A Framework of an Effective Online Help System to Support Nurses Using a Nursing Information System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Storageworks RAID Array 200 Online Mgt Utility for Openvms AXP User's

StorageWorks RAID Array 200 Online Management Utility for OpenVMS AXP User's Guide AA–Q6WVB–TE Digital Equipment Corporation Maynard, Massachusetts Second Printing, April 1995 The information in this document is subject to change without notice and should not be construed as a commitment by Digital Equipment Corporation. Digital Equipment Corporation assumes no responsibility for any errors that might appear in this document. The software, if any, described in this document is furnished under a license and may be used or copied only in accordance with the terms of such license. No responsibility is assumed for the use or reliability of software or equipment that is not supplied by Digital Equipment Corporation or its affiliated companies. Copyright 1995 by Digital Equipment Corporation. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. The following are trademarks of Digital Equipment Corporation: AXP, OpenVMS, StorageWorks, SWXCR, and the Digital logo. The following are third-party trademarks: Microsoft and MS-DOS are registered trademarks and Windows is a trademark of Microsoft Corporation. Intel, Intel486, and i486 are trademarks of Intel Corporation. All other trademarks and registered trademarks are the property of their respective holders. Contents Revision Record...................................................................................................................ix About This Guide ...............................................................................................................xi 1 Installing the RAID Array -

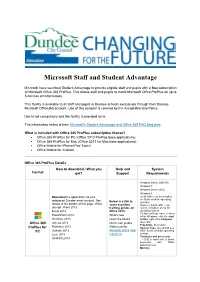

Microsoft Staff and Student Advantage

Microsoft Staff and Student Advantage Microsoft have launched Student Advantage to provide eligible staff and pupils with a free subscription of Microsoft Office 365 ProPlus. This allows staff and pupils to install Microsoft Office ProPlus on up to 5 devices simultaneously. This facility is available to all staff and pupils in Dundee schools exclusively through their Dundee Microsoft Office365 account. Use of this account is covered by the Acceptable Use Policy. Use is not compulsory and the facility is provided as-is. The information below is from Microsoft's Student Advantage and Office 365 FAQ blog post. What is included with Office 365 ProPlus subscription license? Office 365 ProPlus for PC (Office 2013 ProPlus base applications) Office 365 ProPlus for Mac (Office 2011 for Mac base applications) Office Mobile for iPhone/iPod Touch Office Mobile for Android Office 365 ProPlus Details How to download / What you Help and System Format get? Support Requirements Windows Server 2008 R2 Windows 7 Windows Server 2012 Windows 8 Download the application via your 32-bit Office can be installed webbased Dundee email account, See on 32-bit or 64-bit operating Below is a link to systems. details at the bottom of this page. What some excellent However 64-bit Office can you get: Word 2013 training guides on only be installed on 64-bit Excel 2013 Office 2013: operating system. To find out if you have 32-bit or PowerPoint 2013 What's new 64-bit Windows, click the start OneNote 2013 Learn the basics button, right-click Computer Office 365 Access 2013 Quick start guides then click Properties, then under ProPlus for Publisher 2013 Video tutorials System Type you should see PC Outlook 2013 Microsoft online help either 32-bit or 64-bit operating Lync 2013 resources system. -

The Top 10 Mistakes to Avoid When Starting an Online Help Project

Th e top 10 mistakes to avoid when starting an online help project Whitepaper Th e top 10 mistakes to avoid when starting an online help project Modern help authoring tools like RoboHelp® are very powerful and offer great flexibility to authors. However, the same power and flexibility can get new projects off to a bad start. Some mistakes are plain silly, while others can lead to hiring the wrong author, picking the wrong output format, or letting a project spin out of control in ways that call for expensive rework later. The risk involved in employing modern help authoring tools has existed ever since they appeared in 1991. Thereafter, these tools became even more powerful and feature-rich expanding the scope for errors. Two changes in the recent years can magnify the effect of such mistakes: • The ‘internalization’ of help into an accelerating documentation process In the past, help authors could make mistakes and had time to find, fix, and learn from them. But Test drive Adobe® RoboHelp 9 today, tighter time-to-market and ROI (return on investment) demands are eliminating the authors’ Try the full functionality of ability to make and learn from mistakes. It’s more important than ever to ‘get it right the first time’. RoboHelp 9 (as a part of Adobe Technical Communication Suite 3.5) • The shift from viewing online help as ‘documentation’ to ‘content’ for reuse beyond the in minutes—without downloading boundaries of the doc group the soft ware. Tutorials are also included. To test drive RoboHelp 9 Help authors now have to consider how their content may be used on a company web site, now, visit www.runaware.com/ on mobile devices, or can be found via Google searches, and more. -

![ICUT MS Agreement 2[1].0 Order Form 8-15-2001](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2289/icut-ms-agreement-2-1-0-order-form-8-15-2001-1062289.webp)

ICUT MS Agreement 2[1].0 Order Form 8-15-2001

Independent Colleges and Universities of Texas (ICUT)- Microsoft® Campus Agreement 2.0 Faculty/Staff Work-at-Home Media Order Form (revised 8-15-01; expires 8-31-2002) ICUT sponsors a Microsoft® Campus Agreement 2.0. Eligible schools: Abilene Christian U., Austin College, Baylor U., Concordia U. at Austin, East Texas Baptist U., Houston Baptist U., Howard Payne U., Jacksonville College, Jarvis Christian College, Le Tourneau U., Lon Morris College, Lubbock Christian U., Mc Murry U., Our Lady of the Lake U., St. Edward’s U., Southwestern Adventist U., Southwestern Christian College, Texas Christian U., Texas College, Trinity U., U. of Mary Hardin-Baylor, U. of St. Thomas. Participating colleges have paid the license fee for the media (CD-ROMs) available below that faculty/staff can order for work-at-home use. Because you are only paying for the media, the prices are very low. FCCC is providing the media and accepts both credit cards and personal checks; orders can be mailed or faxed. The license agreement with Microsoft® does not include free access to phone help from Microsoft®. Hardcopy manuals are not included but are available online from Microsoft®. There is also online help at www.microsoft.com and FCCC provides limited technical assistance by email. See the FCCC website (www.facultybuys.org) for additional information, including other discounted products and services. All disks are fully guaranteed; defective disks are replaced at no charge. All sets are fully licensed copies as long as your college Microsoft® Campus Agreement 2.0 is in place. Windows®98 SE Upgrade, Windows® Me Upgrade, and Windows® 2000 Upgrade require a previous version of Windows® on your computer. -

Help for HTML Help

Microsoft HTML Help Overview Microsoft® HTML Help consists of an online Help Viewer, related help components, and help authoring tools from Microsoft Corporation. The Help Viewer uses the underlying components of Microsoft Internet Explorer to display help content. It supports HTML, ActiveX®, Java™, scripting languages (JScript®, and Microsoft Visual Basic® Scripting Edition), and HTML image formats (.jpeg, .gif, and .png files). The help authoring tool, HTML Help Workshop, provides an easy-to-use system for creating and managing help projects and their related files. Features About creating help Satellite .dll files enable help in all supported languages. Now help will Newa flewatuaryess i nm thias trcelhea stehe language of the installed operating system. Microsoft® HTML Help version 1.3 contains these new features: There is now a single version of Hhupd.exe that works in all supported languages. NOTE: These enhancements are designed to make HTML Help fully compliant with the language features of Microsoft Windows® 2000. For more information on multiple language support in Windows 2000, see the Multilanguage Support white paper on the Microsoft Windows 2000 Web site. Introducing HTML Help help system or Web site. The HTML Help components HTML Help contains the following components: HTML Help ActiveX control: a small, modular program used to insert help navigation and secondary window functionality into an HTML file. The HTML Help Viewer: a fully-functional and customizable three- paned window in which online help topics can appear. Microsoft HTML Help Image Editor: an online graphics tool for creating screen shots; and for converting, editing, and viewing image files. The HTML Help Java Applet: a small, Java-based program that can be used instead of an ActiveX control to insert help navigation into an HTML file. -

Online Help – MOVI-PLC® Power Apps 3 ® 1 Welcome to "MOVI-PLC Power Apps"

Drive Technology \ Drive Automation \ System Integration \ Services Manual MOVI-PLC® power apps Edition 03/2013 20102143 / EN SEW-EURODRIVE—Driving the world Contents Contents 1 Welcome to "MOVI-PLC® power apps"............................................................. 4 2 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Which functions does the software offer? ................................................... 5 2.2 Which groups are the functions assigned to? ............................................. 5 3 Operation ............................................................................................................. 6 3.1 First steps ................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1 Start screen ................................................................................. 6 3.1.2 Program layout ............................................................................ 7 3.1.3 Starting and quitting the program manually................................. 8 3.1.4 Unit detection indicator ................................................................ 8 3.2 "Program" group ......................................................................................... 9 3.3 "Data management" group........................................................................ 10 3.3.1 Write protection and reserved RAM........................................... 10 3.3.2 Setting up write protection and reserved -

IBM Tivoli Netview for Z/OS: Command Reference Volume 2 (O-Z) for Netview for Z/OS Terms and Definitions, See the IBM Terminology Web Site

IBM Tivoli NetView for z/OS Version 6 Release 2 Modification 1 Command Reference Volume 2 (O – Z) IBM SC27-2848-06 Note Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page 611. This edition applies to version 6, release 2, modification 1 of IBM Tivoli NetView for z/OS (product number 5697-NV6 ) and to all subsequent versions, releases, and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. This edition replaces SC27-2848-05. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 1997, 2015. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents Figures................................................................................................................. ix About this publication...........................................................................................xi Intended audience...................................................................................................................................... xi Publications................................................................................................................................................. xi IBM Tivoli NetView for z/OS library....................................................................................................... xi Related publications ............................................................................................................................ xii Accessing terminology online...............................................................................................................xii -

Microsoft Visual Studio .NET: an Integrated Windows Program

Microsoft Visual Using Microsoft Visual Studio .NET Studio .NET: ? Self-contained environment for Windows program development: An Integrated – creating – compiling Windows Program – linking – testing/debugging Development ? IDE that accompanies Visual C++, Visual Basic, Visual C#, and other Microsoft Environment Windows programming languages ? See Chapter 2 and Appendix D of Deitel text ? Also Appendix C of Gregory text Some Visual Studio Visual Studio Capabilities Components ? Generate starter applications without writing ? The Editors code C, C++, C#, VB source program text editors ? View a programming project in many different • cut/paste, color cues, indentation, ways • generates text files ? Edit source and include files Resource Editors ? Build the application’s user interface visually • icons, bitmaps, cursors, menus, dialog boxes, etc. • graphical, WYSIWYG, Integrated ? Compile and link • generates resource script (.rc) files ? Debug an application while it runs • integrated with text editor ? Obtain online help • Done visually ? Lots of others VC++ Unmanaged Code The Linker Compiler ? C/C++ Compiler ? Reads compiler .obj/.res files – translates source programs to machine language ? – detects and reports errors Accesses C/C++/Windows libraries – generates object (.obj) files for linker ? Generates executable (.exe or .dll) ? Resource Compiler – Reads .rc file – Generates binary resource (.res) file for linker 1 The Debugger ? powerful source code debugger ? integrated with all parts of Visual Studio ? Features – breakpoints – -

Z/OS Information Roadmap

z/OS Version 2 Release 3 z/OS Information Roadmap IBM SA23-2299-30 Note Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page 51. This edition applies to Version 2 Release 3 of z/OS (5650-ZOS) and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. Last updated: 2019-06-24 © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 1988, 2019. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents Tables................................................................................................................... v How to send your comments to IBM......................................................................vii If you have a technical problem.................................................................................................................vii Summary of changes.............................................................................................ix Summary of changes for z/OS Version 2 Release 3 (V2R3)....................................................................... ix Summary of changes for z/OS Version 2 Release 2 (V2R2)....................................................................... ix z/OS Version 2 Release 1 summary of changes.......................................................................................... x Chapter 1. Accessing z/OS documentation............................................................. 1 Cross-document -

Applying Document Design to Online Help Systems to Increase Usability

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Spring 2017 Merging Mediums: Applying Document Design to Online Help Systems to Increase Usability Meghan M. Smith Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Technical and Professional Writing Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Meghan M., "Merging Mediums: Applying Document Design to Online Help Systems to Increase Usability" (2017). MSU Graduate Theses. 3064. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3064 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MERGING MEDIUMS: APPLYING DOCUMENT DESIGN TO ONLINE HELP SYSTEMS TO INCREASE USABILITY A Master’s Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, Writing By Meghan M. Smith May 2017 Copyright 2017 by Meghan Marie Smith ii MERGING MEDIUMS: APPLYING DOCUMENT DESIGN TO ONLINE HELP SYSTEMS TO INCREASE USABILITY English Missouri State University, May 2017 Master of Arts Meghan M. -

Visual Basic 2010 MSDN

Copyright 2010-2014 by Homeschool Programming, Inc. Download and Installation Instructions for Visual Basic 2010 Help Library Updated April, 2014 The Visual Basic 2010 Help Library contains reference documentation and information that will provide you with extra assistance on any programming topic with just a click of a button. These help files are not necessary for the completion of your course; however they are a helpful resource. Until the Microsoft Visual Studio 2010 release, the “Help Library” was named the “MSDN (Microsoft Developer Network) Library”, and therefore you will see these terms used interchangeably in the programming industry and also within our curriculum. You may choose to configure and use the Help Library in one of two ways: • Online Help – With this option you simply configure your Visual Basic 2010 Express software to automatically go online to Microsoft’s website whenever you need to pull up any help topic. No local download or install is required, although you will need a persistent Internet connection for this option to work. • Local Help – With this option you choose components of the Help Library and download and install them on your computer. The Help Library consists of a number of optional components that are very large and may take a long time to download and install on your computer, even with a high speed Internet connection. However, once the installation is complete, you no longer need an Internet connection to pull up help topics. We recommend using the Online Help option if possible for your student’s computer due to the speed and simplicity of this option. -

Choosing Between Help Authoring Tools and Ccmss Introduction

WHITE PAPER Comparison Guide: Choosing Between Help Authoring Tools and CCMSs Introduction Introduction Every few years, the debate flares up over whether to use a HAT (help authoring tool) or a CMS (content management system) to create online Help and documentation. The gist of the debate is that HATs, which appeared in 1991, are outdated and should be replaced by a CMS or, today, by a CCMS (component content management system). This white paper, which revisits that debate, touches upon topics that may help your company avoid repeating the mistakes of the 1990s when companies bought HATs without first distinguishing between different HATs’ feature sets and workflows. Note: for the purposes of this white paper, Flare is categorized as a HAT. However, Flare, like all modern HATs, went far beyond simple help authoring long ago to become the single-sourcing, multiple output powerhouses of today. The comments on the HAT side apply to most HATs but focus on Flare. The comments about the CCMS side are generic. Let’s start with a few definitions. l HATs let us create online Help and documentation in multiple online and print formats. A HAT stores the files that form a project – topics, content “fragments” like variables and snippets, plus control files like skins and stylesheets – as separate chunks using the standard Windows file structure. l CMSs (content management systems) can also create online Help and documentation in online and print formats, although they have other uses as well. Like HATs, CMSs work with chunks. The definition of “chunk” depends on the CMS, but it’s often a page or a document, such as a set of Word documents stored as individual chunks in a CMS.