Reproduction and Aging in Marmosets and Tamarins Suzette D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marmoset (Callithrix Jacchus)

THE USE OF TRANSABDOMINAL PALPATION TO DETERMINE THE COURSE OF PREGNANCY IN THE MARMOSET (CALLITHRIX JACCHUS) I. R. PHILLIPS and SUE M. GRIST Royal College of Surgeons of England, Research Establishment, Downe, Orpington, Kent (Received 2nd September 1974) Summary. Transabdominal palpation was used to determine maturity, course of pregnancy and post-partum changes in marmosets throughout seventy-four full-term pregnancies. The accuracy of the technique is compared with that ofother methods ofstudying the course ofpregnancy in this species. INTRODUCTION Several workers have reported the use of the marmosets (F. Callithricidae) in biomedicai research (Levy & Artecona, 1964; Hampton, Hampton & Land¬ wehr, 1966; Deinhardt, Devine, Passovoy, Pohlman & Deinhardt, 1967; Gengozian, 1969; Epple, 1970; Poswillo, Hamilton & Sopher, 1972). The mem¬ bers of this family are unusual in that they exhibit neither the menstrual cycle of other primates, nor the obvious oestrous cycle of other mammals. Preslock, Hampton & Hampton (1973) demonstrated a mean reproductive cycle of 15-5+1-5 days in Saguinus oedipus. Hearn & Lunn (1975) determined a mean cycle of 16-4+1 -7 days for Callithrix jacchus. The exact day during the reproduc¬ tive cycle on which ovulation occurs has not been determined. Under optimum conditions of husbandry and nutrition, marmosets are ex¬ ceptionally prolific breeders with no sign of a breeding season in captivity (Grist, 1975; Phillips, 1975). They are best maintained as monogamous pairs for breed¬ ing purposes. Although the female marmoset has a simplex uterus, the vast majority of conceptions result in twins, with occasional triplets or singletons. The literature relating to the precise duration of pregnancy in C. -

Controlled Animals

Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Policy Division Controlled Animals Wildlife Regulation, Schedule 5, Part 1-4: Controlled Animals Subject to the Wildlife Act, a person must not be in possession of a wildlife or controlled animal unless authorized by a permit to do so, the animal was lawfully acquired, was lawfully exported from a jurisdiction outside of Alberta and was lawfully imported into Alberta. NOTES: 1 Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column. 2 Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule. 3 This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal. Part 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 1. AMERICAN OPOSSUMS (Family Didelphidae) Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana 2. SHREWS (Family Soricidae) Long-tailed Shrews Genus Sorex Arboreal Brown-toothed Shrew Episoriculus macrurus North American Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Old World Water Shrews Genus Neomys Ussuri White-toothed Shrew Crocidura lasiura Greater White-toothed Shrew Crocidura russula Siberian Shrew Crocidura sibirica Piebald Shrew Diplomesodon pulchellum 3. -

The Use of Degraded and Shade Cocoa Forests by Endangered Golden-Headed Lion Tamarins Leontopithecus Chrysomelas

Oryx Vol 38 No 1 January 2004 The use of degraded and shade cocoa forests by Endangered golden-headed lion tamarins Leontopithecus chrysomelas Becky E. Raboy, Mary C. Christman and James M. Dietz Abstract Determining habitat requirements for threat- consistent across groups. In contrast, all groups preferred ened primates is critical to implementing conservation to sleep in mature or cabruca forest. Golden-headed lion strategies, and plans incorporating metapopulation str- tamarins spent a greater proportion of time foraging and ucture require understanding the potential of available eating fruits, flowers and nectar in cabruca than in habitats to serve as corridors. We examined how three mature or secondary forests. Although the extent to groups of golden-headed lion tamarins Leontopithecus which secondary and cabruca forests can completely chrysomelas in Southern Bahia, Brazil, used mature, sustain breeding groups is unresolved, we conclude that swamp, secondary and shade cocoa (cabruca) forests. both habitats would make suitable corridors for the Unlike callitrichids that show affinities for degraded movement of tamarins between forest fragments, and forest, Leontopithecus species are presumed to depend on that the large trees remaining in cabruca are important primary or mature forests for sleeping sites in tree holes sources of food and sleeping sites. We suggest that and epiphytic bromeliads for animal prey. In this study management plans for golden-headed lion tamarins we quantified resource availability within each habitat, should focus on protecting areas that include access to compared the proportion of time spent in each habitat tall forest, either as mature or cabruca, for the long-term to that based on availability, investigated preferences conservation of the species. -

Range Extension of the Vulnerable Dwarf Marmoset, Callibella Humilis (Roosmalen Et Al

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256101683 Range extension of the vulnerable dwarf marmoset, Callibella humilis (Roosmalen et al. 1998), and first analysis of its long call structure Article in Primates · August 2013 DOI: 10.1007/s10329-013-0381-3 · Source: PubMed CITATIONS READS 5 154 3 authors, including: Guilherme Siniciato Terra Garbino Federal University of Minas Gerais 44 PUBLICATIONS 208 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Escalas de Distribuição de Morcegos Amazônicos View project Revisões filogenia e taxonomia de morcegos neotropicais View project All content following this page was uploaded by Guilherme Siniciato Terra Garbino on 05 February 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Primates (2013) 54:331–334 DOI 10.1007/s10329-013-0381-3 NEWS AND PERSPECTIVES Range extension of the vulnerable dwarf marmoset, Callibella humilis (Roosmalen et al. 1998), and first analysis of its long call structure G. S. T. Garbino • F. E. Silva • B. J. W. Davis Received: 4 April 2013 / Accepted: 2 August 2013 / Published online: 22 August 2013 Ó Japan Monkey Centre and Springer Japan 2013 Abstract We present two new records for the vulnerable Introduction dwarf marmoset, Callibella humilis. The first record, based on observed and photographed individuals, is from a The dwarf marmoset Callibella humilis is currently known campinarana area on the left (west) bank of the Rio Ma- from 12 localities in the lower reaches of the Madeira— deirinha, a left (west)-bank tributary of the Rio Roosevelt Aripuana˜ interfluvium of the southwestern-central Brazil- in the state of Amazonas, municipality of Novo Aripuana˜ ian Amazonia (Roosmalen and Roosmalen 2003). -

Goeldi's Monkey

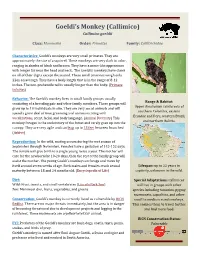

Goeldi’s Monkey (Callimico) Callimico goeldii Class: Mammalia Order: Primates Family: Callitrichidae Characteristics: Goeldi’s monkeys are very small primates. They are approximately the size of a squirrel. These monkeys are very dark in color, ranging in shades of black and brown. They have a mane-like appearance with longer fur near the head and neck. The Goeldi’s monkeys have claws on all of their digits except the second. These small primates weigh only 22oz on average. They have a body length that is in the range of 8-12 inches. The non-prehensile tail is usually longer than the body. (Primate Info Net) Behavior: The Goeldi’s monkey lives in small family groups usually consisting of a breeding pair and other family members. These groups will Range & Habitat: Upper Amazonian rainforests of grow up to 10 individuals in size. They are very social animals and will southern Colombia, eastern spend a great deal of time grooming and communicating with Ecuador and Peru, western Brazil, vocalizations, scent, facial, and body language. (Animal Diversity) This and northern Bolivia. monkey forages in the understory of the forest and rarely goes up into the canopy. They are very agile and can leap up to 13 feet between branches! (Arkive) Reproduction: In the wild, mating occurs during the wet season of September through November. Females have a gestation of 145-152 days. The female will give birth to a single young twice a year. The mother will care for the newborn for 10-20 days, then the rest of the family group will assist the mother. -

Characteristics of Geoffroyâ•Žs Tamarin (Saguinus Geoffroyi

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2015 Characteristics of Geoffroy’s tamarin (Saguinus geoffroyi) population, demographics, and territory sizes in urban park habitat (Parque Natural Metropolitano, Panama City, Panama) Caitlin McNaughton Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, and the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation McNaughton, Caitlin, "Characteristics of Geoffroy’s tamarin (Saguinus geoffroyi) population, demographics, and territory sizes in urban park habitat (Parque Natural Metropolitano, Panama City, Panama)" (2015). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2276. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2276 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Characteristics of Geoffroy’s tamarin (Saguinus geoffroyi) population, demographics, and territory sizes in urban park habitat (Parque Natural Metropolitano, Panama City, Panama) Caitlin McNaughton Ohio Wesleyan University School for International Training: Panamá Fall 2015 Abstract Metropolitan parks are an important refuge for wildlife in developed areas. In the tropics, land conversion threatens rainforest habitat that holds some of the highest levels of biodiversity in the world. This study aims to investigate the characteristics of Geoffroy’s tamarin (Saguinus geoffroyi) population, demographics, and territory size in a highly urbanized forest habitat (Parque Natural Metropolitano (PNM), Panama City, Republic of Panamá). -

Callithrix Kuhli) During the 80 Days from the Initial Day of Pairing

American Journal of Primatology 36185-200 (1995) Development of Heterosexual Relationships in Wied’s Black Tufted-Ear Marmosets (Callithrix kuhh] COLLEEN M. SCHAFFNER’, REBECCA E. SHEPHERD’, CRISTINA V. SANTOS’.’, AND JEFFREY A. FRENCH’ ‘Callitrichid Research Facility, Department of Psychology, University of Nebraska at Omaha;‘Departmento Psicologia Exoerimental, Universidade de Sdo Paulo, Sdo Paulo, Brazil In tamarins and marmosets, long-term stable sociosexual relationships are formed between heterosexual adults, but these “monogamous” rela- tionships are often formed in groups that contain multiple adults of both sexes. The patterning of interactions during pair formation may therefore be shaped by this demographic profile. We evaluated the development of sociosexual relationships in six captive pairs of Wied’s black tufted-ear marmosets (Callithrix kuhli) during the 80 days from the initial day of pairing. Social behavior, sexual behavior and activity profiles were re- corded. Social behaviors, including allogrooming, grooming solicitation, and intragroup monitoring calls, increased across the four 20-day time blocks. Males were more responsible than females for maintaining intra- pair proximity during the first 40 days of pairing. Females and males were equally responsible for intrapair proximity maintenance after this time. The highest rates of sexual behavior, including copulation and proceptive open mouth displays, occurred upon pairing and then decreased non-sig- nificantly over time. The results indicate that sexual relationships in cal- litrichid primates are not dependent on the prior existence of a social relationship between males and females. Higher rates of copulation, greater male responsibility for proximity maintenance, and male initia- tive in sexual interactions early in pairing are consistent with a male reproductive strategy in which male-male competition may be common. -

Foraging Behavior and Microhabitats Used by Black Lion Tamarins, Leontopithecus Chrysopyqus (Mikan) (Primates, Callitrichidae)

Foraging behavior and microhabitats used by black lion tamarins, Leontopithecus chrysopyqus (Mikan) (Primates, Callitrichidae) Fernando de Camargo Passos 2 Alexine Keuroghlian 3 ABSTRACT. Foraging in the Black Lion Tamarin (L. chrysopygus Mikan, 1823) was observed in the Caetetus Ecological Station, São Paulo, southeastern Brazil, during 83 days between November 1988 to October 1990. These tamarins use manipuJative, specitic-site foraging behavior. When searching for animal prey items, they examine a variety ofmicrohabitats (dry palm leaves, twigs, under loose bark, in tree cavities). These microhabitats were spatially dispersed among different forest macrohabitats such as swamp torests and dry forested areas. These data indicated that the prey foraging behavior of L. chrysopygus was quite variable, and they used a wide variety ofmicrohabitats, different ofthe other lion tall1arin species. KEY WORDS. Callitrichidae, Leontopithecus chrysopygus, black lion tamarin, ani mai prey, foraging behavior, diet, microhabitats Lion tamarins, Leontopithecus Lesson, 1840, are considered primarily in sectivores and frugivores (COIMBRA-FILHO & MITTERMEIER 1973), or omnivores (KLElMAN et aI. 1988) because of the diversity of their diet. ln the wild, they consume mostly fruits, exudates, nectar, and animal prey. ln comparison to fruits, animal prey make up a relatively small proportion ofthe diet and are costly to obtain, but its nutritional vai ue make it an essential component of their diet. The prey of black lion tamarins (L. chrysopygus) may include a variety ofinvertebrates (insects, spiders, and other arthropods) and small vertebrates, such as anuran frogs (CARVA LHO et aI. 1989; PASSOS 1999). ln this note, we present our observations on prey foraging. We then compare them with studies of other lion tamarin species and discuss some of the unique aspects ofblack lion tamarin foraging in re\ation to the microhabitats they use. -

Brazil North-Eastern Mega Birding Tour 21St September to 12Th October 2017 (22 Days) Trip Report

Brazil North-eastern Mega Birding Tour 21st September to 12th October 2017 (22 Days) Trip Report Grey-breasted Parakeet by Colin Valentine Trip Report Compiled by Tour Leader, Keith Valentine Rockjumper Birding Tours | Brazil www.rockjumperbirding.com Trip Report – RBL Brazil - North-eastern Mega 2017 2 Simply put, our recently-completed tour of NE Brazil was phenomenal! Our success rate with the region’s most wanted birds was particularly good, and we also amassed an exceptional 103 endemics in the process, which few tours have ever been able to replicate in the past. This was all achieved in just 22 days, which gives an excellent indication of just how good our itinerary is. There are few other tours on the planet that offer the number of threatened, endangered and critically endangered species as NE Brazil. We were sublimely successful in our quest for these, as we enjoyed magnificent encounters with Araripe Manakin, Lear’s Macaw, Grey-breasted, White-eared, Golden-capped and Ochre- marked Parakeets, White-collared Kite, Pink-legged Graveteiro, Hooded Visorbearer, Banded and White-winged Cotingas, White- browed Guan, Red-browed Amazon, Alagoas, Orange-bellied, Pectoral, Sincora, Bahia, Band-tailed and Narrow-billed Antwrens, Slender, Rio de Janeiro and Scalloped Antbirds, Seven-colored Tanager, Minas Gerais, Alagoas and Bahia Tyrannulets, Buff- breasted and Fork-tailed Tody-Tyrants, Bahia Spinetail, Fringe- backed Fire-eye, Hook-billed Hermit, Striated Softtail, Plumbeous Antvireo, White-browed Antpitta, Black-headed Berryeater, Wied’s Tyrant-Manakin, Diamantina Tapaculo, Buff-throated Purpletuft, Black-headed Berryeater by Serra Finch and many others. Colin Valentine Our 22-day adventure began with a short drive east of Fortaleza to the coastal region of Icapui, where our target birds – Little Wood and Mangrove Rails – gave themselves up easily and provided saturation views. -

The Common Marmoset in Captivity and Biomedical Research 477 Copyright © 2019 Elsevier Inc

CHAPTER 26 The Marmoset as a Model in Behavioral Neuroscience and Psychiatric Research Jeffrey A. French Neuroscience Program and Callitrichid Research Center, University of Nebraska at Omaha, NE, United States INTRODUCTION top-down as well as bottom-up regulation of affect and emotion. Finally, the changes in NHP brain struc- In its mission statement, the US National Institutes of ture and function can facilitate the mediation of chal- Health provides a clear statement of its focus: “. to seek lenges associated with group living, including fundamental knowledge about the nature and behavior aggression, affiliation, and the establishment and main- of living systems and the application of that knowledge tenance of long-term complex social relationships that to enhance health, lengthen life, and reduce illness and distinguish these species from nonprimate animals [5]. disability” [emphasis added, www.nih.gov/about-nih/ what-we-do/mission-goals, 2015). Disorders associated with brain or behavioral dysfunction represent the lead- The Utility of Marmosets in Behavioral Models ing disease burden and highest source of lifetime years in Neuroscience and Psychiatric Research living with disability on a global basis (YLD: [1]) and together these disorders represent one of the leading From the perspective of a biomedically oriented contributors to disease-associated mortality worldwide focus, research on behavioral states (both normative [2]. Clearly, then, there is a premium on understanding and atypical) is of interest to the extent that it can pro- both normative behavioral states and their relationship vide useful information regarding the developmental to brain function and the nature of brain dysfunction factors that lead to normative neuropsychological func- as is relates to pathological behavioral states. -

Cotton-Top Tamarin Neotropical Region

Neotropical Region Cotton-top Tamarin Saguinus oedipus (Linnaeus, 1758) Colombia (2008) Anne Savage, Luis Soto, Iader Lamilla & Rosamira Guillen Cotton-top tamarins are Critically Endangered and found only in northwestern Colombia. They have an extremely limited distribution, occurring in northwestern Colombia between the Río Atrato and the lower Río Cauca (west of the Río Cauca and the Isla de Mompos) and Rio Magdalena, in the departments of Atlántico, Sucre, Córdoba, western Bolívar, northwestern Antioquia (from the Uraba region, west of the Río Cauca), and northeastern Chocó east of the Río Atrato, from sea level up to 1,500 m (Hernández- Camacho and Cooper 1976; Hershkovitz 1977; Mast et al. 1993). The southwestern boundary of the cotton- top’s range has not been clearly identified. Mast et al. (1993) suggested that it may extend to Villa Arteaga on the Río Sucio (Hershkovitz 1977), which included reports of cotton-top tamarins in Los Katios National Park. Barbosa et al. (1988), however, were unable to find any evidence of cotton-top tamarins in this area or in Los Katios, where they saw only Saguinus geoffroyi. Groups have been seen in the Islas del Rosario and Tayrona National Park in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (Mast et al. 1993; A. Savage and L. H. Giraldo pers. obs.). However, these populations were founded by captive animals that were released into the area (Mast et al. 1993), and we believe to be outside the and their long-term survival, buffering agricultural historic range of the species. zones, is constantly threatened. Colombia is among the top ten countries suffering The extraction and exploitation of natural deforestation, losing more than 4,000 km2 annually resources is constant in Colombia’s Pacific coastal (Myers 1989; Mast et al. -

Behavioral and Ecological Interactions Between Reintroduced Golden

99 Vol. 49, n. 1 : pp. 99-109, January 2006 ISSN 1516-8913 Printed in Brazil BRAZILIAN ARCHIVES OF BIOLOGY AND TECHNOLOGY AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL Behavioral and Ecological Interactions between Reintroduced Golden Lion Tamarins ( Leontopithecus rosalia Linnaeus, 1766) and Introduced Marmosets ( Callithrix spp, Linnaeus, 1758) in Brazil’s Atlantic Coast Forest Fragments Carlos Ramon Ruiz-Miranda 1,2*, Adriana Gomes Affonso 1, Marcio Marcelo de Morais 1,2 , Carlos Eduardo Verona 1, Andreia Martins 2 and Benjamin Beck 3 1Laboratório de Ciências Ambientais; Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense; Av. Alberto Lamego, 2000; Horto; 28013-600; Campos dos Goytacazes - RJ - Brasil. 2Associação Mico Leão Dourado; C. P. 109968; 28860- 970; Casimiro de Abreu - RJ - Brasil. 3Department of Conservation Biology; National Zoological Park; Smithsonian Institution; 20008; Washington, DC - EUA ABSTRACT Marmosets (Callithrix spp.) have been introduced widely in areas within Rio de Janeiro state assigned for the reintroduction of the endangered golden lion tamarin (Leontopithecus rosalia ). The objetives of this study were to estimate the marmoset (CM) population in two fragments with reintroduced golden lion tamarin to quantify the association and characterize the interactions between species. The CM population density (0,09 ind/ha) was higher than that of the golden lion tamarin (0,06 ind/ha). The mean association index between tamarins and marmosets varied among groups and seasons (winter=62% and summer=35%). During the winter, competition resulted in increases in territorial and foraging behavior when associated with marmosets. Evidence of benefits during the summer was reduced adult vigilance while associated to marmosets. Golden lion tamarins were also observed feeding on gums obtained from tree gouges made by the marmosets.