Arthur Seymour Sullivan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com SirArthurSullivan ArthurLawrence,BenjaminWilliamFindon,WilfredBendall \ SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. From the Portrait Pruntfd w 1888 hv Sir John Millais. !\i;tn;;;i*(.vnce$. i-\ !i. W. i ind- i a. 1 V/:!f ;d B'-:.!.i;:. SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN : Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. By Arthur Lawrence. With Critique by B. W. Findon, and Bibliography by Wilfrid Bendall. London James Bowden 10 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, W.C. 1899 /^HARVARD^ UNIVERSITY LIBRARY NOV 5 1956 PREFACE It is of importance to Sir Arthur Sullivan and myself that I should explain how this book came to be written. Averse as Sir Arthur is to the " interview " in journalism, I could not resist the temptation to ask him to let me do something of the sort when I first had the pleasure of meeting ^ him — not in regard to journalistic matters — some years ago. That permission was most genially , granted, and the little chat which I had with J him then, in regard to the opera which he was writing, appeared in The World. Subsequent conversations which I was privileged to have with Sir Arthur, and the fact that there was nothing procurable in book form concerning our greatest and most popular composer — save an interesting little monograph which formed part of a small volume published some years ago on English viii PREFACE Musicians by Mr. -

Vol. 17, No. 4 April 2012

Journal April 2012 Vol.17, No. 4 The Elgar Society Journal The Society 18 Holtsmere Close, Watford, Herts., WD25 9NG Email: [email protected] April 2012 Vol. 17, No. 4 President Editorial 3 Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM ‘... unconnected with the schools’ – Edward Elgar and Arthur Sullivan 4 Meinhard Saremba Vice-Presidents The Empire Bites Back: Reflections on Elgar’s Imperial Masque of 1912 24 Ian Parrott Andrew Neill Sir David Willcocks, CBE, MC Diana McVeagh ‘... you are on the Golden Stair’: Elgar and Elizabeth Lynn Linton 42 Michael Kennedy, CBE Martin Bird Michael Pope Book reviews 48 Sir Colin Davis, CH, CBE Lewis Foreman, Carl Newton, Richard Wiley Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Leonard Slatkin Music reviews 52 Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Julian Rushton Donald Hunt, OBE DVD reviews 54 Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE Richard Wiley Andrew Neill Sir Mark Elder, CBE CD reviews 55 Barry Collett, Martin Bird, Richard Wiley Letters 62 Chairman Steven Halls 100 Years Ago 65 Vice-Chairman Stuart Freed Treasurer Peter Hesham Secretary The Editor does not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, Helen Petchey nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Front Cover: Arthur Sullivan: specially engraved for Frederick Spark’s and Joseph Bennett’s ‘History of the Leeds Musical Festivals’, (Leeds: Fred. R. Spark & Son, 1892). Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. A longer version is available in case you are prepared to do the formatting, but for the present the editor is content to do this. -

George Grove and the Establishment of the Palestine Exploration Fund

Chapter One George Grove and the Establishment of the Palestine Exploration Fund David M. Jacobson Abstract This article surveys the growing thirst for factual evidence relating to the world of the Bible in mid-19th century Britain and early tentative efforts to address this demand. It was against this background that the polymath George Grove sought to establish a secular institution devoted to the multidisciplinary study of the southern Levant based on scientific principles. Evidence is marshalled to show that it was Grove’s exceptional combination of talents—his organizational and networking skills, natural intelligence, and wide interests, including a profound knowledge of the geography of the Bible—that enabled him to recruit some of the most illustrious figures of Victorian Britain to help him realize this ambition in 1865, with the establishment of the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF). Keywords: James Fergusson; George Grove; history of Levantine studies; Palestine Exploration Fund; Arthur Penrhyn Stanley Introduction undertaking, and it was Grove who took on the role of PEF Honorary Secretary (Lipman 1988: 47). In 1865 George Grove (1820–1900), the secretary Twenty-four eminent figures of Victorian of the Crystal Palace, sent out formal invitations society attended the meeting (Lipman 1988: to selected public figures, asking them to 47–9), which was chaired by the Archbishop of attend the preliminary meeting of the Palestine York, William Thomson (1819–1890), a church Exploration Fund (PEF) at the Jerusalem Cham- ber,1 Westminster Abbey, at 5 pm, Friday, 12 disciplinarian who had also distinguished him- May (Conder and Kitchener 1881: 3–4; details self as a logician, earning him election as a are also recorded in the manuscript PEF Minute Fellow of the Royal Society in 1863 (Carlyle Book, Vol. -

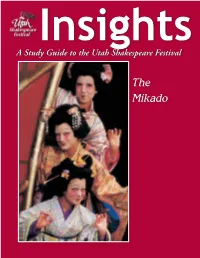

The Mikado the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival The Mikado The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. Insights is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2011, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print Insights, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Erin Annarella (top), Carol Johnson, and Sarah Dammann in The Mikado, 1996 Contents Information on the Play Synopsis 4 CharactersThe Mikado 5 About the Playwright 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play Mere Pish-Posh 8 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Synopsis: The Mikado Nanki-Poo, the son of the royal mikado, arrives in Titipu disguised as a peasant and looking for Yum- Yum. Without telling the truth about who he is, Nanki-Poo explains that several months earlier he had fallen in love with Yum-Yum; however she was already betrothed to Ko-Ko, a cheap tailor, and he saw that his suit was hopeless. -

CHAN 9859 Front.Qxd 31/8/07 10:04 Am Page 1

CHAN 9859 Front.qxd 31/8/07 10:04 am Page 1 CHAN 9859 CHANDOS CHAN 9859 BOOK.qxd 31/8/07 10:06 am Page 2 Sir Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900) AKG 1 In memoriam 11:28 Overture in C major in C-Dur . ut majeur Andante religioso – Allegro molto Suite from ‘The Tempest’, Op. 1 27:31 2 1 No. 1. Introduction 5:20 Andante con moto – Allegro non troppo ma con fuoco 3 2 No. 4. Prelude to Act III 1:58 Allegro moderato e con grazia 4 3 No. 6. Banquet Dance 4:39 Allegretto grazioso ma non troppo – Andante – Allegretto grazioso 5 4 No. 7. Overture to Act IV 5:00 Allegro assai con brio 6 5 No. 10. Dance of Nymphs and Reapers 4:21 Allegro vivace e con grazia 7 6 No. 11. Prelude to Act V 4:21 Andante – Allegro con fuoco – Andante 8 7 No. 12c. Epilogue 1:42 Andante sostenuto 3 CHAN 9859 BOOK.qxd 31/8/07 10:06 am Page 4 Sir Arthur Sullivan: Symphony in E major ‘Irish’ etc. Symphony in E major ‘Irish’ 36:02 Sir Arthur Sullivan would have been return to London a public performance in E-Dur . mi majeur delighted to know that the comic operas he of the complete music followed at the 9 I Andante – Allegro, ma non troppo vivace 13:21 wrote with W.S. Gilbert retain their hold on Crystal Palace Concert on 5 April 1862 10 II Andante espressivo 7:13 popular affection a hundred years after his under the baton of August Manns. -

The Parish of All Saints • Ashmont Liturgical Music

The Parish of All Saints • Ashmont Liturgical Music October 6 The Twentieth Sunday after Pentecost Late Pentecost through Christmas 2013 Communion Service in A minor – Harold Darke The Rev’d Michael J. Godderz, Rector Psalm 37:3-10 Anglican Chant: Joseph Barnby Andrew P. Sheranian, Organist and Master of Choristers Ave verum corpus – Richard Dering Organ Christian Haigh, Organ Scholar Prière à Notre Dame (Suite Gothique) – Léon Boëllmann Michael Raleigh, Archibald T. Davison Fellow Toccata in B minor – Eugène Gigout October 13 The Twenty-First Sunday after Pentecost September 15 The Seventeenth Sunday after Pentecost Missa Brevis – Andrea Gabrieli Communion Service in B minor – T. Tertius Noble Psalm 113 Anglican Chant: Thomas Walmisley Psalm 51:1-11 Anglican Chant: Samuel Wesley North Port – Sacred Harp Ave verum corpus – Edward Elgar Organ Organ Prelude in C major BWV 545 – Johann Sebastian Bach Toccata in D minor – Johann Sebastian Bach Fugue in C major BWV 545 – Johann Sebastian Bach Fugue in D minor ‘Dorian’ – Johann Sebastian Bach October 20 The Twenty-Second Sunday after Pentecost September 22 The Eighteenth Sunday after Pentecost Communion Service in B-flat and F major – Charles V. Stanford Communion Service in F – William H. Harris Psalm 121 Anglican Chant: Henry Walford Davies Psalm 138 Anglican Chant: Samuel Sebastian Wesley I will lift up mine eyes – Leo Sowerby Listen, sweet dove – Grayston Ives Organ Organ Prelude in G minor – Johannes Brahms Adagio (Sonata I) – Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy Fugue in G minor – Johannes Brahms Allegro assai vivace (Sonata I) – Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy October 27 The Twenty-Third Sunday after Pentecost September 29 The Feast of St. -

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten Through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums

A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughn Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Jensen, Joni Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 21:33:53 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193556 A COMPARISON OF ORIGINS AND INFLUENCES IN THE MUSIC OF VAUGHAN WILLIAMS AND BRITTEN THROUGH ANALYSIS OF THEIR FESTIVAL TE DEUMS by Joni Lynn Jensen Copyright © Joni Lynn Jensen 2005 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC AND DANCE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 5 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Joni Lynn Jensen entitled A Comparison of Origins and Influences in the Music of Vaughan Williams and Britten through Analysis of Their Festival Te Deums and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Bruce Chamberlain _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Elizabeth Schauer _______________________________________________________________________ Date: July 29, 2005 Josef Knott Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 77, 1957-1958, Subscription

*l'\ fr^j BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON 24 G> X will MIIHIi H tf SEVENTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1957-1958 BAYARD TUCEERMAN. JR. ARTHUR J. ANDERSON ROBERT T. FORREST JULIUS F. HALLER ARTHUR J. ANDERSON, JR. HERBERT 8. TUCEERMAN J. DEANE SOMERVILLE It takes only seconds for accidents to occur that damage or destroy property. It takes only a few minutes to develop a complete insurance program that will give you proper coverages in adequate amounts. It might be well for you to spend a little time with us helping to see that in the event of a loss you will find yourself protected with insurance. WHAT TIME to ask for help? Any time! Now! CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO. RICHARD P. NYQUIST in association with OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description 108 Water Street Boston 6, Mast. LA fayette 3-5700 SEVENTY-SEVENTH SEASON, 1957-1958 Boston Symphony Orchestra CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor CONCERT BULLETIN with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk Copyright, 1958, by Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot President Jacob J. Kaplan Vice-President Richard C. Paine Treasurer Talcott M. Banks Michael T. Kelleher Theodore P. Ferris Henry A. Laughlin Alvan T. Fuller John T. Noonan Francis W. Hatch Palfrey Perkins Harold D. Hodgkinson Charles H. Stockton C. D. Jackson Raymond S. Wilkins E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Oliver Wolcott TRUSTEES EMERITUS Philip R. Allen M. A. DeWolfe Howe N. Penrose Hallowell Lewis Perry Edward A. Taft Thomas D. -

Beethoven's Fourth Symphony: Comparative Analysis of Recorded Performances, Pp

BEETHOVEN’S FOURTH SYMPHONY: RECEPTION, AESTHETICS, PERFORMANCE HISTORY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Mark Christopher Ferraguto August 2012 © 2012 Mark Christopher Ferraguto BEETHOVEN’S FOURTH SYMPHONY: RECEPTION, AESTHETICS, PERFORMANCE HISTORY Mark Christopher Ferraguto, PhD Cornell University 2012 Despite its established place in the orchestral repertory, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 4 in B-flat, op. 60, has long challenged critics. Lacking titles and other extramusical signifiers, it posed a problem for nineteenth-century critics espousing programmatic modes of analysis; more recently, its aesthetic has been viewed as incongruent with that of the “heroic style,” the paradigm most strongly associated with Beethoven’s voice as a composer. Applying various methodologies, this study argues for a more complex view of the symphony’s aesthetic and cultural significance. Chapter I surveys the reception of the Fourth from its premiere to the present day, arguing that the symphony’s modern reputation emerged as a result of later nineteenth-century readings and misreadings. While the Fourth had a profound impact on Schumann, Berlioz, and Mendelssohn, it elicited more conflicted responses—including aporia and disavowal—from critics ranging from A. B. Marx to J. W. N. Sullivan and beyond. Recent scholarship on previously neglected works and genres has opened up new perspectives on Beethoven’s music, allowing for a fresh appreciation of the Fourth. Haydn’s legacy in 1805–6 provides the background for Chapter II, a study of Beethoven’s engagement with the Haydn–Mozart tradition. -

Sir John Goss. 1800-1880 (Concluded) Author(S): F

Sir John Goss. 1800-1880 (Concluded) Author(s): F. G. E. Source: The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol. 42, No. 700 (Jun. 1, 1901), pp. 375-383 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3368650 Accessed: 05-11-2015 01:21 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 137.189.170.231 on Thu, 05 Nov 2015 01:21:39 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE MUSICAL TIMES. JUNEI, I90I. 375 deprecatoryabout this accomplishmentof hers, SIR JOHN GOSS. in which,however, she acquittedherself charm- I800-I880. ingly. Her favouritemusicianwas Mendelssohn, who had greatly pleased her in early days as a (Concludedfrom page 23 I .) man. She would have nothing to say, until BEFOREresuming this biographicalsketch, a quite late in life7to Wagner or Brahms, and slight error in its Erst instalment (p. 225), once dismissed them all in one of her abrupt kindly pointed out by Mr. -

The Parish of All Saints • Ashmont Liturgical Music

The Parish of All Saints • Ashmont Liturgical Music February 5 The Fifth Sunday after the Epiphany Epiphanytide 2017 Missa brevis – Philip Radcliffe The Rev’d Michael J. Godderz, Rector Psalm 27:1-7 Anglican Chant: John Goss Andrew P. Sheranian, Organist and Master of Choristers Pater noster – Charles Villiers Stanford Organ Michael Raleigh, Archibald T. Davison Fellow Intermezzo (Sonata VIII) – Josef Gabriel Rheinberger Tempo moderato (Sonata IV) – Josef Gabriel Rheinberger January 6 The Epiphany of Our Lord Jesus Christ Missa ad Præsepe – George Malcolm February 5 The Feast of the Presentation – Candlemas Evensong Psalm 72:1-2, 10-17 Anglican Chant: Herbert Howells With the Choir of All Saints’, Worcester There shall a star appear – Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy Preces and Responses – Bernard Rose Organ Psalm 84 Anglican Chant: C. Hubert H. Parry Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern – Dietrich Buxtehude I: Allegro (Symphony II) – Louis Vierne Evening Service for Gloucester Cathedral – Herbert Howells Behold, O God our defender – Herbert Howells Organ January 8 The Feast of the Baptism of Christ Pièce d’Orgue – Johann Sebastian Bach Messe ‘Cum jubilo’ – Maurice Duruflé Sinfonia (from Cantata No. 29) – Johann Sebastian Bach Psalm 89:20-29 Anglican Chant: Samuel Sebastian Wesley Sicut cervus – Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina February 12 The Sixth Sunday after the Epiphany Organ Mass of the Quiet Hour – George Oldroyd Prélude sur l’Introit d’Épiphanie – Maurice Duruflé Méditation – Maurice Duruflé Psalm 119:9-16 Anglican Chant: C.H. Lloyd O