The Case of the Ultimate Fighting Championship A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunday Morning Grid 4/1/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

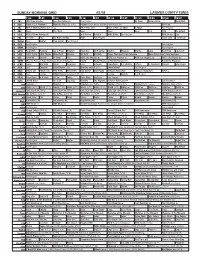

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/1/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program JB Show History Astro. Basketball 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Boston Bruins at Philadelphia Flyers. (N) PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Jazzy Real Food Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Misa de Pascua: Papa Francisco desde el Vaticano Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

BISPING: Barnett Needs to Push the Pace Vs. Nelson

FS1 UFC TONIGHT Show Quotes – 9/23/15 BISPING: Barnett Needs To Push The Pace Vs. Nelson Florian: “Uriah Hall Is Too Dangerous To Just Stand and Trade With” LOS ANGELES – UFC TONIGHT host Kenny Florian and guest host Michael Bisping break down the upcoming FS1 UFC FIGHT NIGHT: BARNETT VS. NELSON. Karyn Bryant and Ariel Helwani add reports. UFC TONIGHT guest host Michael Bisping on how Josh Barnett can beat Roy Nelson: “Josh needs to not get hit by the right hand of Roy. He needs to push the pace of the fight, move forward, and push Roy up against fence and brutalize him with knees and elbows like he did with Frank Mir. Most of his finishes came from the clinch position. He finishes fights against the fence. He did that against Frank Mir.” UFC TONIGHT host Kenny Florian on Barnett avoiding Nelson’s knock out power: “Josh doesn’t want to be on the outside where Roy’s right hand can get him. He wants to be on the inside. He’s been busy on the submission circuit. He’s dangerous on the mat and that’s where he wants to get Roy.” Bisping on how Nelson should fight Barnett: “What Roy can’t get is predictable. If he just tries to throw the big right hand, Barnett is going to see it coming. Roy has to mix up his striking. I’m not sure he’s going to go for takedowns. But he has to mix his striking. His right hand and left hooks, to keep Josh at bay.” Florian on Nelson mixing up his strikes: “The knock on Nelson is his lack of evolution. -

2020 WWE Finest

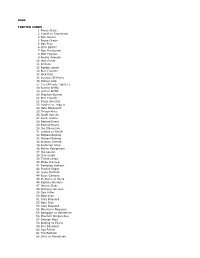

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Angel Garza Raw® 2 Akam Raw® 3 Aleister Black Raw® 4 Andrade Raw® 5 Angelo Dawkins Raw® 6 Asuka Raw® 7 Austin Theory Raw® 8 Becky Lynch Raw® 9 Bianca Belair Raw® 10 Bobby Lashley Raw® 11 Murphy Raw® 12 Charlotte Flair Raw® 13 Drew McIntyre Raw® 14 Edge Raw® 15 Erik Raw® 16 Humberto Carrillo Raw® 17 Ivar Raw® 18 Kairi Sane Raw® 19 Kevin Owens Raw® 20 Lana Raw® 21 Liv Morgan Raw® 22 Montez Ford Raw® 23 Nia Jax Raw® 24 R-Truth Raw® 25 Randy Orton Raw® 26 Rezar Raw® 27 Ricochet Raw® 28 Riddick Moss Raw® 29 Ruby Riott Raw® 30 Samoa Joe Raw® 31 Seth Rollins Raw® 32 Shayna Baszler Raw® 33 Zelina Vega Raw® 34 AJ Styles SmackDown® 35 Alexa Bliss SmackDown® 36 Bayley SmackDown® 37 Big E SmackDown® 38 Braun Strowman SmackDown® 39 "The Fiend" Bray Wyatt SmackDown® 40 Carmella SmackDown® 41 Cesaro SmackDown® 42 Daniel Bryan SmackDown® 43 Dolph Ziggler SmackDown® 44 Elias SmackDown® 45 Jeff Hardy SmackDown® 46 Jey Uso SmackDown® 47 Jimmy Uso SmackDown® 48 John Morrison SmackDown® 49 King Corbin SmackDown® 50 Kofi Kingston SmackDown® 51 Lacey Evans SmackDown® 52 Mandy Rose SmackDown® 53 Matt Riddle SmackDown® 54 Mojo Rawley SmackDown® 55 Mustafa Ali Raw® 56 Naomi SmackDown® 57 Nikki Cross SmackDown® 58 Otis SmackDown® 59 Robert Roode Raw® 60 Roman Reigns SmackDown® 61 Sami Zayn SmackDown® 62 Sasha Banks SmackDown® 63 Sheamus SmackDown® 64 Shinsuke Nakamura SmackDown® 65 Shorty G SmackDown® 66 Sonya Deville SmackDown® 67 Tamina SmackDown® 68 The Miz SmackDown® 69 Tucker SmackDown® 70 Xavier Woods SmackDown® 71 Adam Cole NXT® 72 Bobby -

Cultivating Identity and the Music of Ultimate Fighting

CULIVATING IDENTITY AND THE MUSIC OF ULTIMATE FIGHTING Luke R Davis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Megan Rancier, Advisor Kara Attrep © 2012 Luke R Davis All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Megan Rancier, Advisor In this project, I studied the music used in Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) events and connect it to greater themes and aspects of social study. By examining the events of the UFC and how music is used, I focussed primarily on three issues that create a multi-layered understanding of Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) fighters and the cultivation of identity. First, I examined ideas of identity formation and cultivation. Since each fighter in UFC events enters his fight to a specific, and self-chosen, musical piece, different aspects of identity including race, political views, gender ideologies, and class are outwardly projected to fans and other fighters with the choice of entrance music. This type of musical representation of identity has been discussed (although not always in relation to sports) in works by past scholars (Kun, 2005; Hamera, 2005; Garrett, 2008; Burton, 2010; Mcleod, 2011). Second, after establishing a deeper sense of socio-cultural fighter identity through entrance music, this project examined ideas of nationalism within the UFC. Although traces of nationalism fall within the purview of entrance music and identity, the UFC aids in the nationalistic representations of their fighters by utilizing different tactics of marketing and fighter branding. Lastly, this project built upon the above- mentioned issues of identity and nationality to appropriately discuss aspects of how the UFC attempts to depict fighter character to create a “good vs. -

UFC Fight Night: Dos Anjos Vs

UFC Fight Night: Dos Anjos vs. Alvarez Live Main Card Highlights UFC 200 Fight Week Coverage on Fight Network Toronto – Fight Network, the world’s premier 24/7 multi- platform channel dedicated to complete coverage of combat sports, today announced extensive live coverage for UFC International Fight Week™ in Las Vegas, the biggest week in UFC history, highlighted by a live broadcast of the main card for UFC FIGHT NIGHT®: DOS ANJOS vs. ALVAREZ from the MGM Grand Garden Arena on Thursday, July 7 at 10 p.m. ET, plus the live prelims for THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER FINALE®: Team Joanna vs. Team Claudia on Friday, July 8 at 8 p.m. ET. Fight Network will air the live UFC FIGHT NIGHT®: DOS ANJOS vs. ALVAREZ main card across Canada on July 7 at 10 p.m. ET, preceded by a live Pre-Show at 9 p.m. ET. In the main event, dominant UFC lightweight champion Rafael dos Anjos (24-7) puts his championship on the line in a five- round barnburner against top contender Eddie Alvarez (27-4). In other featured bouts, Roy “Big Country” Nelson (22-12) throws down with Derrick “The Black Beast” Lewis (15-4, 1NC) in an explosive heavyweight collision, Alan Jouban (13-4) takes on undefeated Belal Muhammad (9-0) in a welterweight affair, plus “Irish” Joe Duffy (14-2) welcomes Canada’s Mitch “Danger Zone” Clarke (11-3) back to action in a lightweight matchup. Live fight week coverage begins on Wednesday, July 6 at 2 p.m. ET with a live presentation of the final UFC 200 pre-fight press conference, featuring UFC president Dana White and main card superstars Jon Jones, Daniel Cormier, Brock Lesnar, Mark Hunt, Miesha Tate, Amanda Nunes, Jose Aldo and Frankie Edgar. -

Hit Show Dana White's Contender Series

HIT SHOW DANA WHITE’S CONTENDER SERIES CONTINUES ITS FOURTH SEASON WITH EPISODE 7 AIRING LIVE TUESDAY FROM UFC APEX IN LAS VEGAS Las Vegas – The fourth season of the hit show Dana White’s Contender Series continues with Episode 7, featuring a lineup of rising athletes looking to make their dreams come true by impressing UFC President Dana White and earning a spot on the UFC roster. The seventh episode of season four takes place on Tuesday, September 15 at 8 p.m. ET / 5 p.m. PT, with all five bouts streaming exclusively on ESPN+ in the US. ESPN+ is available through the ESPN.com, ESPNPlus.com or the ESPN App on all major mobile and connected TV devices and platforms, including Amazon Fire, Apple, Android, Chromecast, PS4, Roku, Samsung Smart TVs, X Box One and more. Fans can sign up for $4.99 per month or $49.99 per year, with no contract required. To support your coverage, please find the download link to the season four sizzle reels here and here. In addition, please find the download link for the season four athlete feature here, which highlights some of the participating athletes, their backgrounds and what competing on Dana White’s Contender Series means to them. Season 4, Episode 7 – Confirmed Bouts: Middleweight Gregory Rodrigues vs. Jordan Williams Featherweight Muhammad Naimov vs. Collin Anglin Welterweight Korey Kuppe vs. Michael Lombardo Women’s featherweight Danyelle Wolf vs. Taneisha Tennant Featherweight Dinis Paiva vs. Kyle Driscoll Visit the UFC.com for information and additional content to support your UFC coverage. -

Brooks, UFC, Mars Giving Las Vegas Big Back-To- Back Weekends by Richard N

Brooks, UFC, Mars giving Las Vegas big back-to- back weekends By Richard N. Velotta Las Vegas Review-Journal July 8, 2021 - 11:14 pm Normally, there’s a tourism lull the week after a three-day weekend. But as everyone knows, 2021 is far from normal, and the weekend after the three-day Fourth of July holiday has the makings of a blockbuster for Las Vegas. Credit a supercluster of blockbuster entertainment coming up in the city this weekend. The UFC 264 event at T-Mobile Arena, featuring Conor McGregor-Dustin Poirier. Garth Brooks at Allegiant Stadium. Bruno Mars at Park MGM. On top of that, former President Donald Trump is planning to attend the big fight, UFC President Dana White confirmed Thursday. The Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority doesn’t have any historical data to calculate an estimate of how many people will venture to Las Vegas this weekend, but most observers think more than 300,000 people were in the city over the Fourth of July three-day holiday. Will 300,000 more be here this weekend? Testing transportation If nothing else, the existing transportation grid will be put to the test with three major events — the Garth Brooks concert, the UFC fights and Bruno Mars — occurring at venues within a half-mile of each other at right around the same time that night. But health officials have expressed concern that big crowds have the potential to create superspreader events. Nevada on Thursday reported 697 new coronavirus cases and two deaths as the state’s test positivity rate continued to climb. -

Are Ufc Fighters Employees Or Independent Contractors?

Conklin Book Proof (Do Not Delete) 4/27/20 8:42 PM TWO CLASSIFICATIONS ENTER, ONE CLASSIFICATION LEAVES: ARE UFC FIGHTERS EMPLOYEES OR INDEPENDENT CONTRACTORS? MICHAEL CONKLIN* I. INTRODUCTION The fighters who compete in the Ultimate Fighting Championship (“UFC”) are currently classified as independent contractors. However, this classification appears to contradict the level of control that the UFC exerts over its fighters. This independent contractor classification severely limits the fighters’ benefits, workplace protections, and ability to unionize. Furthermore, the friendship between UFC’s brash president Dana White and President Donald Trump—who is responsible for making appointments to the National Labor Relations Board (“NLRB”)—has added a new twist to this issue.1 An attorney representing a former UFC fighter claimed this friendship resulted in a biased NLRB determination in their case.2 This article provides a detailed examination of the relationship between the UFC and its fighters, the relevance of worker classifications, and the case law involving workers in related fields. Finally, it performs an analysis of the proper classification of UFC fighters using the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) Twenty-Factor Test. II. UFC BACKGROUND The UFC is the world’s leading mixed martial arts (“MMA”) promotion. MMA is a one-on-one combat sport that combines elements of different martial arts such as boxing, judo, wrestling, jiu-jitsu, and karate. UFC bouts always take place in the trademarked Octagon, which is an eight-sided cage.3 The first UFC event was held in 1993 and had limited rules and limited fighter protections as compared to the modern-day events.4 UFC 15 was promoted as “deadly” and an event “where anything can happen and probably will.”6 The brutality of the early UFC events led to Senator John * Powell Endowed Professor of Business Law, Angelo State University. -

2015 Topps UFC Chronicles Checklist

BASE FIGHTER CARDS 1 Royce Gracie 2 Gracie vs Jimmerson 3 Dan Severn 4 Royce Gracie 5 Don Frye 6 Vitor Belfort 7 Dan Henderson 8 Matt Hughes 9 Andrei Arlovski 10 Jens Pulver 11 BJ Penn 12 Robbie Lawler 13 Rich Franklin 14 Nick Diaz 15 Georges St-Pierre 16 Patrick Côté 17 The Ultimate Fighter 1 18 Forrest Griffin 19 Forrest Griffin 20 Stephan Bonnar 21 Rich Franklin 22 Diego Sanchez 23 Hughes vs Trigg II 24 Nate Marquardt 25 Thiago Alves 26 Chael Sonnen 27 Keith Jardine 28 Rashad Evans 29 Rashad Evans 30 Joe Stevenson 31 Ludwig vs Goulet 32 Michael Bisping 33 Michael Bisping 34 Arianny Celeste 35 Anderson Silva 36 Martin Kampmann 37 Joe Lauzon 38 Clay Guida 39 Thales Leites 40 Mirko Cro Cop 41 Rampage Jackson 42 Frankie Edgar 43 Lyoto Machida 44 Roan Carneiro 45 St-Pierre vs Serra 46 Fabricio Werdum 47 Dennis Siver 48 Anthony Johnson 49 Cole Miller 50 Nate Diaz 51 Gray Maynard 52 Nate Diaz 53 Gray Maynard 54 Minotauro Nogueira 55 Rampage vs Henderson 56 Maurício Shogun Rua 57 Demian Maia 58 Bisping vs Evans 59 Ben Saunders 60 Soa Palelei 61 Tim Boetsch 62 Silva vs Henderson 63 Cain Velasquez 64 Shane Carwin 65 Matt Brown 66 CB Dollaway 67 Amir Sadollah 68 CB Dollaway 69 Dan Miller 70 Fitch vs Larson 71 Jim Miller 72 Baron vs Miller 73 Junior Dos Santos 74 Rafael dos Anjos 75 Ryan Bader 76 Tom Lawlor 77 Efrain Escudero 78 Ryan Bader 79 Mark Muñoz 80 Carlos Condit 81 Brian Stann 82 TJ Grant 83 Ross Pearson 84 Ross Pearson 85 Johny Hendricks 86 Todd Duffee 87 Jake Ellenberger 88 John Howard 89 Nik Lentz 90 Ben Rothwell 91 Alexander Gustafsson -

Ufc® 165 Fight Between Jon Jones and Alexander Gustafsson to Be Inducted Into Ufc® Hall of Fame

UFC® 165 FIGHT BETWEEN JON JONES AND ALEXANDER GUSTAFSSON TO BE INDUCTED INTO UFC® HALL OF FAME Las Vegas – UFC® today announced that the classic 2013 fight between UFC light heavyweight champion Jon Jones and Alexander Gustafsson will be inducted into the UFC Hall of Fame’s ‘Fight Wing’ as part of the Class of 2020. The 2020 UFC Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony, presented by Toyo Tires®, will take place on Thursday, July 9, at The Pearl at Palms Casino Resort in Las Vegas. The event will be streamed live on UFC FIGHT PASS®. “Going into the first Jones vs. Gustafsson fight, fans and media didn’t care about the fight, because they didn’t believe Gustafsson deserved a title shot, and this thing ended up being the greatest light heavyweight title fight in UFC history,” UFC President Dana White said. “To be there and watch it live was amazing. It was an incredible fight and both athletes gave everything they had for all five rounds. This fight was such a classic it was named the 2013 Fight of the Year and will always be considered one of the greatest fights in combat sports history. This fight showed what a true champion Jon Jones was, as this was the first time he was taken into deep waters and truly tested. This fight also put Gustafsson on the map and showed his true potential. Congratulations to Jon Jones and Alexander Gustafsson on being inducted into the UFC Hall of Fame ‘Fight Wing’ for such an epic fight.” As the main event of UFC® 165: JONES vs. -

Outside the Cage: the Political Campaign to Destroy Mixed Martial Arts

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2013 Outside The Cage: The Political Campaign To Destroy Mixed Martial Arts Andrew Doeg University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Doeg, Andrew, "Outside The Cage: The Political Campaign To Destroy Mixed Martial Arts" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2530. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2530 OUTSIDE THE CAGE: THE CAMPAIGN TO DESTROY MIXED MARTIAL ARTS By ANDREW DOEG B.A. University of Central Florida, 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2013 © 2013 Andrew Doeg ii ABSTRACT This is an early history of Mixed Martial Arts in America. It focuses primarily on the political campaign to ban the sport in the 1990s and the repercussions that campaign had on MMA itself. Furthermore, it examines the censorship of music and video games in the 1990s. The central argument of this work is that the political campaign to ban Mixed Martial Arts was part of a larger political movement to censor violent entertainment. -

The Oral Poetics of Professional Wrestling, Or Laying the Smackdown on Homer

Oral Tradition, 29/1 (201X): 127-148 The Oral Poetics of Professional Wrestling, or Laying the Smackdown on Homer William Duffy Since its development in the first half of the twentieth century, Milman Parry and Albert Lord’s theory of “composition in performance” has been central to the study of oral poetry (J. M. Foley 1998:ix-x). This theory and others based on it have been used in the analysis of poetic traditions like those of the West African griots, the Viking skalds, and, most famously, the ancient Greek epics.1 However, scholars have rarely applied Parry-Lord theory to material other than oral poetry, with the notable exceptions of musical forms like jazz, African drumming, and freestyle rap.2 Parry and Lord themselves, on the other hand, referred to the works they catalogued as performances, making it possible to use their ideas beyond poetry and music. The usefulness of Parry-Lord theory in studies of different poetic traditions tempted me to view other genres of performance from this perspective. In this paper I offer up one such genre for analysis —professional wrestling—and show that interpreting the tropes of wrestling through the lens of composition in performance provides information that, in return, can help with analysis of materials more commonly addressed by this theory. Before beginning this effort, it will be useful to identify the qualities that a work must possess to be considered a “composition in performance,” in order to see if professional wrestling qualifies. The first, and probably most important and straightforward, criterion is that, as Lord (1960:13) says, “the moment of composition is the performance.” This disqualifies art forms like theater and ballet, works typically planned in advance and containing words and/or actions that must be performed at precise times and following a precise order.