Primates in Peril: the World’S 25 Most Endangered Primates 2010–2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lemur News 7 (2002).Pdf

Lemur News Vol. 7, 2002 Page 1 Conservation International’s President EDITORIAL Awarded Brazil’s Highest Honor In recognition of his years of conservation work in Brazil, CI President Russell Mittermeier was awarded the National Are you in favor of conservation? Do you know how conser- Order of the Southern Cross by the Brazilian government. vation is viewed by the academic world? I raise these ques- Dr. Mittermeier received the award on August 29, 2001 at tions because they are central to current issues facing pri- the Brazilian Ambassador's residence in Washington, DC. matology in general and prosimians specifically. The National Order of the Southern Cross was created in The Duke University Primate Center is in danger of being 1922 to recognize the merits of individuals who have helped closed because it is associated with conservation. An inter- to strengthen Brazil's relations with the international com- nal university review in 2001 stated that the Center was too munity. The award is the highest given to a foreign national focused on conservation and not enough on research. The re- for service in Brazil. viewers were all researchers from the "hard" sciences, but For the past three decades, Mittermeier has been a leader in they perceived conservation to be a negative. The Duke ad- promoting biodiversity conservation in Brazil and has con- ministration had similar views and wanted more emphasis ducted numerous studies on primates and other fauna in the on research and less on conservation. The new Director has country. During his time with the World Wildlife Fund three years to make that happen. -

Bangor University DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Impacts of Community Forest Management and Strictly Protected Areas on Deforestation

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Impacts of Community Forest Management and strictly protected areas on deforestation and human well-being in Madagascar Rasolofoson, Ranaivo Award date: 2016 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 08. Oct. 2021 University of Copenhagen Bangor University PhD Thesis Ranaivo Andriarilala Rasolofoson Title: Impacts of Community Forest Management and strictly protected areas on deforestation and human well-being in Madagascar Research progamme: The human dimension of forest conservation: consequences of forest dependence for conservation management Submitted on July 11th, 2016 Author : Ranaivo Andriarilala Rasolofoson Title : Impacts of Community Forest Management and strictly protected -

New Species and Species Reports of Croton L. (Euphorbiaceae) from the Eastern Forest Corridor of Madagascar

New species and species reports of Croton L. (Euphorbiaceae) from the eastern forest corridor of Madagascar Kent Kainulainen, Benjamin van Ee, Patrice Antilahimena, Hanta Razafindraibe & Paul E. Berry Abstract KNUAI LAINEN, K., B. VAN EE, P. ANTILAHIMENA, H. RAZAFINDRAIBE & P.E.BERRY (2016). New species and species reports of Croton L. (Euphorbiaceae) from the eastern forest corridor of Madagascar. Candollea 71 : 327-356. In English, English and French abstracts. DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.15553/c2016v712a17 Six species of Croton from the Moramanga District of the Alaotra-Mangoro Region of eastern Madagascar (Toamasina Prov.) are newly described here, five of which occur in the Ambatovy mining concession. A seventh new species is described from the Ankerana Forest in the Atsinanana Region, some 80 km to the northeast of the town of Moramanga, which is one of the offset areas intended to mitigate the deforestation incurred by the Ambatovy mining project. Of the new species, Croton ferricretus Kainul., B.W. van Ee & P.E. Berry is the one most closely associated with the ultramafic soils where nickel and cobalt is being extracted. Although it is locally common, it is only known from the mine concession. Croton enigmaticus P.E. Berry & B.W. van Ee is considerably less common on the mine concession but is also known from two other sites. Croton droguetioides Kainul. & Radcl.-Sm. is known from Ambatovy and three other areas in the Alaotra-Mangoro Region, and Croton radiatus P.E. Berry & Kainul. is known only from forests on the Ambatovy mining concession and from the area of Zahamena National Park. -

Ecosystem Profile Madagascar and Indian

ECOSYSTEM PROFILE MADAGASCAR AND INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS FINAL VERSION DECEMBER 2014 This version of the Ecosystem Profile, based on the draft approved by the Donor Council of CEPF was finalized in December 2014 to include clearer maps and correct minor errors in Chapter 12 and Annexes Page i Prepared by: Conservation International - Madagascar Under the supervision of: Pierre Carret (CEPF) With technical support from: Moore Center for Science and Oceans - Conservation International Missouri Botanical Garden And support from the Regional Advisory Committee Léon Rajaobelina, Conservation International - Madagascar Richard Hughes, WWF – Western Indian Ocean Edmond Roger, Université d‘Antananarivo, Département de Biologie et Ecologie Végétales Christopher Holmes, WCS – Wildlife Conservation Society Steve Goodman, Vahatra Will Turner, Moore Center for Science and Oceans, Conservation International Ali Mohamed Soilihi, Point focal du FEM, Comores Xavier Luc Duval, Point focal du FEM, Maurice Maurice Loustau-Lalanne, Point focal du FEM, Seychelles Edmée Ralalaharisoa, Point focal du FEM, Madagascar Vikash Tatayah, Mauritian Wildlife Foundation Nirmal Jivan Shah, Nature Seychelles Andry Ralamboson Andriamanga, Alliance Voahary Gasy Idaroussi Hamadi, CNDD- Comores Luc Gigord - Conservatoire botanique du Mascarin, Réunion Claude-Anne Gauthier, Muséum National d‘Histoire Naturelle, Paris Jean-Paul Gaudechoux, Commission de l‘Océan Indien Drafted by the Ecosystem Profiling Team: Pierre Carret (CEPF) Harison Rabarison, Nirhy Rabibisoa, Setra Andriamanaitra, -

2016 Activities Report Wapca in Action Creating Viable Long-Term Solutions

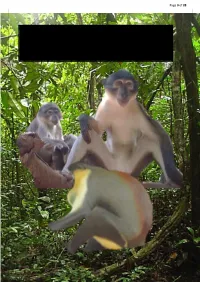

Page 0 of 28 WEST WEST AFRICAN AFRICAN PRIMATE PRIMATE CONSERVATION CONSERVATION ACTION ACTION 2015 Annual Report Annual Report 2016 Annual Report West African Primate Conservation Action Annual Report 2016 Page 1 of 28 WEST AFRICAN PRIMATE CONSERVATION ACTION 2016 ANNUAL REPORT Andrea Dempsey. BA. MSc. Country Coordinator West African Primate Conservation Action P.O. Box GP1319 Accra, Ghana Email: [email protected] Website: www.wapca.org West African Primate Conservation Action Annual Report 2016 Page 2 of 28 Update from the WAPCA-Ghana Country Coordinator WAPCA members, sponsors, partners and friends have continued to generously support us over the past year allowing us to continue the work here in Ghana at both the Critically Endangered Primate Breeding Centre, Kumasi Zoo and also in the field working with communities to protect the forests and the wild primates that inhabit them, for which we are hugely grateful. We’d like to particularly welcome our newest WAPCA member Africa Alive. WAPCA Ghana Board also grew with five new Board members joining – Dr Selorm Tettey, Edward Wiafe, Kwame Tutu, Micheal Abedi-Lartey and Noah Gbexede. The Board also elected David Tettey as our new Chairman. David has been Acting Chairman since the sad passing of our late Chairman – we look forward to him guiding us over the coming years. 2016 saw many visitors – David Morgan from Colchester Zoo, Heather MacIntosh, Hannah Joy and Miranda Crosby from ZSL London Zoo, Tobias Kremer from Heidelberg Zoo, Sabrina Linn from Frankfurt Zoo and Nicky Plaskitt from Paradise Park – I wish to thank them for spending time with our team here and sharing their expertise and knowledge, as well as the useful gifts which they donated including enrichment items donated from Zoo Wizards. -

Habitat Suitability for Primate Conservation in North-East Brazil

Habitat suitability for primate conservation in north-east Brazil B ÁRBARA M ORAES,ORLY R AZGOUR,JOÃO P EDRO S OUZA-ALVES J EAN P. BOUBLI and B RUNA B EZERRA Abstract Brazil has a high diversity of primates, but in- Introduction creasing anthropogenic pressures and climate change could influence forest cover in the country and cause fu- razil is home to species of non-human primates ture changes in the distribution of primate populations. B(Estrada et al., ; Costa-Araújo et al., ; IUCN, Here we aim to assess the long-term suitability of habitats ), of which occur in the Atlantic Forest, Cerrado for the conservation of three threatened Brazilian primates and Caatinga biomes in the north-east. These three biomes (Alouatta belzebul, Sapajus flavius and Sapajus libidinosus) have been extensively modified by centuries of anthropo- through () estimating their current and future distributions genic forest destruction for the development of agriculture, using species distribution models, () evaluating how much infrastructure and urban areas. Primate populations are in of the areas projected to be suitable is represented within sharp decline, including the most charismatic, elusive and protected areas and priority areas for biodiversity conser- rare species. Half of the primate species in north-east Brazil vation, and () assessing the extent of remaining forest cov- are under threat, including five species categorized as er in areas predicted to be suitable for these species. We Endangered and five categorized as Critically Endangered found that % of the suitable areas are outside protected on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN, ). areas and only % are located in areas with forest cover. -

Primate Connections

Primate Connections !"#! Foreword by Dr. Simon Bearder Cover Photo by Noel Rowe THANK YOU! ear Friends, To complete the conservation circle, this DThank you for your support! By purchasing this calendar, you calendar also builds capacity in the places have become part of the Primate Connection – a network of grass where primates need it most. Part of the roots primate conservation organizations working collectively to proceeds from the sale of this calendar are raise awareness about the plight of primates, while generating sent to Oxford Brookes University’s Pri innovative programs that are helping to protect primates throughout mate HabitatCountry Student Scholarship. the world. © Sam Trull This scholarship grants students who come ! "#$%!&'&()*'+,!-'.!/00!10#,.*02!%0*0!3#/!#/402!,'!/%#*0!35,%! from countries where primates live a chance us a synopsis of the conservation issues they face and the creative to receive a Master’s degree in Primate Conservation Biology. ways they go about tackling them. Their renditions, along with A heartfelt thank you is given to those individuals from each photos of some of the rarest and most beautiful primates on the organization that made this project possible: Andrea Donaldson, planet, were then compiled to make this calendar. Helen Thirlway, Shirley McGreal, Steve Coan, Marc Myers, Noel As you read through the pages, you’ll become familiar with Rowe, Lis Key, Aura BeckhoferFialho, Sam Trull, Liz Tyson, Sam some of the most dedicated primate conservation organizations in Shanee, Joy Lliff, Aoife Healy, Pedro MendezCarvajal, Dominique the world. The spectrum of mitigation strategies they employ is both Aubin, Steve Blumkin, Brook Aldrich, Petra Osterberg, Sarah Rus inspiring and vital. -

Online Appendix for “The Impact of the “World's 25 Most Endangered

Online appendix for “The impact of the “World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates” list on scientific publications and media” Table A1. List of species included in the Top25 most endangered primate list from the list of 2000-2002 to 2010-2012 and used in the scientific publication analysis. There is the year of their first mention in the Top25 list and the consecutive mentions in the following Top25 lists. Species names are the current species names (based on IUCN) and not the name used at the time of the Top25 list release. First Second Third Fourth Fifth Sixth Species mention mention mention mention mention mention Ateles fusciceps 2006 Ateles hybridus 2006 2008 2010 Ateles hybridus brunneus 2004 Brachyteles hypoxanthus 2000 2002 2004 Callicebus barbarabrownae 2010 Cebus flavius 2010 Cebus xanthosternos 2000 2002 2004 Cercocebus atys lunulatus 2000 2002 2004 Cercocebus galeritus galeritus 2002 Cercocebus sanjei 2000 2002 2004 Cercopithecus roloway 2002 2006 2008 2010 Cercopithecus sclateri 2000 Eulemur cinereiceps 2004 2006 2008 Eulemur flavifrons 2008 2010 Galagoides rondoensis 2006 2008 2010 Gorilla beringei graueri 2010 Gorilla beringei beringei 2000 2002 2004 Gorilla gorilla diehli 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 Hapalemur aureus 2000 Hapalemur griseus alaotrensis 2000 Hoolock hoolock 2006 2008 Hylobates moloch 2000 Lagothrix flavicauda 2000 2006 2008 2010 Leontopithecus caissara 2000 2002 2004 Leontopithecus chrysopygus 2000 Leontopithecus rosalia 2000 Lepilemur sahamalazensis 2006 Lepilemur septentrionalis 2008 2010 Loris tardigradus nycticeboides -

Laboratory Primate Newsletter

LABORATORY PRIMATE NEWSLETTER Vol. 45, No. 3 July 2006 JUDITH E. SCHRIER, EDITOR JAMES S. HARPER, GORDON J. HANKINSON AND LARRY HULSEBOS, ASSOCIATE EDITORS MORRIS L. POVAR, CONSULTING EDITOR ELVA MATHIESEN, ASSISTANT EDITOR ALLAN M. SCHRIER, FOUNDING EDITOR, 1962-1987 Published Quarterly by the Schrier Research Laboratory Psychology Department, Brown University Providence, Rhode Island ISSN 0023-6861 POLICY STATEMENT The Laboratory Primate Newsletter provides a central source of information about nonhuman primates and re- lated matters to scientists who use these animals in their research and those whose work supports such research. The Newsletter (1) provides information on care and breeding of nonhuman primates for laboratory research, (2) dis- seminates general information and news about the world of primate research (such as announcements of meetings, research projects, sources of information, nomenclature changes), (3) helps meet the special research needs of indi- vidual investigators by publishing requests for research material or for information related to specific research prob- lems, and (4) serves the cause of conservation of nonhuman primates by publishing information on that topic. As a rule, research articles or summaries accepted for the Newsletter have some practical implications or provide general information likely to be of interest to investigators in a variety of areas of primate research. However, special con- sideration will be given to articles containing data on primates not conveniently publishable elsewhere. General descriptions of current research projects on primates will also be welcome. The Newsletter appears quarterly and is intended primarily for persons doing research with nonhuman primates. Back issues may be purchased for $5.00 each. -

Annual Report 2013

H E L P S I M Annual U Report 2013 S ©F-G. Grandin The President’s message In 2013 we continued to support our two major projects: the “Bamboo Lemur” project and the “Ramaimbangy” project. Last year marked a turning point in the involvement of our Association in the “Bamboo Lemur” project: since it became the co-coordinator of the project in 2012, our Association has been very active in the scientific programme, supervising and financing 4 field studies which improved our knowledge about lemurs and human populations living alongside them. 2013 has also seen several educational projects coming to fruition: the construction of two schools in Vohitrarivo and Sahofika, as well as the organization of the “Simus Festival”. The Helpsimus team has expanded in France and consolidated in Madagascar with the official appointment of Nary as our local representative, thus allowing our activities to be developed on the “Bamboo Lemur” project site. I wish to thank warmly our generous donors and our members without whom none of this would have been possible. There is still much to do, but together we can change things! Delphine Roullet Helpsimus President www.helpsimus.org The greater bamboo lemur Prolemur simus • Distribution: eastern Madagascar. • Global population in the wild: slightly more than 600 individuals, most of them living outside protected areas. • Diet: folivorous (bamboo). • Social system: fission-fusion, but little existing data. • IUCN status: critically endangered. ©F-G. Grandin Helpsimus Association Française pour la Sauvegarde du Grand Hapalémur (AFSGH) French Association for the Protection of the Greater Bamboo Lemur Key dates: • 2008: the (future) president met the local stakeholders involved in conserving the greater bamboo lemur in Madagascar. -

Approaching Local Perceptions of Forest Governance and Livelihood Challenges with Companion Modeling from a Case Study Around Zahamena National Park, Madagascar

Research Collection Journal Article Approaching local perceptions of forest governance and livelihood challenges with companion modeling from a case study around Zahamena National Park, Madagascar Author(s): Bodonirina, Nathalie; Reibelt, Lena M.; Stoudmann, Natasha; Chamagne, Juliette; Jones, Trevor G.; Ravaka, Annick; Ranjaharivelo, Hoby V.F.; Ravonimanantsoa, Tantelinirina; Moser, Gabrielle; De Grave, Arnaud; Garcia, Claude; Ramamonjisoa, Bruno; Wilmé, Lucienne; Waeber, Patrick O. Publication Date: 2018-10-10 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000302488 Originally published in: Forests 9(10), http://doi.org/10.3390/f9100624 Rights / License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library Article Approaching Local Perceptions of Forest Governance and Livelihood Challenges with Companion Modeling from a Case Study around Zahamena National Park, Madagascar Nathalie Bodonirina 1, Lena M. Reibelt 2 , Natasha Stoudmann 3, Juliette Chamagne 3, Trevor G. Jones 4, Annick Ravaka 1 , Hoby V. F. Ranjaharivelo 1, Tantelinirina Ravonimanantsoa 1, Gabrielle Moser 3, Arnaud De Grave 5, Claude Garcia 3,6 , Bruno S. Ramamonjisoa 1, Lucienne Wilmé 7,8 and Patrick O. Waeber 3,* 1 ESSA Forêts, Ankatso, BP 175, Antananarivo 101, Madagascar; [email protected] (N.B.); [email protected] (A.R.); [email protected] (H.V.F.R.); [email protected] (T.R.); [email protected] -

World's Most Endangered Primates

Primates in Peril The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018 Edited by Christoph Schwitzer, Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands, Federica Chiozza, Elizabeth A. Williamson, Elizabeth J. Macfie, Janette Wallis and Alison Cotton Illustrations by Stephen D. Nash IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG) International Primatological Society (IPS) Conservation International (CI) Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Published by: IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), Bristol Zoological Society (BZS) Copyright: ©2017 Conservation International All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Inquiries to the publisher should be directed to the following address: Russell A. Mittermeier, Chair, IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group, Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, VA 22202, USA. Citation (report): Schwitzer, C., Mittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B., Chiozza, F., Williamson, E.A., Macfie, E.J., Wallis, J. and Cotton, A. (eds.). 2017. Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA. 99 pp. Citation (species): Salmona, J., Patel, E.R., Chikhi, L. and Banks, M.A. 2017. Propithecus perrieri (Lavauden, 1931). In: C. Schwitzer, R.A. Mittermeier, A.B. Rylands, F. Chiozza, E.A. Williamson, E.J. Macfie, J. Wallis and A. Cotton (eds.), Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2016–2018, pp. 40-43. IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG), International Primatological Society (IPS), Conservation International (CI), and Bristol Zoological Society, Arlington, VA.