1 Danish Ex-Colony Travel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

321 M. Naum and J.M. Nordin (Eds.), Scandinavian Colonialism and the Rise of Modernity: Small Time Agents in a Global Arena

Index A Swedish iron Almenn landskipunarfræði , 40 Board of Mines , 55 Amina revolt global integration , 55 Aquambo nation , 266 market economy , 54 ethnic networks , 264 metal trades , 54 French soldiers , 264 Moravian mission , 265 rebels , 264 B 1733 revolt , 265 Bankhus site , 288–289 Slave Coast , 265 Berckentin Palace , 9 St. Thomas , 263 Brevis Commentarius de Islandia , 39 Atlantic economy Gammelbo to Calabar African traders , 59 C European slave trade and New World Charlotte Amalie port slavery , 60 archaeological exploration , 280 Gammelbo forgemen , 58 Bankhus site , 288–289 slave ships , 59 Caribbean market , 276 voyage iron , 58 cast iron , 279 ironworks Danish trade , 275 Bergslagen region , 55 historical documents , 276 bergsmän , 56 housing compounds, Government Hill , 279 bruks , 56 Magens House site Dannemora mine , 57 ceramics , 284 Dutch and British consumers , 58 Crown House , 283 osmund iron , 56 Danish fl uted lace porcelain , 284 pig iron , 56 excavated material remains , 285 Leufsta to Birmingham’s steel furnaces high-cost goods , 286 British manufacturers market , 64 ironwork , 286 common iron , 61 Moravian ware , 284 international market , 63 terraces , 285 iron quality , 64 urban garden , 287 järnboden storehouse , 63 nineteenth-century gates , 281 Öregrund Iron , 62 spatial analysis Walloon forging technique , 61 Blackbeard’s Castle , 282 Swedish economy , 64–66 bone button blanks , 283 M. Naum and J.M. Nordin (eds.), Scandinavian Colonialism and the Rise of Modernity: 321 Small Time Agents in a Global Arena, Contributions To Global Historical Archaeology 37, DOI 10.1007/978-1-4614-6202-6, © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 322 Index Charlotte Amalie port (cont.) Greenland , 107–108 cultural meaning and intentions , 281 illegal trade interisland trade of goods and alcoholic beverages , 109 wares , 282 British faience plate , 109 social relations , 281 buy and discard practice , 110 transhipment/redistribution centre , 283 Disko Bay , 108 St. -

Nagapattinam District 64

COASTAL DISTRICT PROFILES OF TAMIL NADU ENVIS CENTRE Department of Environment Government of Tamil Nadu Prepared by Suganthi Devadason Marine Research Institute No, 44, Beach Road, Tuticorin -628001 Sl.No Contents Page No 1. THIRUVALLUR DISTRICT 1 2. CHENNAI DISTRICT 16 3. KANCHIPURAM DISTRICT 28 4. VILLUPURAM DISTRICT 38 5. CUDDALORE DISTRICT 50 6. NAGAPATTINAM DISTRICT 64 7. THIRUVARUR DISTRICT 83 8. THANJAVUR DISTRICT 93 9. PUDUKOTTAI DISTRICT 109 10. RAMANATHAPURAM DISTRICT 123 11. THOOTHUKUDI DISTRICT 140 12. TIRUNELVELI DISTRICT 153 13. KANYAKUMARI DISTRICT 174 THIRUVALLUR DISTRICT THIRUVALLUR DISTRICT 1. Introduction district in the South, Vellore district in the West, Bay of Bengal in the East and i) Geographical location of the district Andhra Pradesh State in the North. The district spreads over an area of about 3422 Thiruvallur district, a newly formed Sq.km. district bifurcated from the erstwhile Chengalpattu district (on 1st January ii) Administrative profile (taluks / 1997), is located in the North Eastern part of villages) Tamil Nadu between 12°15' and 13°15' North and 79°15' and 80°20' East. The The following image shows the district is surrounded by Kancheepuram administrative profile of the district. Tiruvallur District Map iii) Meteorological information (rainfall / ii) Agriculture and horticulture (crops climate details) cultivated) The climate of the district is moderate The main occupation of the district is agriculture and allied activities. Nearly 47% neither too hot nor too cold but humidity is of the total work force is engaged in the considerable. Both the monsoons occur and agricultural sector. Around 86% of the total in summer heat is considerably mitigated in population is in rural areas engaged in the coastal areas by sea breeze. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette Extraordinary

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2012 [Price : Rs. 1.60 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 4] CHENNAI, TUESDAY, JANUARY 3, 2012 Margazhi 18, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2042 Part II—Section 2 Notifications or Orders of interest to a section of the public issued by Secretariat Departments. NOTIFICATIONS BY GOVERNMENT HIGHWAYS AND MINOR PORTS DEPARTMENT DECLARATION OF NEW PORTS ARE TO BE CONSOLIDATED INCORPORATING ALL THE PORT LIMITS OF THE EXISTING MINOR PORTS IN TAMIL NADU UNDER INDIAN PORTS ACT, 1908. Amendment to Notifications [G. O. Ms. No. 1, Highways & Minor Ports (HF2), 3rd January 2012.] No. II(2)/HWMP/(c-1)/2012. In exercise of the powers conferred by clause (a) of sub-section (1) and sub-section (2) of Section 4 of the Indian Ports Act, 1908 (Central Act XV of 1908), the Governor of Tamil Nadu hereby extends with effect on and from the 3rd January 2012 the provisions of the said Act to Chettinad Tharangambadi Port in Nagapattinam district in the State of Tamil Nadu and makes the following amendment to the Highways and Minor Ports Department Notification No. II(2)/HWMP/359/2009, published at pages 232-234 of Part II—Section 2 of the Tamil Nadu Government Gazette, dated the 22nd July 2009, as subsequently amended. AMENDMENT In the said Notification, in the Schedule under the heading - "NAGAPATTINAM DISTRICT", after "Serial No. 9B" in column (1) and the corresponding entries in columns (2) and (3) thereof, the following entries shall, respectively, be inserted, namely:— 9 (C) Chettinad 1 Latitude 11º 03' 12" N Tharangambadi Longitude 79º 51' 21" E 2 Latitude 11º 03' 13" N Longitude 79º 53' 32" E 3 Latitude 11º 02' 46" N Longitude 79º 53' 32" E 4 Latitude 11º 02' 46" N Longitude 79º 51' 20" E DTP—II-2 Ex. -

Tamil Development, Religious Endowments and Information Department

Tamil Development, Religious Endowments and Information Department Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Department Demand No.47 Policy Note 2012-2013 Index Page S. No. Subject No. 1 Introduction 1 2 Administration 3 3 Hindu Religious Institutions 4 4 Classification Of The Hindu Religious 4 Institutions 5 Administrative Structure 5 6 Regional And District Administration 8 7 Inspectors 12 ii Page S. No. Subject No. 8 Personal Assistants 12 9 Verification Officers 13 10 Audit Officers 13 11 Senior Accounts Officers 13 12 Engineers 14 13 Executive Officers 16 14 The Administration Of Mutts 17 15 High Level Advisory Committee 17 16 Appointment Of Trustees 18 17 Jurisdiction 19 18 Appointment Of Fit Person 21 19 Land Administration 21 20 Fixation Of Fair Rent 22 21 Revenue Courts 23 22 Retrieval Of Lands 24 23 Removal Of Encroachments 25 iii Page S. No. Subject No. 24 Regularizing The Group 25 Encroachments 25 Annadhana Scheme 26 26 Spiritual And Moral Classes 28 27 Special Poojas And Common Feasts 28 28 Elephant Rejuvenation Camps 29 29 Marriage Scheme For Poor And 30 Downtrodden 30 Cable Cars 31 31 Battery Cars 32 32 Thiruppani 33 33 Donation 34 34 Temple Funds 35 35 Diversion Of Funds 35 36 Government Grant 35 37 Common Good Fund 36 38 Temple Development Fund 36 iv Page S. No. Subject No. 39 Village Temples Renovation Fund 37 40 Temple Renovation And Charitable 37 Fund 41 Donor Works 38 42 Renovation For The Temples In The 38 Habitations Of Adi Dravida And Tribal Community 43 Finance Commission Fund 39 44 Tourism Fund 39 45 Uzhavarapani 40 46 Consecration Of Temples 41 47 Renovation Of Temple Tanks And 42 Rain Water Harvesting 48 Revival Of Kaala Poojas In Ancient 43 Temples 49 Oru Kaala Pooja Scheme 43 50 Maintanence Of Temple Cars 45 v Page S. -

Cyclone and Its Effect on Shoreline Changes in Archaeological Sites, East Coast of Tamil Nadu, India

AEGAEUM JOURNAL ISSN NO: 0776-3808 Cyclone and its Effect on Shoreline Changes in Archaeological Sites, East Coast of Tamil Nadu, India Sathiyamoorthy G, *Sivaprakasam Vasudevan, Selvaganapathi R & Nishikanth C. V Department of Earth Sciences, Annamalai University, Annamalainagar, Tamil Nadu, India. *[email protected] ABSTRACT : The contact line between sea and land, is knows as shoreline and they are experiencing changes due to the long-shore current, tides, wave, and storm surges, etc. The Shorelines played a major role in human settlement and favours the clustering of Port cities from ancient to present. The changes in the shoreline directly affect the livelihood of the coastal cities and also worn out the maritime archaeological sites, particularly during the late Quaternary period. A few archaeological sites including Arikamedu, Poompuhar, Tharangambadi, and Sembiyankandiyur show a direct/indirect relationship with the shoreline changes between 1972 and 2018. The shoreline changes between Pondicherry and Nagapattinam patch, with respect to the archaeological sites, quantify erosion -20.52 m/period in Arikamedu, Poompuhar, and Tharangambadi and -25.28 m/period along Sembiyankandiyur region during a span of 46 years. The maritime Archaeological, pride sites like Poompuhar, Tharangambadi and Sembiyankandiyur on the coastal region were submerged in the sea, the remand parts are also under the threat to vanish at a faster rate. Keywords: LRR, EPR and NSM, Erosion and Accretion. 1. INTRODUCTION Coastal region of the south eastern part of India is significant with respect to archaeological studies. The modest tide and wave action in the Bay of Bengal has enabled the formation and continuance of many coastal sites. -

Timeline of the Virgin Islands with Emphasis on Linguistics, Compiled by Sara Smollett, 2011

Timeline of the Virgin Islands with emphasis on linguistics, compiled by Sara Smollett, 2011. Sources: Hall, Slave Society in the Danish West Indies, 1992; Dookhan, A History of the Virgin Islands of the United States, 1994; Westergaard, The Danish West Indies under Company Rule (1671 { 1754), 1917; Oldendorp, Historie der caribischen Inseln Sanct Thomas, 1777; Highfield, The French Dialect of St Thomas, 1979; Boyer, America's Virgin Islands, 2010; de Albuquerque and McElroy in Glazier, Caribbean Ethnicity Revisited, 1985; http://en.wikipedia.org/; http://www.waterislandhistory.com; http://www.northamericanforts.com/; US census data I've used modern names throughout for consistency. However, at various previous points in time: St Croix was Santa Cruz, Christiansted was Bassin; Charlotte Amalie was Taphus; Vieques was Crab Island; St Kitts was St Christopher. Pre-Columbus .... first Ciboneys, then later Tainos and Island Caribs settle the Virgin Islands Early European exploration 1471 Portuguese arrive on the Gold Coast of Africa 1493 Columbus sails past and names the islands, likely lands at Salt River on St Croix and meets natives 1494 Spain and Portugal define the Line of Demarcation 1502 African slaves are first brought to Hispanola 1508 Ponce de Le´onsettles Puerto Rico 1553 English arrive on the Gold Coast of Africa 1585 Sir Francis Drake likely anchors at Virgin Gorda 1588 Defeat of the Spanish Armada 1593 Dutch arrive on the Gold Coast of Africa 1607 John Smith stopped at St Thomas on his way to Jamestown, Virginia Pre-Danish settlement -

Variation and Change in Virgin Islands Dutch Creole Tense, Modality and Aspect

VARIATION AND CHANGE IN VIRGIN ISLANDS DUTCH CREOLE TENSE, MODALITY AND ASPECT Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6111 Trans 10 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration: Annaberg sugar mill ruins, St. John, US Virgin Islands. Picture taken by flickr user Navin75. Original in full color. Reproduced and adapted within the freedoms granted by the license terms (CC BY-SA 2.0) applied by the licensor. ISBN: 978-94-6093-235-9 NUR 616 Copyright © 2017: Robbert van Sluijs. All rights reserved. Variation and change in Virgin Islands Dutch Creole Tense, Modality and Aspect Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. dr. J.H.J.M. van Krieken, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 11 mei 2017 om 10.30 uur precies door Robbert van Sluijs geboren op 23 januari 1987 te Heerlen Promotor: Prof. dr. P.C. Muysken Copromotor: Dr. M.C. van den Berg (UU) Manuscriptcommissie: Prof. dr. R.W.N.M. van Hout Dr. A. Bruyn (Instituut voor de Nederlandse Taal, Den Haag) Prof. dr. F.L.M.P. Hinskens (VU) Prof. dr. S. Kouwenberg (University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica) Prof. dr. C.H.M. Versteegh Part of the research reported in this dissertation was funded by the Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen (KNAW). i TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v ABBREVIATIONS ix 1. VARIATION IN VIRGIN ISLANDS DUTCH CREOLE: TENSE-ASPECT- MODALITY 1 1.1. -

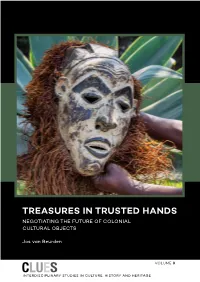

Treasures in Trusted Hands

Van Beurden Van TREASURES IN TRUSTED HANDS This pioneering study charts the one-way traffic of cultural “A monumental work of and historical objects during five centuries of European high quality.” colonialism. It presents abundant examples of disappeared Dr. Guido Gryseels colonial objects and systematises these into war booty, (Director-General of the Royal confiscations by missionaries and contestable acquisitions Museum for Central Africa in by private persons and other categories. Former colonies Tervuren) consider this as a historical injustice that has not been undone. Former colonial powers have kept most of the objects in their custody. In the 1970s the Netherlands and Belgium “This is a very com- HANDS TRUSTED IN TREASURES returned objects to their former colonies Indonesia and mendable treatise which DR Congo; but their number was considerably smaller than has painstakingly and what had been asked for. Nigeria’s requests for the return of with detachment ex- plored the emotive issue some Benin objects, confiscated by British soldiers in 1897, of the return of cultural are rejected. objects removed in colo- nial times to the me- As there is no consensus on how to deal with colonial objects, tropolis. He has looked disputes about other categories of contestable objects are at the issues from every analysed. For Nazi-looted art-works, the 1998 Washington continent with clarity Conference Principles have been widely accepted. Although and perspicuity.” non-binding, they promote fair and just solutions and help people to reclaim art works that they lost involuntarily. Prof. Folarin Shyllon (University of Ibadan) To promote solutions for colonial objects, Principles for Dealing with Colonial Cultural and Historical Objects are presented, based on the 1998 Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. -

Postcolonising Danish Foreign Policy Activism in the Global South: Cases of Ghana, India and the Us Virgin

Nikita Pliusnin POSTCOLONISING DANISH FOREIGN POLICY ACTIVISM IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH: CASES OF GHANA, INDIA AND THE US VIRGIN ISLANDS Faculty of Management and Business Master‟s Thesis April 2021 ABSTRACT Nikita Pliusnin: Postcolonising Danish Foreign Policy Activism in the Global South: Cases of Ghana, India and the US Virgin Islands Master‟s Thesis Tampere University Master‟s Programme in Leadership for Change, European and Global Politics, CBIR April 2021 There is a growing corpus of academic literature, which is aimed to analyse Danish activism as a new trend of the kingdom‟s foreign policy. Different approaches, both positivist and post-positivist ones, study specific features of activism, as well the reasons of why this kind of foreign policy has emerged in post- Cold War Denmark. Nevertheless, little has been said on the role of Danish colonial past in the formation of strategies and political courses towards other states and regions. The heterogeneous character of Danish colonialism has also been overlooked by scholars: while Greenland, Iceland and the Faroe Islands are thoroughly examined in Danish postcolonial studies, so-called „tropical colonies‟ (the Danish West Indies, the Danish Gold Coast and Danish India) are almost „forgotten‟. The aim of the thesis is to investigate how the Danish colonial past (or rather the interpretations of the past by the Danish authorities) in the Global South influences modern Danish foreign policy in Ghana, India and US Virgin Islands (the USVI) (on the present-day territories of which Danish colonies were once situated). An authored theoretical and methodological framework of the research is a compilation of discourse theory by Laclau and Mouffe (1985) and several approaches within postcolonialism, including Orientalism by Said (1978) and hybridity theory by Bhabha (1994). -

2 X 160 MW Coal Based Thermal Power Plant EXECUTIVE

PPN POWER GENERATING COMPANY PVT. LTD 2 x 160 MW Coal based Thermal Power Plant EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction PPN Power Generating Company Pvt. Ltd. (PPN) having its corporate office at Chennai, owns and operates a Combined Cycle Power Station of 330.5 MW capacity at villages of Pillaiperumalnallur and Manikkapangu of Tharangambadi Taluk of Nagapattinam District, Tamil Nadu. The existing plant is designed for 100% natural gas firing or 100% naphtha firing or a mixture of natural gas and naphtha firing ( 70 % : 30%). Presently plant is operated using 100 % naphtha due to shortage of gas from PY-01 off shore well. Since the prospects of availability of gas is remote, PPN is now planning to expand the power plant capacity from 330.5 MW to 490.5 MW by installing 2 x 160 MW coal based thermal power plant in existing plant premises. PPN has appointed Fichtner Consulting Engineers (India) Pvt. Ltd., Chennai as their Consultant/ Engineer for the preparation of Feasibility Report of the Project. This Feasibility report is prepared based on the MOEF guidelines dated 30th December 2010 for obtaining environmental clearance. The objective of this Feasibility Report is to establish the technical and commercial feasibility of the project giving details such as the site features, basic plant configuration, salient technical features and financial parameters of the proposed 2 x 160 MW Thermal Power Plant. Project Description The proposed power project will be located adjacent to the existing combined cycle power plant location. The proposed site is located in Pillaiperumalnallur and Manikkapangu villages near Thirukkadaiyur in Tharangambadi Taluka of Nagapatinam District, Tamil Nadu. -

LIST of FARMS REGISTERED in NAGAPATTINAM DISTRICT * Valid for 5 Years from the Date of Issue

LIST OF FARMS REGISTERED IN NAGAPATTINAM DISTRICT * Valid for 5 Years from the Date of Issue. Address Farm Address S.No. Registration No. Name Father's / Husband's name Survey Number Issue date * Village / P.O. Mandal District Mandal Revenue Village 461/4-5-7; 461/8A, Nagapattinam 8B,9,10,11A,11 1 TN-II-2007(0071) N Sakkaravarthi Shri Nagappan Palayagaram Vanagiri village Sirkali Taluk District Sirkali Vanagiri B 23.08.2007 M/s Jayaram South Street, Nagapattinam Thandavanku 17/1, 17/2A1, 2 TN-II-2007(0072) A Kathirvel Shri Andiyappan Aqua Farm Koozaiyar & PO, Sirkali Taluk District Sirkali lam 17/2A2 23.08.2007 Nagapattinam 3 TN-II-2007(0073) E Chandran Shri P Emperumal Fishermen Street Vanagiri & PO, Sirkali Taluk District Sirkali 83 Keelaiyur 443/4,5 23.08.2007 M/s 39 - Navaneethakann Sithivinayagapura Nagapattinam Thandavanku 17/2B, 29/1B, 4 TN-II-2007(0074) T Kannan Shri Thiruvengadam an Aqua Farm m, Sirkali Taluk District Sirkali lam 29/9 23.08.2007 Madavamedu, Pudupattinam Nagapattinam 5 TN-II-2007(0075) V Vembu Shri Veeramani PO Madavamedu Sirkali Taluk District Sirkali Madavamedu 332-3 23.08.2007 452/8A-8B-7B- 8D-8H-11B; 8G- Poompuhar PO - Nagapattinam 10B; 8F - 10A - 6 TN-II-2007(0076) S Gnanasekaran Shri Sinnathambi V Main Road, 609 105 Sirkali Taluk District Sirkali Vanagiri 9B - 7C -8E 23.08.2007 Nagapattinam 7 TN-II-2007(0077) T Anjali Shri A Thangaraj Madavamedu Pudhupattinam, Sirkali Taluk District Sirkali Madavamedu 332/3 23.08.2007 No.1/15, Vellalar Melaperumpallam, Nagapattinam 8 TN-II-2007(0078) S Vanangamudi Shri S -

EMAMI LIMITED Unclaimed Dividend for the Year 2007-08 As on 09.08.2014

EMAMI LIMITED Unclaimed dividend for the year 2007-08 as on 09.08.2014 SR.NO Name Address Folio Number of Securities Amount Due(in Rs.) 1 A B GHOSH 69 ANANDA PALIT ROAD,KOLKATA A00104 4.50 2 A PAL C/O PANKAJ KR DAS,VILL NUTANGRAM P.O.MOGRA,DT HOOGHLY,- A00105 4.50 3 ACHINTYA KUMAR SANTRA G N MUKHERJEE ROAD,P.O.BANSBERIA,DIST HOOGHLY,- A00116 4.50 4 ALOK KRISHNA DS 8 DINDLI ENCLAVE,PUNSA ROAD,P O KADMA,JAMSHEDPUR IN30045010316575 90.00 5 ALPANA GHOSH 69 ANANDA PALIT ROAD,KOLKATA,-,- A00103 4.50 6 AMIT NARAYAN BISWAS C/O SABITRI HAZARE,MADHUSUDAN NAGAR,TULASIPUR,CUTTACK IN30154918909006 450.00 7 ANA MARIA AFONSO HOUSE NO.145,,CAMPAL,PANJI,GOA INDIA 1203830000002008 450.00 8 ANAND DHUNDIRAJ JOG `RAJAS`,PLOT NO 42 , NAMRAJ CO-OP HSG SOC,KARVE NAGAR,PUNE IN30028010208741 3375.00 9 ANIL KUMAR SINGH A 214 NANDGIRI ASHIANA ENCLAVE,DIMNA ROAD,MANGO,JAMSHEDPUR IN30267935554506 4.50 10 ANIL SIDRAM SHRIRAM 30/87 B PADMA NAGAR,NEW PACCHA PETH,-,SOLAPUR IN30109810273003 450.00 11 ANILA BIPINCHANDRA PAREKH PARAS,,33-A, SHRIRAM PARK, STREET NO. 1,,KALAVAD ROAD,,RAJKOT. IN30097410571852 22.50 12 ANSUYABEN MAGANLAL VASOYA SAHID ARJUN ROAD,NR,NEW LEUA PATEL SAMAJ,UPLETA,GUJARAT INDIA 1301990000135337 450.00 13 ANURAG PRASAD ASHIANA HIG,,A-211,,MORADABAD,,UTTAR PRADESH IN30226910879774 225.00 14 AREPALLY LAKSHMIKANTHA REDDY W 1A-55,WILLENGTON ESTATE,DLF PHASE-V,GURGAON IN30290240840509 450.00 15 ARUNA LAL GI 5,SHIRINE GARDEN OPP ITI,AUNDH,PUNE IN30267936374263 450.00 16 ASHA DEVI SECTOR 2B,QR NO 2/102 BOKARO STEEL CITY,BOKARO,JHARKHAND INDIA 1202300000260707