The Struggle for Energy Democracy in the Maghreb Hamza Hamouchene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Market Analysis for Gas Engine Technology in Algeria

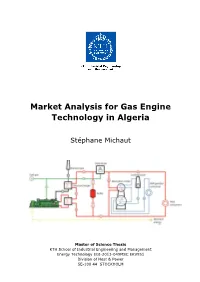

Market Analysis for Gas Engine Technology in Algeria Stéphane Michaut Master of Science Thesis KTH School of Industrial Engineering and Management Energy Technology EGI-2013-049MSC EKV951 Division of Heat & Power SE-100 44 STOCKHOLM Master of Science Thesis EGI-2013-049MSC EKV951 MARKET ANALYSIS FOR GAS ENGINE TECHNOLOGY IN ALGERIA Stéphane Michaut Approved Examiner Supervisor at KTH 2013-06-04 Prof. Torsten Fransson Miroslav Petrov Commissioner Contact person at industry CLARKE ENERGY Ltd., Algeria Didier Lartigue Abstract The objective of this diploma thesis is to investigate the potential of combined heat and power plants based on gas engine technology in Algeria. This market analysis has been performed in order to identify the key markets for the newly created French subsidiary of Clarke Energy Group to expand its business in North Africa. After analyzing the structure of the Algerian energy sector and the potential of each gas engine application, three key sectors were identified. For each sector, a technical and economical analysis was conducted in order to define its potential, its constraints, and the time frame under which they could become mature markets. With a potential of 300 MW, the first targeted sector is related to the national power utility Sonelgaz and consists in small scale power plants with a nominal power output < 20 MW, in which the use of gas engines instead of gas turbines could reduce up to 50% the price of kWh generated over the lifecycle of the plant. With a total of 450 MW, the second market representing a great potential for gas engines development in Algeria is the industrial sector and in particular brick factories, in which cogeneration plants become profitable within 4 years, can save up to 40% of primary energy and generate electricity whose cost of production is 30% lower than the average grid price. -

Regional Energy Integration in Africa

Regional Energy Integration In Africa A Report of the World Energy Council June 2005 World Energy Council Regional Energy Integration in Africa Regional Energy Integration in Africa Copyright © 2005 World Energy Council All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, electrostatic, magnetic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright holder. Published June 2005 by: World Energy Council 5th Floor, Regency House 1-4 Warwick Street London W1B 5LT United Kingdom www.worldenergy.org ISBN 0-946121-20-6 2 World Energy Council Regional Energy Integration in Africa Officers of the World Energy Council André Caillé Pierre Gadonneix Chair World Energy Council Vice Chair Europe Majid Al-Moneef C.P Jain Vice Chair Special Responsibility Chair Studies Committee Gulf States & Central Asia Francisco Barnés de Castro Shige-etsu Miyahara Vice Chair North America Vice Chair Asia Asger Bundgaard-Jensen Chicco Testa Vice Chair Finance Vice Chair Rome 2007 Norberto de Franco Medeiros Ron Wood Vice Chair Latin America/Caribbean Chair Programme Committee Alioune Fall Gerald Doucet Vice Chair Africa Secretary General Member Committees of the World Energy Council Algeria Hungary Peru Argentina Iceland Philippines Australia India Poland Austria Indonesia Portugal Bangladesh Iran (Islamic Rep.) Qatar Belarus Ireland Romania Belgium Israel Russian Federation Bolivia Italy Saudi Arabia Botswana Japan Senegal Brazil Jordan -

Whose Sustainability? Political Economy of Renewable Energy Transitions in Morocco and Algeria

Whose Sustainability? Political Economy of renewable energy transitions in Morocco and Algeria Adela Syslová Student ID: 677078 MSc Development Studies This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MSc Development Studies of SOAS, University of London. 07/09/2020 Word count: 10,243 I have read and understood the School Regulations concerning plagiarism and I undertake: • That all material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part by any other person(s). • That any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the dissertation • That I have not incorporated in this dissertation without acknowledgement any work previously submitted by me for any other module forming part of my degree. I give permission for a copy of my dissertation to be held for reference, at the School's discretion. Signed Adela Syslová Table of Contents Abstract 2 Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 5 Theories of transition 9 Energy dynamics in the Middle East and North Africa 13 Algeria's struggled path away from fossil fuels 16 Algeria's efforts for renewable energy 16 The issue of natural gas 17 Energy efficiency and subsidies 19 Corruption and rent-seeking 20 Morocco: A story of success 22 Adopting efficient policies to foster renewables 23 Elements of the Moroccan vision for sustainable development 24 Facilitating technology transfer 26 Mediterrean interrelationality and demand-induced obstacles 28 Discussion: Extended dimensions of lock-in 30 Morocco's locked-in future 30 Algeria and global energy: Limited opportunities for change 32 Natural gas as a bridge fuel 33 Conclusion: Looking into the future 35 Bibliography 37 Adela Syslová - 677078 1 Abstract The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has one of the highest potentials for renewable energy in the world, yet this potential remains poorly exploited. -

L'algérie 100%

STUDY The energy transition to CLIMATE CHANGE, ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT renewable sources responds to various objectives, consi dering the economic dimen sion, energy efficiency, and ALGERIA 100% ecological responsibility. RENEWABLE In addition to solving the crucial problem of energy availability at an acceptable ENERGY cost, developing renewables is a safer economic growth potential for Algeria, which Recommendations for a National Strategy will thus emerge from its de of Energy Transition pendence on hydrocarbons. Tewfik Hasni, Redouane Malek The switch to this new model and Nazim Zouioueche of energy production will January 2021 reduce pollution, thus con tributing to the global chal lenge of the fight against global warming. CLIMATE CHANGE, ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT ALGERIA 100% RENEWABLE ENERGY Recommendations for a National Strategy of Energy Transition Content 1 INTRODUCTION 4 2 SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS 5 3 WHY AIM FOR 100% RENEWABLE ENERGY IN ALGERIA? 6 4 RENEWABLE ENERGIES IN ALGERIA 9 5 OBSTACLES TO ESTABLISHING 100% RENEWABLE ENERGY IN ALGERIA 11 6 EMBEDDING THE 100% RENEWABLE ENERGY STRATEGY IN THE NATIONAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PLAN 12 7 CONCLUSION 22 Annex 1 : Texts on energy control ����������������������������������������������������������������������� 24 Annex 2 : Additional sources of information ����������������������������������������������������� 26 Bibliography �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 26 Abreviations ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������27 -

ASG Analysis: What Makes Algeria’S New Solar Tender Different? May 28, 2021

ASG Analysis: What Makes Algeria’s New Solar Tender Different? May 28, 2021 In April, Algeria announced plans to launch a tender this summer for a gigawatt (GW) of photovoltaic solar power production. Solar project announcements in Algeria have a spotty record – a 4GW tender announced in 2017 never materialized, a 1GW project assigned to the national hydrocarbons company has seen limited progress, and an attempt to tender 150 megawatts (MW) of solar energy locally did not successfully award all lots. Investors are asking: What might be different this time? If this time is the real deal, investors do not want to be late to the party. Algeria is the largest country in Africa, by geography. It has massive solar If this time is the real potential, sharply rising energy demand, and one of the highest per-capita deal, investors do not gross domestic product (GDP) levels on the continent. Algerian officials often want to be late to the spend significant time vetting potential partners up front, but once they make party. a choice, they tend to stick with it. There are several points that firms hoping to capitalize on this opportunity and others in Algeria should keep in mind. First – foreign companies can now hold majority ownership in these projects, which is a game-changer. Many international businesses had identified Algeria’s so-called “51/49 rule” (which required majority Algerian ownership of any business venture) as a stumbling block for international investment. While 51/49 still applies to “strategic sectors” such as hydrocarbons and mining, the government has declared renewable energy investment free from such restrictions. -

Accelerating Energy Efficiency: Initiatives and Opportunities Africa

ERGY EFFICIENCY: INITIATIVES AND OPPORTUNITIES AFRICA. ACCELERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY: INITIATIVES AND OPPORTUNITIES AFRICA. ACCELERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY: INITIATIVES OPPORTUNITIES AFRICA. ACCELERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY: INITIATIVES AND OPPORTUNITIES AFRICA. ACCELERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY: INITIATIVES AND OPPORTUNITIES AFRICA. AC LERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY: INITIATIVES AND OPPORTUNITIES AFRICA. ACCELERATING ENERGY EFFICI LERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY: I IENCY: INITIATIVES AND OPPORTUNITIES AFRICA. ACCELERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY: INITIATIVES AND ACCELERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY: NIT ATIVES AND OPPORT RICA. ACCELERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY: INITIATIVES AND OPPORTUNITIES AFRICA. ACCELERATING ENINITIATIVES AND OPPORTUNITIES AFRICA CELERATING ENRGY EFFI NCY: INITIATIVES AND OPPORTUNITIES AFRICA. ACCELERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY:CIENCY: INITIATIVES AND OPPORTUNITIES AFRICA. ACCELERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY: INITIATIVES AND OPPORTU IES AFRICA. ACCELERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY: INITIATIVES AND OPPORTUNITIESNITIES AFRICA. ACCELERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY: INITIATIVES AND OPPORTUNITIES AFRICA. ACCELERATING ERGY EFFICIENCY: INITIATIVES AND OPPORTUNITIES AFRICA. ACCELERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY: INITIATIVES AND AFRICA. ACCELERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY: INITIATIVES D OPPORTUNITIES AFRICA. ACCELERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY: INITIATIVES AND OPPORTUNITIES AFRICA. ACCELENERGY EFFICIENCY: INITIATIVES AND OPPORTUNITIES AFRICA. AC LERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY: INITIATIVES AND OPPORTUNITIES AFRICA. ACCELERATINGCELERATING ENERGY EFFICIENCY: A ORTUNITI OPPORT A. -

Starting a New Chapter in Eu-Algeria Energy Relations

POLICY PAPER 173 30 SEPTEMBER 2016 STARTING A NEW CHAPTER IN EU-ALGERIA ENERGY RELATIONS A PROPOSAL FOR A TARGETED COOPERATION Jekaterina Grigorjeva | Affiliate fellow at the Jacques Delors Institut – Berlin EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This policy paper calls for a more prominent position of Algerian energy and its potential impact on the resil- ience of the Southern Mediterranean region on the EU agenda. Thereby it suggests the establishment of a tar- geted energy cooperation aimed at switching Algerian domestic consumption to renewable energy as a poten- tial way of addressing the encountered policy challenges. Algeria – the State of Affairs The analysis of the current situation in Algeria points towards a threat of economic and potentially also politi- cal destabilization of the country. Due to the high dependency of Algerian economy on the hydrocarbons’ reve- nues this can be at least partly attributed to the critical developments in the energy sector. In particular, rising domestic energy demand and falling natural gas exports decrease the revenues available to the government to buy its way out of political turmoil. The huge renewable energy potential, which could sustainably solve the problem of an ever rising domestic consumption, remains untapped. If not addressed, the critical developments in Algeria are likely to have a direct impact on the EU: the security of gas supplies, the resilience of the EU’s Southern neighbourhood, and potentially also the EU’s own security. Targeted Energy Cooperation: Switching Domestic Consumption to Renewable Energy The EU could play a positive role by supporting Algeria in building its THE EU COULD PLAY own energy transition aimed at switching domestic consumption, first partly and prospectively fully, to renewable energy. -

Estimation of Hydrogen Production Using Wind Energy in Algeria

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Energy Procedia 74 ( 2015 ) 981 – 990 International Conference on Technologies and Materials for Renewable Energy, Environment and Sustainability, TMREES15 Estimation of hydrogen production using wind energy in Algeria Mohamed Douaka,*, Noureddine Settoub aUniv Kasdi Merbah-Ouargla,Department of petroleum production, Ouargla 30 000, Algeria bUniv Kasdi Merbah-Ouargla, Department of mechanics, Ouargla 30 000, Algeria Abstract In response to problems involved in the current crisis of petrol in Algeria, with the decrease in the price of the oil barrel, the rate of growth in domestic electricity demand and with an associated acceleration of global warming, as a result of significantly increased greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, renewable energy seems today as a clean and strategic substitution for the next decades. However, the greatest obstacles which face electric energy comes from renewable energy systems are often referred to the intermittency of these sources as well as storage and transport problems, the need for their conversion into a versatile energy carrier in its use, storable, transportable and environmentally acceptable are required. Among all the candidates answering these criteria, hydrogen presents the best answer. In the present work, particular attention is paid to the production of hydrogen from wind energy. The new wind map of Algeria shows that the highest potential wind power was found in Adrar, Hassi-R'Mel and Tindouf regions. The data obtained from these locations have been analyzed using Weibull probability distribution function. The wind energy produced in these locations is exploited for hydrogen production through water electrolysis. The objective of this paper is to realize a technological platform allowing the evaluation of emergent technologies of hydrogen production from wind energy using four wind energy conversion systems of 600, 1250, 1500 and 2000 kW rated capacity. -

Current Status, Scenario, and Prospective of Renewable Energy in Algeria: a Review

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 9 March 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202103.0260.v1 Type of the Paper (Article, Review, Communication, etc.) Current Status, Scenario, and Prospective of Renewable Energy in Algeria: A Review Younes Zahraoui 1*, M. Reyasudin Basir Khan 2, Ibrahim Al Hamrouni 1 , Saad Mekhilef 3 , and Mahrous Ahmed 4, 1 Universiti Kuala Lumpur, British Malaysian Institute, Bt. 8, Jalan Sungai Pusu, 53100 Gombak, Selangor, Malaysia. 2 Manipal International University, No. 1, Persiaran MIU, 71800 Putra Nilai, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. 3 Power Electronics and Renewable Energy Research, Laboratory, Department of Electrical Engineering, Uni- versity of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur 50603, Malaysia. 4 Electrical Engineering Department, College of Engineering, Taif University, Taif 21944, Saudi Arabia.. * Correspondence: [email protected], [email protected]. Abstract: Energy demand has been overgrowing in developing countries. Moreover, the fluctua- tion of fuel prices is a primary concern faced by many countries that highly rely on conventional power generation to meet the load demand. Hence, the need to use alternative resources such as renewable energy is crucial to mitigate fossil fuel dependency alongside the reduction of Carbon Dioxide emission. Algeria’s being the largest county in Africa has rapid growth in energy demand since the past decade due to the significant increase of residential, commercial, and industry sectors. Currently, the hydrocarbon-rich nation highly dependent on fossil fuels for electricity generation, where renewable energy only has a small contribution to the country’s energy mix. However, the country has massive potential for renewable energy generations such as solar, wind, biomass, geo- thermal, and hydropower. -

Current Status, Scenario, and Prospective of Renewable Energy in Algeria: a Review

energies Review Current Status, Scenario, and Prospective of Renewable Energy in Algeria: A Review Younes Zahraoui 1,* , M. Reyasudin Basir Khan 2 , Ibrahim AlHamrouni 1, Saad Mekhilef 3,4,5 and Mahrous Ahmed 6 1 British Malaysian Institute, Universiti Kuala Lumpur, Bt. 8, Jalan Sungai Pusu, Selangor 53100, Malaysia; [email protected] 2 School of Engineering, Manipal International University, No. 1, Persiaran MIU, Putra Nilai 71800, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia; [email protected] 3 Power Electronics and Renewable Energy Research, Laboratory, Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur 50603, Malaysia; [email protected] 4 School of Software and Electrical Engineering, Faculty of Science, Engineering and Technology, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne, VIC 3122, Australia 5 Center of Research Excellence in Renewable Energy and Power Systems, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah 21589, Saudi Arabia 6 Electrical Engineering Department, College of Engineering, Taif University, Taif 21944, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] Abstract: Energy demand has been overgrowing in developing countries. Moreover, the fluctuation of fuel prices is a primary concern faced by many countries that highly rely on conventional power generation to meet the load demand. Hence, the need to use alternative resources, such as renewable energy, is crucial in order to mitigate fossil fuel dependency, while ensuring reductions in carbon dioxide emissions. Algeria—being the largest county in Africa—has experienced a rapid growth Citation: Zahraoui, Y.; Basir Khan, in energy demand over the past decade due to the significant increase in residential, commercial, M.R.; AlHamrouni, I.; Mekhilef, S.; and industry sectors. -

Sonatrach Solar Power Development Program

Sonatrach Solar Power Development Program Houston, TX – March7, 2019 0 Agenda v Algeria’s Advantages in Solar Energy v National Renewable Energy Development Strategy v Sonatrach 2030 Vision v Solar Power Plants Program v Sonatrach and Partnership v Pilot Project - BRN, Main Information v PV Implementation as a Solution v Sonatrach's Role in the Development of Solar Energy in Algeria v Conclusion 13/03/2019 1 Algeria's Advantages in Solar Energy v An annual average irradiation of ~ 2,000 kWh / m2 v Availability of large spaces (South and Highlands) v Significant coverage of the national electricity grid v An existing photovoltaic installed capacity of ~ 350 MW v Local industry, know-how and expertise at the national level 2 National Renewable Energy Development Strategy v The National Renewable Energy Program considered as a National Priority v The National Program for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency : Deployment of 22 GW capacity including 13.5 GW of solar energy by 2030 v Sonatrach’s vision SH2030 fits fully into the national strategy of the development of renewable energy 3 Sonatrach 2030 Vision 4 Solar Power Plants Development Program National Renewable Solar projects in progress & in development Energy Program 344 Sonelgaz power plants (SKTM) in operation MW • 23 PV plants in the Highlands and the South Calls for tenders from the CREG 150 • 7 power stations PV in the south of the country MW • Call for tender launched end of 2018 13.5 GW Solar energy 50 Sonelgaz projects MW • Hybridization of diesel plants with PV in 2030 1000 Sonatrach Program - Connected to the electricity grid MW • Achievement target by 2020 1300 Sonatrach Program on its industrial sites MW • Achievement target by 2030 5 Sonatrach and Partnership SONATRACH is engaged in energy transition by actively solarizing its facilities to cover 80% of site needs à Up to 1.3 GW solar power to supply all eligible sites. -

Renewable Energy

NATURAL RESOURCES Algeria has considerable and diversified natural resources, particularly hydrocarbons. It ranks 16th in oil reserves, 16th in production (2019) and 11th in exports (2019). Algeria ranks 10th in the world regarding proven gas resources (2020), 10th in gas production (2020) and 7th in gas exports. Algeria is the third largest supplier of natural gas to the European Union and its fourth largest energy supplier. Besides oil and gas, its underground contains large deposits of phosphate, zinc, iron, gold, uranium, tungsten... etc. It has also renewable natural resources and is one of the best endowed countries in the world with solar resources. Integrating renewable energy into the national energy mix is a major challenge for preserving fossil resources, diversifying electricity production lines, and contributing to sustainable development and environmental protection. Through the 2011- 2030 renewable energy development program mentioned above, these energies are at the heart of Algeria’s energy and economic policies, including the development of large-scale photovoltaic and wind energy, the introduction of biomass (waste recovery), cogeneration and geothermal energy, and eventually the development of solar thermal energy. RENEWABLE ENERGY: Algeria is starting a green energy dynamic by launching an ambitious program of renewable energy development and energy efficiency. The Algerian government’s strategy focuses on the development of inexhaustible resources such as solar energy and their use to diversify energy sources and prepare Algeria for the future. By combining initiatives and intelligence, Algeria is committed to a new and sustainable energy era. According to Ministry of Energy Transition and Renewable Energy, the multi-annual program for the development of renewable energy and energy efficiency, adopted by the Government in February 2020, sets a target of 15,000 MW by 2035.