The Four Main Primate Movement Patterns • How Primates’ Bodies and Movement Are Related to Their Habitat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

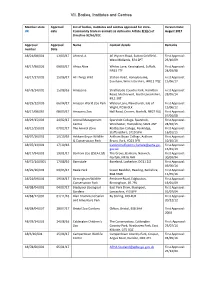

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

Verzeichnis Der Europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- Und Tierschutzorganisationen

uantum Q Verzeichnis 2021 Verzeichnis der europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- und Tierschutzorganisationen Directory of European zoos and conservation orientated organisations ISBN: 978-3-86523-283-0 in Zusammenarbeit mit: Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. Deutsche Tierpark-Gesellschaft e.V. Deutscher Wildgehege-Verband e.V. zooschweiz zoosuisse Schüling Verlag Falkenhorst 2 – 48155 Münster – Germany [email protected] www.tiergarten.com/quantum 1 DAN-INJECT Smith GmbH Special Vet. Instruments · Spezial Vet. Geräte Celler Str. 2 · 29664 Walsrode Telefon: 05161 4813192 Telefax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.daninject-smith.de Verkauf, Beratung und Service für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör & I N T E R Z O O Service + Logistik GmbH Tranquilizing Equipment Zootiertransporte (Straße, Luft und See), KistenbauBeratung, entsprechend Verkauf undden Service internationalen für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der erforderlichenZootiertransporte Dokumente, (Straße, Vermittlung Luft und von See), Tieren Kistenbau entsprechend den internationalen Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der Celler Str.erforderlichen 2, 29664 Walsrode Dokumente, Vermittlung von Tieren Tel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Str. 2, 29664 Walsrode www.interzoo.deTel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 – 74574 2 e-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] http://www.interzoo.de http://www.daninject-smith.de Vorwort Früheren Auflagen des Quantum Verzeichnis lag eine CD-Rom mit der Druckdatei im PDF-Format bei, welche sich großer Beliebtheit erfreute. Nicht zuletzt aus ökologischen Gründen verzichten wir zukünftig auf eine CD-Rom. Stattdessen kann das Quantum Verzeichnis in digitaler Form über unseren Webshop (www.buchkurier.de) kostenlos heruntergeladen werden. Die Datei darf gerne kopiert und weitergegeben werden. -

ATIC0943 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 0208 2257636 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0943 {By Email} 4 October 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos which we received on 26 September 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “Please can you provide me with a full list of the names of all Zoos in the UK. Under the classification of 'Zoos' I am including any place where a member of the public can visit or observe captive animals: zoological parks, centres or gardens; aquariums, oceanariums or aquatic attractions; wildlife centres; butterfly farms; petting farms or petting zoos. “Please also provide me the date of when each zoo has received its license under the Zoo License act 1981.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on current licensed zoos affected by the Zoo License Act 1981 in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 26 September 2016 (date of request). The information relating to Northern Ireland is not held by APHA. Any potential information maybe held with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland (DAERA-NI). Where there are blanks on the zoo license start date that means the information you have requested is not held by APHA. Please note that the Local Authorities’ Trading Standard departments are responsible for administering and issuing zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981. -

Gait Analysis in Uner Tan Syndrome Cases with Key Symptoms of Quadrupedal Locomotion, Mental Impairment, and Dysarthric Or No Speech

Article ID: WMC005017 ISSN 2046-1690 Gait Analysis in Uner Tan Syndrome Cases with Key Symptoms of Quadrupedal Locomotion, Mental Impairment, and Dysarthric or No Speech Peer review status: No Corresponding Author: Submitting Author: Prof. Uner Tan, Senior Researcher, Cukurova University Medical School , Cukurova University, Medical School, Adana, 01330 - Turkey Article ID: WMC005017 Article Type: Research articles Submitted on: 09-Nov-2015, 01:39:27 PM GMT Published on: 10-Nov-2015, 08:43:08 AM GMT Article URL: http://www.webmedcentral.com/article_view/5017 Subject Categories: NEUROSCIENCES Keywords: Uner Tan syndrome, quadrupedal locomotion, ataxia, gait, lateral sequence, diagonal sequence, evolution, primates How to cite the article: Tan U. Gait Analysis in Uner Tan Syndrome Cases with Key Symptoms of Quadrupedal Locomotion, Mental Impairment, and Dysarthric or No Speech. WebmedCentral NEUROSCIENCES 2015;6(11):WMC005017 Copyright: This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Source(s) of Funding: None Competing Interests: None Additional Files: Illustration 1 ILLUSTRATION 2 ILLUSTRATION 3 ILLUSTRATION 4 ILLUSTRATION 5 ILLUSTRATION 6 WebmedCentral > Research articles Page 1 of 14 WMC005017 Downloaded from http://www.webmedcentral.com on 10-Nov-2015, 08:43:10 AM Gait Analysis in Uner Tan Syndrome Cases with Key Symptoms of Quadrupedal Locomotion, Mental Impairment, and Dysarthric or No Speech Author(s): Tan U Abstract sequence, on the lateral and on the diagonals.” This child typically exhibited straight legs during quadrupedal standing. Introduction: Uner Tan syndrome (UTS) consists of A man with healthy legs walking on all fours was quadrupedal locomotion (QL), impaired intelligence discovered by Childs [3] in Turkey, 1917. -

Rethinking the Evolution of the Human Foot: Insights from Experimental Research Nicholas B

© 2018. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2018) 221, jeb174425. doi:10.1242/jeb.174425 REVIEW Rethinking the evolution of the human foot: insights from experimental research Nicholas B. Holowka* and Daniel E. Lieberman* ABSTRACT presumably owing to their lack of arches and mobile midfoot joints Adaptive explanations for modern human foot anatomy have long for enhanced prehensility in arboreal locomotion (see Glossary; fascinated evolutionary biologists because of the dramatic differences Fig. 1B) (DeSilva, 2010; Elftman and Manter, 1935a). Other studies between our feet and those of our closest living relatives, the great have documented how great apes use their long toes, opposable apes. Morphological features, including hallucal opposability, toe halluces and mobile ankles for grasping arboreal supports (DeSilva, length and the longitudinal arch, have traditionally been used to 2009; Holowka et al., 2017a; Morton, 1924). These observations dichotomize human and great ape feet as being adapted for bipedal underlie what has become a consensus model of human foot walking and arboreal locomotion, respectively. However, recent evolution: that selection for bipedal walking came at the expense of biomechanical models of human foot function and experimental arboreal locomotor capabilities, resulting in a dichotomy between investigations of great ape locomotion have undermined this simple human and great ape foot anatomy and function. According to this dichotomy. Here, we review this research, focusing on the way of thinking, anatomical features of the foot characteristic of biomechanics of foot strike, push-off and elastic energy storage in great apes are assumed to represent adaptations for arboreal the foot, and show that humans and great apes share some behavior, and those unique to humans are assumed to be related underappreciated, surprising similarities in foot function, such as to bipedal walking. -

Conference Main Sponsors-2018

Anatomical variation of habitat related changes in scapular morphology C. Luziga1 and N. Wada2 1Department of Veterinary Anatomy and Pathology, College of Veterinary and Biomedical Sciences, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania 2Laboratory Physiology, Department of Veterinary Sciences, School of Veterinary Medicine, Yamaguchi University, Yamaguchi 753-8558, Japan E-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY The mammalian forelimb is adapted to different functions including postural, locomotor, feeding, exploratory, grooming and defense. Comparative studies on morphology of the mammalian scapula have been performed in an attempt to establish the functional differences in the use of the forelimb. In this study, a total of 102 scapulae collected from 66 species of animals, representatives of all major taxa from rodents, sirenians, marsupials, pilosa, cetaceans, carnivores, ungulates, primates and apes were analyzed. Parameters measured included scapular length, width, position, thickness, area, angles and index. Structures included supraspinous and infraspinous fossae, scapular spine, glenoid cavity, acromium and coracoid processes. Images were taken using computed tomographic (CT) scanning technology (CT-Aquarium, Toshiba and micro CT- LaTheta, Hotachi, Japan) and measurement values acquired and processed using Avizo computer software and CanvasTM 11 ACD systems. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2013. Results obtained showed that there were similar morphological characteristics of scapula in mammals with arboreal locomotion and living in forest and mountainous areas but differed from those with leaping and terrestrial locomotion living in open habitat or savannah. The cause for the statistical grouping of the animals signifies presence of the close relationship between habitat and scapular morphology and in a way that corresponds to type of locomotion and speed. -

APE RESCUE CENTRE Risk Assessment for School & Group

MONKEY WORLD – APE RESCUE CENTRE Risk Assessment for School & Group Educational Visits 2020/21 Please note: We are a primate rescue and rehabilitation centre and not a zoo, as such the majority of our primates have been abused, neglected and exploited. We would be grateful if you could remind your students of this fact prior to entering our park. We have offered our rescued monkeys and apes sanctuary, free from abuse of any kind and we will not tolerate any behaviour from visitors that causes distress to our primates in anyway e.g. shouting, screaming, banging on the viewing windows, running up and down outside enclosures, throwing items into the enclosures, feeding our primates etc. Visitors that do not abide by the rules of entry to the park will be asked to leave and no refund will be given. Risk Assessment Guidance Monkey World operates under the auspices of the Zoo Licensing Act. We are subject to annual inspections from Enforcement Officers who look at the way we take care of our Primates and the safety of Staff and Visitors. The licence has to be renewed every six years. We strongly recommend that group organisers make a pre-visit to Monkey World and carry out their own risk assessment. We allow one free entry per class/group which is available on request when booking your visit. In the event that a pre-visit is impossible, this document provides a general outline of the risks and controls identified. It is essential that all children are supervised throughout their visit to us and that all attending the visit understand the following: the aims and objectives of the visit how to avoid specific dangers and why they must follow rules why safety precautions are in place and standard of behaviour is expected who is responsible for the Group what to do if approached by anyone outside the Group what to do if separated from the Group the time and place of departure of the Group that in an emergency situation e.g. -

University of Illinois

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 3 MAY THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Leahanne M, Sarlo Functional Anatomy and Allometry in the Shoulder of ENTITLED........................................................ Suspensory Primates IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF. BACHELOR OF ARTS LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES 0-1M4 t « w or c o w n w Introduction.....................................................................................................................................1 Dafinibon*..................................................................................................................................... 2 fFunctional m ivw w iiw irwbaola am foriwi irviiiiHbimanual iw 9 jrvafwooaitiona! Vf aai irwbahavlort iiHviw i# in thaahoukter joint complex......................................................................................3 nyvootiua pooioonaiaA^^AlttAAMAl oanainor................................................................................... i4 *4 -TnoOV a awmang.a Ia M AM JI* nwoo—U^AtkA^AA i (snDBDfllluu)/AuMyAlftAlAnAH |At AkJA^AAtlA•wwacwai* |A .............. 4ia i -Tho lar gibbon: KM obate* ]|£.................................................................................15 ANomatry.......................................................................................................................................16 Material* and matooda.....................................................................................................19 -

Why Trot When You Can Walk? an Investigation of the Walk-Trot Transition in the Horse

Why trot when you can walk? An Investigation of the Walk-Trot Transition in the Horse A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State Polytechnic University, Pomona In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science In Biological Sciences By Devin A. J. Johnsen 2003 SIGNATURE PAGE THESIS: Why trot when you can walk? An investigation of the Walk-Trot Transition in the Horse AUTHOR: Devin A. J. Johnsen DATE SUBMITTED: __________________________________________ Department of Biological Sciences Dr. Donald F. Hoyt __________________________________________ Thesis Committee Chair Biological Sciences Dr. Steven J. Wickler __________________________________________ Animal & Veterinary Sciences Dr. Edward A. Cogger __________________________________________ Animal & Veterinary Sciences Dr. Sepehr Eskandari __________________________________________ Biological Sciences ii Abstract Parameters ranging from energetics to kinematics, from muscle function to ground reaction force, have been theorized as triggers for a variety of terrestrial gait transitions. The walk-trot transition represents a change between gaits governed by very different mechanics, as the walk is modeled by the inverted pendulum, while the trot is modeled by the spring-mass model. A set of five criteria was established in order to determine a parameter as a trigger of the walk-trot transition in the horse. In addition, these mechanical models can provide specific predictions about the change in leg length during the stride. Six horses walked and trotted over a range of speeds on a high-speed treadmill. Stride parameters were measured using accelerometers, while sonomicrometry and electromyography measured muscle function of the vastus lateralis. Kinematics of the coxofemoral, femorotibial, tarsal, and metatarsophalangeal joints as well as leg length were determined using a high-speed (125 Hz) camera. -

Ape Rescue Chronicle Three Adults Planet Ape Hoodies Adults Planet Ape T-Shirts All Donations Go Into the 100% Ape Rescue Different Goods Times Per Year

Buy a Twister Buy a travel mug Only Beaker £2.99 each and get your first cold drink FREE Charity No. 1126939 + 20%off refills! Only Redeemable at any café or £7.99 each kiosk in the park. and get your first A PE R ESCUE C HRONICLE Recently, the law has changed regarding Issue: 69 SPRING/SUMMER 2018 hot drink FREE data protection regulation (GDPR) which 20%off refills! aims to improve the way companies + handle customer’s personal data. To see how this affects Monkey World adoptive Redeemable at parents, and the way we use and store customer data, please see our data protection compliance statement any café or kiosk online at www.monkeyworld.org/files/monkeyworldgdpr.pdf. If you have any other questions or concerns about data protection, in the park. please contact us at [email protected] ACCOMMODATION NEAR MONKEY WORLD With a portfolio of over 300 personally selected properties, over 100 of which are pet friendly, Dream Cottages are Dorset’s leading holiday cottage agency. Camping or Glamping Call: 01305 789000 Click: www.dream-cottages.co.uk An award winning site, Longthorns is a small farm nestled White Horse Farm Breachfield B&B next to Monkey World. Join us for camping & glamping in a 01963 210222 07776 043140 relaxed atmosphere. We don’t offer regimented pitches, just camp-fires, stargazing and quiet evenings. Enjoy our wonderful woodland walk, alpacas, chickens, horses and cows. Self-catering accommodation 4 cottages, farmhouse annex Friendly B&B located in the heart of Wool, and lodge in rural Dorset. just 2 mins from Monkey World. -

Linking Gait Dynamics to Mechanical Cost of Legged Locomotion

REVIEW published: 17 October 2018 doi: 10.3389/frobt.2018.00111 Linking Gait Dynamics to Mechanical Cost of Legged Locomotion David V. Lee 1* and Sarah L. Harris 2 1 School of Life Sciences, University of Nevada Las Vegas, Las Vegas, NV, United States, 2 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Nevada Las Vegas, Las Vegas, NV, United States For millenia, legged locomotion has been of central importance to humans for hunting, agriculture, transportation, sport, and warfare. Today, the same principal considerations of locomotor performance and economy apply to legged systems designed to serve, assist, or be worn by humans in urban and natural environments. Energy comes at a premium not only for animals, wherein suitably fast and economical gaits are selected through organic evolution, but also for legged robots that must carry sufficient energy in their batteries. Although a robot’s energy is spent at many levels, from control systems to actuators, we suggest that the mechanical cost of transport is an integral energy expenditure for any legged system—and measuring this cost permits the most direct comparison between gaits of legged animals and robots. Although legged robots have matched or even improved upon total cost of transport of animals, this is typically achieved by choosing extremely slow speeds or by using regenerative mechanisms. Legged robots have not yet reached the low mechanical cost of transport achieved at speeds used by bipedal and quadrupedal animals. Here we consider approaches Edited by: used to analyze gaits and discuss a framework, termed mechanical cost analysis, that Monica A. Daley, can be used to evaluate the economy of legged systems. -

Point-Mass Model of Brachiation

The Journal of Experimental Biology 202, 2609–2617 (1999) 2609 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 1999 JEB1788 A POINT-MASS MODEL OF GIBBON LOCOMOTION JOHN E. A. BERTRAM1,*, ANDY RUINA2, C. E. CANNON3, YOUNG HUI CHANG4 AND MICHAEL J. COLEMAN5 1College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University, USA, 2Theoretical and Applied Mechanics, Cornell University, USA, 3Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Cornell University, USA, 4Department of Integrative Biology, University of California-Berkeley, USA and 5Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Cornell University, USA *Author for correspondence at Department of Nutrition, Food and Exercise Sciences, 436 Sandels Building, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306, USA (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 10 June; published on WWW 13 September 1999 Summary In brachiation, an animal uses alternating bimanual losses due to inelastic collisions of the animal with the support to move beneath an overhead support. Past support are avoided, either because the collisions occur at brachiation models have been based on the oscillations of zero velocity (continuous-contact brachiation) or by a a simple pendulum over half of a full cycle of oscillation. smooth matching of the circular and parabolic trajectories These models have been unsatisfying because the natural at the point of contact (ricochetal brachiation). This model behavior of gibbons and siamangs appears to be far less predicts that brachiation is possible over a large range restricted than so predicted. Cursorial mammals use an of speeds, handhold spacings and gait frequencies with inverted pendulum-like energy exchange in walking, but (theoretically) no mechanical energy cost.