Financial Darwinism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEAR CONGRESS & Presldent OBAMA

STEPHEN A. ROSS, Professor of financial economics, massachusetts institute of technology • KENT SMETTERS, Professor of economics, the university of Pennsylvania • JAGADEESH GOKHALE, senior fellow, cato institute • DarON ACEMOGLU, Professor of economics, massachusetts institute of technology • JOHN MAULDIN, President, millenium wave advisors • EDWARD LEAMER, Professor of economics, university of california, los angeles • IVAN WERNING, Professor of economics, massachusetts institute of technology • DIRK KRUEGER, Professor of economics, university of Pennsylvania • JERRY HAUSMAN, Professor of economics, massachusetts institute of technology • ARNOLD C HARBERGER, distinguished Professor, university of california, los angeles • EUGENE STEUERLE, senior fellow, the urban institute • MICHAEL MANOVE, Professor of economics, boston university • TODD IDSON, associate Professor of economics, boston university • CHRISTOPHE CHAMLEY, Professor of economics, boston university • JIANJUN MIAO, associate Professor of economics, boston university • CAROLINE HOXBY, Professor of economics, stanford university • DILIP MOOKHERJEE, Professor of economics, boston university • FRANCESCO DECAROLIS, assistant Professor, boston university • PETER KARL KRESL, PROFESSOR OF ECONOMICS EMERITUS, bucknell university • RICHARD HOFLER, Professor of economics, university of central florida • ROGER FELDMAN, blue cross Professor of health insurance, university of minnesota • JERE R. BEHRMAN, Professor of economics, university of Pennsylvania • BOB CHIRINKO, Professor of finance, -

Volume 35, Number 2, June

506 Rapport d’expert de Darrell Duffi e SYSTEMIC RISK IN FINANCIAL SYSTEMS AND CAPITAL MARKETS IN RELATIONSHIP WITH THE PROPOSED DRAFT CAPITAL MARKETS STABILITY ACT Report of Darrell Duffie, Dean Witter Distinguished Professor of Finance at the Graduate School of Business, Stanford University May 3, 2016 507 Rapport d’expert de Darrell Duffi e Résumé Le présent rapport examine certaines questions relatives à l’ébauche d’avant-projet de la Loi sur la stabilité des marchés des capitaux (LSMC). Les enjeux liés à la LSMC ne sont pas étudiés de façon exhaustive dans ce rapport. Il s’agit d’un rapport parmi plusieurs rapports d’experts, chacun traitant d’un sous-ensemble de questions. La partie 1 décrit le rôle du système financier au sein de l’économie nationale en général, en mettant l’accent sur le rôle des marchés de capitaux et les interdépendances au sein des marchés de capitaux. Le système financier (c.-à-d. la partie de l’économie qui gère les flux de capitaux, la liquidité et le risque financier) est essentiel à l’économie réelle (c.-à-d. la production, la distribution et la consommation de biens réels). Sans un accès stable et peu coûteux aux marchés financiers, l’économie réelle ne pourrait fonctionner. Les marchés de capitaux sont la sous-catégorie du système financier qui comprend les marchés des réclamations relatives aux obligations et aux capitaux propres, ainsi que les services financiers et les marchés qui les soutiennent. Les produits financiers, les fournisseurs de services financiers et les marchés au sein desquels les produits financiers sont échangés sont interreliés de façon complexe et forment le système financier. -

Curriculum Vitae of DARRELL DUFFIE Contact: Email: [email protected] Personal Webpage: Darrellduffie.Com Postal Address: Gradu

Curriculum Vitae of DARRELL DUFFIE Contact: Postal Address: email: duffi[email protected] Graduate School of Business personal webpage: darrellduffie.com 655 Knight Way Stanford University Stanford CA 94305-7298 University Stanford University, Ph. D. (Engineering Economic Systems) (1984) Education University of New England (Australia), Master of Economics (Economic Statistics) (1980) University of New Brunswick (Canada), Bachelors of Science in Engineer- ing (Civil Engineering) (1975) Awards 1985-86 NSF Research Fellowship and 1988-89 Batterymarch Fellowship Honors 1990-92 NSF Research Grant 1992-93 Catalyst Institute Research Grant 1994-95 Q Group Research Award 1994-96 NSF Research Grant Fellow, Econometric Society 1997 Smith-Breeden Distinguished Paper Prize, Journal of Finance 2001 Graham and Dodd Award, Financial Analysts Journal 2002 NYSE Prize for equity research, Western Finance Association 2003 Distinguished teacher award, Doctoral Program, Graduate School of Business, Stanford University 2003 Financial Engineer of the Year, International Association of Financial Engineering 2004 Clarendon Lectures in Finance, Oxford University. 2007 Princeton Lectures in Finance. 2007 Elected Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 2008 2011, Elected to the Council of the Econometric Society. 2008 Nash Lecture, Carnegie-Mellon University. 2009 Elected President of the American Finance Association. 2010 Tinbergen Institute Finance Lectures, Duisenberg Institute. 2011 Minerva Foundation Lectures, Columbia University. 2015 Ross Prize, FARFE (with Jun Pan and Ken Singleton). 2015 Fisher-Shultz Lecture, World Congress, Econometric Society. Employment 1984-present: Graduate School of Business, Stanford University Current Position: Dean Witter Distinguished Professor of Finance On leave: Mathematical Sciences Research Institute, University of Califor- nia, Berkeley, 1985-1986; Universit´ede Paris, Dauphine, 1998; University of Lausanne, 2007-2008; EPFL, 2015-2016. -

Booklist 2008 Rev

Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik; Terrorismus 1 Wirtschafts- und Finanzkrise 26 Klima- und Energiepolitik 35 Wahlkampf, Bios, Politik und Religion, Zukunft GOP 41 Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik; Terrorismus “America and the World: Conversations on the Future of American For- eign Policy” Zbigniew Brzezinski, Brent Scowcroft, David Ignatius Publisher: Perseus Publishing Pub. Date: September 2008 Hardcover 304pp Synopsis The two most respected figures in American foreign policy define the international challenges facing the next president in the must-read foreign policy book of the season. Given the bitterness of partisan debates about foreign policy, now exacerbated by a tight race for the presidency, one might expect Brzezinski and Scowcroft to disagree vehemently about the challenges America faces abroad, the deci- sions that have shaped the nation's current travails and what the next president should do. Instead, they seem to see eye to eye on nearly every major foreign policy issue facing the United States…And, contrary to the operative assumption behind Sunday morning TV talk shows, it turns out that two wise interlocutors who concur can be as interesting and informative as experts with completely divergent views…The next president would do well to heed their counsel but should not underestimate the diffi- culty of sticking to it. “Strongest Tribe: War, Politics, and the Endgame in Iraq” Bing West Publisher: Random House Adult Trade Publishing Group Pub. Date: August 2008 Hardcover 464pp Synopsis From a universally respected combat journalist, a gripping history based on five years of front-line reporting about how the war was turned around–and the choice now facing America. -

Curriculum Vitae of DARRELL DUFFIE Contact: Email: Duffie

Curriculum Vitae of DARRELL DUFFIE Contact: Postal Address: email: duffi[email protected] Graduate School of Business personal webpage: darrellduffie.com 655 Knight Way Stanford University Stanford CA 94305-7298 University Stanford University, Ph. D. (Engineering Economic Systems) (1984) Education University of New England (Australia), Master of Economics (Economic Statistics) (1980) University of New Brunswick (Canada), Bachelors of Science in Engineer- ing (Civil Engineering) (1975) Awards 1985-86 NSF Research Fellowship and 1988-89 Batterymarch Fellowship Honors 1990-92 NSF Research Grant 1992-93 Catalyst Institute Research Grant 1994-95 Q Group Research Award 1994-96 NSF Research Grant Fellow, Econometric Society 1997 Smith-Breeden Distinguished Paper Prize, Journal of Finance 2001 Graham and Dodd Award, Financial Analysts Journal 2002 NYSE Prize for equity research, Western Finance Association 2003 Distinguished teacher award, Doctoral Program, Graduate School of Business, Stanford University 2003 Financial Engineer of the Year, International Association of Financial Engineering 2004 Clarendon Lectures in Finance, Oxford University. 2007 Princeton Lectures in Finance. 2007 Elected Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 2008 2011, Elected to the Council of the Econometric Society. 2008 Nash Lecture, Carnegie-Mellon University. 2009 Elected President of the American Finance Association. 2010 Tinbergen Institute Finance Lectures, Duisenberg Institute. 2011 Minerva Foundation Lectures, Columbia University. 2015 Ross Prize, FARFE (with Jun Pan and Ken Singleton). 2015 Fisher-Shultz Lecture, World Congress, Econometric Society. 2016 AQR Prize (with Haoxiang Zhu). 2017 Baffi Lecture, Banca d'Italia. 2018 Amundi Smith Breeden Prize, best paper, Journal of Finance. 2021 Bies Lecture, Northwestern University. Employment 1984-present: Graduate School of Business, Stanford University, professor by courtesy, Department of Economics, Stanford University. -

Career Development Resources

IEOR Faculty Profiles Resume Portfolio 2007-2008 Guillermo Gallego Professor Department Chairman [email protected] Professor Guillermo Gallego joined Columbia University's Industrial Engineering and Operations Research Department in 1988 where he has been conducting research in the areas of Inventory Theory, Supply Chain Management, Revenue Management and semi-conductor manufacturing. His work has been supported by numerous Industrial and Government grants. Professor Gallego has published influential papers in the leading journals of his field where he has also occupied a variety of editorial positions. Professor Gallego has consulted for large corporations such as IBM, Lucent, and Northwest Airlines, and government agencies such as the National Research Council and the National Science Foundation. His graduate students are associated with prestigious universities. He spent his 1996-97 sabbatical at Stanford University and was a visiting scientist at the IBM Watson Research Center from 1999-2003. He was elected Chairman of the IEOR Department in July of 2002. Alan Beilis Adjunct Associate Professor Banc of America Securities [email protected] Dr. Beilis received his Ph.D. from New York University, in the area of acoustic wave propagation. He joined Bell Laboratories, engaging in applied research and development in the areas of acoustic wave propagation, government communications and nuclear weapons effects on communication systems. In 1986, he went to Wall Street. His work has been in the areas of model development (specifically, MBS pricing and prepayment modeling, generally, fixed income securities, equity derivatives, interest rate modeling), model validation and market risk management. As an Adjunct Professor, Dr. Beilis has taught courses in Futures and Options, both at Fordham University and in the Langone Program at New York University. -

Advanced Bond Portfolio Management

ffirst.frm Page iii Monday, November 21, 2005 1:15 PM Advanced Bond Portfolio Management Best Practices in Modeling and Strategies FRANK J. FABOZZI LIONEL MARTELLINI PHILIPPE PRIAULET EDITORS John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirst.frm Page iv Monday, November 21, 2005 1:15 PM Copyright © 2006 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or oth- erwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rose- wood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Per- missions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. -

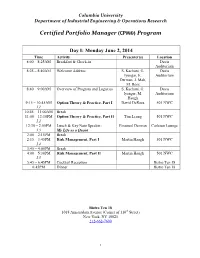

Certified Portfolio Manager (CPM®) Program

Columbia University Department of Industrial Engineering & Operations Research Certified Portfolio Manager (CPM®) Program Day I: Monday June 2, 2014 Time Activity Presenter(s) Location 8:00 – 8:25AM Breakfast & Check-in Davis Auditorium 8:25 – 8:40AM Welcome Address S. Kachani, G. Davis Iyengar, E. Auditorium Derman, J. Mak, M. Ross 8:40 – 9:00AM Overview of Program and Logistics S. Kachani, G. Davis Iyengar, M. Auditorium Haugh 9:15 – 10:45AM Option Theory & Practice, Part I David DeRosa 501 NWC I.1 10:45 – 11:00AM Break 11:00 – 12:30PM Option Theory & Practice, Part II Tim Leung 501 NWC I.2 12:30 – 2:00PM Lunch & Key Note Speaker: Emanuel Derman Carleton Lounge I.3 My Life as a Quant 2:00 – 2:15PM Break 2:15 – 3:45PM Risk Management, Part I Martin Haugh 501 NWC I.4 3:45 – 4:00PM Break 4:00 – 5:30PM Risk Management, Part II Martin Haugh 501 NWC I.5 5:45 – 6:45PM Cocktail Reception Bistro Ten 18 6:45PM Dinner Bistro Ten 18 Bistro Ten 18 1018 Amsterdam Avenue (Corner of 110th Street) New York, NY 10025 212-662-7600 1 Columbia University Department of Industrial Engineering & Operations Research Certified Portfolio Manager (CPM®) Program Day II: Tuesday June 3, 2014 Time Activity Presenter(s) Location 8:30 – 9:05AM Breakfast & Check-in Carleton Lounge 9:15 – 10:45AM Asset Allocation, Part I Garud Iyengar 501 NWC II.1 10:45 – 11:00AM Break 11:00 – 12:30PM Asset Allocation, Part II Garud Iyengar 501 NWC II.2 12:30 – 2:00PM Lunch & Key Note Speaker: James Grant Carleton Lounge II.3 Bringing back the Gold Standard 2:00 – 2:15PM Break 2:15 – 3:45PM. -

Career Development Resources

IEOR Faculty Profiles @ 2007 IEOR Orientation Program Guillermo Gallego Professor Department Chairman [email protected] Professor Guillermo Gallego joined Columbia University's Industrial Engineering and Operations Research Department in 1988 where he has been conducting research in the areas of Inventory Theory, Supply Chain Management, Revenue Management and semi-conductor manufacturing. His work has been supported by numerous Industrial and Government grants. Professor Gallego has published influential papers in the leading journals of his field where he has also occupied a variety of editorial positions. Professor Gallego has consulted for large corporations such as IBM, Lucent, and Northwest Airlines, and government agencies such as the National Research Council and the National Science Foundation. His graduate students are associated with prestigious universities. He spent his 1996-97 sabbatical at Stanford University and was a visiting scientist at the IBM Watson Research Center from 1999-2003. He was elected Chairman of the IEOR Department in July of 2002. Alan Beilis Adjunct Associate Professor Banc of America Securities [email protected] Dr. Beilis received his Ph.D. from New York University, in the area of acoustic wave propagation. He joined Bell Laboratories, engaging in applied research and development in the areas of acoustic wave propagation, government communications and nuclear weapons effects on communication systems. In 1986, he went to Wall Street. His work has been in the areas of model development (specifically, MBS pricing and prepayment modeling, generally, fixed income securities, equity derivatives, interest rate modeling), model validation and market risk management. As an Adjunct Professor, Dr. Beilis has taught courses in Futures and Options, both at Fordham University and in the Langone Program at New York University. -

Risk Management View of Global Best Practices in ERM for Insurers and Financial Supervision Reinsurers Webcast by Stephen W

R ISK M ANAGEMENT S ECTION “A JOINT SECTION OF SOCIETY OF ACTUARIES, CASUALTY ACTUARIAL SOCIETY AND CANADIAN INSTITUTE OF ACTUARIES” August 2008, Issue No. 13 Risk Published in Schaumburg, Ill. Management by the Society of Actuaries Table of Contents Diversity is the Spice of Life International Survey of Emerging Risks by Ronald J. Harasym ____________________ 2 by Max J. Rudolph _____________________ 33 ERM Perspectives Summary of “Variance of the CTE Estimator” by Wayne H. Fisher ______________________ 4 by John Manistre and Geoffrey Hancock _____ 37 An Enterprise Risk Management View of Global Best Practices in ERM for Insurers and Financial Supervision Reinsurers Webcast by Stephen W. Hiemstra __________________ 9 by Tsana Nobles _______________________ 43 Increasing the usefulness of ERM to ERM Symposium: Notes on a Conference insurance companies by Stephen W. Hiemstra and Valentina Isakina 50 Jean-Pierre Berliet ______________________ 18 Third Year a Charm for ERM Symposium Risk Identification: A Critical First Step in Scientific Papers Track Enterprise Risk Management by Steven C. Siegel _____________________ 55 by Sim Segal __________________________ 29 Risk Management w August 2008 Chairman’sChairperson’s Corner Corner Diversity is the Spice of Life! Ronald J. Harasym fabulous thing about Looking at some of the articles in this issue enterprise risk man- of the newsletter, there is a wide and exciting A agement (ERM) is range of topics. Wayne Fisher discusses what it the diversity of issues that takes to successfully embed ERM in a firm, the one can become involved in. development of models and setting parameters, Timing is everything! There and the importance of research. -

IEOR Faculty Profiles 2011-2012

IEOR Faculty Profiles 2011-2012 Daniel Bienstock Professor Director of Doctoral Programs, IEOR Director of Computational Optimization Research Center [email protected] Professor Daniel Bienstock first joined Columbia University's Industrial Engineering and Operations Research Department in 1989. Professor Bienstock teaches courses on integer programming and optimization. Before joining Columbia University, Professor Bienstock was involved in Combinatorics and Optimization Research at Bellcore. He has also participated in collaborative research with Bell Laboratories (Lucent), AT&T Laboratories, Tellium, Inc. and Lincoln Laboratory on various network design problems. Professor Bienstock's teaching and research interests include combinatorial optimization and integer programming, parallel computing and applications to networking. Professor Bienstock has published in journals such as Math Programming, SIAM and Math of OR. Jose Blanchet Assistant Professor [email protected] Professor Jose Blanchet joined the IEOR Department in Spring 2008. His research interests include applied probability, computational finance, MCMC, queueing theory, rare-event analysis, simulation methodology, and risk theory. Professor Blanchet received his bachelor degree from Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México for Applied Mathematics and Actuarial Science and his masters and Ph.D. from Stanford University for Operations Research. Previously he has taught at Harvard University. Amongst other distinguished awards and honors, Professor Blanchet won the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE) in 2010, the highest honor that any young scientist or engineer can receive from the United States government. Mark Broadie Professor of Business [email protected] Professor Mark Broadie joined Columbia University's Industrial Engineering and Operations Research Department in 1983. His main research areas include the pricing of derivative securities, risk management, and portfolio optimization. -

Pdf from the Consumption of Alcohol and Tobacco

The Sustainability Yearbook 2021 Tackling parity, plastics and petroleum - reflecting on values, anticipating risks and identifying opportunities The Sustainability Yearbook 2021 February 2021 S&P Global spglobal.com/yearbook 2 The Sustainability Yearbook 2021 2021 Annual Corporate Sustainability Assessment 61 7,032 Industries Companies assessed* *As of January 22nd, 2021 215,412 7,326,876 Documents uploaded Data points collected The Sustainability Yearbook 2021 3 The Sustainability Yearbook ISBN 978-3-9525385-0-0 (print) ISBN 978-3-9525385-1-7 (online) Publisher Evan Greenfield, [email protected] Editor Robert Dornau, +41 44 529 51 73 [email protected] Contributors Editorial Board Edoardo Gai Evan Greenfield Nathan Hunt Robert Manjit Jus Rosanna Dornau Brady Copy Editors Director, ESG Operations Corporate Rosanna Brady, Mariano De Lellis, Specialist, Engagement, Lyn Zurbrigg S&P Global S&P Global Production Manager David Sullivan, + 44 207 176 0268 Alexandra [email protected] Mihailescu Cichon Marie Production Office Executive Froehlicher S&P Global Switzerland SA Vice President, Zürich Branch Sales and Marketing, ESG Specialist, Josefstrasse 218 RepRisk S&P Global 8005 Zürich Switzerland Lotte Article Reprints & Permissions Knuckles John Griek S&P Global Switzerland SA Duncan Head of Corporate +41 33 529 51 70 Initiative Lead, Sustainability [email protected] No Plastics in Nature, Assessments, S&P Global WWF International S&P Global 55 Water Street New York, New York 10041. United States General