From Racist to Anti-Apartheid Activist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re-Creating Home British Colonialism, Culture And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) RE-CREATING HOME BRITISH COLONIALISM, CULTURE AND THE ZUURVELD ENVIRONMENT IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY Jill Payne Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Paul Maylam Rhodes University Grahamstown May 1998 ############################################## CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ..................................... p. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................... p.iii PREFACE ................................................... p.iv ABSTRACT .................................................. p.v I: INTRODUCTION ........................................ p.1 II: ROMANCE, REALITY AND THE COLONIAL LANDSCAPE ...... p.15 III: LAND USE AND LANDSCAPE CHANGE .................... p.47 IV: ADVANCING SETTLEMENT, RETREATING WILDLIFE ........ p.95 V: CONSERVATION AND CONTROL ........................ p.129 VI: CONCLUSION ........................................ p.160 BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................ p.165 i ############################################## LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure i. Map of the Zuurveld ............................... p.10 Figure ii. Representation of a Bushman elephant hunt ........... p.99 Figure iii: Representation of a colonial elephant hunt ........... p.100 ii ############################################## ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My grateful thanks must go firstly to Professor Paul Maylam. In overseeing -

For Southern Africa SHIPPING ADDRESS: POSTAL ADDRESS: Clo HARVARD EPWORTH CHURCH P

International Defense and Aid Fund for Southern Africa SHIPPING ADDRESS: POSTAL ADDRESS: clo HARVARD EPWORTH CHURCH P. 0. Box 17 1555 MASSACHUSETfS AYE. CAMBRIDGE. MA 02138 CAMBRIDGE. MA 02138 TEL (617) 491-8343 BOARD OF TRUSTEES A LETTER FROM DONALD WOODS Willard Johnson, President Margaret Burnham Kenneth N. Carstens John B. Coburn Dear Friend, Jerry Dunfey Richard A. Falk You can save a life ~n South Africa. EXECUTIVE DIRECIDR Kenneth N. E:arstens ..:yOtl- e-an-he-l--p -ave-a h-i-l cl adul-t ~rom the herre-I"s- af a South African prison cell. ASSISTANT DIRECIDR Geoffrey B. Wisner You can do this--and much more--by supporting the SPONSORS International Defense and Aid Fund for Southern Africa--IDAF. John C. Bennett Lerone Bennett, Jr. Leonard Bernstein How do I know this? Mary F. Berry Edward W. Brooke I have seen the many ways in which IDAF defends political Robert McAfee Brown prisoners and their families in Southern Africa. Indeed, Shirley Chisholm I myself helped to deliver the vital services it provides. Dorothy Cotton Harvey Cox C. Edward Crowther You can be sure that repression in South Africa will not Ronald V. DeHums end until freedom has been won. That means more brutality Ralph E. Dodge by the South African Police--more interrogations, more torture, Gordon Fairweather more beatings, and even more deaths. Frances T. Farenthold Richard G. Hatcher Dorothy 1. Height IDAF is one of the most effective organizations now Barbara Jordan working to protect those who are imprisoned and brutally Kay Macpherson ill-treated because of their belief in a free South Africa. -

Early History of South Africa

THE EARLY HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES . .3 SOUTH AFRICA: THE EARLY INHABITANTS . .5 THE KHOISAN . .6 The San (Bushmen) . .6 The Khoikhoi (Hottentots) . .8 BLACK SETTLEMENT . .9 THE NGUNI . .9 The Xhosa . .10 The Zulu . .11 The Ndebele . .12 The Swazi . .13 THE SOTHO . .13 The Western Sotho . .14 The Southern Sotho . .14 The Northern Sotho (Bapedi) . .14 THE VENDA . .15 THE MASHANGANA-TSONGA . .15 THE MFECANE/DIFAQANE (Total war) Dingiswayo . .16 Shaka . .16 Dingane . .18 Mzilikazi . .19 Soshangane . .20 Mmantatise . .21 Sikonyela . .21 Moshweshwe . .22 Consequences of the Mfecane/Difaqane . .23 Page 1 EUROPEAN INTERESTS The Portuguese . .24 The British . .24 The Dutch . .25 The French . .25 THE SLAVES . .22 THE TREKBOERS (MIGRATING FARMERS) . .27 EUROPEAN OCCUPATIONS OF THE CAPE British Occupation (1795 - 1803) . .29 Batavian rule 1803 - 1806 . .29 Second British Occupation: 1806 . .31 British Governors . .32 Slagtersnek Rebellion . .32 The British Settlers 1820 . .32 THE GREAT TREK Causes of the Great Trek . .34 Different Trek groups . .35 Trichardt and Van Rensburg . .35 Andries Hendrik Potgieter . .35 Gerrit Maritz . .36 Piet Retief . .36 Piet Uys . .36 Voortrekkers in Zululand and Natal . .37 Voortrekker settlement in the Transvaal . .38 Voortrekker settlement in the Orange Free State . .39 THE DISCOVERY OF DIAMONDS AND GOLD . .41 Page 2 EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES Humankind had its earliest origins in Africa The introduction of iron changed the African and the story of life in South Africa has continent irrevocably and was a large step proven to be a micro-study of life on the forwards in the development of the people. -

The Cape Supergroup in Natal and the Northern Transkei

485 The Cape Supergroup in Natal and the Northern Transkei SIR,—The rocks of the so-called Cape System (Cape Supergroup) of South Africa outcrop in two coastal belts, separated by 300 km of younger rocks (see map). In Cape Province, a full succession has been described (see Table 1), extending frorn possible Lower Cambrian to Upper Devonian. The Natal sequence is incomplete, and consists of 'thick . sandstones, with grits and conglomerates' (Anderson, 1901), resting on Precambrian rocks and overlain by Karroo strata. In his First Report of the Geological Survey of Natal and Zulu/and, Anderson (1901) observed that: 'Petrologically, they are very unlike the quartzites and grits of the Table Mountain Sandstones of Cape Colony.' In his Second Report, however, Anderson (1904) concluded: '... I think that there is no doubt as to the correlation of the formation spoken of in my first report as "Palaeozoic Sandstones", with the Table Mountain Sandstones of Cape Colony'. No palaeontological evidence existed to confirm or disprove this identification, but subsequent authors have accepted Anderson's conclusions, and reference to the 'Table Mountain Sandstones of Natal' is encountered commonly. Late in 1970, a few poorly preserved fossils were found by quarry workers at a locality about 5 km W of Port St Johns, in Pondoland. Originally thought to be fish, they were sent to Grahamstown, where they were identified as protolycopods. Similar lycopsids are known from the upper parts of the Bokkeveld Group, and from the Witteberg Group. Although rare lycopsids have been recorded from the Early Devonian, the class did not become abundant until later in the period; it is thus improbable that any strata containing lycopsids are correlatives of the pre-Devonian Table Mountain Group. -

Cry Freedom Essay

L.B. History Period 7 Feb. 2003 Cry Freedom; Accurate? Have you ever seen a movie based on a true story and wondered if it was truly and completely accurate? Many movies and books documenting historical lives and events have twisted plots to make the story more interesting. The movie Cry Freedom, directed by Richard Attenborough, is not one of these movies; it demonstrates apartheid in South Africa accurately through the events in the lives of both Steve Biko and Donald Woods. Cry Freedom has a direct relation to black history month, and has been an influence to me in my feelings about racism and how it is viewed and dealt with today. Cry Freedom was successful in its quest to depict Steve Biko, Donald Woods, and other important characters as they were in real life. Steve Biko was a man who believed in justice and equality for all races and cultures. The important points in his life such as his banning (1973), his famous speeches and acts to influence Africans, the trial (convicting the nine other black consciousness leaders) in which he took part, his imprisoning and ultimately his death were documented in Cry Freedom, and they were documented accurately. Steve Biko was banned by the South African Apartheid government in 1973. Biko was restricted to his home in Kings William's Town in the Eastern Cape and could only converse with one person at a time, not including his family (The History Net, African History http://africanhistory.about.com/library/biographies/blbio-stevebiko.htm). In the movie, this is shown when Biko first meets Donald Woods where he explains his banning situation. -

December 2009 Is Passed on Only Through the Male Line

Volume 36 Number 1 December 2009 is passed on only through the male line. The only source of variation among mtDNA types is mutation, and the number of mutations separating two mtDNA types is a direct measure of the length of time since they shared a common ancestor. Since women do not carry Y-chromosomes, they can only be tested for mtDNA, but men can be tested for both types. Occasionally some of the genes carried by the DNA types mutate and the resultant genetic changes are passed on to future generations. The mapping of these mutations allows geneticists to track the history of various population groups. This has enabled researchers to determine that the most recent common ancestor of all modern humans on the maternal side Reports covering the period February to June 2009 lived some 150 000 years ago, while that on the paternal side dates to somewhere between 60 000 and 80 000 years ago. Prof. Soodyall then provided information on three facets of her work. The first is of a scientific nature and involves mapping the genetic codes of populations around the globe, but in particular in sub-Saharan Africa and the Indian Ocean islands, and especially those groups that have lived in relative isolation in a particular region over a long period of time. The second aspect of her studies revolves around three burning questions: 1. Is it possible to localise the most likely regions for the origins of various lineages? EVENING LECTURES 2. What impact did trade, which had occurred for well over 2 000 years in the Indian Ocean, have on population groups? 3. -

Biko Met I Must Say, He Nontsikelelo (Ntsiki) Mashalaba

LOVE AND MARRIAGE In Durban in early 1970, Biko met I must say, he Nontsikelelo (Ntsiki) Mashalaba Steve Biko Foundation was very politically who came from Umthatha in the Transkei. She was pursuing involved then as her nursing training at King Edward Hospital while Biko was president of SASO. a medical student at the I remember we University of Natal. used to make appointments and if he does come he says, “Take me to the station – I’ve Daily Dispatch got a meeting in Johannesburg tomorrow”. So I happened to know him that way, and somehow I fell for him. Ntsiki Biko Daily Dispatch During his years at Ntsiki and Steve university in Natal, Steve had two sons together, became very close to his eldest Nkosinathi (left) and sister, Bukelwa, who was a student Samora (right) pictured nurse at King Edward Hospital. here with Bandi. Though Bukelwa was homesick In all Biko had four and wanted to return to the Eastern children — Nkosinathi, Cape, she expresses concern Samora, Hlumelo about leaving Steve in Natal and Motlatsi. in this letter to her mother in1967: He used to say to his friends, “Meet my lady ... she is the actual embodiment of blackness - black is beautiful”. Ntsiki Biko Daily Dispatch AN ATTITUDE OF MIND, A WAY OF LIFE SASO spread like wildfire through the black campuses. It was not long before the organisation became the most formidable political force on black campuses across the country and beyond. SASO encouraged black students to see themselves as black before they saw themselves as students. SASO saw itself Harry Nengwekhulu was the SRC president at as part of the black the University of the North liberation movement (Turfloop) during the late before it saw itself as a Bailey’s African History Archive 1960s. -

Black Power, Black Consciousness, and South Africa's Armed Struggle

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) Graduate Dissertations and Theses Dissertations, Theses and Capstones 6-2018 UNCOVERING HIDDEN FRONTS OF AFRICA’S LIBERATION STRUGGLE: BLACK POWER, BLACK CONSCIOUSNESS, AND SOUTH AFRICA’S ARMED STRUGGLE, 1967-1985 Toivo Tukongeni Paul Wilson Asheeke Binghamton University--SUNY, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/dissertation_and_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Asheeke, Toivo Tukongeni Paul Wilson, "UNCOVERING HIDDEN FRONTS OF AFRICA’S LIBERATION STRUGGLE: BLACK POWER, BLACK CONSCIOUSNESS, AND SOUTH AFRICA’S ARMED STRUGGLE, 1967-1985" (2018). Graduate Dissertations and Theses. 78. https://orb.binghamton.edu/dissertation_and_theses/78 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations, Theses and Capstones at The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNCOVERING HIDDEN FRONTS OF AFRICA’S LIBERATION STRUGGLE: BLACK POWER, BLACK CONSCIOUSNESS, AND SOUTH AFRICA’S ARMED STRUGGLE, 1967-1985 BY TOIVO TUKONGENI PAUL WILSON ASHEEKE BA, Earlham College, 2010 MA, Binghamton University, 2014 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the Graduate School of Binghamton University State University of New -

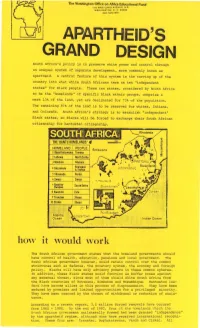

Apartheid's Grand Design

The Washington Office on Africa Educational Fund 110 MARYLAND AVENUE. N .E. WASHINGTON. 0. C. 20002 (202) 546-7961 APARTHEID'S GRAND DESIGN South Africa's policy is to preserve white power and control through an unequal system of separate development, more commonly known as apartheid. A central feature of this system is the carving up of the country into what white South Africans term as ten "independent states" for Black people. These ten states, considered by South Africa to be the "homelands" of specific Black ethnic groups, comprise a mere 13% of the land, yet are designated for 73% of the population. The remaining 87% of the land is to be reserved for whites, Indians, and Coloreds. South Africa's strategy is to establish "independent" Black states, so Blacks will be forced to exchange their South African citizenship for bantustan citizenship. THE 'BANTU HOMELANDS' 4 HOMELAND I PEOPLE I Boputhatswanai Tswana 2 lebowa I North Sotho -~ Hdebete Ndebe!e 0 Shangaan Joh<tnnesourg ~ Gazankulu & Tsonga 5 Vhavenda Venda --~------l _ ______6 Swazi 1 1 ___Swazi_ _ _ '7 Basotho . Qwaqwa South Sotho 8 Kwazulu 9 Transkei 10 Ciskei It• vvould w-ork The South African government states that the homeland governments should have control of health, education, pensions and local government. The South African government however, would retain control over t h e common structures such as defense, the monetary s y stem, the economy and foreign policy . Blacks wi ll have only advisory powers in these common spheres. In addition, these Black states would function as buffer zones against any external threat, since most of them shield white South Africa from the Black countries of Botswana, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. -

Title: Black Consciousness in South Africa : the Dialectics of Ideological

Black Consciousness in South Africa : The Dialectics of Ideological Resistance to White title: Supremacy SUNY Series in African Politics and Society author: Fatton, Robert. publisher: State University of New York Press isbn10 | asin: 088706129X print isbn13: 9780887061295 ebook isbn13: 9780585056890 language: English Blacks--South Africa--Politics and government, Blacks--Race identity--South Africa, South Africa-- Politics and government--1961-1978, South subject Africa--Politics and government--1978- , South Africa--Social conditions--1961- , Blacks--South Africa--Social cond publication date: 1986 lcc: DT763.6.F37 1986eb ddc: 305.8/00968 Blacks--South Africa--Politics and government, Blacks--Race identity--South Africa, South Africa-- Politics and government--1961-1978, South subject: Africa--Politics and government--1978- , South Africa--Social conditions--1961- , Blacks--South Africa--Social cond Page i Black Consciousness in South Africa Page ii SUNY Series in African Politics and Society Henry L. Bretton and James Turner, Editors Page iii Black Consciousness in South Africa The Dialectics of Ideological Resistance to White Supremacy Robert Fatton Jr. State University of New York Press Page iv Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 1986 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address State University of New York Press, State University Plaza, Albany, N.Y., 12246 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Fatton, Robert. Black consciousness in South Africa. (SUNY series in African politics and society) Revision of the author's thesis (Ph.D)University of Notre Dame. -

Trade and Interaction on the Eastern Cape Frontier: an Historical Archaeological Study of the Xhosa and the British During the Early Nineteenth Century

TRADE AND INTERACTION ON THE EASTERN CAPE FRONTIER: AN HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDY OF THE XHOSA AND THE BRITISH DURING THE EARLY NINETEENTH CENTURY 0.i\ By. FLORDELIZ T BUGARIN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2002 Copyright 2002 by Flordeliz T. Bugarin This is dedicated to Cris Bugarin, my mom. Tern Bugarin, my father, and Marie Bugarin, my sister. Thank you for being the family that supports me. Also, this is in memory of my Uncle Jack who died while I was in South Africa. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Researching and writing this dissertation gave me an incredible chance to meet some generous, warm, and intelligent people. From South Africa to California to Florida, I have met people who challenged me, motivated me, and supported me. To them, I offer my heartfelt thanks. My advisor, longtime teacher, and good friend, Peter Schmidt, gave me unending support, faith in my abilities, encouragement when I had doubt, and advice when I needed direction I appreciate the many hours he set aside to advise me, seriously consider my ideas no matter how esoteric, and shape the development of my writing • skills. I thank him for pulling together my committee when I needed them and for choosing a cohort of students who will be my close, life long colleagues. I am very gratefiil for the opportunity to work with Hunt Davis. His enthusiasm, warm nature, and love for South Africa gave me inspiration and encouragement. -

Druckversion

RESEEN Jakob Skovgaard ›TO MAKE A STATEMENT‹ The Representation of Black Consciousness in Richard Attenborough’s Cry Freedom (1987) Cry Freedom (United Kingdom, 1987), 157 min., director and producer: Richard Attenborough, screenplay: John Briley (based on books by Donald Woods), music: George Fenton/Jonas Gwangwa, camera: Ronnie Tailor, cast: Denzel Washington, Juanita Waterman, Kevin Kline et al. As one of the most viewed films on apartheid South Africa, Sir Richard Attenborough’s Oscar-nominated Cry Freedom helped push the atrocities of the apartheid system to the forefront of public attention. The screenplay was based on South African journalist Donald Woods’ autobiographical books Biko (1978) and Asking for Trouble (1981), which detail Woods’ relationship with Biko and the court trial following Biko’s death in police custody. The plot runs as follows: despite being the editor of a liberal newspaper, Woods is initially dismissive of the ideas and methods of the Black Consciousness Movement, believing that it advocates racism towards white people. He soon changes his mind, however, when he learns more about Biko’s philosophy, and the two become close Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History 13 (2016), S. 372-377 © Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen 2016 | ISSN 1612-6033 (Print), 1612-6041 (Online) ›TO MAKE A STATEMENT‹ 373 friends. Due to his function as de facto leader of the Black Consciousness Movement, Biko is harassed and put under observation by the South African authorities; half- way through the film, he is arrested and dies in police custody. The last part of the film portrays how Woods and his family plan and finally manage to escape from South Africa.