Peripheral Giant Cell Granuloma of the Jaws As First Sign of Primary Hyperparathyroidism: a Case Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oralmedicine

116 Test 98.2 ORAL MEDICINE Developmental Mandibular Salivary Gland Defect The Importance of Clinical Evaluation developmental mandibular salivary gland defect (also known as static A bone cyst, static bone defect, Stafne bone cavity, latent bone cyst, latent bone defect, idiopathic bone cavity, developmen- tal submandibular gland defect of the mandible, aberrant salivary gland defect in the mandible, and lingual mandibular bone Sako Ohanesian, concavity) is a deep, well-defined depression DDS in the lingual surface of the posterior body of the mandible. More precisely, the most common location is within the submandibu- lar gland fossa and often close to the inferi- or border of the mandible. In developmental bone defects investigated surgically, an aberrant lobe of the submandibular gland extends into the bony depression. First recognized by Dr. Edward Stafne in 1942, numerous cases of developmental mandibular salivary gland defect have since been reported, and the lesion should not be considered rare.1 In a study of 4963 pan- Most authorities now agree that this entity is a congenital defect, although it has rarely been observed in children and its precise anatomic nature is still uncertain. oramic images of adult patients, 18 cases of Figure 1. CT slices/panoramic views showing a well-defined radiolucent lesion in the right mandible. salivary gland depression were found by Karmiol and Walsh2, an incidence of nearly 0.4%. Most authorities now agree that this The margins of the radiolucent defect are around an extension of salivary tissue. This entity is a congenital defect, although it has well-defined by a dense radiopaque line. -

Peripheral Giant Cell Reparative Granuloma of Maxilla in a Patient with Aggressive Periodontitis

Peripheral Giant Cell Reparative Granuloma of Maxilla in a Patient with Aggressive Periodontitis E Cayci1, B Kan2, E Guzeldemir-Akcakanat1, B Muezzinoglu3 1Department of Periodontology, Kocaeli University, Faculty of Dentistry, Kocaeli, Turkey. 2Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Kocaeli University, Faculty of Dentistry, Kocaeli, Turkey. 3Department of Pathology, Kocaeli University, School of Medicine, Kocaeli, Turkey. Abstract Peripheral giant cell reparative granuloma is a reactive and rare lesion of oral cavity with unknown etiology which is derived from periosteum and periodontal ligament and occurs frequently in young adults. Inflammation or trauma is underlying causative factor of reactive proliferation. In the present case report, a 35 year-old male with aggressive periodontitis and peripheral giant cell reparative granuloma is presented. The patient applied to our clinic with a complaining about a big nodule at his palate. The lesion was pedunculated and localized at his right maxilla between #16 and #17 which arose from distal aspect of #16, and the surface of the lesion was hyperkeratotic and the lesion was measured 22 x 30 mm at the largest diameter. He also had severe generalized aggressive periodontitis and hypertension. Amoxicillin clavulanate 625 mg, three times a day, metronidazole 500 mg three times a day and 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate oral rinse, twice a day for a week, were prescribed to the patient. Then, scaling and root planing were performed along with systemic antibiotic treatment and he scheduled for surgery. The lesion was excised completely and #16 was extracted. After the healing period, periodontal surgery was planned for the treatment of aggressive periodontitis. Obtained tissue specimen was sent for histopathological examination. -

Iii Bds Oral Pathology and Microbiology

III BDS ORAL PATHOLOGY AND MICROBIOLOGY Theory: 120 Hours ORAL PATHOLOGY MUST KNOW 1. Benign and Malignant Tumours of the Oral Cavity (30 hrs) a. Benign tumours of epithelial tissue origin - Papilloma, Keratoacanthoma, Nevus b. Premalignant lesions and conditions: - Definition, classification - Epithelial dysplasia - Leukoplakia, Carcinoma in-situ, Erythroplakia, Palatal changes associated with reverse smoking, Oral submucous fibrosis c. Malignant tumours of epithelial tissue origin - Basal Cell Carcinoma, Epidermoid Carcinoma (Including TNM staging), Verrucous carcinoma, Malignant Melanoma. d. Benign tumours of connective tissue origin : - Fibroma, Giant cell Fibroma, Peripheral and Central Ossifying Fibroma, Lipoma, Haemangioma (different types). Lymphangioma, Chondroma, Osteoma, Osteoid Osteoma, Benign Osteoblastoma, Tori and Multiple Exostoses. e. Tumour like lesions of connective tissue origin : - Peripheral & Central giant cell granuloma, Pyogenic granuloma, Peripheral ossifying fibroma f. Malignant Tumours of Connective tissue origin : - Fibrosarcoma, Chondrosarcoma, Kaposi's Sarcoma Ewing's sarcoma, Osteosarcoma Hodgkin's and Non Hodgkin's L ymphoma, Burkitt's Lymphoma, Multiple Myeloma, Solitary Plasma cell Myeloma. g. Benign Tumours of Muscle tissue origin : - Leiomyoma, Rhabdomyoma, Congenital Epulis of newborn, Granular Cell tumor. h. Benign and malignant tumours of Nerve Tissue Origin - Neurofibroma & Neurofibromatosis-1, Schwannoma, Traumatic Neuroma, Melanotic Neuroectodermal tumour of infancy, Malignant schwannoma. i. Metastatic -

Oral Path Questions

Oral Pathology Oral Pathology • Developmental Conditions • Mucosal Lesions—Reactive • Mucosal Lesions—Infections • Mucosal Lesions—Immunologic Diseases • Mucosal Lesions—Premalignant • Mucosal Lesions—Malignant • CT Tumors—Benign • CT Tumors—Malignant • Salivary Gland Diseases—Reactive • Salivary Gland Diseases—Benign • Salivary Gland Diseases—Malignant • Lymphoid Neoplasms • Odontogenic Cysts • Odontogenic Tumors • Bone Lesions—Fibro-Osseous • Bone Lesions—Giant Cell • Bone Lesions—Inflammatory • Bone Lesions—Malignant • Hereditary Conditions #1 One of the primary etiologic agents of aphthous stomatitis is proposed to be: A. Cytomegalovirus B. Staphylococcus C. Herpes simplex D. Human leukocyte antigen E. Candidiasis #1 One of the primary etiologic agents of aphthous stomatitis is proposed to be: A. Cytomegalovirus B. Staphylococcus C. Herpes simplex D. Human leukocyte antigen E. Candidiasis #2 Intracellular viral inclusions are seen in tissue specimens of which of the following? A. Solar cheilitis B. Minor aphthous ulcers C. Geographic tongue D. Hairy leukoplaKia E. White sponge nevus #2 Intracellular viral inclusions are seen in tissue specimens of which of the following? A. Solar cheilitis B. Minor aphthous ulcers C. Geographic tongue D. Hairy leukoplakia E. White sponge nevus #3 Sjogren’s Syndrome has been linKed to which of the following malignancies? A. Leukemia B. Lymphoma C. Pleomorphic adenoma D. Osteosarcoma #3 Sjogren’s Syndrome has been linKed to which of the following malignancies? A. Leukemia B. Lymphoma C. Pleomorphic adenoma D. Osteosarcoma #4 Acantholysis, resulting from desmosome weaKening by autoantibodies directed against the protein desmoglein, is the disease mechanism attributed to which of the following? A. Epidermolysis bullosa B. Mucous membrane pemphigoid C. Pemphigus vulgaris D. Herpes simplex infections E. -

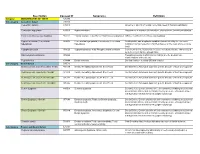

Oral Pathology Final Exam Review Table Tuanh Le & Enoch Ng, DDS

Oral Pathology Final Exam Review Table TuAnh Le & Enoch Ng, DDS 2014 Bump under tongue: cementoblastoma (50% 1st molar) Ranula (remove lesion and feeding gland) dermoid cyst (neoplasm from 3 germ layers) (surgical removal) cystic teratoma, cyst of blandin nuhn (surgical removal down to muscle, recurrence likely) Multilocular radiolucency: mucoepidermoid carcinoma cherubism ameloblastoma Bump anterior of palate: KOT minor salivary gland tumor odontogenic myxoma nasopalatine duct cyst (surgical removal, rare recurrence) torus palatinus Mixed radiolucencies: 4 P’s (excise for biopsy; curette vigorously!) calcifying odontogenic (Gorlin) cyst o Pyogenic granuloma (vascular; granulation tissue) periapical cemento-osseous dysplasia (nothing) o Peripheral giant cell granuloma (purple-blue lesions) florid cemento-osseous dysplasia (nothing) o Peripheral ossifying fibroma (bone, cartilage/ ossifying material) focal cemento-osseous dysplasia (biopsy then do nothing) o Peripheral fibroma (fibrous ct) Kertocystic Odontogenic Tumor (KOT): unique histology of cyst lining! (see histo notes below); 3 important things: (1) high Multiple bumps on skin: recurrence rate (2) highly aggressive (3) related to Gorlin syndrome Nevoid basal cell carcinoma (Gorlin syndrome) Hyperparathyroidism: excess PTH found via lab test Neurofibromatosis (see notes below) (refer to derm MD, tell family members) mucoepidermoid carcinoma (mixture of mucus-producing and squamous epidermoid cells; most common minor salivary Nevus gland tumor) (get it out!) -

Adverse Effects of Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Substances

Benign? Not So Fast: Challenging Oral Diseases presented with DDX June 21st 2018 Dolphine Oda [email protected] Tel (206) 616-4748 COURSE OUTLINE: Five Topics: 1. Oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)-Variability in Etiology 2. Oral Ulcers: Spectrum of Diseases 3. Oral Swellings: Single & Multiple 4. Radiolucent Jaw Lesions: From Benign to Metastatic 5. Radiopaque Jaw Lesions: Benign & Other Oral SCC: Tobacco-Associated White lesions 1. Frictional white patches a. Tongue chewing b. Others 2. Contact white patches 3. Smoker’s white patches a. Smokeless tobacco b. Cigarette smoking 4. Idiopathic white patches Red, Speckled lesions 5. Erythroplakia 6. Georgraphic tongue 7. Median rhomboid glossitis Deep Single ulcers 8. Traumatic ulcer -TUGSE 9. Infectious Disease 10. Necrotizing sialometaplasia Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Tobacco-associated If you suspect that a lesion is malignant, refer to an oral surgeon for a biopsy. It is the most common type of oral SCC, which accounts for over 75% of all malignant neoplasms of the oral cavity. Clinically, it is more common in men over 55 years of age, heavy smokers and heavy drinkers, more in males especially black males. However, it has been described in young white males, under the age of fifty non-smokers and non-drinkers. The latter group constitutes less than 5% of the patients and their SCCs tend to be in the posterior mouth (oropharynx and tosillar area) associated with HPV infection especially HPV type 16. The most common sites for the tobacco-associated are the lateral and ventral tongue, followed by the floor of mouth and soft palate area. -

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition Category ABNORMALITIES OF TEETH 426390 Subcategory Cementum Defect 399115 Cementum aplasia 346218 Absence or paucity of cellular cementum (seen in hypophosphatasia) Cementum hypoplasia 180000 Hypocementosis Disturbance in structure of cementum, often seen in Juvenile periodontitis Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia 958771 Familial multiple cementoma; Florid osseous dysplasia Diffuse, multifocal cementosseous dysplasia Hypercementosis (Cementation 901056 Cementation hyperplasia; Cementosis; Cementum An idiopathic, non-neoplastic condition characterized by the excessive hyperplasia) hyperplasia buildup of normal cementum (calcified tissue) on the roots of one or more teeth Hypophosphatasia 976620 Hypophosphatasia mild; Phosphoethanol-aminuria Cementum defect; Autosomal recessive hereditary disease characterized by deficiency of alkaline phosphatase Odontohypophosphatasia 976622 Hypophosphatasia in which dental findings are the predominant manifestations of the disease Pulp sclerosis 179199 Dentin sclerosis Dentinal reaction to aging OR mild irritation Subcategory Dentin Defect 515523 Dentinogenesis imperfecta (Shell Teeth) 856459 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield I 977473 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield II 976722 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; -

2015 Posters

AAOMP Poster Abstracts #2 CONGENITAL GRANULAR CELL LESION IN THE VENTRAL TONGUE IN A 2 DAY-OLD NEWBORN B. Aldape, México city, A. Andrade, Mexico city A 2 day old newborn healthy girl from Cancun, Quintana Roo, with a polypoid mass in the ventral tongue near the Blandin Nun salivary glands, this is the first case in the family with this pathology. The mass is peduculated, exophytic, smooth, soft and the same color of the mucosa, measuring 8 x 6 x 4 mm., and the clinical diagnosis was mucocele versus hamartomas or coristoma. The excisional biopsy was made under local anesthesia, not complications were present during the surgical removal. Microscopically stained with H&E the lesion was composed of large cell containing abundant granular cytoplasm and small hyperchromatic nuclei. The immmunohistochemical was positive for vimetine, but negative for S-100 protein, alfa-smooth muscle actin an CD68. The diagnosis was CONGENITAL GRANULAR CELL LESION (Histological classification by the WHO) because the origin is the soft tissues and not in the alveolar regions, there are only 10 cases reported in the literature, the first was diagnosed in 1975 Dixter CT. #4 A CASE OF IN SITU CARCINOMA CUNICULATUM F.Samim, UBC (U of British Columbia) , Vancouver,BC CA, C.Poh, UBC, Vancouver BC Oral Carcinoma Cuniculatum (CC) is a distinct entity with the potential for local aggressiveness. Although CC was included in the 2005 World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumors, its clinicopathologic features remain to be fully addressed. Clinical and histologic diagnosis can be challenging, as CC may mimic reactive or benign lesions, especially at its early stage. -

1. Drugs That May Prove Useful for Treatment of Mucositis in Patients

Mock Academic Fellowship Examination American Academy of Oral Medicine THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ORAL MEDICINE INCORPORATED UNDER THE LAWS OF NEW YORK STATE (Founded 1945) 1. Drugs that may prove useful for treatment of mucositis in patients undergoing head and neck radiation therapy are: A) Chlorhexidine B) Amifostine C) Pilocarpine hydrochloride D) B and C E) None of the above 2. Post radiation osteonecrosis of the jaws can be characterized as tissues which are: A) Hypervascular B) Hypocellular C) Hyponatremic C) Hyperosmotic 3. Topical agents that may be useful in patients who develop oral mucositis secondary to head and neck radiation are: A) Topical doxepin B) Topical Morphine C) Topical benzydamine D) All of the above 4. The most common benign tumor of salivary glands is: A) Oncocytoma B) Basal cell adenoma C) Monomorphic adenoma D) Pleomorphic adenoma 5. The most common sustained cardiac dysrhymia is: A) Premature ventricular contraction B) Wolff-Parkinson White Syndrome C) Supraventricular tachycardia D) Atrial fibrillation 1 Mock Academic Fellowship Examination 6. The ideal time to provide elective dental treatment for patients who are receiving renal dialysis is: A) Immediately following dialysis B) The day of dialysis C) On a non-dialysis day as early as possible from the next dialysis treatment D) Just before dialysis E) Anytime after awakening 7. A patient presents for extraction of 3 carious teeth. Past medical history includes chronic renal failure, hemodialysis, insulin dependent diabetes mellitus and total knee replacement. Appropriate dental care would include: A) Recording vital signs prior to treatment B) Use of adjunctive hemostatic agents at the time of surgery C) Pre-operative antibiotic consideration D) All of the above 8. -

Traumatic Bone Cyst of the Jaws: a Report of Two Cases and Review 1Pradeesh Sathyan, 2T Isaac Joseph, 3George Jacob

OMPJ Traumatic Bone Cyst of the Jaws:10.5005/jp-journals-10037-1044 A Report of Two Cases and Review CASE REpoRT Traumatic Bone Cyst of the Jaws: A Report of Two Cases and Review 1Pradeesh Sathyan, 2T Isaac Joseph, 3George Jacob ABSTRACT Pain is the presenting symptom in 10 to 30% of the 3-5 Traumatic bone cyst (TBC) is an uncommon disorder of the jaw patients. Other, more unusual symptoms include bones, as well as other skeletal bones, particularly the long bones. tooth sensitivity, paresthesia, fistulas, delayed eruption Traumatic bone cyst is an asymptomatic, slow gro wing lesion com- of permanent teeth, displacement of the inferior dental monly diagnosed incidentally during routine radiographic exami - 6-10 nation of the jaw bones. Of the jaw bones, mandible is affected canal and pathologic fracture of the mandible. The much more than the maxilla. The etiology is unclear and trauma WHO classification of Head and Neck Tumours, 2005 cannot be definitely determined to be the cause. Surgical explo- describes TBC as a nonneoplastic osseous lesion because ration of the cavity is curative in most cases and do not require it shows no epithelial lining, which differentiates this any other treatment. We present two well documented, radio- 11 graphically and histopathologically confirmed cases of TBC lesion from the true cysts of age. Radiographically, it involving the jaw bones. Based on the literature available, the manifests as a well defined,unilocular, radiolucent area etiopathogenesis, treatment, asso ciations and possible compli- which occasionally presents a typical festooned pattern cations of this disorder have been discussed. -

DH 318 General and Oral Pathology

DH 248 General and Oral Pathology Spring 2014 Meeting Times: Tuesday & Thursday 10:00 - 11:50 a.m. CASA Mortuary Science Room 70 Credits: 4 credit hours Faculty: Sherri Lukes, RDH, MS, Associate Professor, Room 129 Office: 453-7289 Cell: 521-3392 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Monday 1:00 p.m. - 4:00 p.m. Tuesday 1:00-4:00 Other office hours by appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course has been designed to integrate oral pathology and general pathology. Students will study principles of general pathology with emphasis on the relationships to oral diseases. Pathologic physiology is included such as tissue regeneration, the inflammatory process, immunology and wound healing. Clinical appearance, etiology, location and treatment options of general system diseases is presented, along with the oral manifestations. Special attention will be placed on common pathological conditions of the oral cavity and early recognition of these conditions. DH Competencies addressed in the course: PC.1 Systematically collect analyze, and record data on the general, oral, and psychosocial health status of a variety of patients/clients using methods consistent with medico-legal principles. PC.2 Use critical decision making skills to reach conclusions about the patient’s/client’s dental hygiene needs based on all available assessment data. PC.3 Collaborate with the patient / client, and/or other health professionals, to formulate a com- prehensive dental hygiene care plan that is patient / client-centered and based on current scientific evidence. PC.4 Provide specialized treatment that includes preventive and therapeutic services designed to achieve and maintain oral health. Assist in achieving oral health goals formulated in collaboration with the patient / client. -

Orthokeratinised Odontogenic Cyst: a Diagnostic Havoc

J Dent Res Prac 2019; 1(1): 18-22. Orthokeratinised Odontogenic Cyst: A Diagnostic Havoc Balamurugan R*, Sahana PT Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, RYA Cosmo Foundation Hospital, Chennai, India *Correspondence should be addressed to Balamurugan R, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, RYA Cosmo Foundation Hospital, Chennai, India; Tel: 9941259243; E-mail: [email protected] Received: 7 Aug 2019 • Accepted: 17 Aug 2019 ABSTRACT This case report presents a 27 year old male patient who reported with pain in his anterior mandible since a week. History revealed an incidence of trauma on his chin when he was young for which he didn't undergo any treatment. On examination buccal cortical expansion was clinically evident and tenderness was elicited on percussing over the lower anterior teeth. Aspiration was negative initially while it showed serous blood the second time. Radiograph featured an unilocular radiolucency extending from distal of left mandibular first premolar to mesial of right mandibular first molar with an impacted right mandibular canine was seen. Displacement of teeth and inter-radicular scalloping were also evident. With all these clinical and radiographic features we could arrive at a provisional diagnosis of odontogenic keratocyst. A differential diagnosis of traumatic bone cyst and ameloblastoma were also considered. A Complete surgical excision with curettage of the cystic cavity was performed following which histopathological evaluation confirmed the lesion to be an orthokeratinised odontogenic cyst. Keywords: Diagnostic challenges, Odontogenic keratocyst, Orthokeratinised odontogenic cyst. Copyright ©2019 Balamurugan R et al. This is an open access paper distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License. Journal of Dental Research and Practice is published by Lexis Publisher INTRODUCTION Orthokeratinised odontogenic cyst is a rare phenomenon of developmental odotogenic cyst first described by Wright in 1981 with incidence of 7%-17%.