Social Gaming and Real-Money Gambling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Media in Higher Education: Building Mutually Beneficial Student and Institutional Relationships Through Social Media

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2011 Social Media in Higher Education: Building Mutually Beneficial Student and Institutional Relationships through Social Media. Megan L. Fuller East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Computer Sciences Commons, and the Education Commons Recommended Citation Fuller, Megan L., "Social Media in Higher Education: Building Mutually Beneficial Student and Institutional Relationships through Social Media." (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1275. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1275 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social Media in Higher Education: Building Mutually Beneficial Student and Institutional Relationships through Social Media -------------------- A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Computer & Information Sciences East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Computer Science by Megan Fuller May 2011 -------------------- Dr. Tony Pittarese, Chair Mrs. Jessica Keup Dr. Sally Lee Dr. Edith Seier Keywords: Social Media, Higher Education, Student Teacher Relationships ABSTRACT Social Media in Higher Education: Building Mutually Beneficial Student and Institutional Relationships through Social Media by Megan Fuller Social applications such as Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter have driven the public growth of Web 2.0. -

A Literature Review

The imbalanced state of free-to-play game research: A literature review Kati Alha Tampere University Kanslerinrinne 1 FI-33014 Tampere, Finland +358 40 190 4070 [email protected] ABSTRACT As free-to-play games have increased their economic value, the research interest on them has increased as well. This article looks at free-to-play game research conducted so far through a systematic literature review and an explorative analysis of the documents included in the review. The results highlight an excessive focus especially on behavioral economic studies trying to maximize the player bases and profits, while other aspects, such as meaningful game experiences, cultural and societal implications, or critical review of the phenomena have been left in the marginal. Based on the review results, this article suggests four future agendas to reinforce the lacking areas of free-to-play game research. Keywords free-to-play, freemium, games, literature review, research agendas INTRODUCTION The game industry has changed. Revenue models have shifted from retail products to service relationship between the publisher and the customer (Sotamaa & Karppi 2010). The industry has grown due to changes in the business models and the consumption of games. By offering the game for free, games can reach wider audiences, and by offering in-game content for a fee, companies can still generate considerable income. This revenue model called free-to-play represents one of the most notable forces of change in the game industry. After reaching economic success, the free-to-play revenue model has anchored itself deeply and substantially in the game ecosystem. -

How Mark Zuckerberg Turned Facebook Into the Web's Hottest Platform by Fred Vogelstein 09.06.07 He Didn't Have Much Choice but to Sell

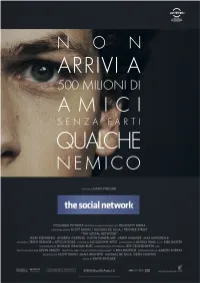

1 COLUMBIA PICTURES Presenta in Associazione con RELATIVITY MEDIA una Produzione SCOTT RUDIN, MICHAEL DE LUCA, TRIGGER STREET un film di DAVID FINCHER (id.) JESSE EISENBERG ANDREW GARFIELD JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE ARMIE HAMMER MAX MINGHELLA Musiche di TRENT REZNOR & ATTICUS ROSS Costumi di JACQUELINE WEST Montaggio di ANGUS WALL, KIRK BAXTER Scenografie di DONALD GRAHAM BURT Direttore della fotografia JEFF CRONENWETH Executive Producers KEVIN SPACEY Tratto dal libro “The Accidental Billionaires” di BEN MEZRICH Sceneggiatura di AARON SORKIN Prodotto da SCOTT RUDIN, DANA BRUNETTI, MICHAEL DE LUCA, CEÁN CHAFFAIN Regia di DAVID FINCHER Data di uscita: 12 novembre 2010 Durata: 120 minuti sonypictures.it Distribuito da Sony Pictures Releasing Italia 2 CARTELLO DOPPIATORI - THE SOCIAL NETWORK UFFICIO STAMPA Cristiana Caimmi Dialoghi Italiani Valerio Piccolo Direzione del Doppiaggio Alessandro Rossi Voci MARK ZUCKERBERG – Davide Perino EDUARDO SAVERIN – Lorenzo de Angelis SEAN PARKER – Gabriele Lopez CAMERON e TYLER WINKEL VOSS – Marco Vivio DIVYA NARENDRA – Gianfranco Miranda ARICA ALBRIGHT – Chiara Gioncardi Fonico di Mix Alessandro Checcacci Fonico di Doppiaggio Stefano Sala Assistente al Doppiaggio Silvia Alpi Doppiaggio eseguito presso CDC SEFIT GROUP 3 Note di Produzione Ogni epoca ha i suoi visionari, che sulla scia del loro genio, lasciano un mondo cambiato. Ma tutto ciò raramente avviene senza che ci siano contrasti. Nel film The Social Network, il regista David Fincher e lo sceneggiatore Aaron Sorkin raccontano il momento in cui è stato creato Facebook, il fenomeno sociale più rivoluzionario del nuovo secolo, attraverso lo scontro di alcuni giovani brillanti che affermano di aver preso ognuno parte alla nascita del progetto. Il risultato è il racconto di un dramma che alterna la creatività alla distruzione, in cui non c'è un solo punto di vista ma un duello narrativo che rispecchia perfettamente la realtà delle relazioni sociali dei nostri giorni. -

Writing in the Flow: Assembling Tactical Rhetorics in an Age of Viral Circulation

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Dustin Wayne Edwards Candidate for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ______________________________________ James Porter, Director ______________________________________ Heidi McKee, Reader ______________________________________ Jason Palmeri, Reader ______________________________________ Michele Simmons, Reader ______________________________________ James Coyle, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT WRITING IN THE FLOW: ASSEMBLING TACTICAL RHETORICS IN AN AGE OF VIRAL CIRCULATION by Dustin W. Edwards From prompts to share, update, and retweet, social media platforms increasingly insist that creating widespread circulation is the operative goal for networked writing. In response, researchers from multiple disciplines have investigated digital circulation through a number of lenses (e.g., affect theory, transnational feminism, political economy, public sphere theory, and more). In rhetoric and writing studies, scholars have argued that writing for circulation—i.e., envisioning how one’s writing may gain speed, distance, and momentum—should be a prime concern for teachers and researchers of writing (e.g., Gries, 2015; Ridolfo & DeVoss, 2009; Porter, 2009; Sheridan, Ridolfo, & Michel, 2012). Such work has suggested that circulation is a consequence of rhetorical delivery and, as such, is distinctly about futurity. While a focus on writing for circulation has been productive, I argue that that writing in circulation can be equally productive. Challenging the tendency to position circulation as an exclusive concern for delivery, this project argues that circulation is not just as an end goal for rhetorical activity but also as a viable inventional resource for writers with diverse rhetorical goals. To make this case, I construct a methodology of assemblage to retell stories of tactical rhetorics. -

![Contents [Edit] History](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6727/contents-edit-history-2696727.webp)

Contents [Edit] History

Zynga (English pronunciation: /ñzųŋŪŢ/) is a Web 2.0-based social network game developer located in San Francisco, California, United States.[1] The company develops browser-based games that work both stand-alone and as application widgets on social networking websites such as Facebook and MySpace. Contents [hide] y 1 History y 2 Business model o 2.1 Platinum Purchase Program y 3 Studios and subsidiaries o 3.1 Current y 4 Controversies o 4.1 Games 4.1.1 Spam concerns 4.1.2 Game quality 4.1.3 Replication of existing games 4.1.4 Viability o 4.2 Scam ads o 4.3 Other criticism y 5 Funding y 6 Games o 6.1 Games Discontinued y 7 Zynga.org y 8 References y 9 External links [edit] History Zynga was founded in July 2007 by Mark Pincus, Michael Luxton, Eric Schiermeyer, Justin Waldron, Andrew Trader, and Steve Schoettler.[2] They received USD $29 million in venture finance from several firms, led by Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers in July 2008, at which time they appointed former Electronic Arts Chief Creative Officer Bing Gordon to the board.[3] At that time, they also bought YoVille, a large virtual world social network game.[3] According to their website, as of December 2009, they had 60 million unique daily active users.[4] The company name '"Zynga" comes from an American bulldog once owned by Mark Pincus.[5] As of September 2010, Zynga had over 750 employees.[6] On 17 February 2010, Zynga opened Zynga India in Bangalore, the company¶s first office outside the United States.[7] On 18 March 2010, Zynga confirmed that they will open a second -

Social Games

CASE: EC-39 DATE: 09/15/10 SOCIAL GAMES The social games market potential seems truly stunning. Assuming ½ of the Internet world may end up on Facebook and ½ of those Facebook users will try a social game at some point, we can say that ¼ of the online world is an approachable market. Yet only 1 to 3 percent of players of social games tend to be monetized, so we’re still at the tip of the iceberg in terms of revenue opportunity. —Tim Chang, principal Norwest Venture Partners In November 2009, 70 million people played a game called FarmVille on Facebook where players could pretend to be a virtual farmer, planting and harvesting fruits and vegetables and moving up to other levels by inviting their Facebook friends to be their neighbors. Similarly, 26 million active users per month played a game called Mafia Wars on Facebook where players could start a mafia family with friends, run multiple crime “businesses,” then fight to be the ruling family (Exhibit 1). These types of popular online games were called “social games,” games people played on social networks like Facebook, MySpace, Hi5, Orkut, and Bebo, with the key motive of socializing with friends and/or meeting new people, with Facebook as the dominant social network in the social gaming space. Social games were generally simple games that anyone could play. Unlike traditional video games, they were less about “killer graphics and quicksilver hand-eye coordination, and more about connecting with friends.”1 And because the mainstream was being lured into social gaming, it was becoming the fastest-growing game market, increasingly popular on social networking sites. -

Saskatoon Winter 2012 Hotlist Download

Skylight Books – Hotlist Winter 2011/2012 SKYLIGHT BOOKS Skylight Books is the wholesale division of McNally Robinson Booksellers. With a focus on serving Libraries and Schools in our region, we pride ourselves on personal service and local titles in combination with the price and selection of a national supplier. Like all the national library wholesalers, Skylight offers: · MARC records · Online ordering · Hotlists · Aggressive discounts In addition, Skylight offers: · Regional perspective and titles reflected in our recommendations. · Personalized service · The satisfaction of spending your tax dollars in your community. When thinking about your buying decisions, please consider us. We offer all the advantages of a national supplier while retaining the service of a local company. Thank You, Tory McNally Phone: 306-955-1477 Fax: 306-955-3977 Email: [email protected] Pg 1 Skylight Books – Hotlist Winter 2011/2012 WORKING TOGETHER Hotlist Orders Our Hotlist is produced three times a year for our Library customers and is available in print and on-line through our institutional website skylightbooks.ca. A copy of the print version is mailed to all of our Library customers. Spreadsheets by title and by author are available for download from the website or contact your Skylight representative to receive copies via email. Hotlist orders should be completed and sent by the deadline date indicated on the Hotlist hard copy and on our website. Please contact us if an extension to this deadline is required to be sure you will not miss out on our pre-publication ordering. Hotlist orders placed on-line should only contain items chosen from the Hotlist. -

Gaming in the Mobile Internet

This is the author’s version of the chapter published in: Garry Crawford, Victoria K Gosling, Ben Light, Eds., Online Gaming in Context: The social and cultural significance of online games. Routledge, 2011. Games in the Mobile Internet: Understanding Contextual Play in Flickr and Facebook Frans Mäyrä INTRODUCTION The social and cultural phenomena related to Internet gaming have received their fair share of attention, particularly through numerous studies of massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs). Also mobile games have their own research and developer communities, but the research work related to mobile games has so far been dominated by their technical and design challenges and researchers have not been particularly interested in their social aspects – in contrast to the numerous studies that have focused on mobile communication through text messages and other means (the recent Handbook of Mobile Communication Studies dedicates one out of its 32 chapters to mobile games and entertainment; see Katz & Acord 2008). This chapter will approach contemporary developments in social and mobile gaming as an Internet phenomena. Looking back, there has been a noticeable difference between Western usage patterns of the Internet, mostly focused on the personal computer, and Japan, where mobile phone is the predominant access point to the Internet services. Recently also Western countries have been introduced with new generations of Internet-capable smartphones, including Apple iPhone, Nokia E and N- series, BlackBerry devices and others, which reportedly have already been associated with a noticeable upsurge in the mobile Internet usage, and some analysts have claimed that now finally “mobile internet has reached a critical mass”.1 The relative share of mobile browsers in the Internet usage statistics nevertheless still remains in minority. -

Taking on the Mob – Protecting Your Social Game with Trade Dress

©iStockphoto.com/Gerald Senger ©iStockphoto.com/Gerald Feature By Theodore K Stream, Emma D Enriquez and Ben A Eilenberg Taking on the mob – protecting your social game with trade dress Social game developers operate in a fast-moving, competitive marketplace, where traditional applications of trademark law may no longer provide comprehensive protection. However, recent disputes involving Mafia-themed games suggest that all is not lost 64 World Trademark Review April/May 2011 www.WorldTrademarkReview.com The popularity of social games has boomed over the past few years. As revenue is generated by capturing an audience of gamers and The more distinctive a game selling products to them, early entry is often critical to establishing a developer’s foothold. Once an audience is captured for a particular arrangement, the more likely game, the opportunity to cross-advertise other games and products is effectively created. Equally important is protecting the intellectual that the look and feel of the property inherent in the offering – requiring new approaches to trademark law application. game will be protected under Trademark law is designed to protect the identification of a game with its source. In an ideal world, all games and developer trade dress theories marks would be so distinctive that there would be no likelihood of confusion between them and their sources; but amid the explosion of games and the rush to bring them to market, this simply isn’t always the case. In addition to natural confusion resulting from industry growth, competitors sometimes intentionally replicate successful games in an effort to capitalise on their popularity. -

Game Design by Numbers

Game Design by Numbers: Instrumental Play and the Quantitative Shift in the Digital Game Industry by Jennifer R. Whitson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario © 2012 Jennifer R. Whitson Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1 Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94236-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-94236-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Voters Make Their Choices

Volume 39 Number 45 Thursday, November 8, 2018 32 Pages | 75¢ Voters make their choices Turnout was heavier than “I think, perhaps, over normal throughout the area the years, I have become for a mid-term election year more widely known coun- as voters made their choices ty wide,” Johnson said. Tuesday. “With my work with the In Randolph County, Re- Regional Office of Edu- publican Melanie Johnson cation and other things, was victorious over Demo- I’ve come in contact with crat Bobby Klausing in the people all over the county. race for County Clerk Pat There might have been Laramore’s seat. some familiarity with who Melanie Johnson Marc Kiehna Steve Bareis “It was a good race,” John- I was.” son said. “I was very pleased County Commissioner with the results. I felt the Marc Kiehna, who also turnout was very good. I’m won in this election, looking forward to what weighed in on Johnson comes next with learning being voted clerk. more about what I need to “I’m excited Melanie do within the office.” Johnson will be doing the Johnson received 54 per- clerk’s job,” Kiehna said. cent of the 12,408 county “I think she is a fine ad- vote totals and held a 6,660 dition to the courthouse.” to 5,418 advantage over Kiehna, a Republican, Klausing. won handily over Voss, a “I just want to thank every- Democrat, who is also the body,” Johnson said. “Bobby outgoing assessor. called me (Wednesday morn- Kiehna received 54 per- ing), and I spoke with him cent of the 12,088 votes and wished him the best in cast in the county com- whatever he chooses to do.” missioner race. -

GAMING on FACEBOOK Understand It, and Profit from It ! 1.OVERVIEW - Gaming on Facebook 200 Million Potential Gamers, 3.6$ Billion Market in 2012

GAMING ON FACEBOOK Understand it, and profit from it ! 1.OVERVIEW - Gaming on Facebook 200 million potential gamers, 3.6$ billion market in 2012 Facebook has over 400 million users per audience per month, to play games supported month, out of which 200 million logon every by the social networking site. day for sessions lasting around 55 minutes each. Therefore, being present on this market not only Nearly 75% of these are playing one form of is something to desire, but is an opportunity that social games in a market that reached you shouldn’t miss. nearly 1 billion $ in 2009 and will reach 3.6$ billion in 2012. And some companies didn’t miss it. Each month, 82 million people are playing Farmville, 25 This creates a huge market for social games, million people are playing Zynga’s Texas which is currently in its inception phase. If the Hold-Em Poker on Facebook, 25 million are increase rate of social sites is now rather playing Mafia Wars, 24 million are breeding fish moderate, more and more of the current in Happy Aquarium, and the market is just customers are starting to consume social games, developing. thus injecting money into a system that offers them an excellent platform for finding and Current market is estimated to reach near playing games with their friends. Also, 1 billion USD for 2010, and it’s set to reach 3.6 advergaming on these platforms starts to gain billion USD until 2012. If until recently the traction, meaning that brands that dare to use monetization of social media was a thing to social platforms are getting a bigger ROI from discuss, now the vast availability of payment their advertising and marketing investments than methods leads to a fast growth.