategies for the organization globally and oversee internal and external communications. -

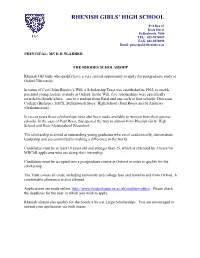

Message Cover Sheet

RHENISH GIRLS’ HIGH SCHOOL P O Box 87 Koch Street Stellenbosch, 7600 TEL: 021-8876807 FAX: 021-8878090 Email: [email protected] PRINCIPAL: MS E H SLABBER THE RHODES SCHOLARSHIP Rhenish Old Girls who qualify have a very special opportunity to apply for postgraduate study at Oxford University. In terms of Cecil John Rhodes’s Will, a Scholarship Trust was established in 1902, to enable potential young leaders to study at Oxford. In the Will, five scholarships were specifically awarded to South Africa – one to a student from Natal and one each to four schools: Diocesan College (Bishops), SACS, Stellenbosch Boys’ High School (Paul Roos) and St Andrews (Grahamstown). In recent years these scholarships have also been made available to women from their partner schools. In the case of Paul Roos, this opened the way to alumni from Rhenish Girls’ High School and Hoër Meisiesskool Bloemhof. The scholarship is aimed at outstanding young graduates who excel academically, demonstrate leadership and are committed to making a difference in the world. Candidates must be at least 19 years old and younger than 25, which is extended by 3 years for MBChB applicants who are doing their internship. Candidates must be accepted into a postgraduate course at Oxford in order to qualify for the scholarship. The Trust covers all costs, including university and college fees and travel to and from Oxford. A comfortable allowance is also allowed. Applications are made online: http://www.rhodeshouse.ox.ac.uk/southern-africa. Please check the deadlines for the year in which you wish to apply. -

Marshall/Mitchell/Rhodes (US & Canadian) Scholarships 2017-2018 Yale Notes for Writers of Letters of Reference

Marshall/Mitchell/Rhodes (US & Canadian) Scholarships 2017-2018 Yale notes for writers of letters of reference Letters of reference are an essential piece of an application for the Marshall, Mitchell, and Rhodes, as of so many other applications. Thank you for taking the time to advise this applicant, and perhaps to write a letter! When to say no: Scholarships such as the Marshall, Mitchell, and Rhodes are extremely competitive, and letters of recommendation play an important role in a student’s application. If you feel that for any reason you cannot write a strongly supportive recommendation for the student, please decline to write a letter at all. If you do not know the student well enough to write a detailed letter, or if you simply do not have the time to write a strong 1½-2-page letter, please decline. Applicants asking you for a letter should have done so in timely and helpful fashion. They should give you information about the scholarship(s) for which they are applying. They should also have outlined, and preferably discussed with you, why they are applying for the scholarship, what they’re hoping to do with it, and how they might be thinking of your letter in the context of the rest of the application. Should you wish, they may share with you copies of their personal statements [although see the note below], proposals of study, and/or information about extracurricular activities. If you have not been given adequate time or information to write a strong letter, you may wish to decline to write and would be well within your rights to do so. -

Affective Politics and Colonial Heritage, Rhodes Must Fall at UCT and Oxford

Affective Politics and Colonial Heritage, Rhodes Must Fall at UCT and Oxford By: Britta Timm Knudsen (Aarhus University) Casper Andersen (Aarhus University) INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HERITAGE STUDIES 2019, VOL. 25, NO. 3, 239 –258 https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2018.1481134 Affective politics and colonial heritage, Rhodes Must Fall at UCT and Oxford Britta Timm Knudsen a and Casper Andersen b aSchool of Culture and Communication, ARTS, Aarhus University, Denmark; bSchool of Culture and Society, ARTS, Aarhus University, Denmark ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The article analyses the spatial entanglement of colonial heritage strug- Received 29 September 2017 gles through a study of the Rhodes Must Fall student movement at the Accepted 17 May 2018 University of Cape Town and the University of Oxford. We aim to shed KEYWORDS light over why statues still matter in analyzing colonial traces and Colonial heritage; social legacies in urban spaces a nd how the decolonizing activism of the RMF movements; social media; movement mobilizes around the controversial heritage associated with affective politics; Cecil Rhodes at both places – a heritage that encompasses statues, decolonization buildings, Rhodes scholarship and the Rhodes Trust funds. We include a comparative study of the Facebook use of RM F as it demonstrates signi ficant di fferences between the two places in the development of the student movements as political activism. Investigating in more detail the heritage politics of RMF at UCT we fledge out what we call an affective politics using non-representational bodily strategies. We argue that in order for actual social movements to mobilize in current political controversies, they need to put a ffective tactics to use. -

Fellowships Flowchart.Pub (Read-Only)

*College nominaon/ If you are: With a GPA: Interested in funding for: You should consider: (details on back) endorsement required Graduate Study Rhodes*, Marshall*, Mitchell*, Gates‐Cambridge 3.7+ Science / Engineering Churchill*, NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Internaonal / Language Boren, DAAD*, Fulbright*, Gilman*, Luce* Senior Public Service Pickering 3.2+ Science / Engineering / Social Science NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Hampden‐Sydney College Humanies Lilly*, JKC Graduate Arts Award Office of Fellowship Advising Graduate Study Rhodes*, Marshall*, Mitchell*, Gates‐Cambridge Science / Engineering Goldwater*, Churchill* 3.7+ Public Service Truman (3.6+)* Junior Public Service Pickering, Udall* 3.2+ Internaonal / Language Boren*, DAAD*, Gilman* Science Goldwater* 3.7+ Sophomore Internaonal / Language Boren*, DAAD*, Fulbright UK Summer (3.5+), Gilman* 3.2+ Internaonal / Language Boren*, Fulbright UK Summer (3.5), Gilman* Freshman 3.2+ Adapted from Notre Dame University Nationally Competitive Scholarships Boren Fellowship and Scholarship: Summer, semester, and year-long study in regions critical to U.S. national security. Requires 1- year commitment to federal government. Churchill Scholarship: One year of graduate study in STEM at Cambridge University. DAAD Scholarships: Semester and yearlong internships/research/study in all fields in Germany. Deadlines vary. Some require college endorsement. Fulbright Grant: Cultural exchange funded by U.S. State Department. One year post-graduate fellowship for research, study, or teaching English abroad. Fulbright UK Summer Institutes: Three, four, or five week academic and cultural summer programs for freshmen and sophomores. Gates-Cambridge Scholarship: Post-graduate study at Cambridge University in all fields. Applicants must show evidence of commitment to improving the lives of others. Gilman Scholarship: Funding for study abroad to non-traditional areas for students receiving Pell Grants.