The Continuities of Convict-Leasing and an Analysis of Arkansas Prison Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Cattle: Prison Overpopulation and the Political Economy of Mass Incarceration

Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science Volume 4 Article 3 5-10-2016 Human Cattle: Prison Overpopulation and the Political Economy of Mass Incarceration Peter Hanna San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/themis Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Hanna, Peter (2016) "Human Cattle: Prison Overpopulation and the Political Economy of Mass Incarceration," Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science: Vol. 4 , Article 3. https://doi.org/10.31979/THEMIS.2016.0403 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/themis/vol4/iss1/3 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Justice Studies at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Themis: Research Journal of Justice Studies and Forensic Science by an authorized editor of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Human Cattle: Prison Overpopulation and the Political Economy of Mass Incarceration Abstract This paper examines the costs and impacts of prison overpopulation and mass incarceration on individuals, families, communities, and society as a whole. We start with an overview of the American prison system and the costs of maintaining it today, and move on to an account of the historical background of the prison system to provide context for the discussions later in this paper. This paper proceeds to go into more detail about the financial and social costs of mass incarceration, concluding that the costs of the prison system outweigh its benefits. This paper will then discuss the stigma and stereotypes associated with prison inmates that are formed and spread through mass media. -

Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2015 Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice Allegra M. McLeod Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1490 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2625217 62 UCLA L. Rev. 1156-1239 (2015) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice Allegra M. McLeod EVIEW R ABSTRACT This Article introduces to legal scholarship the first sustained discussion of prison LA LAW LA LAW C abolition and what I will call a “prison abolitionist ethic.” Prisons and punitive policing U produce tremendous brutality, violence, racial stratification, ideological rigidity, despair, and waste. Meanwhile, incarceration and prison-backed policing neither redress nor repair the very sorts of harms they are supposed to address—interpersonal violence, addiction, mental illness, and sexual abuse, among others. Yet despite persistent and increasing recognition of the deep problems that attend U.S. incarceration and prison- backed policing, criminal law scholarship has largely failed to consider how the goals of criminal law—principally deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, and retributive justice—might be pursued by means entirely apart from criminal law enforcement. Abandoning prison-backed punishment and punitive policing remains generally unfathomable. This Article argues that the general reluctance to engage seriously an abolitionist framework represents a failure of moral, legal, and political imagination. -

Prisoner Testimonies of Torture in United States Prisons and Jails

Survivors Speak Prisoner Testimonies of Torture in United States Prisons and Jails A Shadow Report Submitted for the November 2014 Review of the United States by the Committee Against Torture I. Reporting organization The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) is a Quaker faith based organization that promotes lasting peace with justice, as a practical expression of faith in action. AFSC’s interest in prison reform is strongly influenced by Quaker (Religious Society of Friends) activism addressing prison conditions as informed by the imprisonment of Friends for their beliefs and actions in the 17th and 18th centuries. For over three decades AFSC has spoken out on behalf of prisoners, whose voices are all too frequently silenced. We have received thousands of calls and letters of testimony of an increasingly disturbing nature from prisoners and their families about conditions in prison that fail to honor the Light in each of us. Drawing on continuing spiritual insights and working with people of many backgrounds, we nurture the seeds of change and respect for human life that transform social relations and systems. AFSC works to end mass incarceration, improve conditions for people who are in prison, stop prison privatization, and promote a reconciliation and healing approach to criminal justice issues. Contact Person: Lia Lindsey, Esq. 1822 R St NW; Washington, DC 20009; USA Email: [email protected] +1-202-483-3341 x108 Website: www.afsc.org Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible but for the courageous individuals held in U.S. prisons and jails who rise above the specter of reprisal for sharing testimonies of the abuses they endure. -

Twin Cities Public Television, Slavery by Another Name

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Public Programs application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/public/americas-media-makers-production-grants for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Public Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Slavery By Another Name Institution: Twin Cities Public Television, Inc. Project Director: Catherine Allan Grant Program: America’s Media Makers: Production Grants 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 426, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8269 F 202.606.8557 E [email protected] www.neh.gov SLAVERY BY ANOTHER NAME NARRATIVE A. PROGRAM DESCRIPTION Twin Cities Public Television requests a production grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) for a multi-platform initiative entitled Slavery by Another Name based upon the 2008 Pulitzer Prize-winning book written by Wall Street Journal reporter Douglas Blackmon. Slavery by Another Name recounts how in the years following the Civil War, insidious new forms of forced labor emerged in the American South, keeping hundreds of thousands of African Americans in bondage, trapping them in a brutal system that would persist until the onset of World War II. -

Slavery by Another Name History Background

Slavery by Another Name History Background By Nancy O’Brien Wagner, Bluestem Heritage Group Introduction For more than seventy-five years after the Emancipation Proclamation and the end of the Civil War, thousands of blacks were systematically forced to work against their will. While the methods of forced labor took on many forms over those eight decades — peonage, sharecropping, convict leasing, and chain gangs — the end result was a system that deprived thousands of citizens of their happiness, health, and liberty, and sometimes even their lives. Though forced labor occurred across the nation, its greatest concentration was in the South, and its victims were disproportionately black and poor. Ostensibly developed in response to penal, economic, or labor problems, forced labor was tightly bound to political, cultural, and social systems of racial oppression. Setting the Stage: The South after the Civil War After the Civil War, the South’s economy, infrastructure, politics, and society were left completely destroyed. Years of warfare had crippled the South’s economy, and the abolishment of slavery completely destroyed what was left. The South’s currency was worthless and its financial system was in ruins. For employers, workers, and merchants, this created many complex problems. With the abolishment of slavery, much of Southern planters’ wealth had disappeared. Accustomed to the unpaid labor of slaves, they were now faced with the need to pay their workers — but there was little cash available. In this environment, intricate systems of forced labor, which guaranteed cheap labor and ensured white control of that labor, flourished. For a brief period after the conclusion of fighting in the spring of 1865, Southern whites maintained control of the political system. -

Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : a Finding Aid

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids and Research Guides for Finding Aids: All Items Manuscript and Special Collections 5-1-1994 Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives. James Anthony Schnur Hugh W. Cunningham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all Part of the Archival Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives.; Schnur, James Anthony; and Cunningham, Hugh W., "Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid" (1994). Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items. 19. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all/19 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids and Research Guides for Manuscript and Special Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection A Finding Aid by Jim Schnur May 1994 Special Collections Nelson Poynter Memorial Library University of South Florida St. Petersburg 1. Introduction and Provenance In December 1993, Dr. Hugh W. Cunningham, a former professor of journalism at the University of Florida, donated two distinct newspaper collections to the Special Collections room of the USF St. Petersburg library. The bulk of the newspapers document events following the November 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy. A second component of the newspapers examine the reaction to Richard M. Nixon's resignation in August 1974. -

Riverside Vocational Technical School

DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS - RIVERSIDE VOCATIONAL TECHNICAL SCHOOL State Contracts Over $50,000 Awarded To Minority Owned Businesses Fiscal Year 2020 None Employment Summary Male Female Total % White Employees 17 10 27 93 % Black Employees 1 1 2 7 % Other Racial Minorities 0 0 0 0 % Total Minorities 2 7 % Total Employees 29 100 % Publications A.C.A. 25-1-201 et seq. Required for Unbound Black & Cost of Unbound Statutory # of Reason(s) for Continued White Copies Copies Produced Name General Authorization Governor Copies Publication and Distribution Produced During During the Last Assembly the Last Two Years Two Years N/A N/A N N 0 N/A 0 0.00 DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS - RIVERSIDE VOCATIONAL TECHNICAL SCHOOL - 0582 Page 338 Solomon Graves, Secretary DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS - RIVERSIDE VOCATIONAL TECHNICAL SCHOOL - 0582 Solomon Graves, Secretary Department Appropriation Summary Historical Data Agency Request and Executive Recommendation 2019-2020 2020-2021 2020-2021 2021-2022 2022-2023 Appropriation Actual Pos Budget Pos Authorized Pos Agency Pos Executive Pos Agency Pos Executive Pos 732 Riverside VT-State Operations 2,043,561 32 2,201,017 33 2,384,278 35 2,447,268 35 2,447,268 35 2,451,964 35 2,451,964 35 750 Plumbing Apprenticeship Program 66,486 1 54,609 1 79,032 1 79,032 1 79,032 1 79,032 1 79,032 1 Total 2,110,047 33 2,255,626 34 2,463,310 36 2,526,300 36 2,526,300 36 2,530,996 36 2,530,996 36 Funding Sources % % % % % % General Revenue 4000010 2,110,047 100.0 2,255,626 100.0 2,430,701 100.0 2,312,769 100.0 2,435,018 100.0 2,317,086 -

Spring 2012 a Publication of the CPO Foundation Vol

CPO FAMILY Spring 2012 A Publication of The CPO Foundation Vol. 22, No. 1 The Correctional Peace Officers Foundation CPO Family The Correctional Peace Officers’ Foundation was founded in the early 1980s at Folsom State Prison in California. If this is the first time you are reading one of our semi-annual publications, the magazine, welcome! And to all those that became Supporting Members in the middle to late 1980s and all the years that have followed, THANKS for making the Correctional Peace Officers’ (CPO) Foundation the organization it is today. The CPO Foundationbe there immediatelywas created with two goals Correctional Officer Buddy Herron in mind: first, to Eastern Oregon Correctional Institution in the event of EOW: November 29, 2011 a line-of-duty death; and second, to promote a posi- tive image of the Correc- tions profession. Correctional Officer Tracy Hardin We ended 2011 tragi- High Desert State Prison, Nevada cally with the murder of C/O Buddy Herron of East- EOW: January 20, 2012 ern Oregon Correctional Institution in Pendleton, Oregon. Upon hearing of his death I immediately Correctional Corporal Barbara Ester flew to Portland, Oregon, East Arkansas Unit along with Kim Blakley, EOW: January 20, 2012 and met up with Oregon CPOF Field Representative Dan Weber. Through the Internet the death of one of our own spreads quickly. Correctional Sergeant Ruben Thomas III As mentioned in the Com- Columbia Correctional Institution, Florida mander’s article (inside, EOW: March 18, 2012 starting on page 10), Honor Guards from across the na- tion snapped to attention. Corrections Officer Britney Muex Thus, Kim and I were met in Pendleton by hundreds and Lake County Sheriff’s Department, Indiana hundreds of uniform staff. -

Men, Women and Children in the Stockade: How the People, the Press, and the Elected Officials of Florida Built a Prison System Anne Haw Holt

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Men, Women and Children in the Stockade: How the People, the Press, and the Elected Officials of Florida Built a Prison System Anne Haw Holt Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Men, Women and Children in the Stockade: How the People, the Press, and the Elected Officials of Florida Built a Prison System by Anne Haw Holt A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2005 Copyright © 2005 Anne Haw Holt All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Anne Haw Holt defended September 20, 2005. ________________________________ Neil Betten Professor Directing Dissertation ________________________________ David Gussak Outside Committee Member _________________________________ Maxine Jones Committee Member _________________________________ Jonathon Grant Committee Member The office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members ii To my children, Steve, Dale, Eric and Jamie, and my husband and sweetheart, Robert J. Webb iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe a million thanks to librarians—mostly the men and women who work so patiently, cheerfully and endlessly for the students in the Strozier Library at Florida State University. Other librarians offered me unstinting help and support in the State Library of Florida, the Florida Archives, the P. K. Yonge Library at the University of Florida and several other area libraries. I also thank Dr. -

Annual Report

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. .. " ANNUAL REPORT, I I /, i • . .. Information contained in this report was collected from staff, compiled, and analyzed by the Research, Planning, and Management Services Division. Typography by Graphic Arts-Women'g Unit Arkansas Correctional Industries Printing by Duplicating Services-Wrightsville Unit Arkansas Correctional Industries /(J75JI ARKANSAS DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTION POST OFFICE BOX 8707 PINE BLUFF, ARKANSAS 71611 0 PHONE: (501) 247-1800 A. L. LOCKHART, Director BILL CLINTON WOODSON D. WALKER Governor Chairman Boord of Correction June 30, 1986 The Honorable Bill Clinton Governor, State of Arkansas State Capitol Building Little Rock, AR 72201 Dear Governor Clinton: In accordance with Act 50, Section 5, paragraph (f) of the Arkansas Statutes, the Department of Correction respectfully submits its Annual Report for the fiscal year 1985·86. This report will provide you, the General Assembly, and other interested individuals and agencies, with information regarding the activities, function, quantitative analysis and impact of the Arkansas Department of Correction as it executes its statutory responsibility for the custody, care, treatment and management of adult offenders. The goal of the Department is to provide for the protection of free society by carrying out the mandate of the courts; provide a safe and humane environment for staff and inmates; strengthen the work ethic through the teaching of good work habits; and provide opportunities for inmates .0 improve spiritually, mentally and physically. The employees of the Department of Correction are committed to improving all programs and maintaining a constitutional status with prior federal court orders. -

BOARD REPORT January 2021

BOARD REPORT January 2021 FARM During the month of December, steers from both farms were RESEARCH/PLANNING sold through Superior Livestock at a good price and were shipped out prior to Christmas. All heifers are being held as possible December 2020 Admissions and Releases – Admissions for replacements for the coming year. December 2020 totaled 468 (402-males and 66-females) while releases totaled 522 (449-males and 73 females) for a net decrease Greenhouses are being finished out at units across the state in in-house of 54 inmates. preparation of being operational by spring. Inmate Population Growth/Projection – At the end of December Thirty head of dairy cattle were purchased from an Arkansas 2020, the jurisdictional population for the Division of Correction dairy. A total of 15 are fresh milking and the remaining half are totaled 16,094, representing a decrease of 1,665 inmates since the springing heifers. This purchase has already increased the milk first of January 2020. Calendar year 2020 has seen an average decrease production for Farm Operations. of 139 inmates per month, which is up from an average monthly In anticipation of planting the 2021 crops, row crop crews decrease of three inmates per month during calendar year 2019. worked in the shops preparing equipment. Average County Jail Back-up – The backup in the county jails averaged 1,853 inmates per day during the month of December REGIONAL MAINTENANCE HOURS 2020, which was down from the per-day average of 1,986 inmates Regional Maintenance Hours December 2020 during the month of November 2020. -

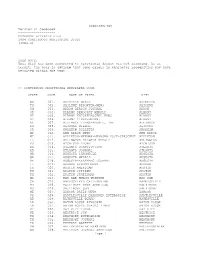

Appendix File 1984 Continuous Monitoring Study (1984.S)

appcontm.txt Version 01 Codebook ------------------- CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE 1984 CONTINUOUS MONITORING STUDY (1984.S) USER NOTE: This file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As as result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. >> CONTINUOUS MONITORING NEWSPAPER CODE STATE CODE NAME OF PAPER CITY WA 001. ABERDEEN WORLD ABERDEEN TX 002. ABILENE REPORTER-NEWS ABILENE OH 003. AKRON BEACON JOURNAL AKRON OR 004. ALBANY DEMOCRAT-HERALD ALBANY NY 005. ALBANY KNICKERBOCKER NEWS ALBANY NY 006. ALBANY TIMES-UNION, ALBANY NE 007. ALLIANCE TIMES-HERALD, THE ALLIANCE PA 008. ALTOONA MIRROR ALTOONA CA 009. ANAHEIM BULLETIN ANAHEIM MI 010. ANN ARBOR NEWS ANN ARBOR WI 011. APPLETON-NEENAH-MENASHA POST-CRESCENT APPLETON IL 012. ARLINGTON HEIGHTS HERALD ARLINGTON KS 013. ATCHISON GLOBE ATCHISON GA 014. ATLANTA CONSTITUTION ATLANTA GA 015. ATLANTA JOURNAL ATLANTA GA 016. AUGUSTA CHRONICLE AUGUSTA GA 017. AUGUSTA HERALD AUGUSTA ME 018. AUGUSTA-KENNEBEC JOURNAL AUGUSTA IL 019. AURORA BEACON NEWS AURORA TX 020. AUSTIN AMERICAN AUSTIN TX 021. AUSTIN CITIZEN AUSTIN TX 022. AUSTIN STATESMAN AUSTIN MI 023. BAD AXE HURON TRIBUNE BAD AXE CA 024. BAKERSFIELD CALIFORNIAN BAKERSFIELD MD 025. BALTIMORE NEWS AMERICAN BALTIMORE MD 026. BALTIMORE SUN BALTIMORE ME 027. BANGOR DAILY NEWS BANGOR OK 028. BARTLESVILLE EXAMINER-ENTERPRISE BARTLESVILLE AR 029. BATESVILLE GUARD BATESVILLE LA 030. BATON ROUGE ADVOCATE BATON ROUGE LA 031. BATON ROUGE STATES TIMES BATON ROUGE MI 032. BAY CITY TIMES BAY CITY NE 033. BEATRICE SUN BEATRICE TX 034. BEAUMONT ENTERPRISE BEAUMONT TX 035. BEAUMONT JOURNAL BEAUMONT PA 036.