Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Publics to See the Full List of the Publics, Read Appendix a on a Later

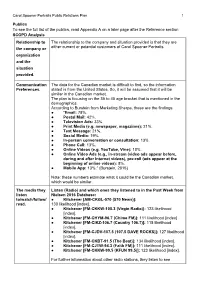

Carol Spooner Portraits Public Relations Plan 1 Publics To see the full list of the publics, read Appendix A on a later page after the Reference section SCOPD Analysis Relationship to The relationship to the company and situation provided is that they are the company or either current or potential customers of Carol Spooner Portraits. organization and the situation provided. Communication The data for the Canadian market is difficult to find, so the information Preferences. stated is from the United States. So, it will be assumed that it will be similar in the Canadian market. The plan is focusing on the 35 to 45 age bracket that is mentioned in the demographics. According to Burstein from Marketing Sherpa, these are the findings: ● “Email: 78%. ● Postal Mail: 42%. ● Television Ads: 33%. ● Print Media (e.g. newspaper, magazines): 21%. ● Text Message: 21%. ● Social Media: 19%. ● In-person conversation or consultation: 13%. ● Phone Call: 13%. ● Online Videos (e.g. YouTube, Vine): 10%. ● Online Video Ads (e.g., in-stream (video ads appear before, during and after Internet videos), pre-roll (ads appear at the beginning of online videos): 8%. ● Mobile App: 13%.” (Burstein, 2015) Note: these numbers estimate what it could be the Canadian market, which would be similar. The media they Listen (Radio) and which ones they listened to in the Past Week from listen Nielsen 2016 Database: to/watch/follow/ ● Kitchener [AM-CKGL-570 (570 News)]: read. 130 likelihood [index]. ● Kitchener [FM-CKKW-105.3 (Virgin Radio)]: 123 likelihood [index]. ● Kitchener [FM-CHYM-96.7 (Chime FM)]: 111 likelihood [index] ● Kitchener [FM-CIKZ-106.7 (Country 106.7)]: 115 likelihood [index]. -

CTV News | Where Canada Shines: Water Tech 11-06-22 11:41 AM

CTV News | Where Canada shines: water tech 11-06-22 11:41 AM CTV.ca Mobile Canada AM Autos Entertainment Olympics Contests Local Stations Shows Video News Schedule News Sections Home : Business Top Stories Canada Where Canada shines: water tech World GRANT BUCKLER - The Globe and Mail Entertainment According to the World Health Organization, more than 3.5 million people die each year Sports from water-related diseases worldwide. But clean water is a problem Canadian technologies can help solve. This country has a significant number of companies Business providing technology for cleaning water, either before it is used for drinking or before it returns to the environment after use in households or industry. Sci-Tech “There is a solid capacity for managing water and water technology in Canada,” says Health Rick Findlay, vice-chair of the Canadian Water Network, a water research group that is Politics part of the Network of Centres of Excellence program. “We do play on the world stage – and we could play a bigger role, of course.” Weather Canada’s strengths in this area didn’t grow because we faced greater challenges – countries such as Israel and Australia are shorter of water than we are. In fact, the News Programs opposite may be partly true. CTV National News Industry grew up around the Great Lakes precisely because of the availability of water, with Lloyd Robertson observes David Henderson, managing director of XPV Capital Corp., which invests in water companies. When legislation started forcing those companies to clean up their Canada AM wastewater, a significant market for water purification resulted, creating what Mr. -

The Joy of Autism: Part 2

However, even autistic individuals who are profoundly disabled eventually gain the ability to communicate effectively, and to learn, and to reason about their behaviour and about effective ways to exercise control over their environment, their unique individual aspects of autism that go beyond the physiology of autism and the source of the profound intrinsic disabilities will come to light. These aspects of autism involve how they think, how they feel, how they express their sensory preferences and aesthetic sensibilities, and how they experience the world around them. Those aspects of individuality must be accorded the same degree of respect and the same validity of meaning as they would be in a non autistic individual rather than be written off, as they all too often are, as the meaningless products of a monolithically bad affliction." Based on these extremes -- the disabling factors and atypical individuality, Phil says, they are more so disabling because society devalues the atypical aspects and fails to accommodate the disabling ones. That my friends, is what we are working towards -- a place where the group we seek to "help," we listen to. We do not get offended when we are corrected by the group. We are the parents. We have a duty to listen because one day, our children may be the same people correcting others tomorrow. In closing, about assumptions, I post the article written by Ann MacDonald a few days ago in the Seattle Post Intelligencer: By ANNE MCDONALD GUEST COLUMNIST Three years ago, a 6-year-old Seattle girl called Ashley, who had severe disabilities, was, at her parents' request, given a medical treatment called "growth attenuation" to prevent her growing. -

Rights Ownership of the Top 100 Tv Programs in Canada (English Channels) According to Ama

Review of the Canadian Communications TELUS Communications Inc. Legislative Framework January 11, 2019 Appendix 6 RIGHTS OWNERSHIP OF THE TOP 100 TV PROGRAMS IN CANADA (ENGLISH CHANNELS) ACCORDING TO AMA By: Mario Mota, Boon Dog Professional Services Inc. For: TELUS November 2017 Review of the Canadian Communications TELUS Communications Inc. Legislative Framework January 11, 2019 Appendix 6 Rights Ownership of the Top 100 TV Programs in Canada (English Channels) According to AMA 2017-2018 Broadcast Year to Date (Aug. 28 - Nov. 19, 2017) This is an analysis of who owns the rights to the Top 100 TV programs that have aired on English- language television channels in Canada according to Average Minute Audience (AMA)1 in the 2017- 2018 broadcast year to date (between August 28, 2017 and November 19, 2017). The list of the Top 100 programs can be found in the table on the pages that follow. It should be noted that duplicate listings (airings) of the same program title (series) have been removed from the list, with the exception of news programs and sporting events. In other words, whereas the program The Big Bang Theory (as an example) would have appeared numerous times in the Top 100 list, only the episode/airing with the highest AMA is included in the list. As can be seen, Canada’s vertically integrated broadcasters combined—Bell Media (CTV, CTV Two, TSN, Space), Corus Entertainment (Global, Treehouse, W Network), and Rogers (Citytv, Sportsnet—dominate the list of Top 100 programs, with Canada’s national public broadcaster, CBC, appearing several times and one U.S. -

December 11, 2012 9:00 A.M

MEDIA RELEASE: Friday, December 7, 2012, 4:30 p.m. REGIONAL MUNICIPALITY OF WATERLOO COMMUNITY SERVICES COMMITTEE AGENDA Tuesday, December 11, 2012 9:00 a.m. Regional Council Chamber 150 Frederick Street, Kitchener 1. DECLARATIONS OF PECUNIARY INTEREST UNDER THE MUNICIPAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST ACT 2. PRESENTATIONS 3. REPORTS – Public Health a) PH-12-050, Compliance with the Ontario Public Health Organizational 1 Standards b) PH-12-051, Infection Prevention and Control Program Report 4 c) PH-12-053, 2012-2013 Influenza Season Update 7 d) CPC-12-004, Friends of Crime Prevention Launch (Staff Presentation) 11 REPORTS – Social Services e) SS-12-053, Centralized Child Care Registration & Waitlist Data Base 13 f) SS-12-054, Children’s Services - Community Collaboration Grants 15 g) SS-12-056, The Region of Waterloo’s Comprehensive Approach to Poverty 19 Reduction (Staff Presentation - Attachment distributed separately to Councillors and Senior Staff only) REPORTS – Planning, Housing & Community Services h) P-12-132, Doors Open Waterloo Region 2012 –Tenth Anniversary 30 4. INFORMATION/CORRESPONDENCE a) Memo: Community Start Up and Maintenance Benefit Study 39 b) Memo: Region of Waterloo Library Service Review Research Results (Colour 82 attachment distributed separately to Councillors and Senior Staff) 5. OTHER BUSINESS a) Council Enquiries and Requests for Information Tracking List 93 1321481 CS Agenda - 2 - 12/12/11 6. NEXT MEETING – January 8, 2013 7. MOTION TO GO INTO CLOSED SESSION THAT a closed meeting of the Community Services and Planning -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

Security Coordinator

STEVE SUMMERVILLE Curriculum Vitae April 2021 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................... 2 Steven Summerville – Contact Information .............................. 3 Professional Background ......................................................... 3 Education ................................................................................ 10 Continuing Education ............................................................. 11 Associations ........................................................................... 16 Awards .................................................................................... 16 Crowd Control Project Management ....................................... 18 Special Events Management................................................... 19 Project Participation ............................................................... 25 Private Consulting .................................................................. 37 Media Presentations ............................................................... 68 Expert Witness Recognition ................................................... 85 April 2021 2 Steven Summerville – Contact Information STAY SAFE Instructional Programs. (SSIP) 3 Holmes Crescent Ajax, Ontario. L1T 3R6 Cell: (416)-318-8299 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Website: https://staysafeip.com/ Professional Background CANADIAN NATIONAL EXHIBITION ASSOCIATION (CNE). – Toronto, Ontario. May 2016 to present Security Coordinator. -

Council Addendum Agenda

Media Release: Tuesday, June 2, 2020, 4:30 p.m. Regional Municipality of Waterloo Addendum Council Agenda Wednesday, June 3, 2020 7:00 p.m. Meeting to be held electronically 1. Moment of Silence 2. Roll Call 3. Declarations of Pecuniary Interest under the “Municipal Conflict Of Interest Act” 4. Presentations 5. Petitions 6. Delegations a) Chuck Howitt, Ink Stained Wretches, re: Supporting Local Journalism proposed resolution https://www.ink-stainedwretches.org/ *Page 6 7. Minutes of Previous Meetings a) Closed Special Council – May 6, 2020 b) Closed Special Council – May 8, 2020 c) Closed Council – May 13, 2020 d) Council – May 13, 2020 e) Closed Committee of the Whole – May 26, 2020 Should you require an alternative format please contact the Regional Clerk at Tel.: 519-575-4400, TTY: 519-575-4605, or [email protected] 3307369 Council Agenda - 2 - 20/06/03 f) *Committee of the Whole – May 26, 2020 g) *Special Council Meeting – June 1, 2020 8. Communications a) Council Information Package – Friday, May 29, 2020 (Distributed Electronically) b) *Letter to Council from Kyle McLeod re: Grand River Transit Electric Buses Page 8 c) *Letter to council from BYD re: Electric Bus Strategy and Pilot Project Page 28 9. Motion To Go Into Committee Of The Whole To Consider Reports 10. Reports Finance Reports a) COR-ADM-20-02, Request for Loan Guarantee from Southwestern Integrated Fibre Technology Incorporated (SWIFT) Page 9 Recommendation: That the Regional Municipality of Waterloo provide to Southwestern Integrated Fibre Technology -

War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada's Military, 1952-1992 by Mallory

War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada’s Military, 19521992 by Mallory Schwartz Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in History Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Mallory Schwartz, Ottawa, Canada, 2014 ii Abstract War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada‘s Military, 19521992 Author: Mallory Schwartz Supervisor: Jeffrey A. Keshen From the earliest days of English-language Canadian Broadcasting Corporation television (CBC-TV), the military has been regularly featured on the news, public affairs, documentary, and drama programs. Little has been done to study these programs, despite calls for more research and many decades of work on the methods for the historical analysis of television. In addressing this gap, this thesis explores: how media representations of the military on CBC-TV (commemorative, history, public affairs and news programs) changed over time; what accounted for those changes; what they revealed about CBC-TV; and what they suggested about the way the military and its relationship with CBC-TV evolved. Through a material culture analysis of 245 programs/series about the Canadian military, veterans and defence issues that aired on CBC-TV over a 40-year period, beginning with its establishment in 1952, this thesis argues that the conditions surrounding each production were affected by a variety of factors, namely: (1) technology; (2) foreign broadcasters; (3) foreign sources of news; (4) the influence -

Council Meeting Agenda Monday, June 22, 2020 Regular Council Meeting Virtual 7:00 P.M

Council Meeting Agenda Monday, June 22, 2020 Regular Council Meeting Virtual 7:00 P.M. This meeting is open to the public and is available through an online platform. Please subscribe to the Township of Wilmot You Tube Channel to watch the live stream or view after the meeting. Delegations must register with the Information and Legislative Services Department. The only matters being discussed at this meeting will be those on the Agenda. 1. MOTION TO CONVENE INTO CLOSED SESSION (IF NECESSARY) 2. MOTION TO RECONVENE IN OPEN SESSION (IF NECESSARY) 3. MOMENT OF SILENCE 4. LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT 5. ADDITIONS TO THE AGENDA 6. DISCLOSURE OF PECUNIARY INTEREST UNDER THE MUNICIPAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST ACT 7. MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETINGS 7.1 Council Meeting Minutes June 8, 2020 RECOMMENDATION THAT the minutes of the following meetings be adopted as presented: Council Meeting June 8, 2020. ***This information is available in accessible formats upon request*** 1 of 68 Council Meeting Agenda June 22, 2020 Page 2 8. PUBLIC MEETINGS 8.1 REPORT NO. DS 2020-006 Zone Change Application 02-20 Jeffrey Van Gyssel 407 Fairview Street, New Hamburg RECOMMENDATION THAT Council approve Zone Change Application 02/20 made by Jeffrey Van Gyssel, affecting 407 Fairview Street, to amend the zoning of the subject property to permit two additional dwelling units within the main residential building on the property. Registered Delegation Jeffrey Van Gyssel 9. PRESENTATIONS/DELEGATIONS 10. CONSENT AGENDA 10.1 REPORT NO. FD 2020-02 First Quarter Activity Report RECOMMENDATION THAT Report No. FD 2020-02 be received for information purposes. -

Vividata Brands by Category

Brand List 1 Table of Contents Television 3-9 Radio/Audio 9-13 Internet 13 Websites/Apps 13-15 Digital Devices/Mobile Phone 15-16 Visit to Union Station, Yonge Dundas 16 Finance 16-20 Personal Care, Health & Beauty Aids 20-28 Cosmetics, Women’s Products 29-30 Automotive 31-35 Travel, Uber, NFL 36-39 Leisure, Restaurants, lotteries 39-41 Real Estate, Home Improvements 41-43 Apparel, Shopping, Retail 43-47 Home Electronics (Video Game Systems & Batteries) 47-48 Groceries 48-54 Candy, Snacks 54-59 Beverages 60-61 Alcohol 61-67 HH Products, Pets 67-70 Children’s Products 70 Note: ($) – These brands are available for analysis at an additional cost. 2 TELEVISION – “Paid” • Extreme Sports Service Provider “$” • Figure Skating • Bell TV • CFL Football-Regular Season • Bell Fibe • CFL Football-Playoffs • Bell Satellite TV • NFL Football-Regular Season • Cogeco • NFL Football-Playoffs • Eastlink • Golf • Rogers • Minor Hockey League • Shaw Cable • NHL Hockey-Regular Season • Shaw Direct • NHL Hockey-Playoffs • TELUS • Mixed Martial Arts • Videotron • Poker • Other (e.g. Netflix, CraveTV, etc.) • Rugby Online Viewing (TV/Video) “$” • Skiing/Ski-Jumping/Snowboarding • Crave TV • Soccer-European • Illico • Soccer-Major League • iTunes/Apple TV • Tennis • Netflix • Wrestling-Professional • TV/Video on Demand Binge Watching • YouTube TV Channels - English • Vimeo • ABC Spark TELEVISION – “Unpaid” • Action Sports Type Watched In Season • Animal Planet • Auto Racing-NASCAR Races • BBC Canada • Auto Racing-Formula 1 Races • BNN Business News Network • Auto -

20-0809-1707+ PD E (Pdf)

CANADIAN BROADCAST STANDARDS COUNCIL ATLANTIC REGIONAL PANEL CJCH-TV, CKCW-TV & ASN re “Save Local TV” campaign (CBSC Decision 08/09-1707+) Decided January 12, 2010 B. Jones (Vice-Chair), R. Cohen (ad hoc), K. Hicks, B. MacEachern, R. McKeen, T.-M. Wiseman and CANADIAN BROADCAST STANDARDS COUNCIL ONTARIO REGIONAL PANEL CJOH-TV, CKCO-TV, CFTO-TV & CKVR-TV re “Save Local TV” campaign (CBSC Decision 08/09-1748+) Decided April 1, 2010 R. Cohen (ad hoc), M. Hamilton, J. David, G. Phelan (ad hoc) THE FACTS This decision deals with separate broadcasts on television outlets owned by CTVglobemedia, which took place in the Atlantic and Ontario Regions. Since the broadcasts fell under the jurisdiction of different CBSC Panels, they were destined to be treated separately. Although the challenged content of the various broadcasts was different, the underlying reasoning was common to both adjudications and, in addition to an individual complainant about an Atlantic CTV station, there was a group complainant 2 filing a single document covering both Atlantic and Ontario CTV station broadcasts. In the circumstances, although the Panel adjudications were held separately, the two Panels agreed that their decisions should be issued in a single document. Throughout 2009, factions of the Canadian broadcasting industry were debating an issue familiarly known as fee-for-carriage (and referred to in that way at material moments in all of the challenged broadcasts dealt with herein). The issue was also subsumed by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) as a part of its determinations listed immediately below under their terminological choice, value-for-signal.