Psychosocial and Symbolic Dimensions of the Breast Explored Through a Visual Matrix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Brassiere in the 20Th Century

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 12-10-2012 The Evolution of Brassiere in the 20th Century Jolene Khor Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Khor, Jolene, "The Evolution of Brassiere in the 20th Century" (2012). Honors Theses. 2342. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2342 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: The Evolution of Brassiere in the 20th Century 1 The Evolution of Brassiere in the 20th Century Jolene Khor Western Michigan University The Evolution of Brassiere in the 20th Century 2 Abstract It is common knowledge that a brassiere, more widely known as a bra, is an important if not a vital part of a modern woman’s wardrobe today. In the 21st century, a brassiere is no more worn for function as it is for fashion. In order to understand the evolution of function to fashion of a brassiere, it is necessary to account for its historical journey from the beginning to where it is today. This thesis paper, titled The Evolution of Brassiere in the 20th Century will explore the history of brassiere in the last 100 years. While the paper will briefly discuss the pre-birth of the brassiere during Minoan times, French Revolution and early feminist movements, it will largely focus on historical accounts after the 1900s. -

Depictions of Empowerment? How Indian Women Are Represented in Vogue India and India Today Woman a PROJECT SUBMITTED to the FACU

Depictions of Empowerment? How Indian Women Are Represented in Vogue India and India Today Woman A PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Monica Singh IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LIBERAL STUDIES August 2016 © Monica Singh, 2016 Contents ILLUSTRATIONS........................................................................................................................ ii INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1 .................................................................................................................................. 5 CHAPTER 2 ................................................................................................................................ 19 CHAPTER 3 ................................................................................................................................ 28 CHAPTER 4 ................................................................................................................................ 36 CHAPTER 5 ................................................................................................................................ 53 CHAPTER 6 ................................................................................................................................ 60 REFLECTION FOR ACTION................................................................................................. -

Victoria's Secret As a Do-It-Yourself Guide Lexie Kite University of Utah

Running Head: VS as a Do‐It‐Yourself Guide 1 From Objectification to Self-Subjectification: Victoria’s Secret as a Do-It-Yourself Guide Lexie Kite University of Utah Third-Year Doctoral Student Department of Communication 1 Running Head: VS as a Do‐It‐Yourself Guide 2 In the U.S. and now across the world, a multi-billion-dollar corporation has been fighting a tough battle for female empowerment since 1963, and according to their unmatched commercial success, women appear to be quite literally buying what this ubiquitous franchise is selling. Holding tight to a mission statement that stands first and foremost to “empower women,” and a slogan stating the brand is one to “Inspire, Empower and Indulge,” the franchise “helps customers to feel sexy, bold and powerful” (limitedbrands.com, 2010). This is being accomplished through the distribution of 400 million catalogs to homes each year, a constant array of television commercials all hours of the day, a CBS primetime show viewed by 100 million, and 1,500 mall storefront displays in the U.S. alone (VS Annual Report, 2009). And to the tune of 5 billion dollars every year, women are buying into the envelope-pushing “empowerment” sold by Victoria’s Secret, the nation’s premiere lingerie retailer. Due to Victoria’s Secret’s ubiquitous media presence and radical transformation from a modest, Victorian-era boutique to a sexed-up pop-culture phenomenon in the last decade, a critical reading of VS’s media texts is highly warranted. Having been almost completely ignored in academia, particularly in the last 15 years as the company has morphed from a place for men to shop for women to a women-only club (Juffer, 1996, p. -

It's All in the Details: Making an Early 19Th Century Ball Gown by Hope Greenberg

It's All in the Details: Making an early 19th Century Ball Gown By Hope Greenberg In 1775, the year of Jane Austen’s birth, women wore gowns with a fitted bodice, the waist at or below the natural waistline, and full skirts over a visible, often ornate, petticoat. They were made in a variety of heavy silks, cotton or wool. By the time she had reached her late teens the ornate gowns were being replaced by simple, lightweight, often sheer cotton or silk gowns that reflected the ideals of classicism. This guide provides images and details to consider when creating an early 19th century ballgown. The examples provide a general guide, not an exact historic timeline. Fashion is flexible: styles evolve and are adopted at a different pace depending on the wearer's age, location, and economic or social status. These examples focus on evening or ball gowns. Day dresses, walking dresses, and carriage dresses, while following the same basic silhouettes, have their own particular design details. Even evening gowns or opera gowns can usually be distinguished from ball gowns which, after all, must be designed for dancing! By focusing on the details we can see both the evolution of fashion for this period and how best to re-create it. What is the cut of the bodice, the sleeve length, or the height of the bustline? How full is the skirt, and where is that fullness? What colors are used? What type of fabric? Is there trim? If so, how much, what kind, and where is it placed? Based on the shape of the gown, what can we tell about the foundation garments? Paying attention to all these details will help you create a gown that is historically informed as well as beautiful. -

Patriarchy and Prejudice: Indian Women and Their Cinematic Representation

International Journal of Languages, Literature and Linguistics, Vol. 3, No. 3, September 2017 Patriarchy and Prejudice: Indian Women and Their Cinematic Representation Abina Habib social and cultural roles, which carry into the mainstream Abstract—Nurtured by Indian culture and history women’s film industry and they end up being cast in similar roles. role in commercial Indian films is that of a stereotypical woman, Inspired by ‘Manusmriti’- an age old Dharmashastra written from the passive wife of Dadasaheb Phalke’s Raja by Manu for followers of Hindu faith – a female actor is Harishchandra’ (1913) to the long-suffering but heroic mother-figure of Mother India (1957) to the liberated Kangana never allowed to transgresses the scriptural paradigm that Ranaut of Queen (2014), it has been a rather long and mediates women's role as always in obedience and servitude challenging journey for women in Hindi cinema. Although this to man, like Sita – the scriptural paradigm of femininity. The role has been largely redefined by the Indian woman and beginning of the woman's acting career seems to be governed reclaimed from the willfully suffering, angelic albeit voiceless by social norms and they mostly ended up playing the roles of female actor, the evolution is still incomplete. Culture and tradition mean different things for different women, but there is a daughter, taking care of her siblings, helping the mother in always the historical context of what it entails in the form of the kitchen, and marrying the man of her father's choice, ownership. What this paper seeks to unravel is what being a another typical role assigned to women is that of a great woman means in Indian cinema. -

Getting a Grip on the Corset: Gender, Sexuality and Patent Law

2011.4.20 A SWANSON.DOCM (DO NOT DELETE) 4/20/11 7:33 PM Getting a Grip on the Corset: Gender, Sexuality and Patent Law Kara W. Swanson* PART I. TOWARD A FEMINIST APPROACH TO PATENT LAW ........................... 105 A. Identifying the Tools.................................................................... 105 B. Starting with the Corset................................................................ 108 C. An Archaeology of a Case ........................................................... 110 PART II. THE CORSET AS TECHNOLOGY ......................................................... 116 A. Corset Patents and Patentees........................................................ 119 B. Corset Patent Litigation in the New York Metropolitan Area ..... 123 C. Construing a Corset Patent........................................................... 127 1. Cohn v. United States Corset Company................................. 128 2. “Grace” and “Elegance” as Terms of Art .............................. 130 PART III. THE CORSET IN PUBLIC AND PRIVATE ............................................ 132 A. The Dual Nature of Corsets.......................................................... 133 B. The Corset as Witness.................................................................. 137 PART IV. FRANCES EGBERT AND THE BARNES PATENT.................................. 139 A. Reissues and Early Litigation....................................................... 139 B. Egbert v. Lippmann, Twice.......................................................... 142 1. The -

The Silky Strategy of Victoria's Secret

The Silky Strategy of Victoria’s Secret Chelsea Chi Chang Alice Lin Charlene Mak BEM 106: Strategy Professor McAfee 28 May 2004 1 Victoria's Secret is a retail brand of lingerie and beauty products, owned and run by the Limited Brands company. Victoria’s Secret generates more than $4 billion in sales a year. It is the fastest growing subsidiary of Limited Brands and contributes 42% of corporate profits. More than 1000 Victoria's Secret retail stores are open in the United States. Products are also available through the catalogue and online business, Victoria's Secret Direct, with sales of approximately $870 million. Victoria’s Secret was established by Roy Raymond in the San Francisco area during the 1970s. Raymond saw an opportunity in taking “underwear” of the time and turning it into fashion. Products stood apart from the traditional white cotton pieces, which department stores offered, with colors, patterns and style that gave them more allure and sexiness. They combined European elegance and luxury. Even the name Victoria’s Secret was meant to conjure up images of 19th-century England. The store went so far as to list a fake London address for the company headquarters. Like Starbucks, Victoria’s Secret markets self-indulgence at an affordable price. By 1982, Raymond had opened six stores and launched a modest catalog operation. He then sold Victoria’s Secret to Limited Brands, which took Victoria’s and sprinted away. Today, Victoria’s Secret enjoys nearly a monopoly position on the retail of intimate apparel in the US. The typical bra that once sold for $15 at Victoria’s Secret, when the company first opened and was worried about competition, now sells for just under $30. -

In Pursuit of the Fashion Silhouette

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Fillmer, Carel (2010) The shaping of women's bodies: in pursuit of the fashion silhouette. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/29138/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/29138/ THE SHAPING OF WOMEN’S BODIES: IN PURSUIT OF THE FASHION SILHOUETTE Thesis submitted by CAREL FILLMER B.A. (ArtDes) Wimbledon College of Art, London GradDip (VisArt) COFA UNSW for the degree of Master of Arts in the School of Arts and Social Sciences James Cook University November 2010 Dedicated to my family Betty, David, Katheryn and Galen ii STATEMENT OF ACCESS I, the undersigned, author of this work, understand that James Cook University will make this thesis available for use within the University Library and, via the Australian Digital Theses network, for use elsewhere. I understand that, as an unpublished work, a thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act and; I do not wish to place any further restriction on access to this work. Signature Date iii ELECTRONIC COPY I, the undersigned, the author of this work, declare that the electronic copy of this thesis provided to the James Cook University Library is an accurate copy of the print thesis submitted, within the limits of the technology available. -

Getting a Grip on the Corset: Gender, Sexuality, and Patent Law

Getting a Grip on the Corset: Gender, Sexuality, and Patent Law Kara W. Swanson* ABSTRACT: Over twenty years ago, Susan Brownmiller stressed the need to "get[] a grip on the corset" when considering femininity. In patent law, the "corset case," Egbert v. Lippmann (1881), is a canonical case explicating the public use doctrine. Using a historical exploration of Egbert, this paper seeks to "get[] a grip" on the corset as part of the burgeoning project to consider the intersections of gender and intellectual property from a feminist perspective. The corset achieved the pinnacle of its use by American women during the decades between the Civil War and the turn of the twentieth century. It was both the near-constant companion of the vast majority of women in the United States and a technological wonder. Like the more celebrated technologies of the era, such as the telephone, the telegraph, and the light bulb, the corset was the product of many inventors, who made and patented improvements and fought about their rights in court. As American women donned their corsets, they had a daily intimate relationship with a heavily patent-protected technology. The corset was deeply embedded both within the social construction of gender and sexuality as a marker of femininity and respectability, and within the United States patent system, as a commercial good in which many claimed intellectual property rights. Getting a grip on the corset, then, offers a way to simultaneously consider gender, sexuality, and patent law. After a consideration of what it means to make a feminist analysis of patent law in Part I, in Part II, I detail the history of the corset as an invention, using patent records, published opinions, and archival court records. -

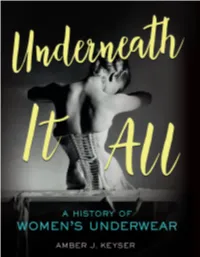

Amber J. Keyser

Did you know that the world’s first bra dates to the fifteenth century? Or that wearing a nineteenth-century cage crinoline was like having a giant birdcage strapped around your waist? Did you know that women during WWI donated the steel stays from their corsets to build battleships? For most of human history, the garments women wore under their clothes were hidden. The earliest underwear provided warmth and protection. But eventually, women’s undergarments became complex structures designed to shape their bodies to fit the fashion ideals of the time. When wide hips were in style, they wore wicker panniers under their skirts. When narrow waists were popular, women laced into corsets that cinched their ribs and took their breath away. In the modern era, undergarments are out in the open. From the designer corsets Madonna wore on stage to Beyoncé’s pregnancy announcement on Instagram, lingerie is part of everyday wear, high fashion, fine art, and innovative technological advances. This feminist exploration of women’s underwear— with a nod to codpieces, tighty- whities, and boxer shorts along the way—reveals the intimate role lingerie plays in defining women’s bodies, sexuality, gender identity, and body image. It is a story of control and restraint but also female empowerment and self- expression. You will never look at underwear the same way again. REINFORCED BINDING AMBER J. KEYSER TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY BOOKS / MINNEAPOLIS For Lacy, who puts the voom in va-va-voom Cover photograph: Photographer Horst P. Horst took this image of a Mainbocher corset in 1939. It is one of the most iconic photos of fashion photography. -

The Skewed Subject a Topological Study Of

THE SKEWED SUBJECT A TOPOLOGICAL STUDY OF SUBJECTIVITY IN BOLLYWOOD FILMS By SOUMITRA GHOSH Bachelor of Arts in English University of Calcutta Kolkata, India 2001 Master of Arts in English University of Calcutta Kolkata, India 2003 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY July, 2012 THE SKEWED SUBJECT A TOPOLOGICAL STUDY OF SUBJECTIVITY IN BOLLYWOOD FILMS Dissertation Approved: Dr. Martin Wallen Dissertation Adviser Dr. Brian Price Dr. Brian Jacobson Dr. Jennifer Borland Outside Committee Member Dr. Sheryl A. Tucker Dean of the Graduate College . ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page INTRODUCTION: LACANIAN FILM THEORY AND POST-THEORY ................ 1 Section I: The Excision ........................................................................................... 1 Section II: Many Lacans: A Review of Psychoanalytic Film Theory .................. 10 Section III: Argument and Chapter Overview ...................................................... 31 Section IV: Chapter Overview .............................................................................. 34 I. THE SUBJECT’S TEMPORALITY: RETROACTION AND ANTICIPATION IN THE DESIRE FOR HISTORY ............................................................................. 36 Section I: Three Temporal Lines .......................................................................... 48 Section II: The Error that Binds ........................................................................... -

Elizabethan Underpinnings for Women

1 2 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................. 5 16th Century Costume Timeline ................................................. 6 Overview of an Elizabethan Outfit ............................................. 7 History of the Elizabethan Corset ............................................. 12 Corset Materials ......................................................................... 19 Making a Corset Pattern............................................................ 27 Corset Measurement Form ........................................................ 29 Making an Elizabethan Corset .................................................. 30 Wearing & Caring for your Corset ........................................... 39 History of the Spanish Farthingale ........................................... 41 Farthingale Materials ................................................................. 44 Making a Spanish Farthingale .................................................. 45 Bumrolls & French Farthingales .............................................. 49 Making a Roll .............................................................................. 51 Elizabethan Stockings: History & Construction ..................... 53 Elizabethan Smocks.................................................................... 59 Making a Smock ......................................................................... 62 Appendix A: Books on Elizabethan Costume .......................... 66 Appendix