Standardization of Sign Languages (SLS, Vol. 15, No. 4, Summer 2015)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies in Second Language Acquisition, Volume 22 , Issue 2, June 2000

SSLA, 22, 283±291. Printed in the United States of America. BOOK NOTICES PINKY EXTENSION AND EYE GAZE: LANGUAGE USE IN DEAF COMMUNI- TIES. Ceil Lucas (Ed.). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press, 1998. Pp. ix + 285. $55.00 cloth. This collection of ten articles constitutes the fourth volume of a series, Sociolinguistics in Deaf Communities. The book's title refers to an aspect of variation in sign languages (pinky extension) and an aspect of sign language discourse (eye gaze) and underscores the richness and uniqueness of language use in Deaf communities around the world. The ten articles are distributed among the book's six sections: variation, languages in contact, language in education, discourse analysis, second language learning, and lan- guage attitudes. Although most of the articles focus on American Sign Language (ASL), one article explores grammatical constraints on fingerspelled English verb loans in Brit- ish Sign Language, another examines the representation of character signs in Taiwan Sign Language (TSL) resulting from contact between TSL and written Chinese, and a third outlines historical, political, and educational issues affecting Irish Sign Language and the Irish Deaf community. The book's coverage of diverse sign language communi- ties is enhanced by an article exploring variation in the use of ªtactile ASLº by Deaf- Blind people, in which case a language ordinarily processed in a visual modality is com- municated through touch. The remaining articles address ASL topics such as pinky extension, conversational repairs, eye gaze and pronominal reference, and spatial mapping in ASL storytelling. An article on the relationship of educational policy to language and cognition in Deaf chil- dren provides an overview of educational policies and practices affecting Deaf children and recommends the development of a Deaf educational policy that is grounded in sci- entific sociolinguistic research and that facilitates cognitive development in Deaf chil- dren. -

Weak Hand Variation in Philadelphia ASL: a Pilot Study

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 25 Issue 2 Selected Papers from NWAV47 Article 15 1-15-2020 Weak Hand Variation in Philadelphia ASL: A Pilot Study Meredith Tamminga University of Pennsylvania Jami Fisher University of Pennsylvania Julie Hochgesang Gallaudet University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation Tamminga, Meredith; Fisher, Jami; and Hochgesang, Julie (2020) "Weak Hand Variation in Philadelphia ASL: A Pilot Study," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 25 : Iss. 2 , Article 15. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol25/iss2/15 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol25/iss2/15 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Weak Hand Variation in Philadelphia ASL: A Pilot Study Abstract In this pilot study of variation in Philadelphia ASL, we connect two forms of weak hand variability to the diachronic location asymmetries that Frishberg 1975 observed for changes between one- and two- handed sign realizations. We hypothesize that 1) variable weak hand involvement is a pathway for change from one- to two-handed and thus should be more frequent for body signs than head signs, and 2) variable weak hand lowering is a pathway for change from two- to one-handed and thus should be more frequent for head signs than body signs. Conversational data from four signers provides quantitative support for hypothesis (1) but not (2). We additionally observe differences in weak hand height based on sign location and one/two-handedness. The results motivate further work to investigate the possibility that weak hand involvement is a mechanism for diachronic change in sign languages. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO American Sign Language Poetry

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO American Sign Language Poetry: Literature in Motion A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Literatures in English by Jessica Cole Committee in charge: Professor Michael Davidson, Chair Professor Carol Padden Professor Margaret Loose 2009 Copyright Jessica Cole, 2009 All rights reserved. The Thesis of Jessica Cole is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page......................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents................................................................................................... iv List of Tables........................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgements................................................................................................. vii Abstract................................................................................................................... viii Introduction............................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One An Analysis of “Hands” by -

Sociolinguistics and Deaf Communities Edited by Adam C

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05194-2 - Sociolinguistics and Deaf Communities Edited by Adam C. Schembri and Ceil Lucas Frontmatter More information Sociolinguistics and Deaf Communities How do people use sign languages in different situations around the world? How are sign languages distributed globally? What happens when they come in contact with spoken and written languages? These and other questions are explored in this new introduction to the sociolinguistics of sign languages and Deaf communities. An international team brings insight and data from a wide range of sign languages, from the USA, Canada, England, Spain, Brazil, and Australia. Topics covered include multilingualism in the global Deaf community; sociolinguistic variation and change in sign languages; bilingualism and language contact between signed and spoken languages; attitudes toward sign languages; sign language planning and policy, and sign language discourse. Sociolinguistics and Deaf Communities will be welcomed by students of sign language and interpreting, teachers of sign language, and students and academics working in linguistics. adam c. schembri is Associate Professor on the Linguistics program and director of the Centre for Research on Language Diversity at La Trobe University. ceil lucas is Professor Emerita in the Department of Linguistics at Gallaudet University. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05194-2 - Sociolinguistics and Deaf Communities Edited by Adam C. Schembri and Ceil Lucas Frontmatter More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05194-2 - Sociolinguistics and Deaf Communities Edited by Adam C. Schembri and Ceil Lucas Frontmatter More information Sociolinguistics and Deaf Communities Edited by Adam C. -

05-06 Catalog.Indb

The University Community The University Community Patron George W. Bush President Board of Trustees Glenn B. Anderson, Chair, Arkansas Ken H. Levinson, California Cynthia W. Ashby, Georgia The Honorable John McCain, Arizona Celia May L. Baldwin, Vice Chair, California Nanette Fabray MacDougall,** California Philip W. Bravin,* South Dakota Carol A. Padden,* California Brenda Jo Brueggemann, Ohio Alexander E. Patterson,* Connecticut Susan J. Dickinson, Colorado Frank Ross, Maryland Richard A. Dysart,* California Robert G. Sanderson,* Utah Harvey Goodstein, Arizona Benjamin J. Soukup, Jr., South Dakota Mervin D. Garretson,* Delaware Christopher D. Sullivan, New Jersey Bill Graham, Secretary,Washington Charles V. Williams, Ohio Pamela Holmes, Wisconsin The Honorable Lynn Woolsey, California Tom Humphries, California Frank H. Wu, Michigan The Honorable Thomas Penfi eld Jackson,* DC John T.C. Yeh,* Maryland L. Richard Kinney, Wisconsin * Emeritus The Honorable Ray LaHood, Illinois ** Honorary 144 The University Community University Administration I. King Jordan, President; B.A., Gallaudet University; M.A., Gary B. Aller, Executive Director, Business and Support Ph.D., University of Tennessee Services; B.A., University of Washington Jane K. Fernandes, Provost; B.A., Trinity College; M.A., David F. Armstrong, Director, Budget; B.A., Ph.D., Ph.D., University of Iowa University of Pennsylvania Paul Kelly, Vice President, Administration and Finance; Deborah E. DeStefano, Executive Director, Enrollment B.S., University of Massachusetts; M.B.A., Babson College; Services; B.A., M.A., Gallaudet University J.D., George Washington University Katherine A. Jankowski, Dean, Laurent Clerc National Lindsay Dunn, Special Assistant to the President, Advocacy; Deaf Education Center; B.A., Gallaudet University; M.Ed., B.A., Gallaudet University; M.A., New York University University of Arizona; Ph.D., University of Maryland Patricia M. -

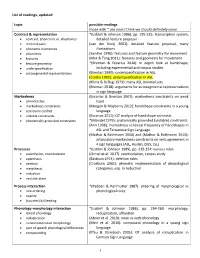

1 List of Readings, Updated Topic Possible Readings Those with * Are

List of readings, updated topic possible readings those with * are ones I think we should definitely cover Contrast & representation *(Liddell & Johnson 1986), pp. 195‐235: transcription system, contrast, phonemes vs. allophones detailed feature proposal minimal pairs (van der Kooij 2002): detailed feature proposal, many phoneme inventories illustrations phonemes (Sandler 1996): features and feature geometry for movement features (Mak & Tang 2011): features and geometry for movement feature geometry *(Brentari & Eccarius 2010): in depth look at handshape, underspecification including experimental and corpus studies autosegmental representations (Brentari 1990): underspecification in ASL (Corina 1993): underspecification in ASL (Klima & Bellugi 1979): many ASL minimal sets (Brentari 2018): arguments for autosegmental representations in sign language Markedness (Eccarius & Brentari 2007): markedness constraints on weak phonotactics hand markedness constraints (Morgan & Mayberry 2012): handshape constraints in a young constraint conflict language violable constraints (Eccarius 2011): OT analysis of handshape contrasts phonetically grounded constraints *(Mandel 1979): anatomically grounded (violable) constraints (Ann 1996): markedness vs lexical frequency of handshapes in ASL and Taiwanese Sign Language (Mathur & Rathmann 2006) and (Mathur & Rathmann 2010): articulatory markedness constraints on verb agreement in 4 sign languages (ASL, Auslan, DGS, JSL) Processes *(Liddell & Johnson 1989), pp. 235‐254: various rules assimilation, -

Language and Linguistics: Introduction | NSF - National Science Foundation

Language and Linguistics: Introduction | NSF - National Science Foundation RESEARCH AREAS FUNDING AWARDS DOCUMENT LIBRARY NEWS ABOUT NSF Language is common to all humans; we seem to be “hard-wired” for it. Many social scientists and philosophers say it’s this ability to use language symbolically that makes us “human.” Though it may be a universal human attribute, language is hardly simple. For decades, linguists’ main task was to track and record languages. But, like so many areas of science, the field of linguistics has evolved dramatically over the past 50 years or so. Languages come in many shapes and sounds. Language is simultaneously a physical process and a way of sharing meaning among people. Credit: Design by Alex Jeon, National Science Foundation Today’s science of linguistics explores: the sounds of speech and how different sounds function in a language the psychological processes involved in the use of language how children acquire language capabilities social and cultural factors in language use, variation and change the acoustics of speech and the physiological and psychological aspects involved in producing and understanding it the biological basis of language in the brain This special report touches on nearly all of these areas by answering questions such as: How does language develop and change? Can the language apparatus be "seen" in the brain? Does it matter if a language disappears? What exactly is a dialect? How can sign language help us to understand languages in general? Answers to these and other questions have implications for neuroscience, psychology, sociology, biology and more. More Special Reports Next: Speech is Physical and Mental https://www.acpt.nsf.gov/news/special_reports/linguistics1/intro.jsp[12/30/2019 3:39:39 PM] Language and Linguistics: Speech Is Physical | NSF - National Science Foundation RESEARCH AREAS FUNDING AWARDS DOCUMENT LIBRARY NEWS ABOUT NSF Humans are equipped with Click on illustrations for more detail. -

American Sign Language, Linguistics of (Valli

1-56368-097-1_cover.p70 1 9/10/03, 12:46 AM LINGUISTICS OF AMERICANSIGNLANGUAGE LINGUISTICS OF AMERICAN SIGN LANGUAGE An Introduction Third Edition CLAYTON VALLI CEIL LUCAS Clerc Books Gallaudet University Press Washington, D.C. Clerc Books An imprint of Gallaudet University Press Washington, DC 20002 © 1992 , 1995, 2000 by Gallaudet University. All rights reserved. First edition 1992 Third edition 2000 Printed in the United States of America Excerpt from Language: Its Structure and Use by Edward Finegan and Niko Bernier, copyright © 1989 by Harcourt Brace & Com- pany, reprinted by permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Valli, Clayton. Linguistics of American Sign Language : an introduction / Clayton Valli, Ceil Lucas.—3rd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-56368-097-1 1. American Sign Language—Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Lucas, Ceil. II. Title. HV2474 .V35 2001 419—dc21 00-064369 oThe paper used in this publication meets the minimum re- quirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. For William C. Stokoe and for our students “In 1960, when Sign Language Structure and The Calculus of Structure were published . they argued that paying attention to sign language could only interfere with the students’ proper education.” William C. Stokoe May 1988 “The language [ASL] I finally discovered when I was 14 years old made me understand what’s happening around me. For the first time, I understood what was happening and finally started to learn. Now my education brain is blossoming.” Gallaudet undergraduate November 1990 Contents Preface to the Third Edition xi Acknowledgments xiii Introduction xv PART ONE BASIC CONCEPTS Basic Concepts 1 PART TWO PHONOLOGY Unit 1 Signs Have Parts 19 Unit 2 The Stokoe System 25 Unit 3 The Concept of Sequentiality in the Description of Signs 30 Unit 4 The Movement–Hold Model 37 Unit 5 Phonological Processes 42 Unit 6 Summary 47 PART THREE MORPHOLOGY Unit 1 Phonology vs. -

Carla D. Morris Linkedin.Com/In/Carla-D-Morris Carladmorris.Wordpress.Com

1 Carla D. Morris linkedin.com/in/carla-d-morris carladmorris.wordpress.com Academic Background PhD Linguistics Gallaudet University, Washington, DC May 2016 MA Linguistics Gallaudet University, Washington, DC May 2011 AA American Sign Language Berkeley City College, Berkeley, CA May 2008 BA Linguistics University of California, Berkeley, CA Dec. 2004 AA Liberal Arts Santa Rosa Junior College, Santa Rosa, CA May 2002 Professional Background Technical language support specialist July 2016–Present Language Research Center, JTG, Inc., Hyattsville, MD Supervised by Dr. Alina Newland Editorial staff May 2011–July 2016 Gallaudet University Press, Washington, DC Supervised by Ivey Wallace Department representative, Linguistics Jan. 2014–Aug. 2015 Graduate Student Association, Gallaudet University, Washington, DC Research assistant Sept. 2013–Sept. 2014 Department of Linguistics, Gallaudet University, Washington, DC Supervised by Dr. Kristin Mulrooney Adjunct professor, LIN510: Language Acquisition Aug. 2012–Dec. 2012 Department of Linguistics, Gallaudet University, Washington, DC Supervised by Dr. Deborah Chen Pichler Teaching assistant, LIN510: Language Acquisition Aug. 2011–Dec. 2011 Department of Linguistics, Gallaudet University, Washington, DC Supervised by Dr. Deborah Chen Pichler Research assistant Aug. 2010–Sept. 2011 Department of Linguistics, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT Supervised by Dr. Diane Lillo-Martin Digital archivist (internship) June 2010–Aug. 2010 The Rosetta Project, The Long Now Foundation, San Francisco, CA Supervised by Dr. Laura Welcher Department assistant Jan. 2010–June 2010 Department of Linguistics, Gallaudet University, Washington, DC Teambuilding and leadership facilitator Feb. 2008–Aug. 2009 Four Winds Ropes Course, Santa Rosa, CA Residential counselor Feb. 2009–July 2009 Deaf & HoH program, Willow Creek Treatment Center, Santa Rosa, CA Classroom aide & tutor (internship) June 2008–Aug. -

The Importance of the Sociohistorical Context in Sociolinguistics: the Case of Black ASL

JOSEPH C. HILL The Importance of the Sociohistorical Context in Sociolinguistics: The Case of Black ASL Abstract The article discusses the importance of sociohistorical context which is the foundation of variation studies in sociolinguistics.The studies on variation in spoken and signed languages are reviewed with the discussion of geographical and social aspects which are treated as external factors in the formation and maintenance of dialects and those factors often have historical roots. The Black ASL project is reviewed as a case with racial segregation and educational policies as part of the sociohistorical factors in the emergence of Black ASL. The foundation of variationist sociolinguistics is the socio- historical context in which people use language.1 Linguistic factors can contribute to variation in language, but geographical boundaries and social factors also play a role (Wolfam and Schilling-Estes 2006). External factors (e.g., age, location, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, identity) have been examined since the seminal variation stud- ies done by trailblazing fgures such as William Labov, Roger Shuy, and Walt Wolfram. However, the term sociolinguistics was not originally accepted as descriptive of the discipline:“I have resisted the term socio- linguistics for many years, since it implies that there can be a successful linguistic theory or practice which is not social” (Labov 1972, xii). In Joseph C. Hill is assistant professor in the Department of ASL and Interpreting Education at the National Technical Institute for the Deaf. 41 Sign Language Studies Vol. 18 No. 1 Fall 2017 42 | Sign Language Studies other words, social and geographical factors do not invalidate a lin- guistic theory as a scientifc explanation of language variation. -

1 Introduction

Cambridge University Press 0521791375 - The Sociolinguistics of Sing Languages Edited by Ceil Lucas Excerpt More information 1 Introduction Ceil Lucas Recent history has included some major events in both the American Deaf community∗ and around the world, and many of the events have been funda- mentally sociolinguistic in nature. For example, 13 years ago, in March 1988, the campus of Gallaudet University erupted into a week of protests stemming from the selection of Elizabeth Zinser as the seventh president of the 124-year- old institution. The outcomes of the Deaf President Now (DPN) movement are history: the resignation of the newly appointed president and of the chairman of the Board of Trustees, the reconstitution of the board to contain a majority of deaf people, the selection of a deaf president and the promise of no reprisals against the protesters. In The Sociolinguistics of Society, Ralph Fasold (1984) observes that the essence of sociolinguistics depends on two facts about language: first, that lan- guage varies, which is to say that “speakers have more than one way to say more or less the same thing” (p. ix); and, second, that language serves a broadly encompassing purpose just as critical as the obvious one of transmitting infor- mation and thoughts from one person to another. Namely, language users use language to make statements about who they are, what their group loyalties are, how they perceive their relationship to interlocutors and what kind of speech event they consider themselves to be involved in. Critical to an understand- ing of the events at Gallaudet University is the critical purpose that language serves in defining one’s identity, group loyalty, relationship to interlocutors and understanding of the speech event. -

The Hidden Treasure of Black ASL: Its History and Structure

The Hidden Treasure of Black ASL: Its History and Structure Book & DVD by Carolyn McCaskill, Ceil Lucas, Robert Bayley & Joseph Hill Gallaudet University Press 2011 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction Chapter 2: The Socio-historical Foundation Chapter 3: How We Did the Study Chapter 4: Perceptions Chapter 5: Phonological Variation Chapter 6: Variation in Syntax and Discourse Chapter 7: The Effects of Language Contact Chapter 8: Lexical Variation Chapter 9: Conclusions The Basic Question for Our Project: What are the features of the variety of American Sign Language (ASL) that people call “Black ASL”? •There are many anecdotal reports about its existence: “Yeah, I see something different…” •We have considerable evidence of differences in individual signs (lexical variation). Project Questions and Goals 2 Hairston & Smith (1983): there is a “Black way of signing used by Black deaf people in their own cultural milieu – among families and friends, in social gatherings, and in deaf clubs” (55). There also exists a 50-year tradition of research on African American Vernacular English (AAVE) showing that AAVE is a distinct variety of English (see Mufwene et al. 1998 and Green 2004 for reviews). ◦ Unique features have been identified at all levels of the language: phonology morphology syntax lexicon Project Questions and Goals 3 Can the same kind of unique features that have been identified for AAVE be identified for Black ASL, to show that it is a distinct variety of ASL? That is the focus of our project. BUT, there is a question that