5. the Preacher and God's Word

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prepare for Lift Off! Pastor of Tenth Church and Boice’S Pulpit Hero

My final meeting with James Boice took place about ten years later, just a few The final payment of $150 for the Sr. High beach days before he died. A group of us from the church had gone to his home to see Upcoming Events him for a last time and to sing some of the hymns he had written and which were trip is due to Gabe by Sunday, June 27. set to music by Paul Jones. The last of these hymns we sang was in my view June 18 Senior High Dinner Boice’s best: Come to the Waters, a hymn gathering together all the “water of life” June 19 VBS Workday The final payment of $200 for Jr. High camp themes in the Bible as they flow from the gospel. (If you want to feel the very June 20 The Lord’s Supper at the Evening Worship Service is due to Seth by Sunday, June 27. heart-beat of James Boice’s ministry, just sing this hymn!) Sitting on the couch June 21 No Young At Heart with Jim afterwards, he grabbed my arm and in his cancer-weakened voice he June 21-25 Vacation Bible School Music Notes said to me, “Rick, do you see what I am saying in that hymn? It all flows to Jesus June 23 CE Committee Meeting and out from him. Don’t ever forget that!” By God’s grace, I don’t believe I ever June 27 St. Andrews Youth Choir-Evening Worship Service This Sunday morning, June 20, (Father’s Day), the Wee Worship Choir will will forget it, and I will certainly never forget the inspirational, Christ-centered June 27 Evangelism/Church Growth Committee Meeting sing the introit for the 11:00 am worship service. -

BOICE, Apocalypse.Indd 1 1/27/20 3:28 PM BOICE, Apocalypse.Indd 2 1/27/20 3:28 PM Seven Churches Four Horsemen One Lord Lessons from the Apocalypse

Seven Churches Four Horsemen One Lord BOICE, Apocalypse.indd 1 1/27/20 3:28 PM BOICE, Apocalypse.indd 2 1/27/20 3:28 PM Seven Churches Four Horsemen One Lord Lessons from the ApocalypsE James Montgomery Boice EDITED BY PHILIP GRAHAM RYKEN R BOICE, Apocalypse.indd 3 2/4/20 12:55 PM If you find this book helpful, please consider writing a review online. Or write to P&R at [email protected] with your comments. We’d love to hear from you. © 2020 by Linda M. Boice All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, pho- tocopy, recording, or otherwise—except for brief quotations for the purpose of review or comment, without the prior permission of the publisher, P&R Publishing Company, P.O. Box 817, Phillipsburg, New Jersey 08865-0817. Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from the ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked (NIV) are from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®. NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. All rights reserved. Italics within Scripture quotations indicate emphasis added. Excerpt from Genesis Vol. 1 by James Montgomery Boice, copyright © 1982, 1998. Used and adapted for this work by permission of Baker Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group. Excerpts from More Than Conquerors by William Hendriksen, copyright © 1940, 1967. -

The Foundation of Biblical Authority

FRANCIS A. SCHAEFFER JOHN H. GERSTNER R.C. SPROUL JAMES I. PACKER JAMES MONTGOMERY BOICE GLEASON L. ARCHER KENNETH S. KANTZER Edited by James Montgomery Boice Pickering & Inglis llLONDON · GLASGOW Copyright© 1978 by The Zondervan Corporation Grand Rapids, Michigan Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: The Foundation of Biblical authority. I. Bible-Evidences, authority, etc. I. Schadler, Francis August. II. Boice,James Montgomery, 1938- BS480.F68 220.1'3 78-12801 Pickering & Inglis edition first published 1979 ISBN O 7208 0437 X Cat. No. 01/0620 This edition is issued by special arrangement with Zondervan Publishing House the American publishers. The chapter by Kenneth S. Kantzer, "Evangelicals and the Doctrine of Inerrancy," is adapted from Evangelical Roots, edited by Kenneth S. Kantzer (Nashville: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1978) and is used by permission. It has also appeared in an adapted form in Christianif, Today (April 21, 1978). All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means-electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other-except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Printed in Great Britain by Lowe & Brydone Printers Limited, Thetford, Norfolk, for PICKERING & INGLIS LTD., 26 Bothwell Street, Glasgow G2 6PA. To Him whose Word will never pass away CONTENTS PREFACE: THE INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL ON BIBLICAL INERRANCY 9 FOREWORD: GOD GIVES HIS PEOPLE A SECOND OPPORTUNITY Francis A. Schaeffer 15 l. THE CHURCH'S DOCTRINE OF BIBLICAL INSPIRATION John H. Gerstner 23 2. -

Copyright © 2018 Evan Todd Fisher All Rights Reserved. the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary Has Permission to Reproduce A

Copyright © 2018 Evan Todd Fisher All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. STRENGTHEN WHAT REMAINS: THE RHETORICAL SITUATION OF JAMES MONTGOMERY BOICE __________________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________ by Evan Todd Fisher December 2018 APPROVAL SHEET STRENGTHEN WHAT REMAINS: THE RHETORICAL SITUATION OF JAMES MONTGOMERY BOICE Evan Todd Fisher Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Hershael W. York (Chair) __________________________________________ Robert A. Vogel __________________________________________ Michael A. G. Haykin Date ______________________________ To the memory of James Montgomery Boice A tireless champion for the Word of God TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES . vii PREFACE . viii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION . 1 Thesis . 6 Background . 18 Methodology . 22 2. THE RISE OF LIBERALISM IN NORTHERN MAINLINE PRESBYTERIANISM . 26 Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy . 27 Conclusion . 51 3. STRENGTHENING WHAT REMAINS: BOICE’S STRUGGLE WITH THE UPCUSA . 53 The Rise of Neo-Orthodoxy in Mainline Presbyterianism . 53 Ecumenism and the Confession of 1967 . 55 Boice Begins at Tenth and Disagrees with UPCUSA . 61 Working for Change from Within . 76 4. MENTORS THAT SHAPED THE LIFE AND MINISTRY OF JAMES BOICE . 93 Donald Grey Barnhouse . 94 Harold John Ockenga . 99 Robert J. Lamont . 105 iv Chapter Page John Gerstner . 109 Conclusion . 114 5. PROCLAMATION FOR REFORMATION: SERMONS AND WRITINGS OF JAMES BOICE . 116 Strategic Sermons . 116 Genesis . 119 The Gospel of John . -

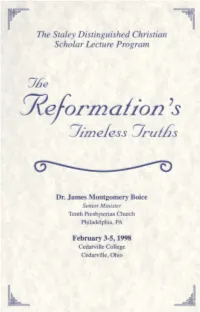

1998 Program Overview

The Staley Distinguished Christian Scholar Lecture Program Jhe Y?ejormai10n 's J;mefess 7ru!.hs G Dr. James Montgomery Boice Senior Minister Tenth Presbyterian Church Philadelphia, PA February 3-5, 1998 Cedarville College Cedarville, Ohio 7£e Y?ejormalion 's 7tmefess 7rul.hs Thesday, February 3 10 a.m. Chapel* "Scripture Alone" Wednesday, February 4 lOa.m. Chapel* "Christ Alone, Grace Alone, Faith Alone" Thursday, February 5 10 a.m. Chapel* "Glory to God Alone" *Audio cassettes are available from CDR Radio, 937-766-7815. This lectureship program has been graciously funded by the Thomas F. Staley Foundation of Larchmont, New York. This private, non-profit organization seeks to support men and women who truly believe, cordially love, and actively propagate the Gospel of Jesus Christ in its historical and scriptural fullness. It desires to enrich the quality of Christian service and sharpen the effectiveness of Christian witness, especially at the college level. Cedarville College publicly thanks the Thomas F. Staley Foundation for making this annual lectureship program possible. Beclurer Dr. James M. Boice is senior minister of Philadelphia's Tenth Presbyterian Church, one of America's most vital inner-city churches. He is also known nationwide for his incisive Bible teaching on the Bible Study Hour radio broadcast, and he serves on the Board of Directors for Bible Study Fellowship. Dr Boice received degrees from Harvard, Princeton Theological Seminary and the University of Basel, Switzerland. He is the author of nearly 50 books, including Foundations ofthe Christian Faith, Mind Renewal in a Mindless Age, and his newest book, Two Cities, Two Loves, Christian Responsibility in a Crumbling Culture. -

The Doctrines of Grace: Rediscovering the Evangelical Gospel Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE DOCTRINES OF GRACE: REDISCOVERING THE EVANGELICAL GOSPEL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Montgomery Boice,Philip Graham Ryken,R. C. Sproul | 240 pages | 30 Apr 2009 | CROSSWAY BOOKS | 9781433511288 | English | Wheaton, IL, United States The Doctrines of Grace: Rediscovering the Evangelical Gospel PDF Book You save. It was lost in the Christian bookstore, somewhere between the self-help section and the aisle full of Jesus merchandise. It was lost in the church study, when the minister decided to give his people what they wanted rather than what they needed. It is a great reminder of what God has done for us, and how much of modern Evangelicalism is Arminianism, and even leans towards Pelagianism. The truth is exactly the opposite, namely, that the doctrines of grace establish the most solid foundation and provide the most enduring motivation for the most effective proclamation of the gospel. The title might suggest that this book is about grace or the evangelical teaching of the gospel. Quick view. In the chapter on Perseverance of the Saints, the authors give their understandings of passages such as Heb p. I would only recommend to those firmly rooted in their own beliefs about salvation and God's sovereignty. Reading this book feels like a nice morsel of the 'solid food' mentioned in Hebrews. Home 1 Books 2. Search by title, catalog stock , author, isbn, etc. Most pastors and church leaders today would heartily agree with the diagnosis, but maybe not with the prescription. Boice started writing the book but was not able to finish it due to sickness, and later, his death. -

Xu2020 Redacted.Pdf (2.146Mb)

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Theology as the Wetenschap of God: Herman Bavinck’s Scientific Theology for the Modern World Ximian Xu (徐西面 ) Word Count: 100,000 Submitted for the Degree of the Doctorate in Systematic Theology The University of Edinburgh 2020 1 Declaration This thesis is entirely original research (1) that has been composed entirely by myself; and (2) that has been solely the result of my own work; and (3) that has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Unless otherwise indicated, all translations of the original texts are mine. When published English translations are available, notes have been made if the translations are cited yet revised. Ximian Xu 2 For Lajie Wang (王拉洁) -

The Doctrines of Grace: Rediscovering the Evangelical

DoctrinesOfGrace.11288.int.qxd 2/23/09 2:19 PM Page 3 CROSSWAY BOOKS WHEATON, ILLINOIS DoctrinesOfGrace.11288.int.qxd 2/23/09 2:19 PM Page 4 The Doctrines of Grace Original edition copyright © 2002 by Linda McNamara Boice and Philip Graham Ryken Published by Crossway Books a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers 1300 Crescent Street Wheaton, Illinois 60187 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided by USA copyright law. Cover design: Chris Tobias First printing, trade paper, 2009 Printed in the United States of America Unless otherwise noted, Scripture is from The Holy Bible: New International Version.® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. All rights reserved. The “NIV” and “New International Version” trademarks are registered in the United States Patent and Trademark Office by International Bible Society. Use of either trademark requires the permission of International Bible Society. Scripture references marked RSV are from the Revised Standard Version. Copyright © 1946, 1952, 1971, 1973 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. Scripture references marked KJV are from the King James Version of the Bible. ISBN: 978-1-4335-1128-8 PDF ISBN: 978-1-4335-0946-9 Mobipocket ISBN: 978-1-4335-0947-6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Boice, James Montgomery, 1938–2000 The doctrines of grace : rediscovering the evangelical gospel / James Montgomery Boice, Philip Graham Ryken. -

A Complete Introduction to the Tenets of Christianity in One Systematic Volume, James Montgomery Boice Provides a Readable Overview of Christian Theology

THEOLOGY AND HISTORY A Complete Introduction to the Tenets of Christianity In one systematic volume, James Montgomery Boice provides a readable overview of Christian theology. Both students and pastors will benefit from this rich source that covers all the major doctrines of Christianity. With scholarly rigor and a pastor’s heart, Boice carefully opens the topics of the nature of God, the character of his natural and special revelation, the fall, and the person and work of Christ. He then goes on to consider the work of the Holy Spirit in justification and sancti- fication. The book closes with careful discussion of ecclesiology and eschatology. This updated edition includes a foreword by Philip Ryken and a section-by-section study guide. Both those long familiar with Boice and those newly introduced to him will benefit from his remarkable practicality and thoroughness, which will continue to make this a standard reference for years to come. “This classic overview of Christian faith is a masterful balance of often opposing qualities. It is simultaneously comprehensive yet readable. It is accessible for serious believers, seeking college students, and newcomers to the faith. It is warmly pastoral yet theologically rich. This monumental harvest of Dr. Boice’s ministry belongs in every serious Christian’s study.” —PETER A. LILLBACK Westminster Theological Seminary INTRODUCTORY JANUARY 2019 “Over the course of the forty years or so since it was first published, 790 pages, hardcover, 978-0-8308-5214-7, $50.00, W this book by James Montgomery -

Foundations of the Christian Faith, Revised in One Volume: a Comprehensive Readable Theology Online

Tt95M [Online library] Foundations of the Christian Faith, Revised in One Volume: A Comprehensive Readable Theology Online [Tt95M.ebook] Foundations of the Christian Faith, Revised in One Volume: A Comprehensive Readable Theology Pdf Free James Montgomery Boice ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #6897722 in Books 2017-01-31Formats: Audiobook, CDOriginal language:EnglishPDF # 26 7.00 x 7.00 x 2.00l, Running time: 115140 secondsBinding: Audio CD1 pages | File size: 34.Mb James Montgomery Boice : Foundations of the Christian Faith, Revised in One Volume: A Comprehensive Readable Theology before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Foundations of the Christian Faith, Revised in One Volume: A Comprehensive Readable Theology: 2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. A Substantive Yet Easy Read!By sbdI am a James Montgomery Boice fan! I have always appreciated his scholarship and Christian integrity. I also appreciate the fact that his writing - and his preaching - is never an opportunity to showcase three+ syllable words. Mr. Boice's language makes any of his sermons and any of his books available to anyone who hungers to grow in Christian truth!1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Review of Foundations of the Christian FaithBy James R. Carmichael, Jr.I ordered this work for our students in Haiti because it is so accessible and readable, which these students desperately need. Dr. Boice did us all a favor when he left us this work. For the beginner to Reformed Theology, this is a must.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful.