Property and Sovereignty Imbricated: Why Religion Is Not an Excuse to Discriminate in Public Accommodations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lydia Polgreen Editor-In-Chief, Huffpost Media Masters – April 4, 2019 Listen to the Podcast Online, Visit

Lydia Polgreen Editor-in-Chief, HuffPost Media Masters – April 4, 2019 Listen to the podcast online, visit www.mediamasters.fm Welcome to Media Masters, a series of one to one interviews with people at the top at the media game. Today I’m here in New York and joined by Lydia Polgreen, editor-in-chief of HuffPost. Appointed in 2016, she previously spent 15 years at the New York Times where she served as foreign correspondent in Africa and Asia. She received numerous awards for her work, including a George Polk award for her coverage of ethnic violence in Darfur in 2006. Lydia carried out a number of roles at the Times, most recently as editorial director of NYT global. She’s also a board member at Columbia Journalism Review, and the Committee to Protect Journalists. Lydia, thank you for joining me. It’s a pleasure to be here. So Lydia, editor-in-chief of HuffPost, obviously an iconic brand with an amazing history. Where are you going to take it next? Well, I think past is prologue and the future is unknown. Oh, that’s good. I like that already. We’re starting off on the deeply profound. Continue! Well, I think for media right now, it’s a really fascinating moment of both rediscovery of our roots – and those roots really lie in what’s at the core of journalism, which is exposing things that weren’t meant to be known, or that people, important people especially, don’t want to be known, and bringing them to light. -

John C. Andrews

Verizon Media EMEA Limited 5-7 Point Square, North Wall Quay Dublin 1, Ireland Tel.: +353 1 866 3100 Fax: +353 1 866 3101 Reg: 426324 Commissioner Didier Reynders EUROPEAN COMMISSION JUSTICE Rue de la Loi, 200 1049 Brussels BELGIUM 2 April 2020 Dear Commissioner Reynders, I refer to the letter dated 24 March addressed to our CEO Mr. Guru Gowrappan. Verizon Media, the parent company of Yahoo, HuffPost, AOL and TechCrunch, is focused on making a positive impact on society during this challenging time. We are committed to providing our users with information they can trust and keeping our platforms safe from malicious actors who may seek to take advantage of the COVID-19 crisis. We have carefully monitored the COVID-19 public health emergency and are scrutinizing all ads with an increased focus on sensitivity to public health guidance and risks. Our Ad Policies prohibit ads that claim that any medicine, surgical treatment, or device can prevent or cure coronavirus. Our automated systems flag high-risk ads for manual review and those that violate policy, including COVID-19-related ads, are blocked. We recognize that our 900 million users across the globe rely on us to deliver accurate, reliable news and information. To this end, we have created a coronavirus hub, covid19.yahoo.com, across the Yahoo ecosystem (News, Finance, Sports, Lifestyle & Entertainment), that includes news in real-time about the pandemic across the globe. There is specific content for specific markets, including France (fr.yahoo.com/topics/liste-coronavirus-france), Italy (it.yahoo.com/topics/coronavirus), Germany (de.yahoo.com/topics/Coronavirus), Spain (es.yahoo.com/topics/coronavirus) and the UK (uk.yahoo.com/topics/coronavirus-news). -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

Liberal Parents, Liberal Children | Huffpost

Liberal Parents, Liberal Children | HuffPost US EDITION T H E B LOG 01/26/2009 05:12 am ET| Updated May 25, 2011 Liberal Parents, Liberal Children By Marty Kaplan When it comes to politics, today’s college freshmen resemble their baby boomer parents of 40 years ago in all ways except two. One way makes perfect sense; the other is a puzzle. The evidence about kids and their parents isn’t anecdotal; it’s documented in a study just released by UCLA’s Higher Education Research Institute, which has been investigating the attitudes of a massive national sample of American freshmen since the 1960s. More freshmen today say they frequently discuss politics than at any time since Lyndon Johnson announced that he wouldn’t run for re-election. Just since 2000, that slice of young people — 35.6 percent — has more than doubled, and it even exceeds by a couple of points the previous high-water mark, when Richard Nixon was elected president. When you add in the number of today’s freshmen who say they occasionally discuss politics, you’re talking about nearly 86 percent of them, another record. Today, the proportion of freshmen calling themselves liberal has hit 31 percent, the highest it’s been in 35 years. At the same time, the number of students calling their political views middle-of-the-road has hit an all-time low, just over 43 percent, territory it hasn’t been in since 1970. Only one out of five students today describes him or herself as conservative, an erosion of more than two points since the year before. -

Status Threat, Social Concerns, and Conservative Media: a Look at White America and the Alt-Right

societies Article Status Threat, Social Concerns, and Conservative Media: A Look at White America and the Alt-Right Deena A. Isom 1,* , Hunter M. Boehme 2 , Toniqua C. Mikell 3, Stephen Chicoine 4 and Marion Renner 5 1 Department of Criminology & Criminal Justice and African American Studies Program, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC 29208, USA 2 Department of Criminal Justice, North Carolina Central University, Durham, NC 27707, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Crime and Justice Studies, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, Dartmouth, MA 02747, USA; [email protected] 4 Bridge Humanities Corp Fellow and Department of Sociology, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC 29208, USA; [email protected] 5 Department of Criminology & Criminal Justice, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC 29208, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Racial and ethnic division is a mainstay of the American social structure, and today these strains are exacerbated by political binaries. Moreover, the media has become increasingly polarized whereby certain media outlets intensify perceived differences between racial and ethnic groups, political alignments, and religious affiliations. Using data from a recent psychological study of the Alt-Right, we assess the associations between perceptions of social issues, feelings of status threat, trust in conservative media, and affiliation with the Alt-Right among White Americans. We find concern over more conservative social issues along with trust in conservative media explain a large Citation: Isom, D.A.; Boehme, H.M.; portion of the variation in feelings of status threat among White Americans. Furthermore, more Mikell, T.C.; Chicoine, S.; Renner, M. -

Presidential Fatigue Hits Gen Z Users, Shows Oath's News Data

Presidential Fatigue Hits Gen Z Users, Shows Oath’s News Data By [oath News Team] -- TBC Source: oath News Analytics - Longitudinal Trends across Generation X, Millennial, and Generation Z The common assumption is that anyone engaged in current events today is focused on U.S. politics, but the data shows that it actually depends on your generation. Gen Z is focused on a diverse array of issues and are largely isolated from the obsessive focus on national politics seen in other generations. Since they are the next generation to come online as voters (beginning in 2018 for the oldest Gen Zers), should we be concerned for the next election? Oath News data on longitudinal trends across Gen X, Millennials and Gen Z show that while the November 8th presidential election drew people from all age groups on presidential topics, trends for Gen X and Millennial are also similar. Gen Z has the most diverse interest over time and was the only group with significant discussion in international politics and society related stories. The US elections, Brexit, France’s landmark presidential election, and the unfortunate terrorist attacks over the past year prompted us to dig deeper into our news platform, to see how these events may have impacted our communities. This analysis was conducted through a review of over 100 million comments, of which 3 million were analyzed to define the top 10 trending US hosted articles per month ranked by total comments. Included in this analysis were comments generated within the flagship mobile app Newsroom iOS and Android, and across our biggest news platforms Yahoo.com and Yahoo News. -

Public Radio International, Lyndon Johnson's Presidency and the War

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Public Programs application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/public/media- projects-production-grants for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Public Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: LBJ’s War: An Oral History Institution: Public Radio International, Inc. Project Director: Melinda Ward Grant Program: Media Projects Production 400 7th Street, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8269 F 202.606.8557 E [email protected] www.neh.gov PUBLIC RADIO INTERNATIONAL (PRI) Request to the National Endowment for the Humanities “LBJ’S War: An Oral History” Project Narrative – January 2016 A. NATURE OF THE REQUEST Public Radio International (PRI) requests a grant of $166,450 in support of LBJ’s War , an innovative oral history project to be produced in partnership with independent radio producer Stephen Atlas. LBJ’s War presents the story of how the U.S. -

The Surprisingly Contentious History of Executive Orders | Huffpost

4/2/2020 The Surprisingly Contentious History Of Executive Orders | HuffPost Ben Feuer, Contributor Chairman, California Appellate Law Group The Surprisingly Contentious History Of Executive Orders Cries of “unprecedented” executive action on both sides are more histrionic than historical. 02/02/2017 04:59 am ET | Updated Feb 03, 2017 Despite howls that Presidents Trump and Obama both issued “unprecedented” executive orders, presidents have embraced executive actions to enact controversial policies since the dawn of the Republic. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/the-surprisingly-contentious-history-of-executive-orders_b_58914580e4b04c35d583546e 1/8 4/2/2020 The Surprisingly Contentious History Of Executive Orders | HuffPost NICHOLAS KAMM/AFP/GETTY IMAGES Recently, USA Today savaged President Trump’s executive orders since taking office, from encouraging Keystone XL approval to altering immigration policy, as an “unprecedented blizzard.” In 2014, the Washington Post raked President Obama for his Deferred Action immigration directives, more commonly called DACA and DAPA, deeming them “unprecedented” and “sweeping,” while Ted Cruz published an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal lashing Obama’s “imperial” executive order hiking the minimum wage for federal contractors as one with “no precedent.” A 2009 piece in Mother Jones lamented a President George W. Bush executive order allowing former-presidents and their families to block the release of presidential records as — you guessed it — “unprecedented.” With all the talk of precedent, you might think executive orders historically did little more than set the White House lawn watering schedule. But the reality is that presidents have long employed executive actions to accomplish strikingly controversial objectives without congressional approval. -

Yoohoo! Yahoo! | Huffpost

Yoohoo! Yahoo! | HuffPost US EDITION THE BLOG Yoohoo! Yahoo! By Marty Kaplan 02/15/2006 04:54 pm ET | Updated May 25, 2011 If an American enters “Li Zhi” or “Shi Tao” in the search engine at Yahoo! News, more than 400 stories turn up, none of them flattering to Yahoo! But those articles won’t appear if you search for those words, or countless others deemed subversive by officials, on a computer in China. For nearly a decade, not only has Yahoo! allowed the Chinese version of its search engine to be censored; worse, it has also turned over to Chinese state security the IP and e-mail addresses they have sought in order to nail and jail dissidents. When an American-based multinational is complicit with a police state’s worst practices, at the very least it takes the zing out of the exclamation mark in its branding. Shi Tao, 37, was a reporter for the business daily, Dangdai Shang Bao. A year ago, he was sentenced by Beijing to 10 years in prison for “divulging state secrets abroad.” His offense was e-mailing to non-Chinese Web sites the warning that the Beijing government told his newspaper and others not to cover the 15th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre. According to the text of the verdict, it was Yahoo! Hong Kong that enabled Chinese investigators to track the posting on a foreign Web site to Shi’s yahoo.com.cn e-mail account and to the IP address of his computer. This month, another such case was reported. -

Huffpost: Coronavirus Stimulus October 6 - 10, 2020 - 1000 US Registered Voters

HuffPost: Coronavirus Stimulus October 6 - 10, 2020 - 1000 US Registered Voters 1. Should Congress Pass COVID Stimulus Do you think Congress should or should not pass a new economic stimulus bill in response to the coronavirus pandemic? Gender Age (4 category) Race (4 category) Total Male Female 18-29 30-44 45-64 65+ White Black Hispanic Other It should 74% 80% 70% 73% 78% 73% 74% 70% 87% 86% 85% It should not 10% 8% 12% 11% 9% 11% 11% 13% 4% 3% 3% Not sure 15% 12% 18% 16% 13% 17% 15% 17% 8% 11% 12% Totals 99% 100% 100% 100% 100% 101% 100% 100% 99% 100% 100% Unweighted N (997) (427) (570) (124) (196) (411) (266) (806) (79) (53) (59) Party ID 2016 Vote Family Income (3 category) Census Region Total Dem Ind Rep Clinton Trump < $50K $50-100K $100K+ Northeast Midwest South West It should 74% 92% 73% 57% 91% 59% 82% 69% 73% 83% 71% 70% 78% It should not 10% 2% 7% 22% 3% 19% 5% 15% 17% 11% 15% 9% 7% Not sure 15% 6% 20% 21% 6% 22% 13% 16% 10% 6% 13% 21% 15% Totals 99% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 99% 100% 100% Unweighted N (997) (369) (333) (295) (391) (336) (360) (299) (195) (196) (195) (381) (225) 1 HuffPost: Coronavirus Stimulus October 6 - 10, 2020 - 1000 US Registered Voters 2. How Important is COVID Stimulus How important is it to you personally that Congress passes a new economic stimulus bill? Asked of those who think Congress should pass a COVID stimulus bill Gender Age (4 category) Race (4 category) Total Male Female 18-29 30-44 45-64 65+ White Black Hispanic Other Very important 58% 54% 62% 65% 56% 57% 56% 54% 64% 69% -

071107 I Believe for Every Drop of Rain That Falls, a Flower Grows

I Believe for Every Drop of Rain That Falls, A Flower Grows | HuffPost US EDITION THE BLOG I Believe for Every Drop of Rain That Falls, A Flower Grows By Marty Kaplan 07/11/2007 11:19 am ET | Updated May 25, 2011 “I wouldn’t ask a mother or a dad — I wouldn’t put their son in harm’s way if I didn’t believe this was necessary for the security of the United States and the peace of the world. I strongly believe it, and I strongly believe we’ll prevail. And I strongly believe that democracy will trump totalitarianism every time. That’s what I believe. And those are the belief systems on which I’m making decisions that I believe will yield the peace.” — George W. Bush, Cleveland, July 10, 2007 Who gives a flying fig for what you believe, Mr. President? You believed trading Sammy Sosa to the White Sox was a good move. You believed Saddam was making nukes from Nigerien yellowcake. You believed Senators of both parties would acclaim Harriet Miers as a “superb choice” for the Supreme Court,” an American of “unwavering devotion to the Constitution and laws of our country.” You said you had faith in General Casey (until you fired him). You keep telling us you have faith in Alberto Gonzales. We know you believe in a Higher Power, Mr. Bush — hey, if AA works for you, you go, guy — but why should any American mother or dad let you put their son in harm’s way just because you “strongly believe” that his being wasted by a roadside IED in an Islamic civil war makes the world more peaceful and the United States more secure? This “belief” thing runs alarmingly deep. -

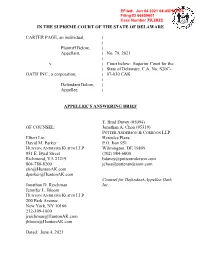

Answering Brief

EFiled: Jun 04 2021 04:45PM EDT Filing ID 66659601 Case Number 79,2021 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE CARTER PAGE, an individual, ) ) Plaintiff Below, ) Appellant, ) No. 79, 2021 ) v. ) Court below: Superior Court for the ) State of Delaware, C.A. No. S20C- OATH INC., a corporation, ) 07-030 CAK ) Defendant Below, ) Appellee. ) APPELLEE’S ANSWERING BRIEF T. Brad Davey (#5094) OF COUNSEL: Jonathan A. Choa (#5319) POTTER ANDERSON & CORROON LLP Elbert Lin Hercules Plaza David M. Parker P.O. Box 951 HUNTON ANDREWS KURTH LLP Wilmington, DE 19899 951 E. Byrd Street (302) 984-6000 Richmond, VA 23219 [email protected] 804-788-8200 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Defendant-Appellee Oath Jonathan D. Reichman Inc. Jennifer L. Bloom HUNTON ANDREWS KURTH LLP 200 Park Avenue New York, NY 10166 212-309-1000 [email protected] [email protected] Dated: June 4, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS NATURE OF THE PROCEEDINGS ........................................................................ 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................................................................. 5 STATEMENT OF FACTS ........................................................................................ 7 I. The Yahoo Article ................................................................................. 7 II. The HuffPost Articles ............................................................................ 8 III. Page’s prior lawsuit. .............................................................................