Maldives Country Report Impact of the Tsunami Response on Local And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electricity Needs Assessment

Electricity needs Assessment Atoll (after) Island boxes details Remarks Remarks Gen sets Gen Gen set 2 Gen electricity electricity June 2004) June Oil Storage Power House Availability of cable (before) cable Availability of damage details No. of damaged Distribution box distribution boxes No. of Distribution Gen set 1 capacity Gen Gen set 1 capacity Gen set 2 capacity Gen set 3 capacity Gen set 4 capacity Gen set 5 capacity Gen Gen set 2 capacity set 2 capacity Gen set 3 capacity Gen set 4 capacity Gen set 5 capacity Gen Total no. of houses Number of Gen sets Gen of Number electric cable (after) cable electric No. of Panel Boards Number of DamagedNumber Status of the electric the of Status Panel Board damage Degree of Damage to Degree of Damage to Degree of Damaged to Population (Register'd electricity to the island the to electricity island the to electricity Period of availability of Period of availability of HA Fillladhoo 921 141 R Kandholhudhoo 3,664 538 M Naalaafushi 465 77 M Kolhufushi 1,232 168 M Madifushi 204 39 M Muli 764 134 2 56 80 0001Temporary using 32 15 Temporary Full Full N/A Cables of street 24hrs 24hrs Around 20 feet of No High duty equipment cannot be used because 2 the board after using the lights were the wall have generators are working out of 4. reparing. damaged damaged (2000 been collapsed boxes after feet of 44 reparing. cables,1000 feet of 29 cables) Dh Gemendhoo 500 82 Dh Rinbudhoo 710 116 Th Vilufushi 1,882 227 Th Madifushi 1,017 177 L Mundoo 769 98 L Dhabidhoo 856 130 L Kalhaidhoo 680 94 Sh Maroshi 834 166 Sh Komandoo 1,611 306 N Maafaru 991 150 Lh NAIFARU 4,430 730 0 000007N/A 60 - N/A Full Full No No 24hrs 24hrs No No K Guraidhoo 1,450 262 K Huraa 708 156 AA Mathiveri 73 2 48KW 48KW 0002 48KW 48KW 00013 breaker, 2 ploes 27 2 some of the Full Full W/C 1797 Feet 24hrs 18hrs Colappes of the No Power house, building intact, only 80KW generator set of 63A was Distribution south east wall of working. -

Population and Housing Census 2014

MALDIVES POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS 2014 National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’, Maldives 4 Population & Households: CENSUS 2014 © National Bureau of Statistics, 2015 Maldives - Population and Housing Census 2014 All rights of this work are reserved. No part may be printed or published without prior written permission from the publisher. Short excerpts from the publication may be reproduced for the purpose of research or review provided due acknowledgment is made. Published by: National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’ 20379 Republic of Maldives Tel: 334 9 200 / 33 9 473 / 334 9 474 Fax: 332 7 351 e-mail: [email protected] www.statisticsmaldives.gov.mv Cover and Layout design by: Aminath Mushfiqa Ibrahim Cover Photo Credits: UNFPA MALDIVES Printed by: National Bureau of Statistics Male’, Republic of Maldives National Bureau of Statistics 5 FOREWORD The Population and Housing Census of Maldives is the largest national statistical exercise and provide the most comprehensive source of information on population and households. Maldives has been conducting censuses since 1911 with the first modern census conducted in 1977. Censuses were conducted every five years since between 1985 and 2000. The 2005 census was delayed to 2006 due to tsunami of 2004, leaving a gap of 8 years between the last two censuses. The 2014 marks the 29th census conducted in the Maldives. Census provides a benchmark data for all demographic, economic and social statistics in the country to the smallest geographic level. Such information is vital for planning and evidence based decision-making. Census also provides a rich source of data for monitoring national and international development goals and initiatives. -

Kudahuvadhoo and Nilandhoo Collection Centers Have Been Officially Opened 3

Maldives Inland Revenue Authority Volume: 5 MIRAmaldives Number: 11 Mira Maldives November 2017 MIRAPost miramaldives Kudahuvadhoo and Nilandhoo MIRAcollection collects centers a record have MVR been 2.2 billion officially2 opened u3 MIRA’s teams to visit atolls to assist If annual income is over MVR 20 million, taxpayers in preparing financial statements GST returns must be filed online 11 and BPT Return 3 Additional leeway given over GST charged MIRA warns over non-licensed tax agents on complementary bills u2 u6 2 MIRAPost November 2017 MIRA October collection totals to 983.5 million Mariyam Juwairiyya date for payment of this fee was during October. Senior Tax Officer, Policy, Planning and Statistics Including the revenue of October, MIRA’s revenue collections add up to an aggregate of MVR 12.89 During October 2017, MIRA collected MVR billion so far. 983.5 million, including 38.1 million in US dollar. Other revenue types that contributed a This is a 10.7% rise compared to that of October significant share in October’s collection includes 2016 and a 4% rise in the expected revenue. GST (MVR 539.6 million), BPT (MVR 78.5 This increase was mainly contributed by Tourism million), Green Tax (MVR 53.9 million) and Land Rent (MVR 128.5 million), as the due Airport Service Charge (MVR 45.5 million). Additional leeway given over GST charged on complementary bills services provided free of charge to directors, employees Fathimath Amaanee Khalid and related parties, as specified under section 54 of Senior Tax Officer, Policy, Technical Service the GST Regulation, are not subject to GST for a period of 72 hours. -

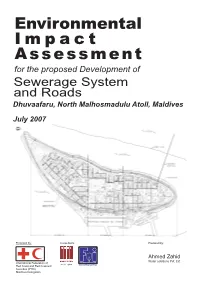

Environmental Impact Assessment for the Proposed Development Of

Environmental Impact..... Assessment for the proposed Development of Sewerage System and Roads Dhuvaafaru, North Malhosmadulu Atoll, Maldives July 2007 Proposed by: Consultants Prepared by: Ahmed Zahid Water solutions Pvt. Ltd. International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) Maldives Delegation EIA for the development of Proposed Road and Sewerage System on R. Dhuvaafaru i Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................................... I LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................................................................. I LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................................ I LIST OF PLATES ................................................................................................................................................ I DECLARATION OF THE CONSULTANT ..................................................................................................... II NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... III 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... -

Table 2.3 : POPULATION by SEX and LOCALITY, 1985, 1990, 1995

Table 2.3 : POPULATION BY SEX AND LOCALITY, 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000 , 2006 AND 2014 1985 1990 1995 2000 2006 20144_/ Locality Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Both Sexes Males Females Republic 180,088 93,482 86,606 213,215 109,336 103,879 244,814 124,622 120,192 270,101 137,200 132,901 298,968 151,459 147,509 324,920 158,842 166,078 Male' 45,874 25,897 19,977 55,130 30,150 24,980 62,519 33,506 29,013 74,069 38,559 35,510 103,693 51,992 51,701 129,381 64,443 64,938 Atolls 134,214 67,585 66,629 158,085 79,186 78,899 182,295 91,116 91,179 196,032 98,641 97,391 195,275 99,467 95,808 195,539 94,399 101,140 North Thiladhunmathi (HA) 9,899 4,759 5,140 12,031 5,773 6,258 13,676 6,525 7,151 14,161 6,637 7,524 13,495 6,311 7,184 12,939 5,876 7,063 Thuraakunu 360 185 175 425 230 195 449 220 229 412 190 222 347 150 197 393 181 212 Uligamu 236 127 109 281 143 138 379 214 165 326 156 170 267 119 148 367 170 197 Berinmadhoo 103 52 51 108 45 63 146 84 62 124 55 69 0 0 0 - - - Hathifushi 141 73 68 176 89 87 199 100 99 150 74 76 101 53 48 - - - Mulhadhoo 205 107 98 250 134 116 303 151 152 264 112 152 172 84 88 220 102 118 Hoarafushi 1,650 814 836 1,995 984 1,011 2,098 1,005 1,093 2,221 1,044 1,177 2,204 1,051 1,153 1,726 814 912 Ihavandhoo 1,181 582 599 1,540 762 778 1,860 913 947 2,062 965 1,097 2,447 1,209 1,238 2,461 1,181 1,280 Kelaa 920 440 480 1,094 548 546 1,225 590 635 1,196 583 613 1,200 527 673 1,037 454 583 Vashafaru 365 186 179 410 181 229 477 205 272 -

0 NATIONAL TENDER AWARDED PROJECTS Project Number Agency Project Name Island Awarded Party Awarded Amount in MVR Contract Durati

0 as of 09th January 2020 National Tender Ministry of Finance NATIONAL TENDER AWARDED PROJECTS Project Number Agency Project Name Island Awarded Party Awarded Amount in MVR Contract Duration Assembling of Kalhuvakaru Mosque and Completion of Landscape TES/2019/W-054 Completion of Landscape works AMAN Maldives Pvt Ltd MVR 2,967,867.86 120 Days Department of Heritage works TES/2019/W-103 Local Government Authority Construction of L. Isdhoo Council new Building L. Isdhoo UNI Engineering Pvt Ltd MVR 4,531,715.86 285 Days TES/2019/W-114 Local Government Authority Construction of Community Centre - Sh. Foakaidhoo Sh. Foakaidhoo L.F Construction Pvt Ltd MVR 5,219,890.50 365 Days TES/2019/W-108 Local Government Authority Construction of Council New Building at Ga. Kondey Ga. Kondey A Man Maldives pvt Ltd MVR 4,492,486.00 365 Days TES/2019/W-117 Local Government Authority Construction of Council Building at K.Hura K.Hura Afami Maldives Pvt Ltd MVR 5,176,923.60 300 Days TES/2019/W-116 Local Government Authority Construction of Council Building at Th. Madifushi Th. Madifushi Afami Maldives Pvt Ltd MVR 5,184,873.60 300 Days TES/2019/W-115 Local Government Authority Construction of Council Building at Lh.Naifaru Lh.Naifaru Nasa Link Pvt Ltd MVR 5,867,451.48 360 Days Safari Uniform fehumah PRISCO ah havaalukurumuge hu'dha ah 2019/1025/BC03/06 Maldives Correctional Service Male' Prison Cooperative Society (PRISCO) MVR 59,500.24 edhi TES/2019/G-014 Maldives Correctional Service Supply and Delivery Of Sea Transport Vessels K. -

Coastal Adpatation Survey 2011

Survey of Climate Change Adaptation Measures in Maldives Integration of Climate Change Risks into Resilient Island Planning in the Maldives Project January 2011 Prepared by Dr. Ahmed Shaig Ministry of Housing and Environment and United Nations Development Programme Survey of Climate Change Adaptation Measures in Maldives Integration of Climate Change Risks into Resilient Island Planning in the Maldives Project Draft Final Report Prepared by Dr Ahmed Shaig Prepared for Ministry of Housing and Environment January 2011 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 COASTAL ADAPTATION CONCEPTS 2 3 METHODOLOGY 3 3.1 Assessment Framework 3 3.1.1 Identifying potential survey islands 3 3.1.2 Designing Survey Instruments 8 3.1.3 Pre-testing the survey instruments 8 3.1.4 Implementing the survey 9 3.1.5 Analyzing survey results 9 3.1.6 Preparing a draft report and compendium with illustrations of examples of ‘soft’ measures 9 4 ADAPTATION MEASURES – HARD ENGINEERING SOLUTIONS 10 4.1 Introduction 10 4.2 Historical Perspective 10 4.3 Types of Hard Engineering Adaptation Measures 11 4.3.1 Erosion Mitigation Measures 14 4.3.2 Island Access Infrastructure 35 4.3.3 Rainfall Flooding Mitigation Measures 37 4.3.4 Measures to reduce land shortage and coastal flooding 39 4.4 Perception towards hard engineering Solutions 39 4.4.1 Resort Islands 39 4.4.2 Inhabited Islands 40 5 ADAPTATION MEASURES – SOFT ENGINEERING SOLUTIONS 41 5.1 Introduction 41 5.2 Historical Perspective 41 5.3 Types of Soft Engineering Adaptation Measures 42 5.3.1 Beach Replenishment 42 5.3.2 Temporary -

List of MOE Approved Non-Profit Public Schools in the Maldives

List of MOE approved non-profit public schools in the Maldives GS no Zone Atoll Island School Official Email GS78 North HA Kelaa Madhrasathul Sheikh Ibrahim - GS78 [email protected] GS39 North HA Utheem MadhrasathulGaazee Bandaarain Shaheed School Ali - GS39 [email protected] GS87 North HA Thakandhoo Thakurufuanu School - GS87 [email protected] GS85 North HA Filladhoo Madharusathul Sabaah - GS85 [email protected] GS08 North HA Dhidhdhoo Ha. Atoll Education Centre - GS08 [email protected] GS19 North HA Hoarafushi Ha. Atoll school - GS19 [email protected] GS79 North HA Ihavandhoo Ihavandhoo School - GS79 [email protected] GS76 North HA Baarah Baarashu School - GS76 [email protected] GS82 North HA Maarandhoo Maarandhoo School - GS82 [email protected] GS81 North HA Vashafaru Vasahfaru School - GS81 [email protected] GS84 North HA Molhadhoo Molhadhoo School - GS84 [email protected] GS83 North HA Muraidhoo Muraidhoo School - GS83 [email protected] GS86 North HA Thurakunu Thuraakunu School - GS86 [email protected] GS80 North HA Uligam Uligamu School - GS80 [email protected] GS72 North HDH Kulhudhuffushi Afeefudin School - GS72 [email protected] GS53 North HDH Kulhudhuffushi Jalaaludin school - GS53 [email protected] GS02 North HDH Kulhudhuffushi Hdh.Atoll Education Centre - GS02 [email protected] GS20 North HDH Vaikaradhoo Hdh.Atoll School - GS20 [email protected] GS60 North HDH Hanimaadhoo Hanimaadhoo School - GS60 -

Maldives Four Years After the Tsunami

Maldives - 4 Years after the tsunami Progress and remaining gaps Department of National Planning Ministry of Finance and Treasury Republic of Maldives July 2009 2 Executive Summary | Ministry of Finance and Treasury - Department of National Planning Executive Summary In the four years since the tsunami, much has been accomplished to provide its survivors first with basic needs and then with the resources to restart their lives. Most of the physical infrastructure will be finished in 2009 and tsunami resources have enabled notable improvements in health and education. The challenging housing sector was brought under control and most of the remaining work will be completed in the year as well. Large-scale disruptions to livelihoods and the economy were mitigated. Lasting improvements made in disaster risk reduction policies, institutions and systems will increase resilience to future crises. Although the speed and scope of recovery in the Maldives has been impressive, a number of problems caused or worsened by the tsunami have not yet been resolved and remain priorities for government and its partners: The vital needs of water and sanitation and reconstruction of remaining infrastructure for harbours and jetties remain unfinished priorities highlighted in the analysis. Additionally, the relocation of entire island populations is clearly a complex undertaking. Completing the last of the housing and resettling remaining displaced persons (IDPs) will require attention to such details as livelihoods and social arrangements on the islands. It is inevitable that some of these processes will lag into 2010 while currently unfunded sanitation and harbour infrastructure projects will need to extend even further into the future. -

South Asia Disaster Risk Management Programme

Synthesis Report on South Asian Region Disaster Risks – Final Report South Asia Disaster Risk Management Programme: Synthesis Report on SAR Countries Disaster Risks Synthesis Report on South Asian Region Disaster Risks – Final Report Table of Content PREFACE................................................................................................................................................IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.........................................................................................................................V LIST OF FIGURES..................................................................................................................................VI ABBREVIATION USED............................................................................................................................X EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..........................................................................................................................1 1.1 BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 KEY FINDINGS ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 WAY FORWARD ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.3.1 Additional analyses .................................................................................................................................. -

A Rapid Assessment of Natural Environments in the Maldives

A rapid assessment of natural environments in the Maldives Charlie Dryden, Ahmed Basheer, Gabriel Grimsditch, Azim Mushtaq, Steven Newman, Ahmed Shan, Mariyam Shidha, Hussain Zahir A rapid assessment of natural environments in the maldives Charlie Dryden, Ahmed Basheer, Gabriel Grimsditch, Azim Mushtaq, Steven Newman, Ahmed Shan, Mariyam Shidha, Hussain Zahir The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), USAID (United States Agency for International Development), Project Regenerate or the Government of Maldives concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, USAID, Project Regenerate or the Government of Maldives. This publication has been made possible in part by funding from USAID. The facilitation required for the research has been made possible by the Ministry of Environmemt, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Marine Research Centre and the Maldives Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture. This research has been made possible with the collaboration and expertise of Banyan Tree Maldives , The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), The Marine Research Centre (MRC), M/Y Princess Rani, Scuba Centre Maldives diving fleet, Angsana Ihuru, Angsana Velavaru, Bandos Maldives, Banyan Tree Maldives, Hurawalhi Island Resort, Holiday Inn Resort Kandooma, Kuramathi Island Resort, Kuredu Island Resort and Spa, Kurumba Maldives, Shangri-La Maldives, Six Senses Laamu, Soneva Jani, Taj Exotica Resort and Spa, Maldives and Vivanta by Taj Coral Reef, Aquaventure divers Addu, Farikede Dive Centre Fuvahmulah, Blue In Dive and Watersports, Eurodivers – Kandooma, Eurodivers – Kurumba and Small Island Research Group in Fares Maathoda, Shaviyani Atoll Funadhoo council, Haa Dhaalu Atoll council and Noonu Atoll Holhudhoo council. -

Job Applicants' Exam Schedule February 2016

Human Resource Management Section Maldives Customs Service Date: 8/2/2016 Job Applicants' Exam Schedule February 2016 Exam Group 1 Exam Venue: Customs Head Office 8th Floor Date: 14 February 2016 Time: 09:00 AM # Full Name NID Permanent Address 1 Hussain Ziyad A290558 Gumreege/ Ha. Dhidhdhoo 2 Ali Akram A269279 Olhuhali / HA. Kelaa 3 Amru Mohamed Didi A275867 Narugisge / Gn.Fuvahmulah 4 Fathimath Rifua A287497 Chaman / Th.Kinbidhoo 5 Ausam Mohamed Shahid A300096 Mercy / Gdh.Gadhdhoo 6 Khadheeja Abdul Azeez A246131 Foniluboage / F.Nilandhoo 7 Hawwa Raahath A294276 Falhoamaage / S.Feydhoo 8 Mohamed Althaf Ali A278186 Hazeleen / S.Hithadhoo 9 Aishath Manaal Khalid A302221 Sereen / S.Hithadhoo 10 Azzam Ali A296340 Dhaftaru. No 6016 / Male' 11 Aishath Suha A258653 Athamaage / HA.filladhoo 12 Shamra Mahmoodf A357770 Ma.Rinso 13 Hussain Maaheen A300972 Hazaarumaage / Gdh.Faresmaathodaa 14 Reeshan Mohamed A270388 Bashimaa Villa / Sh.Maroshi 15 Meekail Ahmed Nasym A165506 H. Sword / Male' 16 Mariyam Aseela A162018 Gulraunaage / R. Alifushi 17 Mohamed Siyah A334430 G.Goidhooge / Male' 18 Maish Mohamed Maseeh A322821 Finimaage / SH.Maroshi 19 Shahim Saleem A288096 Shabnamge / K.Kaashidhoo 20 Mariyam Raya Ahmed A279017 Green villa / GN.Fuvahmulah 21 Ali Iyaz Rashid A272633 Chamak / S.Maradhoo Feydhoo 22 Adam Najeedh A381717 Samandaru / LH.Naifaru 23 Aishath Zaha Shakir A309199 Benhaage / S.Hithadhoo 24 Aishath Hunaifa A162080 Reehussobaa / R.Alifushi 25 Mubthasim Mohamed Saleem A339329 Chandhaneege / GA.Dhevvadhoo 26 Mohamed Thooloon A255587 Nooraanee Villa / R. Alifushi 27 Abdulla Mubaah A279986 Eleyniri / Gn.Fuvahmulah 28 Mariyam Hana A248547 Nookoka / R.Alifushi 29 Aishath Eemaan Ahmed A276630 Orchid Fehi / S.Hulhudhoo 30 Haroonul Rasheed A285952 Nasrussaba / Th.