Predation Drives Interpopulation Differences in Parental Care Expression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

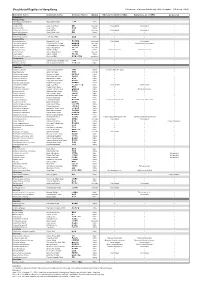

No. Area Post Office Name Zip Code Address Telephone No. Same Day

Zip No. Area Post Office Name Address Telephone No. Same Day Flight Cut Off Time * Code Pingtung Minsheng Rd. Post No. 250, Minsheng Rd., Pingtung 900-41, 1 Pingtung 900 (08)7323-310 (08)7330-222 11:30 Office Taiwan 2 Pingtung Pingtung Tancian Post Office 900 No. 350, Shengli Rd., Pingtung 900-68, Taiwan (08)7665-735 10:00 Pingtung Linsen Rd. Post 3 Pingtung 900 No. 30-5, Linsen Rd., Pingtung 900-47, Taiwan (08)7225-848 10:00 Office No. 3, Taitang St., Yisin Village, Pingtung 900- 4 Pingtung Pingtung Fusing Post Office 900 (08)7520-482 10:00 83, Taiwan Pingtung Beiping Rd. Post 5 Pingtung 900 No. 26, Beiping Rd., Pingtung 900-74, Taiwan (08)7326-608 10:00 Office No. 990, Guangdong Rd., Pingtung 900-66, 6 Pingtung Pingtung Chonglan Post Office 900 (08)7330-072 10:00 Taiwan 7 Pingtung Pingtung Dapu Post Office 900 No. 182-2, Minzu Rd., Pingtung 900-78, Taiwan (08)7326-609 10:00 No. 61-7, Minsheng Rd., Pingtung 900-49, 8 Pingtung Pingtung Gueilai Post Office 900 (08)7224-840 10:00 Taiwan 1 F, No. 57, Bangciou Rd., Pingtung 900-87, 9 Pingtung Pingtung Yong-an Post Office 900 (08)7535-942 10:00 Taiwan 10 Pingtung Pingtung Haifong Post Office 900 No. 36-4, Haifong St., Pingtung, 900-61, Taiwan (08)7367-224 Next-Day-Flight Service ** Pingtung Gongguan Post 11 Pingtung 900 No. 18, Longhua Rd., Pingtung 900-86, Taiwan (08)7522-521 10:00 Office Pingtung Jhongjheng Rd. Post No. 247, Jhongjheng Rd., Pingtung 900-74, 12 Pingtung 900 (08)7327-905 10:00 Office Taiwan Pingtung Guangdong Rd. -

Cycling Taiwan – Great Rides in the Bicycle Kingdom

Great Rides in the Bicycle Kingdom Cycling Taiwan Peak-to-coast tours in Taiwan’s top scenic areas Island-wide bicycle excursions Routes for all types of cyclists Family-friendly cycling fun Tourism Bureau, M.O.T.C. Words from the Director-General Taiwan has vigorously promoted bicycle tourism in recent years. Its efforts include the creation of an extensive network of bicycle routes that has raised Taiwan’s profile on the international tourism map and earned the island a spot among the well-known travel magazine, Lonely Planet’s, best places to visit in 2012. With scenic beauty and tasty cuisine along the way, these routes are attracting growing ranks of cyclists from around the world. This guide introduces 26 bikeways in 12 national scenic areas in Taiwan, including 25 family-friendly routes and, in Alishan, one competition-level route. Cyclists can experience the fascinating geology of the Jinshan Hot Spring area on the North Coast along the Fengzhimen and Jinshan-Wanli bikeways, or follow a former rail line through the Old Caoling Tunnel along the Longmen-Yanliao and Old Caoling bikeways. Riders on the Yuetan and Xiangshan bikeways can enjoy the scenic beauty of Sun Moon Lake, while the natural and cultural charms of the Tri-Mountain area await along the Emei Lake Bike Path and Ershui Bikeway. This guide also introduces the Wushantou Hatta and Baihe bikeways in the Siraya National Scenic Area, the Aogu Wetlands and Beimen bikeways on the Southwest Coast, and the Round-the-Bay Bikeway at Dapeng Bay. Indigenous culture is among the attractions along the Anpo Tourist Cycle Path in Maolin and the Shimen-Changbin Bikeway, Sanxiantai Bike Route, and Taiyuan Valley Bikeway on the East Coast. -

Cambodian Journal of Natural History

Cambodian Journal of Natural History Artisanal Fisheries Tiger Beetles & Herpetofauna Coral Reefs & Seagrass Meadows June 2019 Vol. 2019 No. 1 Cambodian Journal of Natural History Editors Email: [email protected], [email protected] • Dr Neil M. Furey, Chief Editor, Fauna & Flora International, Cambodia. • Dr Jenny C. Daltry, Senior Conservation Biologist, Fauna & Flora International, UK. • Dr Nicholas J. Souter, Mekong Case Study Manager, Conservation International, Cambodia. • Dr Ith Saveng, Project Manager, University Capacity Building Project, Fauna & Flora International, Cambodia. International Editorial Board • Dr Alison Behie, Australia National University, • Dr Keo Omaliss, Forestry Administration, Cambodia. Australia. • Ms Meas Seanghun, Royal University of Phnom Penh, • Dr Stephen J. Browne, Fauna & Flora International, Cambodia. UK. • Dr Ou Chouly, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State • Dr Chet Chealy, Royal University of Phnom Penh, University, USA. Cambodia. • Dr Nophea Sasaki, Asian Institute of Technology, • Mr Chhin Sophea, Ministry of Environment, Cambodia. Thailand. • Dr Martin Fisher, Editor of Oryx – The International • Dr Sok Serey, Royal University of Phnom Penh, Journal of Conservation, UK. Cambodia. • Dr Thomas N.E. Gray, Wildlife Alliance, Cambodia. • Dr Bryan L. Stuart, North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, USA. • Mr Khou Eang Hourt, National Authority for Preah Vihear, Cambodia. • Dr Sor Ratha, Ghent University, Belgium. Cover image: Chinese water dragon Physignathus cocincinus (© Jeremy Holden). The occurrence of this species and other herpetofauna in Phnom Kulen National Park is described in this issue by Geissler et al. (pages 40–63). News 1 News Save Cambodia’s Wildlife launches new project to New Master of Science in protect forest and biodiversity Sustainable Agriculture in Cambodia Agriculture forms the backbone of the Cambodian Between January 2019 and December 2022, Save Cambo- economy and is a priority sector in government policy. -

TAO RESIDENTS' PERCEPTIONS of SOCIAL and CULTRUAL IMPACTS of TOURISM in LAN-YU, TAIWAN Cheng-Hsuan Hsu Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 12-2006 TAO RESIDENTS' PERCEPTIONS OF SOCIAL AND CULTRUAL IMPACTS OF TOURISM IN LAN-YU, TAIWAN Cheng-hsuan Hsu Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Recreation, Parks and Tourism Administration Commons Recommended Citation Hsu, Cheng-hsuan, "TAO RESIDENTS' PERCEPTIONS OF SOCIAL AND CULTRUAL IMPACTS OF TOURISM IN LAN-YU, TAIWAN" (2006). All Theses. 47. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/47 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TAO RESIDENTS’ PERCEPTIONS OF SOCIAL AND CULTRUAL IMPACTS OF TOURISM IN LAN-YU, TAIWAN _________________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University _________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Park, Recreation, and Tourism Management _________________________________________________________ by Cheng-Hsuan Hsu December 2006 _________________________________________________________ Accepted by: Dr. Kenneth F. Backman, Committee Chair Dr. Sheila J. Backman Dr. Francis A. McGuire ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to investigate residents’ perceptions of the social and cultural impacts of tourism on Lan-Yu (Orchid Island). More specifically, this study examines Lan-Yu’s aboriginal residents’ (The Tao) perceptions of social and cultural impacts of tourism. Systematic sampling and a survey questionnaire procedure was employed in this study. After the factor analysis, three underlying dimensions were found when examining Tao residents’ perceptions of social and cultural impacts of tourism, and they were named: positive cultural effects, negative cultural effects, and negative social effects. -

Sexual Size Dimorphism and Feeding Ecology of Eutropis Multifasciata (Reptilia: Squamata: Scincidae) in the Central Highlands of Vietnam

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 9(2):322−333. Submitted: 8 March 2014; Accepted: 2 May 2014; Published: 12 October 2014. SEXUAL SIZE DIMORPHISM AND FEEDING ECOLOGY OF EUTROPIS MULTIFASCIATA (REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SCINCIDAE) IN THE CENTRAL HIGHLANDS OF VIETNAM 1, 5 2 3 4 CHUNG D. NGO , BINH V. NGO , PHONG B. TRUONG , AND LOI D. DUONG 1Faculty of Biology, College of Education, Hue University, Hue, Thua Thien Hue 47000, Vietnam, 2Department of Life Sciences, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Tainan 70101, Taiwan, e-mail: [email protected] 3Faculty of Natural Sciences and Technology, Tay Nguyen University, Buon Ma Thuot, Dak Lak 55000, Vietnam 4College of Education, Hue University, Hue, Thua Thien Hue 47000, Vietnam 5Corresponding author, e-mail:[email protected] Abstract.—Little is known about many aspects of the ecology of the Common Sun Skink, Eutropis multifasciata (Kuhl, 1820), a terrestrial viviparous lizard found in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. We measured males and females to determine whether this species exhibits sexual size dimorphism and whether there was a correlation between feeding ecology and body size. We also examined spatiotemporal and sexual variations in dietary composition and prey diversity index. We used these data to examine whether the foraging pattern of these skinks corresponded to the pattern of a sit-and-wait predator or a widely foraging predator. The average snout-vent length (SVL) was significantly larger in adult males than in adult females. When SVL was taken into account as a covariate, head length and width and mouth width were larger in adult males than in adult females. -

No More Striving Alone, Together, We Will Define the Styles of This Generation

IPCF 2020 Issue magazine May 27 2020 May Issue 27 Issue May 2020 pimasaodan namen Life, with Indigenous Peoples with Indigenous Life, No more striving alone, together, we will define the styles of this generation. Words from Publisher Editorial ya mikepkep o vayo aka no adan a iweywawalam tiakahiwan kazakazash numa faqlhu a saran Cultural Diversity when Old Merges with New Novel Path to Cultural Awareness In recent years, there has been a great increase in indigenous isa Taiwaan mawalhnak a pruq manasha sa palhkakrikriw, peoples using creative and novel means to demonstrate numa sa parhaway shiminatantu malhkakrikriw, numa ya our traditional culture, as a result of cultural diversity. Take thuini a tiakahiwan a kazakazash ya mriqaz, mawalhnak a traditional totems as an example. Totemic symbols have, for pruq mathuaw maqarman tu shisasaz. hundreds of years, signified sacredness, collective ideology, and sense of identity. As we move into a new economic era, mawalhnak a pruq thau maqa mathuaw a numanuma, new meaning has been given to those totems. They are to demonstrate the uniqueness of each individual. I personally lhmazawaniza mafazaq ananak wa Thau, inangqtu think this is a good sign because it moves culture forwards. ananak uka sa aniamin numa. Ihai a munsai min’ananak a kazakazas masbut. kataunan a pruq mat mawalhnak a pruq, However, before starting to create, we need to have thorough lhmazawaniza kmilhim tiakahiwan kazakazash. mathuaw and precise understanding of our own culture. The young tmara a mafazaq ananak a, mamzai ananak ani inangqtu indigenous people living in urban areas want to learn more mafazaq, antu ukaiza sa Thau inangqtu painan. -

Genetic Diversity of Balanophora Fungosa and Its Conservation in Taiwan

Botanical Studies (2010) 51: 217-222. GENETIC DIVERSITY Genetic diversity of Balanophora fungosa and its conservation in Taiwan Shu-ChuanHSIAO*,Wei-TingHUANG,andMaw-SunLIN Department of Life Sciences, National Chung-Hsing University, 250 Kuo-Kuang Road, Taichung 40227, Taiwan (ReceivedOctober11,2007;AcceptedFebruary26,2010) ABSTRACT. Balanophora fungosa is a rare holoparasitic flowering plant in Taiwan, where it is restricted totheHengchunPeninsulainsouthernmostTaiwan,andOrchidIsland(LanyuinChinese),asmallvolcanic islandoffthesoutheasterncoastofTaiwan.Plantsfromthesetwoareasappearintwodifferentgroups basedonthecoloroftheinflorescence,i.e.,thoseofHengchunareyellow,buttheyarepinkishorangeto redonOrchidI.Thisstudyusedaninter-simplesequencerepeat(ISSR)molecularmarkerapproachandthe unweightedpairgroupmethodwitharithmeticmean(UPGMA)analysistoevaluategeneticvariationsamong populationsof B. fungosa.Theresultsshowedthatthetwogeographicalgroupsrepresentthesamespecies as indicated by a high Dice similarity value of 0.78. Populations from the two areas formed two well-defined clusters,asdidpopulationswithineacharea.Theresultsoftheanalysisofmolecularvariance(AMOVA) showedthatthecomponentsofvariationbetweengroups(31.35%),amongpopulationswithingroups (13.74%),andwithinpopulations(54.91%)weresignificant(p<0.001),indicatingthatvariationsamong individualswithinpopulationscontributedmosttothetotalgeneticvariance.Thepopulationsofthetwoareas werealsodifferentiatedwithgeneticdistancesrangingfrom0.44~0.53forpairedcomparisons.Therefore, werecommendthatprotectedareasbesetasideinbothareasfor -

Checklist of Reptiles in Hong Kong © Programme of Ecology & Biodiversity, HKU (Last Update: 10 September 2012)

Checklist of Reptiles in Hong Kong © Programme of Ecology & Biodiversity, HKU (Last Update: 10 September 2012) Scientific name Common name Chinese Name Status Ades & Kendrick (2004) Karsen et al. (1998) Uetz et al. Testudines Platysternidae Platysternon megacephalum Big-headed Terrapin 大頭龜 Native Cheloniidae Caretta caretta Loggerhead Turtle 蠵龜 Uncertain Not included Not included Chelonia mydas Green Turtle 緣海龜 Native Eretmochelys imbricata Hawksbill Turtle 玳瑁 Uncertain Not included Not included Lepidochelys olivacea Pacific Ridley Turtle 麗龜 Native Dermochelyidae Dermochelys coriacea Leatherback Turtle 稜皮龜 Native Geoemydidae Cuora amboinensis Malayan Box Turtle 馬來閉殼龜 Introduced Not included Not included Cuora flavomarginata Yellow-lined Box Terrapin 黃緣閉殼龜 Uncertain Cistoclemmys flavomarginata Cuora trifasciata Three-banded Box Terrapin 三線閉殼龜 Native Mauremys mutica Chinese Pond Turtle 黃喉水龜 Uncertain Mauremys reevesii Reeves' Terrapin 烏龜 Native Chinemys reevesii Chinemys reevesii Ocadia sinensis Chinese Striped Turtle 中華花龜 Uncertain Sacalia bealei Beale's Terrapin 眼斑水龜 Native Trachemys scripta elegans Red-eared Slider 巴西龜 / 紅耳龜 Introduced Trionychidae Palea steindachneri Wattle-necked Soft-shelled Turtle 山瑞鱉 Uncertain Pelodiscus sinensis Chinese Soft-shelled Turtle 中華鱉 / 水魚 Native Squamata - Serpentes Colubridae Achalinus rufescens Rufous Burrowing Snake 棕脊蛇 Native Achalinus refescens (typo) Ahaetulla prasina Jade Vine Snake 綠瘦蛇 Uncertain Amphiesma atemporale Mountain Keelback 無顳鱗游蛇 Native -

Notes on Some Dietary Items of Eutropis Longicaudata

Herpetology Notes, volume 5: 453-456 (2012) (published online on 7 October 2012) Notes on some dietary items of Eutropis longicaudata (Hallowell, 1857), Japalura polygonata xanthostoma Ota, 1991, Plestiodon elegans (Boulenger, 1887), and Sphenomorphus indicus (Gray, 1853) from Taiwan Gerrut Norval 1,*, Shao-Chang Huang 2, Jean-Jay Mao 3, and Stephen R. Goldberg 4 An understanding of the natural history and ecology of length (SVL) and tail length (TL) were measured to the reptile and amphibian species is essential for successful nearest mm with a transparent plastic ruler; and the tail conservation and management programs (Bury, 2006). A was scored as complete or broken. The E. longicaudata crucial part of the natural history of an animal is its diet, were weighed (body mass) to the nearest 0.1g with a because not only does it reveal the source of the animal’s digital scale, but since the specimens from northern energy for growth, maintenance, and/or reproduction Taiwan were partially dissected and not intact, their (Dunham, Grant and Overall, 1989; Zug et al., 2001), it body masses were not recorded. All the lizards were also indicates part of the ecological roles of the animal. dissected by making a mid-ventral incision, and the Since there may be temporal and spatial variations stomach was removed and slit longitudinally, after in the diet of a species (e.g. Lahti and Beck, 2008; which the stomach content was removed. The stomach Rodríguez et al., 2008; Goodyear and Pianka, 2011), contents were spread in a petri dish and examined under there is a need for dietary descriptions from different a dissection microscope, and all the prey items were localities. -

The Ecology of Lizard Reproductive Output

Global Ecology and Biogeography, (Global Ecol. Biogeogr.) (2011) ••, ••–•• RESEARCH The ecology of lizard reproductive PAPER outputgeb_700 1..11 Shai Meiri1*, James H. Brown2 and Richard M. Sibly3 1Department of Zoology, Tel Aviv University, ABSTRACT 69978 Tel Aviv, Israel, 2Department of Biology, Aim We provide a new quantitative analysis of lizard reproductive ecology. Com- University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA and Santa Fe Institute, 1399 Hyde parative studies of lizard reproduction to date have usually considered life-history Park Road, Santa Fe, NM 87501, USA, 3School components separately. Instead, we examine the rate of production (productivity of Biological Sciences, University of Reading, hereafter) calculated as the total mass of offspring produced in a year. We test ReadingRG6 6AS, UK whether productivity is influenced by proxies of adult mortality rates such as insularity and fossorial habits, by measures of temperature such as environmental and body temperatures, mode of reproduction and activity times, and by environ- mental productivity and diet. We further examine whether low productivity is linked to high extinction risk. Location World-wide. Methods We assembled a database containing 551 lizard species, their phyloge- netic relationships and multiple life history and ecological variables from the lit- erature. We use phylogenetically informed statistical models to estimate the factors related to lizard productivity. Results Some, but not all, predictions of metabolic and life-history theories are supported. When analysed separately, clutch size, relative clutch mass and brood frequency are poorly correlated with body mass, but their product – productivity – is well correlated with mass. The allometry of productivity scales similarly to metabolic rate, suggesting that a constant fraction of assimilated energy is allocated to production irrespective of body size. -

Rethinking Indigenous People's Drinking Practices in Taiwan

Durham E-Theses Passage to Rights: Rethinking Indigenous People's Drinking Practices in Taiwan WU, YI-CHENG How to cite: WU, YI-CHENG (2021) Passage to Rights: Rethinking Indigenous People's Drinking Practices in Taiwan , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13958/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Passage to Rights: Rethinking Indigenous People’s Drinking Practices in Taiwan Yi-Cheng Wu Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Social Sciences and Health Department of Anthropology Durham University Abstract This thesis aims to explicate the meaning of indigenous people’s drinking practices and their relation to indigenous people’s contemporary living situations in settler-colonial Taiwan. ‘Problematic’ alcohol use has been co-opted into the diagnostic categories of mental disorders; meanwhile, the perception that indigenous people have a high prevalence of drinking nowadays means that government agencies continue to make efforts to reduce such ‘problems’. -

Download:Introduction of YUAN CHU

Introduction There are many ethnic groups living on the beautiful island of Taiwan. Among them are 430,000 indigenous status persons, which is about 1.9% of the total population. Although the number is relatively small, they perform superbly well in music, culture, and sports endeavors. The name "YUAN CHU MIN" in fact is a collective term. It includes Atayal, Saisiyat, Bunun, Tsou, Rukai, Paiwan, Puyuma, Amis, Yami, Thao, Kavalan, Truku and Sakizaya, to make up the thirteen indigenous tribes of Taiwan. Austronesia Language Family and Taiwan Indigenous Peoples Since the Paleolithic Age, the earliest inhabitants in Taiwan were the Austronesians. Academic research found that there were once more than 20 aboriginal tribes living in Taiwan and all belonged to the Austronesian family. Some scholars even concluded that Taiwan might be one of the original homelands of the Austronesians. Currently, twelve of the Austroneisan peoples are recognized by the government. They are Atayal, Saisiyat, Bunun, Tsou, Rukai, Paiwan, Puyuma, Amis, Yami, Thao, Kavalan, Truku and Sakizaya. Amis The area of Amis distribution stretches along plains around Mt. Chi-lai in NorthThe area of Amis distribution stretches along plains around Mt. Chi-lai in North Hualien, the long and narrow seacoast plains and the hilly lands in Taitung, Pintung and Hengtsuen Peninsula. At present, the population is about 158,000. The traditional social organization is based mainly on the matrilineal clans. After getting married, the male must move into the female’s residence. Family affairs including finance of the family are decided by the female householder. The affairs of marriage or the allocation of wealth should be Amis Distribution decided in a meeting hosted by the uncles of the female householder.