Cessnock RSL Sub-Branch | 49914141 Volume 1 Issue 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arms and Machine Guns from the Year 1863 up to the Present Day

Royal United Services Institution. Journal ISSN: 0035-9289 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rusi19 Personal Reminiscences of the Evolution of Small- Arms and Machine Guns from the Year 1863 up to the Present Day Lieut.-Colonel W. N. Lockyer Chief Inspector of Small-Arms R.A. To cite this article: Lieut.-Colonel W. N. Lockyer Chief Inspector of Small-Arms R.A. (1898) Personal Reminiscences of the Evolution of Small-Arms and Machine Guns from the Year 1863 up to the Present Day, Royal United Services Institution. Journal, 42:248, 1121-1151, DOI: 10.1080/03071849809417413 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03071849809417413 Published online: 11 Sep 2009. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 6 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rusi20 Download by: [The University Of Melbourne Libraries] Date: 17 June 2016, At: 12:25 VOL. XLII. [Aiithors aZotie are responsi6Ze for fhe contenfs of fheir respectizfe PGpers.3 PERSONAL REMINISCENCES OF THE EVOLU- TION OF SAIALL-ARkIS AND RIACHINE GUNS FROhI. .THE YEAR lSG3 UP 'I'O THE PRESENT DAY. By Lictrt.-CoZonrl ll! AT. LOCKYER, R.A., Chief Irrsprctorof SnioZZ-Arm. Wednesday, June 20th, ISDS. Rear-Admiral the Rt. Ron. Lord CHARLESBEIZESFOKD, C.B., N.P., in the Chair. I.-RIFLES, ETC. I MAKE the year 18G3 the starting point for two reasons :- 1. Because it was just the close of the muzzle-loading pcriod. 2. Because it was in that year that I became personally acquainted with the Service rifle, since which time I have continually kept up my acquaintancewith thcService small-arms, making all kinds of experirncnts; and for the last sixteen years my duty has been to inspect and tcst the various arms during their mannractnre, after they are finished before issue, and again when in use in the hands of the troops. -

The Martini Henry 2

The Journal of the Historical Breechloading Smallarms Association Volume 4, No. 8 ISSN: 0305-0440 © 2016 The Historical Breechloading Smallarms Association, BCM HBSA, London WC1N 3XX The cover picture A sketch of the action of the original type of Gehendra rifle made by John Walter during research for the book: “Guns of the Gurkhas”. Advice to authors he HBSA Journal is published annually and welcomes contributions on topics concerning Tbreechloading arms from the 18th century onwards, covering developments in smallarms technology, ammunition, sights and accoutrements. Short articles of a few hundred words can be published, and major works should not normally exceed 12,000 words. Manuscripts should be sent to the editor electronically, with text and illustrations separately. Permission should be obtained from any copyright holder of illustrations and such permission should be acknowledged in the article. References should be listed at the end of the article using the Havard referencing style: http://goo.gl/CBDmp. Articles are subject to peer-review and may be edited with the author’s agreement. Authors are requested to contact the editor ([email protected]) before submitting a manuscript. Layout and Artwork David Butterworth Tel 020 8816 8472, [email protected] www.davidbutterworth.co.uk Print Print Impressions Ltd. Unit 18, West Station Industrial Estate, Maldon, Essex CM9 6TW Tel 016 2192 8083 Historical Breechloading Smallarms Association Volume 4, Number 8 November 2016 Patron: Commander The Lord Cottesloe KStJ JP -

Maxim Silencer Company Photographs 2015.288

Maxim Silencer Company photographs 2015.288 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Audiovisual Collections PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Maxim Silencer Company photographs 2015.288 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Maxim Silencer Company photographs 2015.288 Summary Information Repository: -

Mg 34 and Mg 42 Machine Guns

MG 34 AND MG 42 MACHINE GUNS CHRIS MC NAB © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com MG 34 AND MG 42 MACHINE GUNS CHRIS McNAB Series Editor Martin Pegler © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 DEVELOPMENT 8 The ‘universal’ machine gun USE 27 Flexible firepower IMPACT 62 ‘Hitler’s buzzsaw’ CONCLUSION 74 GLOSSARY 77 BIBLIOGRAPHY & FURTHER READING 78 INDEX 80 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com INTRODUCTION Although in war all enemy weapons are potential sources of fear, some seem to have a deeper grip on the imagination than others. The AK-47, for example, is actually no more lethal than most other small arms in its class, but popular notoriety and Hollywood representations tend to credit it with superior power and lethality. Similarly, the bayonet actually killed relatively few men in World War I, but the sheer thought of an enraged foe bearing down on you with more than 30cm of sharpened steel was the stuff of nightmares to both sides. In some cases, however, fear has been perfectly justified. During both world wars, for example, artillery caused between 59 and 80 per cent of all casualties (depending on your source), and hence took a justifiable top slot in surveys of most feared tools of violence. The subjects of this book – the MG 34 and MG 42, plus derivatives – are interesting case studies within the scale of soldiers’ fears. Regarding the latter weapon, a US wartime information movie once declared that the gun’s ‘bark was worse than its bite’, no doubt a well-intentioned comment intended to reduce mounting concern among US troops about the firepower of this astonishing gun. -

THE ANGLO-BOER WAR, South African History and Related Subjects (Part I)

Christison Rare Books CATALOGUE 36 The Collection of R. de R. Jooste THE ANGLO-BOER WAR, South African History and Related Subjects (Part I) Dr Tielman Jooste exemplifies the very best attributes of book collectors. Inheriting from his father an interest in the Anglo-Boer War, he sought to discover all he could about the ‘Last of the Gentlemen’s Wars’ and its antecedents. On his maternal De Villiers side, Dr Jooste’s forebears entertained the Boer leaders in their Cape Town home following the War. The family also extended hospitality to such Boer sympathisers as Roger Casement and Alice Stopford Green. However, in his thirst for the truth about what happened, Dr Jooste did not satisfy himself with a collection presenting only one version of events. His wide-ranging library is particularly strong in rare Republican accounts, but there are hundreds of books from the other side of the conflict. Ask the doctor about any book in his collection, and he will be able to offer you an opinion on its merits. He eschews jingoism, and can inevitably see both sides of a matter. In his company, one is reminded of the reception afforded Rayne Kruger’s Good- bye Dolly Gray upon its release, when the author was praised for “a lack of bias in handling a subject still controversial … years after the event.” Given his medical background, it is understandable that Dr Jooste has also focused much on the treatment of the sick and wounded between 1899 and 1902. He has become something of an authority on the subject. -

BRITISH MILITARY WEAPONS the Problem of Telling Their Story in a New Museum by William Reid

Reprinted from the American Society of Arms Collectors Bulletin 33:35-52 Additional articles available at http://americansocietyofarmscollectors.org/resources/articles/ BRITISH MILITARY WEAPONS The Problem of Telling Their Story in a New Museum by William Reid Five years and five months ago, less a few days, I left the Armouries in the Tower o.f London where I worked for 13 years. From the oldest military museum in the world - the Tower was first opened to the public 400 years ago - I moved four miles west to the newest, to become the director of the National Army Museum. The museum began its existence in 1960 in the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, our equivalent of West Point. When I took over as its director in 1970 we had a new building (figure 1) in which to install a modern display telling the history of the British Army from the end of the Middle Ages up massive expansion in two World Wars, to imperial to today. To guide us our charter, signed by the withdrawal and today's relatively small Queen, defines the Army as '. including Britain's establishment. standing army, militia, yeomanry, volunteers, In addition to the temporal range of our subject Territorial Army and Territorial Army and we are also concerned with a vast geographical Volunteer Reserve; and the Indian Army up to sweep. This is a major problem for curator-s and Partition in 1947, the forces of the East India designers alike as the British Army raised its units Company and all other land forces of the Crown.' throughout the empire, incuding Jamaica, where The complexity of this task is all too apparent we bought slaves in 1801 for recruitment into our when the number and variety of these forces is West Indian regiments. -

Inventory of the Henry M. Stanley Archives Revised Edition - 2005

Inventory of the Henry M. Stanley Archives Revised Edition - 2005 Peter Daerden Maurits Wynants Royal Museum for Central Africa Tervuren Contents Foreword 7 List of abbrevations 10 P A R T O N E : H E N R Y M O R T O N S T A N L E Y 11 JOURNALS AND NOTEBOOKS 11 1. Early travels, 1867-70 11 2. The Search for Livingstone, 1871-2 12 3. The Anglo-American Expedition, 1874-7 13 3.1. Journals and Diaries 13 3.2. Surveying Notebooks 14 3.3. Copy-books 15 4. The Congo Free State, 1878-85 16 4.1. Journals 16 4.2. Letter-books 17 5. The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition, 1886-90 19 5.1. Autograph journals 19 5.2. Letter book 20 5.3. Journals of Stanley’s Officers 21 6. Miscellaneous and Later Journals 22 CORRESPONDENCE 26 1. Relatives 26 1.1. Family 26 1.2. Schoolmates 27 1.3. “Claimants” 28 1 1.4. American acquaintances 29 2. Personal letters 30 2.1. Annie Ward 30 2.2. Virginia Ambella 30 2.3. Katie Roberts 30 2.4. Alice Pike 30 2.5. Dorothy Tennant 30 2.6. Relatives of Dorothy Tennant 49 2.6.1. Gertrude Tennant 49 2.6.2. Charles Coombe Tennant 50 2.6.3. Myers family 50 2.6.4. Other 52 3. Lewis Hulse Noe and William Harlow Cook 52 3.1. Lewis Hulse Noe 52 3.2. William Harlow Cook 52 4. David Livingstone and his family 53 4.1. David Livingstone 53 4.2. -

The Wolf That Never Sleeps’

THE BADEN-POWELL STORY — ‘THE WOLF THAT NEVER SLEEPS’ 1 THE BADEN-POWELL STORY — ‘THE WOLF THAT NEVER SLEEPS’ Downloaded from: “The Dump” at Scoutscan.com http://www.thedump.scoutscan.com/ Editor’s Note: The reader is reminded that these texts have been written a long time ago. Consequently, they may use some terms or use expressions which were current at the time, regardless of what we may think of them at the beginning of the 21st century. For reasons of historical accuracy they have been preserved in their original form. If you find them offensive, we ask you to please delete this file from your system. This and other traditional Scouting texts may be downloaded from the Dump. 2 THE BADEN-POWELL STORY — ‘THE WOLF THAT NEVER SLEEPS’ THE STORY OF BADEN-POWELL ‘The Wolf that never Sleeps’ BY HAROLD BEGBIE WITH ILLUSTRATIONS Vestigia nulla retrorsum Originally Published LONDON GRANT RICHARDS 1900 G “... A name and an example, which are at this hour inspiring hundreds of the youth of England....” Southey’s Life of Nelson. First printed May 1900. Reprinted May 1900. 3 THE BADEN-POWELL STORY — ‘THE WOLF THAT NEVER SLEEPS’ MAJOR-GENERAL R.S.S. BADEN-POWELL. 4 THE BADEN-POWELL STORY — ‘THE WOLF THAT NEVER SLEEPS’ To SMITH MAJOR HONOURED SIR, If amid the storm and stress of your academic career you find an hour’s relaxation in perusing the pages of this book, all the travail that I have suffered in the making of it will be repaid a thousandfold. Throughout the quiet hours of many nights, when Morpheus has mercifully muzzled my youngest (a fine child, sir, but a female), I have bent over my littered desk driving a jibbing pen, comforted and encouraged simply and solely by the vision of my labour’s object and attainment. -

450 Maxim Machine Gun (Martini Henry Chamber)” Water Cooled Machine Gun; Introduced in NZ Service: 1896 Withdrawn: After 1901 When Converted to .303

NZART ID: 375, Arm Type: Machine Gun, Date of Draft: (V1) 13 June 2014, Compiled by: Phil Cregeen Pattern: “.450 Maxim Machine Gun (Martini Henry chamber)” water cooled Machine Gun; Introduced in NZ Service: 1896 Withdrawn: after 1901 when converted to .303. Makers: Maxim Nordenfelt Guns & Ammunition Co Ltd, Crayford Works, UK; Calibre: .450”, Bore: 7 groove RH twist 1 in 20” Henry rifling, Barrel length: 28.5 in. OA Length: 42.4 in. Weight: 60 Lb bare, Type of Action: Short recoil full auto; Cyclic rate: 400-500 rpm; Magazine: 250 round fabric belt. Sights: Tangent aperture sight graduated to 1000 yds.; Ammo: .450 Martini Henry Originally .45 Maxim later converted to .303 No 5700 mounted on Mk IV tripod at National Army Museum, Waiouru The Maxim gun was the first recoil-operated machine gun, invented by Sir Hiram Stevens Maxim in 1884. Maxim established the Maxim Gun Company with financing from Albert Vickers, son of steel entrepreneur Edward Vickers. Albert Vickers became the company's chairman, and it later joined hands with a Swedish competitor, Nordenfelt, to become Maxim Nordenfelt Guns and Ammunition Company. Finally, the company was absorbed into the Vickers company, leading first to the Maxim-Vickers gun and then, after Vickers' redesign, the Vickers machine gun. Maxim guns were initially adopted for British Land Service in 1888, in .577/.450 calibre, .45 Maxim machine gun (M-H chamber), but in 1893 a .303 version was introduced and many of the earlier .450 guns were converted to .303, .303 Converted Maxim machine gun (magazine rifle chamber). -

Atkinson Correspondence: Research Notes

ATKINSON CORRESPONDENCE Research notes 1 A number of examples of correspondence from Lance Corporal W A Atkinson (G Troop) have appeared on the philatelic market (2008).First stationed at Macloutsie, and later at Fort Gaberones, he received mail from East London each addressed in the same handwriting. Peter Thy writes: "Three typical examples are shown here, all franked with 2d and cancelled with hooted or regular Port Elizabeth dated cancellers. The cover addressed to Macloutsie received transit marks at Fourteen Streams, Vryburg, and Mafeking and a receiving mark at Macloutsie and this provide excellent information on mail route and schedules. Many of the covers were taxed at 2d or 4d and may record a 1892 rate change in the Cape for early Bechuanaland Protectorate mail". The following notes are in support of future research relating thereto. BECHUANALAND BORDER POLICE (BBP) was an Imperial unit raised on 4 August 1885 by then Lt. Col. Frederick Carrington 1 of the South Wales Borderers, with a strength of 500 men. Their weaponry included Martini-Henry rifles equipped with a bayonets and Maxim automatic machine guns. 1 Born Cheltenham, England 23rd August 1844; died Cheltenham 22 March 1913. 2 In 1887, Frank William Frederick Johnson with Maurice Heany and Henry Borrow (ex- members of the BBP) organized a group known as the Northern Gold Fields Exploration syndicate which won a concession from Chief Khama covering all mineral rights in Bechuanaland. In 1889, Johnson met Cecil John Rhodes in Kimberley. He was awarded a contract to organize, equip and lead the Pioneer Corps, a group of circa two hundred-odd men whose goal it was to occupy Mashonaland, build a road between Palapye and Mount Hampden (later Fort Salisbury) and essentially prepare the way for colonization and exploitation of the concession 2. -

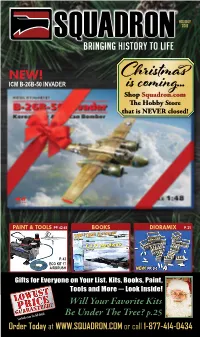

Aviation Modelling at Squadron.Com 1:144 SCALE — MINICRAFT

HOLIDAY 2019 BRINGING HISTORY TO LIFE NEW! ICM B-26B-50 INVADER Christmas Shopis coming... Squadron.com The Hobby Store that is NEVER closed! PAINT & TOOLS PP. 42-45 BOOKS DIORAMIX P. 31 P. 42 ECO KIT 17 AIRBRUSH NEW! PP. 2-3 Gifts for Everyone on Your List. Kits, Books, Paint, Tools and More — Look Inside! Will Your Favorite Kits Be Under The Tree? p.25 See back cover for full details. Order Today at WWW.SQUADRON.COM or call 1-877-414-0434 IT’S NEVER TO EARLY for Christmas Shopping Dear Friends, I cannot believe it is November! This time of year is one of reflection; so many things to be thankful for. It is very fitting that this season of thanks begins with Veteran’s Day. I speak for the entire team here at Squadron when I say there are not enough words to thank you all who have served our great country in any capacity. Your courage and sacrifice protect the freedom we all enjoy. We are in your debt. Keeping history alive is one of the roles we embrace here at Squadron. One of the easiest ways to do that is to visit our book pages in the flyer (pp.16-19 aviation, pp. 33-35 armor, p. 37 ships and p. 24 magazines). Back in stock again is another Squadron Signal favorite – SS10225 Avenger in Action by David Doyle (seen below). Don’t miss it, along with thousands of titles we feature on Squadron.com from Casemate, Ginter, Schiffer, Kagero, Classic Warships, and much more. -

American and German Machine Guns Used in WWI

John Frederick Andrews Novels of the Great War American and German Machine Guns Used in WWI The machine gun changed the face of warfare in WWI. The devastating effects of well-emplaced machine guns against infantry and cavalry became brutally evident in the 1st World War. It changed infantry tactics forever. The US Marines and Army had several machine guns available during the war. This brief will discuss crew-served machine guns only. Man-portable automatic rifles are discussed in another article. The Lewis gun is mentioned here for completeness. The Marine 1st Machine Gun Battalion, commanded by Maj. Edward Cole trained with the Lewis gun before shipping overseas. The gun had been used by the British with good effect. Cole’s men trained with at the Lewis facility in New York. At that point, the plan was for each company to have an eight-gun machine gun platoon. A critical shortage in the aviation community stripped the Marines of their Lewis guns before they shipped to France. The Lewis Gun weighed 28 pounds and was chambered in the .303 British, .30.06 Springfield, and 7.92x57 mm Mauser. They were fed by a top-mounted magazine that could hold 47 or 96 rounds. Rate of fire was 500-600 rounds per minute with a muzzle velocity of 2,440 feet per second and an effective range of 880 yards and a maximum of 3,500 yards. The infantry model is shown below. John Frederick Andrews Novels of the Great War When the Lewis guns were taken away, the Hotchkiss Model 1914 was issued in its place.