Geographies of New Orleans by Richard Campanella Please Order on Amazon.Com Geographies of New Orleans by Richard Campanella

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lessons from the People Surrounding the Lafitte Greenway in New Orleans, Louisiana Philip Koske

Proceedings of the Fábos Conference on Landscape and Greenway Planning Volume 4 Article 34 Issue 1 Pathways to Sustainability 2013 Connecting the “Big Easy”: Lessons from the people surrounding the Lafitte Greenway in New Orleans, Louisiana Philip Koske Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/fabos Part of the Botany Commons, Environmental Design Commons, Geographic Information Sciences Commons, Horticulture Commons, Landscape Architecture Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, and the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Recommended Citation Koske, Philip (2013) "Connecting the “Big Easy”: Lessons from the people surrounding the Lafitte Greenway in New Orleans, Louisiana," Proceedings of the Fábos Conference on Landscape and Greenway Planning: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 34. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/fabos/vol4/iss1/34 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the Fábos Conference on Landscape and Greenway Planning by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Koske: Connecting the “Big Easy” Connecting the “Big Easy”: Lessons from the people surrounding the Lafitte Greenway in New Orleans, Louisiana Philip Koske Introduction The 3.1-mile (4.99-kilometer) linear Lafitte Greenway, one of the first revitalization projects since Hurricane Katrina (2005), is designed to become a vibrant bicycle and pedestrian transportation corridor linking users to the world-famous French Quarter and central business district. As an emerging city, New Orleans generally developed sections of swamp land starting near the French Quarter and growing outward in most directions. -

The Documentation of Nineteenth-Century Gardens: an Examination of the New Orleans Notarial Archives

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1994 The Documentation of Nineteenth-Century Gardens: An Examination of the New Orleans Notarial Archives Stephanie Blythe Lewis University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Lewis, Stephanie Blythe, "The Documentation of Nineteenth-Century Gardens: An Examination of the New Orleans Notarial Archives" (1994). Theses (Historic Preservation). 456. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/456 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Lewis, Stephanie Blythe (1994). The Documentation of Nineteenth-Century Gardens: An Examination of the New Orleans Notarial Archives. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/456 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Documentation of Nineteenth-Century Gardens: An Examination of the New Orleans Notarial Archives Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Lewis, Stephanie Blythe (1994). The Documentation of Nineteenth-Century Gardens: An Examination of the New Orleans Notarial -

City of New Orleans Residential Parking Permit (Rpp) Zones

DELGADO CITY PARK COMMUNITY COLLEGE FAIR GROUNDS ZONE 17 RACE COURSE ZONE 12 CITY OF NEW ORLEANS RESIDENTIAL PARKING E L Y PERMIT (RPP) ZONES S 10 I ¨¦§ A ES N RPP Zones Boundary Descriptions: PL F A I N E Zone 1: Yellow (Coliseum Square) AD L E D St. Charles Avenue / Pontchartrain Expwy / S AV Mississippi River / Jackson Avenue A T V S Zone 2: Purple (French Quarter) D North Rampart Street / Esplanade Avenue / A Mississippi River / Iberville Street O R TU B LA Zone 3: Blue NE ZONE 11 South Claiborne Avenue / State Street / V AV Willow Street / Broadway Street A C N AN O AL Zone 4: Red (Upper Audubon) T S LL T St. Charles Avenue / Audubon Street / O Leake Avenue / Cherokee Street R R A 10 Zone 5: Orange (Garden District) C ¨¦§ . S St. Charles Avenue / Jackson Avenue / ZONE 2 Constance Street / Louisiana Avenue Zone 6: Pink (Newcomb Blvd/Maple Area) Willow Street / Tulane University / St. Charles Avenue / South Carrollton Avenue Zone 7: Brown (University) Willow Street / State Street / St. Charles Avenue / Calhoun Street / Loyola University ZONE 18 Zone 9: Gold (Touro Bouligny) ZONE 14 St. Charles Avenue / Louisiana Avenue / Magazine Street / Napoleon Avenue ZONE 3 AV Zone 10: Green (Nashville) NE St. Charles Avenue / Arabella Street / ZONE 6 OR Prytania Street / Exposition Blvd IB LA C Zone 11: Raspberry (Faubourg Marigny) S. TULANE St. Claude Avenue / Elysian Fields Avenue / UNIVERSITY ZONE 16 Mississippi River / Esplanade Avenue ZONE 15 Zone 12: White (Faubourg St. John) DeSaix Blvd / St. Bernard Avenue / LOYOLA N North Broad Street / Ursulines Avenue / R UNIVERSITY A Bell Street / Delgado Drive ZONE 7 P O E L Zone 13: Light Green (Elmwood) E AV ZONE 1 Westbank Expwy / Marr Avenue / O ES V General de Gaulle Drive / Florence Avenue / N L ZONE 4 R Donner Road A HA I V . -

Appraisal of Former Audubon School/ Carrollton Courthouse Property 719 South Carrollton Avenue New Orleans, Louisiana70118

APPRAISAL OF FORMER AUDUBON SCHOOL/ CARROLLTON COURTHOUSE PROPERTY 719 SOUTH CARROLLTON AVENUE NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA70118 FOR MR. LESLIE J. REY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR PURCHASING/ANCILLARY SERVICES & TRANSPORTATION 3520 GENERAL DE GAULLE DRIVE 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 5078 NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA 70053 BY HENRY W. TATJE, III ARGOTE, DERBES & TATJE, LLC REPORT DATE 512 N. CAUSEWAY BLVD NOVEMBER 28, 2016 METAIRIE, LA 70001 504.830.3864 DIRECT LINE OUR FILE NUMBER 504.830.3870 FAX 16-296.003 ARGOTE, DERBES & TATJE, LLC. REAL ESTATE APPRAISAL & COUNSELING 512 N. Causeway Boulevard Metairie, Louisiana 70001 Direct Line: (504) 830-3864 Email: [email protected] November 28, 2016 Our File No. 16-0296.003 Mr. Leslie J. Rey Executive Director Purchasing/Ancillary Services & Transportation 3520 General De Gaulle Drive 5th Floor, Room 5078 New Orleans, Louisiana 70114 RE: Appraisal of Former Audubon School/Carrollton Courthouse Property 719 South Carrollton Avenue New Orleans, Louisiana 70118 Owner: Orleans Parish School Board Dear Mr. Rey: In accordance with your request, I have prepared a real property appraisal of the above-referenced property, presented in a summary appraisal report format. This appraisal report sets forth the most pertinent data gathered, the techniques employed, and the reasoning leading to my opinion of the current market value of the Unencumbered Fee Simple Interest in and to the appraised property in current “As Is Condition”. Market Value, as used herein, is defined as: "The most probable price which a property should bring in a competitive and open market under all conditions requisite to a fair sale, the buyer and seller each acting prudently and knowledgeably, and assuming the price is not affected by undue stimulus." The property rights appraised is the Unencumbered Fee Simple Interest which is defined as: “an absolute fee; a fee without limitations to any particular class of heirs or restrictions, but subject to the limitations of eminent domain, escheat, police power, and taxation. -

Louisiana Sheriffs Partner with State Leaders During Hurricane Gustav and Hurricane Ike

HURRICANES GUSTAV AND IKE Partnerships Through the Storms THE ISIA OU NA L EMBERSH M IP Y P R R A O R G O R N A M O H E ST 94 AB 19 S LISHED ’ HERIFFS The Official Publication of Louisiana's Chief Law Enforcement Officers MARCH 2009 20 th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE SPECIAL EDITION Louisiana Sheriffs Partner with state leaders during Hurricane Gustav and Hurricane Ike Members of the Governor’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness (GOHSEP) Unified Command Group performing statewide recovery efforts after Hurricanes Gustav and Ike. Pictured from left to right are Superintendent of Louisiana State Police, Colo- nel Mike Edmonson; Chief of Staff Timmy Teepell; State Commander Sergeant Major Tommy Caillier; Adjutant General, MG Bennett C. Landreneau; Governor Bobby Jindal; Major Ken Bailie; LSA Executive Director, Hal Turner; Director of GOHSEP, Mark Cooper. Photograph by Danny Jackson, Louisiana Sheriffs’ Association by Lauren Labbé Meher, Louisiana Sheriffs’ Association n August 29, 2008, exactly three years after Hurricane and the length of time it took to travel across the state. Every Katrina, Louisiana residents were facing an all-too-famil- parish in the state was impacted by either tidal surges, flooding, iar situation. Hurricane Gustav was nearing Cuba and, wind damage or power outages. With 74 mph hurricane strength Oaccording to most predictions, heading on a path that led straight wind gusts lingering over the capital city for at least two hours, into the Gulf of Mexico, putting Louisiana in eminent danger. meteorologists claim it was the worst storm to hit the area. -

The Big Easy and All That Jazz

©2014 JCO, Inc. May not be distributed without permission. www.jco-online.com The Big Easy and All that Jazz fter Hurricane Katrina forced a change of A venue to Las Vegas in 2006, the AAO is finally returning to New Orleans April 25-29. While parts of the city have been slow to recover from the disastrous flooding, the main draws for tourists—music, cuisine, and architecture—are thriving. With its unique blend of European, Caribbean, and Southern cultures and styles, New Orleans remains a destination city for travelers from around the United States and abroad. Transportation and Weather The renovated Ernest N. Morial Convention Center opened a new grand entrance and Great Hall in 2013. Its location in the Central Business District is convenient to both the French Quarter Bourbon Street in the French Quarter at night. Photo © Jorg Hackemann, Dreamstime.com. to the north and the Garden District to the south. Museums, galleries, and other attractions, as well as several of the convention hotels, are within Tours walking distance, as is the Riverfront Streetcar line that travels along the Mississippi into the Get to know popular attractions in the city French Quarter. center by using the hop-on-hop-off double-decker Louis Armstrong International Airport is City Sightseeing buses, which make the rounds about 15 miles from the city center. A shuttle with of a dozen attractions and convenient locations service to many hotels is $20 one-way; taxi fares every 30 minutes (daily and weekly passes are are about $35 from the airport, although fares will available). -

Pdf2019.04.08 Fontana V. City of New Orleans.Pdf

Case 2:19-cv-09120 Document 1 Filed 04/08/19 Page 1 of 16 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA LUKE FONTANA, Plaintiff, CIVIL ACTION NO.: v. JUDGE: The CITY OF NEW ORLEANS; MAYOR LATOYA CANTRELL, in her official capacity; MICHAEL HARRISON, FORMER MAGISTRATE JUDGE: SUPERINTENDENT OF THE NEW ORLEANS POLICE DEPARTMENT, in his official capacity; SHAUN FERGUSON, SUPERINTENDENT OF THE NEW ORLEANS POLICE DEPARTMENT, in his official capacity; and NEW ORLEANS POLICE OFFICERS BARRY SCHECHTER, SIDNEY JACKSON, JR. and ANTHONY BAKEWELL, in their official capacities, Defendants. COMPLAINT INTRODUCTION 1. For more than five years, the City of New Orleans (the “City”) has engaged in an effort to stymie free speech in public spaces termed “clean zones.” Beginning with the 2013 Super Bowl, the City has enacted zoning ordinances to temporarily create such “clean zones” in which permits, advertising, business transactions, and commercial activity are strictly prohibited. Clean zones have been enacted for various public events including the 1 Case 2:19-cv-09120 Document 1 Filed 04/08/19 Page 2 of 16 Superbowl, French Quarter Festival, Satchmo Festival and Essence Festival. These zones effectively outlaw the freedom of expression in an effort to protect certain private economic interests. The New Orleans Police Department (“NOPD”) enforces the City’s “clean zones” by arresting persons engaged in public speech perceived as inimical to those interests. 2. During the French Quarter Festival in April 2018, Plaintiff Luke Fontana was doing what he has done for several years: standing behind a display table on the Moonwalk near Jax Brewery by the Mississippi riverfront. -

Urban Public Space, Privatization, and Protest in Louis Armstrong Park and the Treme, New Orleans

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2001 Protecting 'Place' in African -American Neighborhoods: Urban Public Space, Privatization, and Protest in Louis Armstrong Park and the Treme, New Orleans. Michael Eugene Crutcher Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Crutcher, Michael Eugene Jr, "Protecting 'Place' in African -American Neighborhoods: Urban Public Space, Privatization, and Protest in Louis Armstrong Park and the Treme, New Orleans." (2001). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 272. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/272 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

If You Are Interested in Operating a Food Truck in Any of the Yellow Areas

If you are interested in operating a food truck in any of the yellow areas indicated on the City’s Food Truck Operating Areas map*, you must first obtain a City-issued food truck permit (mayoralty permit) and an occu- pational license. This guide will help you understand how to apply, and if you are approved, what general requirements you will need to abide by. *The referenced map is for guidance purposes only. The City shall provide an applicant the specific type of application (permit or franchise) for a specific area. PREREQUISITES FOR APPLICATION: The application process begins with the City’s One Stop for licenses and permits, which is located on the 7th floor of City Hall (1300 Perdido Street). Along with a completed application, on forms provided by the City, you must also have all of the documents, certifications and inspections listed below. No application shall be processed until all required documentation is received. No applicant is guaranteed a Permit. A copy of the mobile food truck’s valid registration with the Louisiana Department of Motor Vehicles. All trucks must be registered in the State of Louisiana. A copy of automobile insurance for the mobile food truck, providing insurance coverage for any automo- bile accident that may occur while driving on the road. A copy of your commercial general liability insurance coverage policy with liability coverage of at least $500,000, naming the City as an insured party, providing insurance coverage for any accident that may occur while selling your food and conducting your business on the public rights-of-ways. -

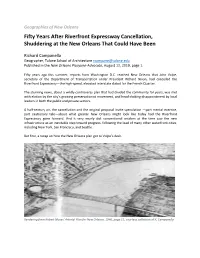

Riverfront Expressway Cancellation, Shuddering at the New Orleans That Could Have Been

Geographies of New Orleans Fifty Years After Riverfront Expressway Cancellation, Shuddering at the New Orleans That Could Have Been Richard Campanella Geographer, Tulane School of Architecture [email protected] Published in the New Orleans Picayune-Advocate, August 12, 2019, page 1. Fifty years ago this summer, reports from Washington D.C. reached New Orleans that John Volpe, secretary of the Department of Transportation under President Richard Nixon, had cancelled the Riverfront Expressway—the high-speed, elevated interstate slated for the French Quarter. The stunning news, about a wildly controversy plan that had divided the community for years, was met with elation by the city’s growing preservationist movement, and head-shaking disappointment by local leaders in both the public and private sectors. A half-century on, the cancellation and the original proposal invite speculation —part mental exercise, part cautionary tale—about what greater New Orleans might look like today had the Riverfront Expressway gone forward. And it very nearly did: conventional wisdom at the time saw the new infrastructure as an inevitable step toward progress, following the lead of many other waterfront cities, including New York, San Francisco, and Seattle. But first, a recap on how the New Orleans plan got to Volpe’s desk. Rendering from Robert Moses' Arterial Plan for New Orleans, 1946, page 11, courtesy collection of R. Campanella The initial concept for the Riverfront Expressway emerged from a post-World War II effort among state and city leaders to modernize New Orleans’ antiquated regional transportation system. Toward that end, the state Department of Highways hired the famous—many would say infamous—New York master planner Robert Moses, who along with Andrews & Clark Consulting Engineers, released in 1946 his Arterial Plan for New Orleans. -

Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 © Copyright by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line by Benjamin Grant Doleac Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Cheryl L. Keyes, Chair The black brass band parade known as the second line has been a staple of New Orleans culture for nearly 150 years. Through more than a century of social, political and demographic upheaval, the second line has persisted as an institution in the city’s black community, with its swinging march beats and emphasis on collective improvisation eventually giving rise to jazz, funk, and a multitude of other popular genres both locally and around the world. More than any other local custom, the second line served as a crucible in which the participatory, syncretic character of black music in New Orleans took shape. While the beat of the second line reverberates far beyond the city limits today, the neighborhoods that provide the parade’s sustenance face grave challenges to their existence. Ten years after Hurricane Katrina tore up the economic and cultural fabric of New Orleans, these largely poor communities are plagued on one side by underfunded schools and internecine violence, and on the other by the rising tide of post-disaster gentrification and the redlining-in- disguise of neoliberal urban policy. -

Collection Uarterly

VOLUME XXXVI The Historic New Orleans NUMBERS 2–3 SPRING–SUMMER Collection uarterly 2019 Shop online at www.hnoc.org/shop VIEUX CARRÉ VISION: 520 Royal Street Opens D The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly ON THE COVER The newly expanded Historic New Orleans B Collection: A) 533 Royal Street, home of the Williams Residence and Louisiana History Galleries; B) 410 Chartres Street, the Williams Research Center; C) 610 Toulouse Street, home to THNOC’s publications, marketing, and education departments; and D) the new exhibition center at 520 Royal Street, comprising the Seignouret- Brulatour Building and Tricentennial Wing. C D photo credit: ©2019 Jackson Hill A CONTENTS 520 ROYAL STREET /4 Track the six-year planning and construction process of the new exhibition center. Take an illustrated tour of 520 Royal Street. Meet some of the center’s designers, builders, and artisans. ON VIEW/18 THNOC launches its first large-scale contemporary art show. French Quarter history gets a new home at 520 Royal Street. Off-Site FROM THE PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT COMMUNITY/28 After six years of intensive planning, archaeological exploration, and construction work, On the Job: Three THNOC staff members as well as countless staff hours, our new exhibition center at 520 Royal Street is now share their work on the new exhibition open to the public, marking the latest chapter in The Historic New Orleans Collection’s center. 53-year romance with the French Quarter. Our original complex across the street at 533 Staff News Royal, anchored by the historic Merieult House, remains home to the Williams Residence Become a Member and Louisiana History Galleries.