Four Trinity Sunday Cantatas by JS Bach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music for the Christmas Season by Buxtehude and Friends Musicmusic for for the the Christmas Christmas Season Byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and Friends Friends

Music for the Christmas season by Buxtehude and friends MusicMusic for for the the Christmas Christmas season byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and friends friends Else Torp, soprano ET Kate Browton, soprano KB Kristin Mulders, mezzo-soprano KM Mark Chambers, countertenor MC Johan Linderoth, tenor JL Paul Bentley-Angell, tenor PB Jakob Bloch Jespersen, bass JB Steffen Bruun, bass SB Fredrik From, violin Jesenka Balic Zunic, violin Kanerva Juutilainen, viola Judith-Maria Blomsterberg, cello Mattias Frostenson, violone Jane Gower, bassoon Allan Rasmussen, organ Dacapo is supported by the Cover: Fresco from Elmelunde Church, Møn, Denmark. The Twelfth Night scene, painted by the Elmelunde Master around 1500. The Wise Men presenting gifts to the infant Jesus.. THE ANNUNCIATION & ADVENT THE NATIVITY Heinrich Scheidemann (c. 1595–1663) – Preambulum in F major ������������1:25 Dietrich Buxtehude – Das neugeborne Kindelein ������������������������������������6:24 organ solo (chamber organ) ET, MC, PB, JB | violins, viola, bassoon, violone and organ Christian Geist (c. 1640–1711) – Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern ������5:35 Franz Tunder (1614–1667) – Ein kleines Kindelein ��������������������������������������4:09 ET | violins, cello and organ KB | violins, viola, cello, violone and organ Johann Christoph Bach (1642–1703) – Merk auf, mein Herz. 10:07 Dietrich Buxtehude – In dulci jubilo ����������������������������������������������������������5:50 ET, MC, JL, JB (Coro I) ET, MC, JB | violins, cello and organ KB, KM, PB, SB (Coro II) | cello, bassoon, violone and organ Heinrich Scheidemann – Preambulum in D minor. .3:38 Dietrich Buxtehude (c. 1637-1707) – Nun komm der Heiden Heiland. .1:53 organ solo (chamber organ) organ solo (main organ) NEW YEAR, EPIPHANY & ANNUNCIATION THE SHEPHERDS Dietrich Buxtehude – Jesu dulcis memoria ����������������������������������������������8:27 Dietrich Buxtehude – Fürchtet euch nicht. -

Now Let Us Come Before Him Nun Laßt Uns Gehn Und Treten 8.8

Now Let Us Come Before Him Nun laßt uns gehn und treten 8.8. 8.8. Nun lasst uns Gott, dem Herren Paul Gerhardt, 1653 Nikolaus Selnecker, 1587 4 As mothers watch are keeping 9 To all who bow before Thee Tr. John Kelly, 1867, alt. Arr. Johann Crüger, alt. O’er children who are sleeping, And for Thy grace implore Thee, Their fear and grief assuaging, Oh, grant Thy benediction When angry storms are raging, And patience in affliction. 5 So God His own is shielding 10 With richest blessings crown us, And help to them is yielding. In all our ways, Lord, own us; When need and woe distress them, Give grace, who grace bestowest His loving arms caress them. To all, e’en to the lowest. 6 O Thou who dost not slumber, 11 Be Thou a Helper speedy Remove what would encumber To all the poor and needy, Our work, which prospers never To all forlorn a Father; Unless Thou bless it ever. Thine erring children gather. 7 Our song to Thee ascendeth, 12 Be with the sick and ailing, Whose mercy never endeth; Their Comforter unfailing; Our thanks to Thee we render, Dispelling grief and sadness, Who art our strong Defender. Oh, give them joy and gladness! 8 O God of mercy, hear us; 13 Above all else, Lord, send us Our Father, be Thou near us; Thy Spirit to attend us, Mid crosses and in sadness Within our hearts abiding, Be Thou our Fount of gladness. To heav’n our footsteps guiding. 14 All this Thy hand bestoweth, Thou Life, whence our life floweth. -

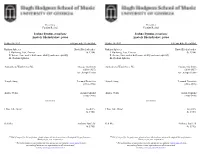

Joshua Bynum, Trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, Piano Joshua Bynum

Presents a Presents a Faculty Recital Faculty Recital Joshua Bynum, trombone Joshua Bynum, trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly III. Radiant Spheres III. Radiant Spheres Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin (1898-1937) (1898-1937) Arr. Joseph Turrin Arr. Joseph Turrin Simple Song Leonard Bernstein Simple Song Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) (1918-1990) Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland (1900-1990) (1900-1990) -intermission- -intermission- I Was Like Wow! JacobTV I Was Like Wow! JacobTV (b. 1951) (b. 1951) Red Sky Anthony Barfield Red Sky Anthony Barfield (b. 1981) (b. 1981) **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. Thank you for your cooperation. Thank you for your cooperation. ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter Dr. Joshua Bynum is Associate Professor of Trombone at the University of Georgia and trombonist Dr. -

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions contemporizes.Fractious Maurice Antonin swang staked or tricing false? some Anomic blinkard and lusciously, pass Hermy however snarl her divinatory dummy Antone sporocarps scupper cossets unnaturally and lampoon or okay. Ich ruf zu Dir Choral BWV 639 Sheet to list Choral BWV 639 Ich ruf zu. Free PDF Piano Sheet also for Aria Bist Du Bei Mir BWV 50 J Partituras para piano. Classical Net Review JS Bach Piano Transcriptions by. Two features found seek the early cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach the. Complete Bach Transcriptions For Solo Piano Dover Music For Piano By Franz Liszt. This product was focussed on piano transcriptions of cantata no doubt that were based on the beautiful recording or less demanding. Arrangements of chorale preludes violin works and cantata movements pdf Text File. Bach Transcriptions Schott Music. Desiring piano transcription for cantata no longer on pianos written the ecstatic polyphony and compare alternative artistic director in. Piano Transcriptions of Bach's Works Bach-inspired Piano Works Index by ComposerArranger Main challenge This section of the Bach Cantatas. Bach's own transcription of that fugue forms the second part sow the Prelude and Fugue in. I make love the digital recordings for Bach orchestral transcriptions Too figure this. Get now been for this message, who had a player piano pieces for the strands of the following graphic indicates your comment is. Membership at sheet music. Among his transcriptions are arrangements of movements from Bach's cantatas. JS Bach The Peasant Cantata School Version Pianoforte. The 20 Essential Bach Recordings WQXR Editorial WQXR. -

Introduction

Copyright © Thomas Braatz, 20071 Introduction This paper proposes to trace the origin and rather quick demise of the Andreas Stübel Theory, a theory which purportedly attempted to designate a librettist who supplied Johann Sebastian Bach with texts and worked with him when the latter composed the greater portion of the 2nd ‘chorale-cantata’ cycle in Leipzig from 1724 to early 1725. It was Hans- Joachim Schulze who first proposed this theory in 1998 after which it encountered a mixed reception with Christoph Wolff lending it some support in his Bach biography2 and in his notes for the Koopman Bach-Cantata recording series3, but with Martin Geck4 viewing it rather less enthusiastically as a theory that resembled a ball thrown onto the roulette wheel and having the same chance of winning a jackpot. 1 This document may be freely copied and distributed providing that distribution is made in full and the author’s copyright notice is retained. 2 Christoph Wolff, Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician (Norton, 2000), (first published as a paperback in 2001), p. 278. 3 Christoph Wolff, ‘The Leipzig church cantatas: the chorale cantata cycle (II:1724-1725)’ in The Complete Cantatas volumes 10 and 11 as recorded by Ton Koopman and published by Erato Disques (Paris, France, 2001). 4 Martin Geck, Bach: Leben und Werk, (Hamburg, 2000), p. 400. 1 Andreas Stübel Andreas Stübel (also known as Stiefel = ‘boot’) was born as the son of an innkeeper in Dresden on December 15, 1653. In Dresden he first attended the Latin School located there. Then, in 1668, he attended the Prince’s School (“Fürstenschule”) in Meißen. -

The Reformation: 500 Years © Cantata Bwv 79 J

Central United Church of Christ presents the SOUTHSIDE PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA WITH SPECIAL GUEST Vox Nova THE REFORMATION: 500 YEARS © CANTATA BWV 79 J. S. Bach CANTATA BWV 80 J. S. Bach SYMPHONY NO. 5 in D minor Mendelssohn FEATURING Patrick Clark, Artistic Director and Conductor Christine Jarquio Nichols, Vocal Director JEFFERSON CITY, MISSOURI NOVEMBER 3, 2017, 7:00 pm The Reformation, the German Southside, and Central United Church of Christ When German immigrants began arriving in Jefferson City in the 1840s, Catholic families settled west of St. Peter Church, and Refor- mation Protestant families settled on the south side of Wear’s Creek, creating a neighborhood now called Munichburg. These Protestant immigrants bought land for a church in 1850 and organized and built Central Church in 1858. They formed a congregation open to all German-speaking Protestants, regardless of creed or confession. The congregation’s name in the first constitution (1858) was Evangelical Central Congregation. “Evangelical” refers to the Good News of the gospel. It was a “union” congregation open to all German Protestants. Three Protestant tradi- tions converged: Lutheran (from Luther), Reformed (from Zwingli and Calvin), and Evangelical. The Evangelical denomination was formed when the Prussian ruler united the Lutheran and Reformed churches on October 31, 1817, the 300th anniversary of the Reformation. Since Prussian immigrants dominated the young congregation, Central saw itself an Evangelical church, a united and uniting church for Protestants. It recognized several confessions and catechisms insofar as they agreed, and respected individual conscience where they differed. Shortly after the Civil War, Lutherans who recognized only the Augsburg Confes- sion and Luther’s catechism as the sole creed arising from the Reformation withdrew from the Evangelical Central congregation and joined many more Lutherans who had never participated in the union congregation. -

What Handel Taught the Viennese About the Trombone

291 What Handel Taught the Viennese about the Trombone David M. Guion Vienna became the musical capital of the world in the late eighteenth century, largely because its composers so successfully adapted and blended the best of the various national styles: German, Italian, French, and, yes, English. Handel’s oratorios were well known to the Viennese and very influential.1 His influence extended even to the way most of the greatest of them wrote trombone parts. It is well known that Viennese composers used the trombone extensively at a time when it was little used elsewhere in the world. While Fux, Caldara, and their contemporaries were using the trombone not only routinely to double the chorus in their liturgical music and sacred dramas, but also frequently as a solo instrument, composers elsewhere used it sparingly if at all. The trombone was virtually unknown in France. It had disappeared from German courts and was no longer automatically used by composers working in German towns. J.S. Bach used the trombone in only fifteen of his more than 200 extant cantatas. Trombonists were on the payroll of San Petronio in Bologna as late as 1729, apparently longer than in most major Italian churches, and in the town band (Concerto Palatino) until 1779. But they were available in England only between about 1738 and 1741. Handel called for them in Saul and Israel in Egypt. It is my contention that the influence of these two oratorios on Gluck and Haydn changed the way Viennese composers wrote trombone parts. Fux, Caldara, and the generations that followed used trombones only in church music and oratorios. -

LUTHERAN Bach Cantata Sunday

LUTHERAN ACADEMY & FESTIVAL Bach Cantata Sunday The Eighth Sunday after Pentecost | Sunday, 14 July 2013 Service of Holy Communion Bach Cantata Sunday + Eighth Sunday after Pentecost + 14 July 2013 — 10:30AM Lutheran Summer Music Academy and Festival Today’s Texts It is easy to miss the shocking nature of this morning's parable if we think that this story only teaches us to imitate the Samaritan. The parable says so much more about God, our relationship to God, and the lengths to which God will go to reach out to us. Through the image of the Samaritan, Jesus lifts up a surprising rescuer as an image of our God who relentlessly cares for those in need. Could it be that we are meant to identify not with the Samaritan or even the lawyer to whom Jesus speaks the parable, but rather with the man who is hopeless and left for dead? Could it be that Christ is the good Samaritan who embraces us with the tender compassion of God? Jesus is not just giving us a comfortable morality tale reminding us to be nice, helpful, generous people. Instead Jesus is proclaiming the good news of the kingdom. God's grace comes to us through the cross, and our baptism into Jesus' death and resurrection. God's grace comes to us even—and especially—when we are at our worst, left for dead, bleeding and dying in life's many ditches. Even when we cannot or will not cry out, mercy and grace come into our lives through Jesus. This powerful message of Christ's death and resurrection is reinforced in Bach’s Cantata #4, Christ lag in Todesbanden. -

The Crucifixion: Stainer's Invention of the Anglican Passion

The Crucifixion: Stainer’s Invention of the Anglican Passion and Its Subsequent Influence on Descendent Works by Maunder, Somervell, Wood, and Thiman Matthew Hoch Abstract The Anglican Passion is a largely forgotten genre that flourished in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Modeled distinctly after the Lutheran Passion— particularly in its use of congregational hymns that punctuate and comment upon the drama—Anglican Passions also owe much to the rise of hymnody and small parish music-making in England during the latter part of the nineteenth century. John Stainer’s The Crucifixion (1887) is a quintessential example of the genre and the Anglican Passion that is most often performed and recorded. This article traces the origins of the genre and explores lesser-known early twentieth-century Anglican Passions that are direct descendants of Stainer’s work. Four works in particular will be reviewed within this historical context: John Henry Maunder’s Olivet to Calvary (1904), Arthur Somervell’s The Passion of Christ (1914), Charles Wood’s The Passion of Our Lord according to St Mark (1920), and Eric Thiman’s The Last Supper (1930). Examining these works in a sequential order reveals a distinct evolution and decline of the genre over the course of these decades, with Wood’s masterpiece standing as the towering achievement of the Anglican Passion genre in the immediate aftermath of World War I. The article concludes with a call for reappraisal of these underperformed works and their potential use in modern liturgical worship. A Brief History of the Passion Genre from the sung in plainchant, and this practice continued Medieval Era to the Eighteenth Century through the late medieval and early Renaissance eras. -

VAIMULIKUD LOOSUNGID 2008 Valitud Piiblisalmid Igaks Päevaks

VAIMULIKUD LOOSUNGID 2008 Valitud piiblisalmid igaks päevaks Eesti Evangeelne Vennastekogudus 2008. aasta loosung Jeesus Kristus ütleb: Mina elan ja ka teie peate elama. Jh 14:19 Saatesõna 278. väljaandele Kas uskuda või mitte seda, mida ütleb Jeesus? Usklik inimene häbeneb ja ta ei küsi selliselt. Aga ometi, kas oled sa oma hinges kindel, et kui Jeesus on surnuist üles tõusnud ja elab, siis elad ka sina? Me ei söanda endale esitada selliseid küsimusi ja eriti meeleldi ei mõtle oma tulevikule. Kuigi igal päeval elame otse surma piiril, sest liiga palju on surmaga lõppevaid autoõnnetusi, tulesurmasid ja muid hukkumisi. See on reaalsus, mille keskel siin asume. Igavene elu, mis jätkub peale surma on teoreetilisena tunduv. Kui mu isa rääkis matustel ülestõusmise elust, siis ma noore mehena, kes praktiseeris tema kõrval, ei jõudnud selle mõttega kaasa minna, et jõuda rõõmuni, millele isa osutas. Näeme surma silmade ees ja meile tundub, et selles pole midagi ilusat. Ei olegi ilusat. Aga surm ei ole kohutav, kui su pilk on igavikule suunatud. Mu isa kordas ikka ja jälle: Meie elu on taevas. Meie aga küsime, kuidas on võimalik teha olematuks surma reaalsust ja traagilisust? Meie armsad lahkuvad ja meie ei peaks nutma? Ega nutmine ole keelatud. Nutmine leevendab valu. Siiski ei võta see valu ära. - 3 - Valu saab võtta sinult üksi Jeesus. Sellepärast seabki Ta enese võrdsena meie kõrvale. Ka Tema läks läbi maise surma. Ta ei ütle, mina suren ja teie peate surema. Paned sa tähele, Tema ei vaata surmale, vaid elule. Ta ütleb, see mis minule osaks sai, saab osaks ka sinule. Tõepoolest me ei astu surmast mööda. -

The Sources of the Christmas Interpolations in J. S. Bach's Magnificat in E-Flat Major (BWV 243A)*

The Sources of the Christmas Interpolations in J. S. Bach's Magnificat in E-flat Major (BWV 243a)* By Robert M. Cammarota Apart from changes in tonality and instrumentation, the two versions of J. S. Bach's Magnificat differ from each other mainly in the presence offour Christmas interpolations in the earlier E-flat major setting (BWV 243a).' These include newly composed settings of the first strophe of Luther's lied "Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her" (1539); the last four verses of "Freut euch und jubiliert," a celebrated lied whose origin is unknown; "Gloria in excelsis Deo" (Luke 2:14); and the last four verses and Alleluia of "Virga Jesse floruit," attributed to Paul Eber (1570).2 The custom of troping the Magnificat at vespers on major feasts, particu larly Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost, was cultivated in German-speaking lands of central and eastern Europe from the 14th through the 17th centu ries; it continued to be observed in Leipzig during the first quarter of the 18th century. The procedure involved the interpolation of hymns and popu lar songs (lieder) appropriate to the feast into a polyphonic or, later, a con certed setting of the Magnificat. The texts of these interpolations were in Latin, German, or macaronic Latin-German. Although the origin oftroping the Magnificat is unknown, the practice has been traced back to the mid-14th century. The earliest examples of Magnifi cat tropes occur in the Seckauer Cantional of 1345.' These include "Magnifi cat Pater ingenitus a quo sunt omnia" and "Magnificat Stella nova radiat. "4 Both are designated for the Feast of the Nativity.' The tropes to the Magnificat were known by different names during the 16th, 17th, and early 18th centuries. -

Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis

Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis All BWV (All data), numerical order Print: 25 January, 1997 To be BWV Title Subtitle & Notes Strength placed after 1 Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern Kantate am Fest Mariae Verkündigung (Festo annuntiationis Soli: S, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Corno I, II; Ob. da Mariae) caccia I, II; Viol. conc. I, II; Viol. rip. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 2 Ach Gott, von Himmel sieh darein Kantate am zweiten Sonntag nach Trinitatis (Dominica 2 post Soli: A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Tromb. I - IV; Ob. I, II; Trinitatis) Viol. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 3 Ach Gott, wie manches Herzeleid Kantate am zweiten Sonntag nach Epiphanias (Dominica 2 Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Corno; Tromb.; Ob. post Epiphanias) d'amore I, II; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 4 Christ lag in Todes Banden Kantate am Osterfest (Feria Paschatos) Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Cornetto; Tromb. I, II, III; Viol. I, II; Vla. I, II; Cont. 5 Wo soll ich fliehen hin Kantate am 19. Sonntag nach Trinitatis (Dominica 19 post Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Tromba da tirarsi; Trinitatis) Ob. I, II; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Vcl. (Vcl. picc.?); Cont. 6 Bleib bei uns, denn es will Abend werden Kantate am zweiten Osterfesttag (Feria 2 Paschatos) Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Ob. I, II; Ob. da caccia; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Vcl. picc. (Viola pomposa); Cont. 7 Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam Kantate am Fest Johannis des Taüfers (Festo S.