Outward Bound with Ayyappan: Work, Masculinity, and Self-Respect in a South Indian Pilgrimage Festival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Kingdom of Nataraja, a Guide to the Temples, Beliefs and People of Tamil Nadu

* In the Kingdom of Nataraja, a guide to the temples, beliefs and people of Tamil Nadu The South India Saiva Siddhantha Works Publishing Society, Tinnevelly, Ltd, Madras, 1993. I.S.B.N.: 0-9661496-2-9 Copyright © 1993 Chantal Boulanger. All rights reserved. This book is in shareware. You may read it or print it for your personal use if you pay the contribution. This document may not be included in any for-profit compilation or bundled with any other for-profit package, except with prior written consent from the author, Chantal Boulanger. This document may be distributed freely on on-line services and by users groups, except where noted above, provided it is distributed unmodified. Except for what is specified above, no part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system - except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review to be printed in a magazine or newspaper - without permission in writing from the author. It may not be sold for profit or included with other software, products, publications, or services which are sold for profit without the permission of the author. You expressly acknowledge and agree that use of this document is at your exclusive risk. It is provided “AS IS” and without any warranty of any kind, expressed or implied, including, but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose. If you wish to include this book on a CD-ROM as part of a freeware/shareware collection, Web browser or book, I ask that you send me a complimentary copy of the product to my address. -

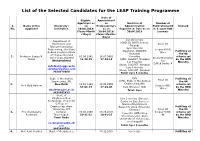

List of the Selected Candidates for the LEAP Training Programme

List of the Selected Candidates for the LEAP Training Programme Date of Eligible Appointment Age/58yrs as as Duration of Number of S. Name of the University / on Professor/8yrs Administrative Publications/30 Remark No. Applicant Institution 30.04.2019/ as on Experience/ 3yrs as on in Scopus-UGC (Years-Month 30.04.2019/ 30.04.2019 Journals s-Days) (Years-Months- Days) 1yr 10 months Department of (HOD, Dr. BATU, Lonere, Electronics and Total: 76 Raigad) Telecommunication 2yrs 8months Engineering, Shri Guru Scopus+UGC: (Registrar, SGGSIET, Fulfilling all Gobind Singhji Institute 30++ Nanded) the 04 of Engineering and 1. Professor Sanjay N. 01.06.1962 16.07.2001 8 months criteria set Technology, Nanded Books/Monograp Talbar 56-10-29 17-09-14 (HOD, SGGSIET, Nanded) by the HRD (Maharashtra) hs/ 1yr 7months Ministry Edited Books: 8 (Dean, SGGSIET, Nanded) [email protected] 1yrs 8 months [email protected] (Dean, SGGSIET, Nanded) 9850978050 Total: 8yrs 5 months Dept. of Mechanical 3yrs Fulfilling all Total: 95 Engineering, JMI, (HOD, Dept. of Mechanical the 04 2. New Delhi 11.02.1962 25.01.2002 Engineering, JMI) criteria set Prof. Abid Haleem Scopus-UGC: 57-02-19 17-03-05 5yrs (Director, IQA) by the HRD 30++ [email protected] Total: 8yrs Ministry 9818501633 Dept. of Pharmaceutical 5yrs 3 months (Director, Technology, University Centre for Excellence in College of NanobioTranslational Engineering, Anna Research, Anna University, Fulfilling all University, BIT Chennai) Total: 96 the 04 3. Prof. Kandasamy Campus, 08.05.1968 05.03.2005 Scopus+UGC: criteria set 5 months (Officiating Ruckmani Tiruchirapalli, 50-11-22 14-01-25 96 by the HRD Vice-Chancellor, Anna Tamil Nadu Ministry University of Technology, Tiruchirapalli) [email protected] u.in Total: 5yrs 8 months 9842484568 4. -

Affidavit of Thiruvannamalai Municipality

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION S. L. P. (CIVIL) Nos. 12443-12447 OF 2001 IN THE MATTER OF: Commissioner: Thiruvannamalai Municipality Petitioner Versus Arunachala Giri Pradakshana Samithi and others Respondents AFFIDAVIT ON BEHALF OF THE PETITIONER IN RESPONSE TO THE AFFIDAVIT OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA – GOVERNMENT OF INDIA DEPOSED TO BY Dr. K.P. PUNACHA PURSUANT TO THE ORDERS DATED 20.01.2005 OF THIS HON’BLE COURT I, V. Akbar, aged about 56 years, son of Shri Abdul Sahib, Commissioner of Thiruvannamalai Municipality, Tamil Nadu, presently at New Delhi, do hereby solemnly affirm and state as follows: 1. I state that I am the Commissioner of the Thiruvannamalai Municipality, the petitioner herein and am conversant with the facts of the case as borne out from the records, and as such, I am competent to swear this affidavit. I state that I have read a copy of the aforesaid affidavit and in response thereto, I am instructed to state as under: 2. Before adverting to the proposals made and positions adopted by the Government of India in the aforesaid affidavit, I seek to place certain preliminary and essential facts on record. These are: (i) That Thiruvannamalai is a popular temple town in Tamil Nadu. It is connected to other towns by nine entry roads which converge on its main street called ‘Car Street’ that travels along the ‘girivalam’ or ‘giri pradakshina path’ for about 4 kms., through the centre of the town. Thiruvannamalai is a Municipality established under the Tamil Nadu District Municipalities Act, 1920 (hereinafter ‘Municipal Act’). -

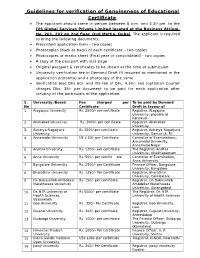

Guidelines for Verification of Genuineness of Educational Certificate the Applicant Should Come in Person Between 8 A.M

Guidelines for verification of Genuineness of Educational Certificate The applicant should come in person between 8 a.m. and 3.30 pm. to the IVS Global Services Private Limited located at the Business Atrium, No. 201, 202 on 2nd floor, Oud Metha, Dubai . The applicant is required to bring the following documents. Prescribed application form – two copies Photocopies (back to back) of each certificate – two copies Photocopies of marks sheet (Final year or consolidated) - two copies A copy of the passport with visa page Original passport & certificates to be shown at the time of submission University verification fee in Demand Draft (If required as mentioned in the application proforma) and a photocopy of the same Verification fees Dhs 60/- and IVS fee of Dhs. 4.50/- and (optional) Courier charges Dhs. 35/- per document to be paid for each application after scrutiny of the particulars of the application. S. University /Board Fee charged per To be paid by Demand No Certificate Draft in favour of 1 Alagappa University Rs. 2500/- per certificate Registrar, Alagappa University, payable at Karaikudi 2. Allahabad University Rs. 2000/- per certificate Registrar, Allahabad University 3. Acharya Nagarjuna Rs.1500/-per certificate Registrar, Acharya Nagarjuna University University, Gantur (A. P.) 4 Annamalai University US $ 50/- per Certificate Controller of Examinations, Annamalai University, Annamalai Nagar 5 Andhra University Rs. 1200/- per certificate The Registrar, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam 6 Anna University Rs. 500/- per certific ate Controller of Examination, Anna University 7 Bangalore University Rs. 2500/- per Certificate Finance Officer, Bangalore University, Bangalore 8 Bharathiar University Rs. 1250/- Per Certificate Registrar, Bharathiar University, Coimbatore 9 Dr. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Dated : 23/4/2016

Dated : 23/4/2016 Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name Defaulting Year 01750017 DUA INDRAPAL MEHERDEEP U72200MH2008PTC184785 ALFA-I BPO SERVICES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750020 ARAVIND MYLSWAMY U01120TZ2008PTC014531 M J A AGRO FARMS PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750025 GOYAL HEMA U18263DL1989PLC037514 LEISURE WEAR EXPORTS 2007-08 LTD. 01750030 MYLSWAMY VIGNESH U01120TZ2008PTC014532 M J V AGRO FARM PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750033 HARAGADDE KUMAR U74910KA2007PTC043849 HAVEY PLACEMENT AND IT 2008-09, 2009-10 SHARATH VENKATESH SOLUTIONS (INDIA) PRIVATE 01750063 BHUPINDER DUA KAUR U72200MH2008PTC184785 ALFA-I BPO SERVICES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750107 GOYAL VEENA U18263DL1989PLC037514 LEISURE WEAR EXPORTS 2007-08 LTD. 01750125 ANEES SAAD U55101KA2004PTC034189 RAHMANIA HOTELS 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750125 ANEES SAAD U15400KA2007PTC044380 FRESCO FOODS PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750188 DUA INDRAPAL SINGH U72200MH2008PTC184785 ALFA-I BPO SERVICES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750202 KUMAR SHILENDRA U45400UP2007PTC034093 ASHOK THEKEDAR PRIVATE 2008-09, 2009-10 LIMITED 01750208 BANKTESHWAR SINGH U14101MP2004PTC016348 PASHUPATI MARBLES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750212 BIAPPU MADHU SREEVANI U74900TG2008PTC060703 SCALAR ENTERPRISES 2009-10 PRIVATE LIMITED 01750259 GANGAVARAM REDDY U45209TG2007PTC055883 S.K.R. INFRASTRUCTURE 2008-09, 2009-10 SUNEETHA AND PROJECTS PRIVATE 01750272 MUTHYALA RAMANA U51900TG2007PTC055758 NAGRAMAK IMPORTS AND 2008-09, 2009-10 EXPORTS PRIVATE LIMITED 01750286 DUA GAGAN NARAYAN U74120DL2007PTC169008 -

Phychochemical Composition on Three Species of Sargassum from Southeast Coast of Tamil Nadu, India

Plant Archives Vol. 20 Supplement 1, 2020 pp. 1555-1559 e-ISSN:2581-6063 (online), ISSN:0972-5210 PHYCHOCHEMICAL COMPOSITION ON THREE SPECIES OF SARGASSUM FROM SOUTHEAST COAST OF TAMIL NADU, INDIA K. Murugaiyan Department of Botany, Annamalai University, Annamalai Nagar-608002 (Tamil Nadu) India. Abstract Phycochemical studies on three species of Sargassum have been made to understand which is the most important and useful for mariculture. The species studied were Sargassum ilicifolium, Sargassum liniarifolium and Sargassum polycystum. Phycochemical studies such as the amount of protein, amino acids, carbohydrate and iodine have been made for comparison. Macro-elements such as Nitrogen, Phosphate and Potash and micro-elements like Calcium, magnesium and Iron have been made for interrelationship among the taxa. The amount of iodine (206.08 mg/100 g) in Sargassum ilicifolium was higher than the other two species. The amount of protein (44.4 mg/g f.w) in Sargassum liniarifolium was higher whereas the amount of amino acids (0.45 mg/g f.w) was high in Sargassum ilicifolium. But the total sugar (0.67 mg/g f.w) in S. polycystum showed maximum value. With reference to micro and macroelements, Sargassum ilicifolium showed maximum values. The phycochemical studies of the three species showed better result in Sargassum ilicifolium and this may be a good species for Mariculture. Key word: Phycochemical, Macro element, Microelement, Macro algae, Sargassum, Southeast Coast, Rameswaram. Introduction a concentration much higher than in terrestrial plants. Seaweeds are one of the most important marine They also contain protein, iodine, bromine, vitamins and resources of the world and being used as human food, substances of stimulatory and antibiotic nature. -

Annamalai Hi Coimbatore Research Article Ical

z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 10, Issue, 05, pp.69328-69340, May, 2018 ISSN: 0975-833X RESEARCH ARTICLE AN ETHNOBOTANICAL STUDY OF MEDICINAL PLANTS USED BY LOCAL PEOPLE AND TRIBALS IN TOPSLIP (ANNAMALAI HILLS) AND OOTY (CHINCHONA VILLAGE) OF COIMBATORE AND OOTY DISTRICT 1Satheesh Kumar, A., *2Sankaranarayanan, S., 3Bama, P., 4Baskar, R. and 4Kanagavalli, K. 1Department of Medicinal Botany, Government Siddha Medical College, Arumbakkam, Chennai 600 106, Tamil Nadu, India 2Department of Nanju nool (Toxicology), Government Siddha Medical College, Arumbakkam, Chennai 600 106, Tamil Nadu, India 3Department of Noinadal (Pathalogy), Government Siddha Medical College, Arumbakkam, Chennai 600 106, Tamil Nadu, India 4Department of Medicine, Government Siddha Medical College, Arumbakkam, Chennai 600 106, Tamil Nadu, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: An ethno botanical study was carried out to collect evidence on the use of medicinal plants by the Received 21st February, 2018 people who live in Topslip and Ooty Taluk of Coimbatore and Ooty district, Tamil Nadu. This study Received in revised form designed to identify plants collected for medicinal purposes by the local people and tribals of Topslip 19th March, 2018 and Ooty, located in the Coimbatore and Ooty district of Tamil Nadu and to document the traditional Accepted 29th April, 2018 names, preparation and uses of these plants. This is the first ethnobotanical study in which statistical Published online 30th May, 2018 calculations about plants are done by ICF (Informant Consensus Factor) method. Field research was conducted by collecting ethno botanical information during structured and semi-structured interviews Key words: with native knowledgeable people in region. -

Freedom of Religion and the Indian Supreme Court: The

FREEDOM OF RELIGION AND THE INDIAN SUPREME COURT: THE RELIGIOUS DENOMINATION AND ESSENTIAL PRACTICES TESTS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN RELIGION MAY 2019 By Coleman D. Williams Thesis Committee: Ramdas Lamb, Chairperson Helen Baroni Ned Bertz Abstract As a religiously diverse society and self-proclaimed secular state, India is an ideal setting to explore the complex and often controversial intersections between religion and law. The religious freedom clauses of the Indian Constitution allow for the state to regulate and restrict certain activities associated with religious practice. By interpreting the constitutional provisions for religious freedom, the judiciary plays an important role in determining the extent to which the state can lawfully regulate religious affairs. This thesis seeks to historicize the related development of two jurisprudential tests employed by the Supreme Court of India: the religious denomination test and the essential practices test. The religious denomination test gives the Court the authority to determine which groups constitute religious denominations, and therefore, qualify for legal protection. The essential practices test limits the constitutional protection of religious practices to those that are deemed ‘essential’ to the respective faith. From their origins in the 1950s up to their application in contemporary cases on religious freedom, these two tests have served to limit the scope of legal protection under the Constitution and legitimize the interventionist tendencies of the Indian state. Additionally, this thesis will discuss the principles behind the operation of the two tests, their most prominent criticisms, and the potential implications of the Court’s approach. -

St. Joseph's Journal of Humanities and Science ISSN: 2347 - 5331

K. Karthikeyan / St. Joseph’s Journal of Humanities and Science (Volume 2 Issue 2 August 2015) 33-37 33 St. Joseph’s Journal of Humanities and Science (Volume 2 Issue 2 August 2015) 33-37 St. Joseph's Journal of Humanities and Science ISSN: 2347 - 5331 http://sjctnc.edu.in/6107-2/ RELIGIOUS TOURIST PLACES IN TIRUVANNAMALAI – A STUDY - K. Karthikeyan* ABSTRACT Tiruvannamalai is a town in the state of Tamilnadu, administrated by a special grade municipality that covers an area of 16.33 km2 (6.31 sq.m) and had a population of 144,278 in 2011. It is the administrative headquarters of Tiruvannamalai District. Located on the foothills of Annamalai. Tiruvannamalai has been ruled by the Pallavas, the Cholas, Hoysalas, the Vijayanagar Empire, the Carnetic Kingdom, Tipu sultan, and the British. It served as the capital city of the Hoysalas. The town is built around the Annamalaiyar Temple. INTRODUCTION Tiruvannamalai is an ancient temple town in TamilNadu with a unique historical back ground. The Tiruvannamalai is named after the central deity of the four great Tamil saivaite poets Sambandar, Sundarar, Annamalaiyar Temple. The Karthigai Deepam festival Appar and Manickavasagar have written about the is celebrated during the day of the full moon between history of Tiruvannamalai in their literary work November and December, and a huge beacon is lit Thevaram and Thiruvasagam which stands unparalleled, atop the Annamalai hill. The event is witnessed by Arunagirinathar has also written beautifully about three million pilgrims. On the day preceding each full the Tiruvannamalai and its Lord Arunachalaeswarar moon, pilgrims circumnavigate the temple base and the temple. -

AND IT's CONTACT NUMBER Tirunelveli 0462

IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS AND EMERGENCY OPERATION CENTRE (EOC) AND IT’S CONTACT NUMBER Name of the Office Office No. Collector’s Office Control Room 0462-2501032-35 Collector’s Office Toll Free No. 1077 Revenue Divisional Officer, Tirunelveli 0462-2501333 Revenue Divisional Officer, Cheranmahadevi 04634-260124 Tirunelveli 0462 – 2333169 Manur 0462 - 2485100 Palayamkottai 0462 - 2500086 Cheranmahadevi 04634 - 260007 Ambasamudram 04634- 250348 Nanguneri 04635 - 250123 Radhapuram 04637 – 254122 Tisaiyanvilai 04637 – 271001 1 TALUK TAHSILDAR Taluk Tahsildars Office No. Residence No. Mobile No. Tirunelveli 0462-2333169 9047623095 9445000671 Manoor 0462-2485100 - 9865667952 Palayamkottai 0462-2500086 - 9445000669 Ambasamudram 04634-250348 04634-250313 9445000672 Cheranmahadevi 04634-260007 - 9486428089 Nanguneri 04635-250123 04635-250132 9445000673 Radhapuram 04637-254122 04637-254140 9445000674 Tisaiyanvilai 04637-271001 - 9442949407 2 jpUney;Ntyp khtl;lj;jpy; cs;s midj;J tl;lhl;rpah; mYtyfq;fspd; rpwg;G nray;ghl;L ikaq;fspd; njhiyNgrp vz;fs; kw;Wk; ,izatop njhiyNgrp vz;fs; tpguk; fPo;f;fz;lthW ngwg;gl;Ls;sJ. Sl. Mobile No. with Details Land Line No No. Whatsapp facility 0462 - 2501070 6374001902 District EOC 0462 – 2501012 6374013254 Toll Free No 1077 1 Tirunelveli 0462 – 2333169 9944871001 2 Manur 0462 - 2485100 9442329061 3 Palayamkottai 0462 - 2501469 6381527044 4 Cheranmahadevi 04634 - 260007 9597840056 5 Ambasamudram 04634- 250348 9442907935 6 Nanguneri 04635 - 250123 8248774300 7 Radhapuram 04637 – 254122 9444042534 8 Tisaiyanvilai 04637 – 271001 9940226725 3 K¡»a Jiw¤ jiyt®fë‹ bršngh‹ v§fŸ mYtyf vz; 1. kht£l M£Á¤ jiyt®, ÂUbešntè 9444185000 2. kht£l tUthŒ mYty®, ÂUbešntè 9445000928 3. khefu fhtš Miza®, ÂUbešntè 9498199499 0462-2970160 4. kht£l fhtš f§fhâ¥ghs®, ÂUbešntè 9445914411 0462-2568025 5. -

Hinduism, the Misunderstood Religion

399 HINDUISM, THE MISUNDERSTOOD RELIGION NALLUSAMY, Kanthasamy MALEZYA/MALAYSIA/МАЛАЙЗИЯ ABSTRACT Hinduism is one of the world’s oldest religions. This faith has faced many ups and downs during the passage of time. However, the theological and philosophical aspects of Hinduism together with the concept of God as the Almighty had made it easier to survive. But in recent times, Hinduism has been misunderstood not only by the followers of other faiths but some of the Hindus themselves. The basic concepts of God, Soul and Bondage or technically, pati, pacu and paca have not been clearly understood. There is only one God but the concept of multiplicity has not been fully understood. The relationship of God with the soul and likewise the relationship of the soul with mala or impurities also have been often wrongly interpreted. The concept of anava, karma and maya in the religion is to assist Hindus in the right path and not a hindrance to their life. This paper thus focuses on the various aspects which the followers have misunderstood the religion. The practicality of the religion, especially during festivals and religious programs, often contradicts with the basic tenets of Hinduism. Motivational talks with the religious themes often tend to give false ideas which clearly not present within the framework of Hinduism. Such attempts may affect the purity and the sacred teachings of Hinduism. Key Words: Hinduism, religion. Introduction Among the religions practised in the world today, Hinduism has an antiquity of many years. Till today, there are no accurate or written documents to prove when Hinduism actually came into being.