Stanley 1 Here an Analysis of Representation in Media As Applied

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re-Mixing Old Character Tropes on Screen: Kerry Washington, Viola Davis, and the New Femininity by Melina Kristine Dabney A

Re-mixing Old Character Tropes on Screen: Kerry Washington, Viola Davis, and the New Femininity By Melina Kristine Dabney A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Film Studies 2017 This thesis entitled: Re-mixing Old Character Tropes on Screen: Kerry Washington, Viola Davis, and the new Femininity written by Melina Kristine Dabney has been approved for the Department of Film Studies ________________________________________________ (Melinda Barlow, Ph.D., Committee Chair) ________________________________________________ (Suranjan Ganguly, Ph.D., Committee Member) ________________________________________________ (Reiland Rabaka, Ph.D., Committee Member) Date: The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. Dabney, Melina Kristine (BA/MA Film Studies) Re-mixing Old Character Tropes on Screen: Kerry Washington, Viola Davis, and the New Femininity Thesis directed by Professor Melinda Barlow While there is a substantial amount of scholarship on the depiction of African American women in film and television, this thesis exposes the new formations of African American femininity on screen. African American women have consistently resisted, challenged, submitted to, and remixed racial myths and sexual stereotypes existing in American cinema and television programming. Mainstream film and television practices significantly contribute to the reinforcement of old stereotypes in contemporary black women characters. However, based on the efforts of African American producers like Shonda Rhimes, who has attempted to insert more realistic renderings of African American women in her recent television shows, black women’s representation is undergoing yet another shift in contemporary media. -

The Translation of Cultural References and Proper-Name Allusions in the Finnish Subtitles of Gilmore Girls

The Translation of Cultural References and Proper-Name Allusions in the Finnish Subtitles of Gilmore Girls Riikka Vänni Pro Gradu Thesis English Philology Faculty of Humanities University of Oulu Autumn 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………………………………….........................1 2 THE GILMOREVERSE…………………………………………………..............................................................5 2.1 On the Gilmore Girls and genre………………………………………………………………………................5 2.2 On Amy Sherman-Palladino and the target audience……………………………..........................7 3 CULTURE BUMPS AND GILMORE-ISMS………………………………………………………………………………….10 3.1 Defining and categorising cultural references……………………………………………………….………10 3.2 Collecting and analysing the Gilmore-isms………………………………………………………….………..14 4 PREVIOUS RESEARCH AND TRANSLATION STUDIES.…………………………………..............................18 4.1 Previous studies on the Gilmore Girls’ Finnish translations…………………………………….……….18 4.2 The importance of translation: language, culture and the link between………………….………20 4.3 The basics: source versus target……………………………………………………………………………………..22 4.4 Translation method: domestication or foreignisation…………………..…………………………………26 4.5 Reception theory and the target audience……………………………………………………………….…….29 4.6 Audiovisual translation: subtitling and the DVD-industry……………………………………….………31 5 ANALYSING THE GILMORE-ISMS…………………………………………………………………………………..……...34 5.1 References to music……………………………………………………………………………………..………….…..34 5.2 References to films………………………………………………………………………………………..……….…….38 -

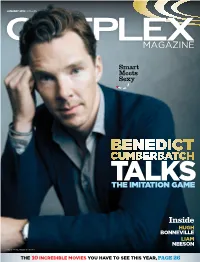

Benedict Cumberbatch Talks the Imitation Game

JANUARY 2015 | VOLUME 16 | NUMBER 1 Smart Meets Sexy BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH TALKS THE IMITATION GAME Inside HUGH BONNEVILLE LIAM NEESON PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 41619533 THE 10 INCREDIBLE MOVIES YOU HAVE TO SEE THIS YEAR, PAGE 26 CONTENTS JANUARY 2015 | VOL 16 | Nº1 COVER STORY 40 GENIUS ROLE Benedict Cumberbatch’s fervent fans won’t be disappointed with his latest role. The Imitation Game casts the 38-year-old Brit as Alan Turing, a gay, mathematical genius who helped hasten the end of WWII. Here he talks about bringing Turing to life and his various other talents BY INGRID RANDOJA REGULARS 4 EDITOR’S NOTE 8 SNAPS 10 IN BRIEF 14 SPOTLIGHT: CANADA 16 ALL DRESSED UP 20 IN THEATRES 44 CASTING CALL 47 RETURN ENGAGEMENT 48 AT HOME 50 FINALLY… FEATURES IMAGE HARGRAVE/AUGUST AUSTIN BY PHOTO COVER 26 2015’S BIG PICS! 32 FABLED CAST 34 MAN OF ACTION 38 PAPA BEAR It’s going to be an epic year We break down which famous Taken 3 star Liam Neeson Paddington’s Hugh Bonneville at the movies. We take you actors play which well-known talks about his longtime says playing father figure to a through the 10 films you must fairy tale characters in love of action movies, and mischievous talking bear gave see, starting with the return of the musical extravaganza recent decision to get clean him the chance to revisit his Star Wars! Into the Woods and healthy own childhood BY INGRID RANDOJA BY INGRID RANDOJA BY BOB STRAUSS BY INGRID RANDOJA JANUARY 2015 | CINEPLEX MAGAZINE | 3 EDITOR’S NOTE PUBLISHER SALAH BACHIR EDITOR MARNI WEISZ DEPUTY EDITOR INGRID RANDOJA ART DIRECTOR TREVOR THOMAS STEWART ASSISTANT ART DIRECTOR STEVIE SHIPMAN VICE PRESIDENT, PRODUCTION SHEILA GREGORY CONTRIBUTORS LEO ALEFOUNDER, BOB STRAUSS ADVERTISING SALES FOR CINEPLEX MAGAZINE AND LE MAGAZINE CINEPLEX IS HANDLED BY CINEPLEX MEDIA. -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

Calabasas City Los Angeles County California, U

CALABASAS CITY LOS ANGELES COUNTY CALIFORNIA, U. S. A. Calabasas, California Calabasas, California Calabasas is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States, Calabasas es una ciudad en el condado de Los Ángeles, California, Estados located in the hills west of the San Fernando Valley and in the northwest Santa Unidos, ubicada en las colinas al oeste del valle de San Fernando y en el noroeste Monica Mountains between Woodland Hills, Agoura Hills, West Hills, Hidden de las montañas de Santa Mónica, entre Woodland Hills, Agoura Hills, West Hills, Hills, and Malibu, California. The Leonis Adobe, an adobe structure in Old Hidden Hills y Malibu, California. El Adobe Leonis, una estructura de adobe en Town Calabasas, dates from 1844 and is one of the oldest surviving buildings Old Town Calabasas, data de 1844 y es uno de los edificios más antiguos que in greater Los Angeles. The city was formally incorporated in 1991. As of the quedan en el Gran Los Ángeles. La ciudad se incorporó formalmente en 1991. A 2010 census, the city's population was 23,058, up from 20,033 at the 2000 partir del censo de 2010, la población de la ciudad era de 23.058, en census. comparación con 20.033 en el censo de 2000. Contents Contenido 1. History 1. Historia 2. Geography 2. Geografía 2.1 Communities 2.1 Comunidades 3. Demographics 3. Demografía 3.1 2010 3.1 2010 3.2 2005 3.2 2005 4. Economy 4. economía 4.1. Top employers 4.1. Mejores empleadores 4.2. Technology center 4.2. -

Universidade Federal Da Bahia Tal Mãe, Tal Filha?

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA FACULDADE DE COMUNICAÇÃO DANIELE MARQUES LIMA TAL MÃE, TAL FILHA? A REPRESENTAÇÃO DAS MULHERES EM GILMORE GIRLS Salvador 2018 DANIELE MARQUES LIMA TAL MÃE, TAL FILHA? A REPRESENTAÇÃO DAS MULHERES EM GILMORE GIRLS Trabalho de conclusão de curso de graduação em Comunicação com Habilitação em Jornalismo, Faculdade de Comunicação, Universidade Federal da Bahia, como requisito parcial para obtenção de grau de Bacharel em Comunicação. Orientadora: Prof. Dr. Marcelo Rodrigues Souza Ribeiro Salvador 2018 DANIELE MARQUES LIMA TAL MAL, TAL FILHA? A REPRESENTAÇÃO DAS MULHERES EM GILMORE GIRLS Monografia apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Bacharel em Comunicação, Faculdade de Comunicação, da Universidade Federal da Bahia. Aprovada em 20 de fevereiro de 2018. Marcelo R. S. Ribeiro – Orientador _______________________________________________ Doutor em Arte e Cultura Visual pela Faculdade de Artes Visuais da Universidade Federal de Goiás (UFG) Mestre em Antropologia Social pela Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC) Universidade Federal da Bahia Marcelo Monteiro Costa _______________________________________________________ Mestre em Comunicação pela Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE) Universidade Federal da Bahia Valéria Maria Sampaio Vilas Bôas Araújo _________________________________________ Mestre em Comunicação e Cultura Contemporânea pela Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA) Universidade Federal da Bahia AGRADECIMENTOS Ao contrário do que pensei, fazer meu segundo Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso não foi fácil. Graduei-me em 2014 em Produção em Comunicação e Cultura, também pela Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA) e, de lá para cá, decidi me aventurar em mais uma graduação. Deu vontade de desistir, medo e até mesmo raiva. Então, diferente do que fiz no meu primeiro TCC, agradeço a mim pelo trabalho desempenhado e pela paciência. -

Ebook Download 1000 Ballet Stickers Ebook, Epub

1000 BALLET STICKERS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sue Meredith,Desideria Guicciardini | 88 pages | 01 Feb 2016 | Usborne Publishing Ltd | 9781409596967 | English | London, United Kingdom 1000 Ballet Stickers PDF Book Fantasy Unicorns Asst. All rights reserved. Please provide a valid price range. Winter Stickers. Tags: coffee, lorelai gilmore, rory gilmore, luke danes, javajunkie, literati, jess mariano, logan huntzberger, iv, drink, need, lauren graham, alexis bledel, tv series, quotes, poddles. Tags: a film by kirk, kirk, film, gilmores, lorelai, girls, rory, quotes, minimal, minimalist, tv show, tv, text, film school, s, funny, humor, tv show quotes, movies, find your thing, films, director, fan, cult movie, show, quote saying, girls, emily, richard, luke, logan, jess, dean, lane. Tangled Stickers. The Loud House Stickers. I Smell Snow! Tags: gilmore girls, rory gilmore, rory gilmore, lorelai gilmore, gilmore girls fan, gilmore girls, logan gilmore girls, jess gilmore girls, rory jess gilmore girls, logan rory gilmore girls, rory logan gilmore girls, lukes gilmore girls, lukes, gilmore girls quotes, stars hollow gilmore girls, stars hollow, stars hollow, gilmore girls, lorelai rory, rory lorelai, luke lorelai, lorelai luke gilmore girls, luke lorelai gilmore girls, in omnia paratus, life and death brigade, gilmoregirls, stars hollow, gilmore girls, gilmore girls designs, gilmore girls, gilmore girls, gilmore girls, gilmore girls. Your local Waterstones may have stock of this item. List View. Bulk Candy. Removable and super stickery. School Stickers. Tags: a film by kirk, tv, series, netflix, gilmore, girls, tv series quotes, tv, tv, quote, lorelai gilmore, rory gilmore, luke danes, lorelai, rory, funny quotes, funny, a film by, film, movies, movie, movie, movie. -

The-Hollywood-Report2c-January-20

Style Wellness Wellness 2017 Glossary CHIRUNNING A running practice that draws L.A.’S BIG-GYM BURNOUT AMID A BOUTIQUE BOOM from tai chi and yoga at 1440 Multiversity, a new Left: Pilates 27-minute Power Plate sessions “learning destination” at Kaska’s ZK Zen — Mark Wahlberg, Madonna in the redwoods of Santa Fitness. and Clint Eastwood partake — Cruz, where Eat Pray Inset: A Love author Elizabeth Power Plate shake users into shape. Kerry machine at Gilbert and Wild’s Cheryl Brentwood’s Washington and Pink do sessions Strayed are faculty PlateFit. at Pilates guru Juliet Kaska’s ZK ($395 tuition, suites from Zen Fitness in Beverly Hills. Says $1,650; 1440.org). How to Get Away With Murder FLEXOLOGIST A profes- actress Liza Weil: “Juliet’s unique sional whose job it is to style transcends the gym. It’s stretch clients’ muscles about how you move in all areas and joints at StretchLab’s of your life.” Now bubbling up Venice, Santa Monica and beloved by Lady Gaga (and or brand-new Hollywood studios ($25 to $69). hen it comes to the shows a 200 percent increase Jude Law’s character on HBO’s W town’s fitness these in studio openings and a mea- The Young Pope), the Gyrotonic ISLAND BATHING A trip to an days, small is huge. sly 7 percent increase in new workout involves movements uninhabited private island While producer Gavin Polone gyms. ModelFIT, the NYC space inside a pulley-based machine for meditation at Antigua’s tells THR that preferring access frequented by Rosie Huntington- that improve posture and stimu- Carlisle Bay, which often hosts studio execs, agents to many apparatuses means Whiteley, recently opened late the nervous system. -

Who Are Your Favorite TV Show Journalists?

For video segments from The Gilmore Girls, Ugly Betty and WKRP in Cincinnati, go to: http://www.poynter.org/latest-news/mediawire/270447/who-are-your-favorite-tv-show-journalists/ Who are your favorite TV show journalists? by Kristen Hare Published Sep. 19, 2014 10:39 am Today is the anniversary of the first episode of the Mary Tyler Moore Show, which debuted in 1970. Poynter’s David Shedden wrote about the show and the recognition it received for today’s media history post. In February, Poynter’s Roy Peter Clark wrote about how journalists are shown in House of Cards. And on Wednesday, Lloyd Grove wrote about a new pack of TV and movie journalists for The Daily Beast. There’s a lot to choose from, so who are your favorite journalists from sitcoms or dramas? I have three. Paris Geller (from The Gilmore Girls. Rory Gilmore is also a favorite, but Paris was a super- journo.) There are a lot of great moments from Paris and Rory’s time at The Yale Daily News, but they started in high school. Betty Suarez (from Ugly Betty.) Betty starts as a secretary at a New York fashion mag, but works her way up and into the magazine’s masthead: And Les Nessman (from WKRP in Cincinnati. Love the bow tie). Who are your picks? (I’ve written about a few before, but I know there are lots more.) Email or tweet me your picks and I’ll pull together a collection. We have made it easy to comment on posts, however we require civility and encourage full names to that end (first initial, last name is OK). -

MEATS Press Notes.Final Clean

MEATS Written & Directed by: Ashley Williams Starring: Ashley Williams Giancarlo Sbarbaro Produced by: Neal Dodson Ashley Williams Film Contact: Neal Dodson, producer 818.481.5473 [email protected] Press Contact: Prodigy Public Relations Erik Bright 310.857.2020 [email protected] For HIGHER-RES still photos & more information please visit: www.ashleywilliams.work MEATS SYNOPSIS Director-writer Ashley Williams also stars in MEATS -- a short film about a pregnant vegan who wrestles with her newfound craving for meat. The film is produced by Williams and her husband, Independent Spirit Award winner and Sundance alum Neal Dodson (Margin Call). MEATS is an exploration of the ethics of meat-eating and the fears inherent with becoming a parent. In the short film, Williams plays Lane, who has hired a whole-animal butcher named Chris (played by real-life master butcher Giancarlo Sbarbaro), to educate her on how to responsibly break down a lamb and use every part. Upon arrival, Lane is simultaneously disgusted and mesmerized by the carcass in front of her. As Lane liberates the meat from the bone, she also frees a whole new side of herself, revealing humor, pain, connection, and a newfound mother-to-be. CounterNarrative Films presents MEATS. The cinematographer is Roman Vasyanov (Triple Frontier, Fury, Sundance alum with The East and Charlie Countryman). The editor is Cecilia Delgado. Color is by Roman Hankewycz (Sundance alum with Sound of Silence and Equity, among others) from Harbor Picture Company. Sound design is by three- time Academy-Award nominee Steve Boeddeker (All Is Lost, Black Panther, Sundance alum with I Origins, among others) at Skywalker Sound. -

F E a T U R E S Summer 2021

FEATURES SUMMER 2021 NEW NEW NEW ACTION/ THRILLER NEW NEW NEW NEW NEW 7 BELOW A FISTFUL OF LEAD ADVERSE A group of strangers find themselves stranded after a tour bus Four of the West’s most infamous outlaws assemble to steal a In order to save his sister, a ride-share driver must infiltrate a accident and must ride out a foreboding storm in a house where huge stash of gold. Pursued by the town’s sheriff and his posse. dangerous crime syndicate. brutal murders occurred 100 years earlier. The wet and tired They hide out in the abandoned gold mine where they happen STARRING: Thomas Nicholas (American Pie), Academy Award™ group become targets of an unstoppable evil presence. across another gang of three, who themselves were planning to Nominee Mickey Rourke (The Wrestler), Golden Globe Nominee STARRING: Val Kilmer (Batman Forever), Ving Rhames (Mission hit the very same bank! As tensions rise, things go from bad to Penelope Ann Miller (The Artist), Academy Award™ Nominee Impossible II), Luke Goss (Hellboy II), Bonnie Somerville (A Star worse as they realize they’ve been double crossed, but by who Sean Astin (The Lord of the Ring Trilogy), Golden Globe Nominee Is Born), Matt Barr (Hatfields & McCoys) and how? Lou Diamond Phillips (Courage Under Fire) DIRECTED BY: Kevin Carraway HD AVAILABLE DIRECTED BY: Brian Metcalf PRODUCED BY: Eric Fischer, Warren Ostergard and Terry Rindal USA DVD/VOD RELEASE 4DIGITAL MEDIA PRODUCED BY: Brian Metcalf, Thomas Ian Nicholas HD & 5.1 AVAILABLE WESTERN/ ACTION, 86 Min, 2018 4K, HD & 5.1 AVAILABLE USA DVD RELEASE -

Gilmore Girls”

For Immediate Release THE UP FAMILY EXPANDS UP Acquires Full Seven-Season Run of Award-Winning, Fan-Favorite Series “Gilmore Girls” Family Network to Begin Airing Episodes in the Fall LOS ANGELES / Television Critics Association – July 30, 2015 – UP announced today it has acquired the full seven-season run of "Gilmore Girls," the award-winning, fan-favorite family drama starring Lauren Graham ("Parenthood"), Alexis Bledel (The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants), Melissa McCarthy ("Mike & Molly,” Spy), Keiko Agena “(“Shameless,” Transformers of the Dark Moon), Yanic Truesdale (“Reumeurs"), Scott Patterson ("CSI Miami"), Liza Weil ("Stir of Echoes"), Jared Padalecki ("Supernatural"), Milo Ventimiglia ("Heroes"), Sean Gunn (Guardians of the Gun, Pearl Harbor) and Kelly Bishop ("Bunhead," “The Good Wife”), with special appearances by the late Edward Herrmann (The Wolf of Wall Street, The Lost Boys) and recurring guest star Liz Torres ("Devious Maids,” ”Scandal"). UP acquired "Gilmore Girls" from Warner Bros. Domestic Television Distribution and will begin airing the 153 one-hour episodes of the series in the fall. The announcement was made by Amy Winter, evp and general manager, UP. She said, "We’ve acquired one of the most beloved shows in family TV history and we are thrilled to add such a critically acclaimed family series to our line up.” The acquisition of "Gilmore Girls" was negotiated by Sophia Kelley, svp programming, UP, who said, "'Gilmore Girls' is a fan-favorite series that retains a very large and passionate following. The strong and loving mother- daughter relationship portrayed in ‘Gilmore Girls’ is a beautiful testament to the wonderful power of family drama.