Portable Skills Handout #1

Con d uct i ng a Cost‐Ben e fit A n a ly s is

Do you have difficulty making purchasing decisions? Have you ever wished you could figure out how to decide more easily?

Some decisions, such as purchasing decisions, investment decisions, and others, can be solved using a mathematical model known as “Cost Benefit Analysis.” Cost‐benefit analysis is a process that compares the costs associated with a decision, and the benefits or savings that the choice provides. In business, cost‐benefit is performed to help make decisions such as those to upgrade machinery or build a factory.

Steps in Performing a Cost‐Benefit Analysis. In its simple form, cost‐benefit analysis is conducted using the following steps:

1) Determine the costs of the decision. Costs are the tangible or intangible resources (cash expenditures, labor, time and machinery) associated with a decision option. Costs can be either a one‐time expenditure, or they may be recurring or ongoing. 2) Calculate the benefits that the decision will provide. Benefits are the gains that the decision‐ maker stands to receive as a result of selecting a particular decision option. 3) Figure out the level of benefits needed to recoup all the costs of the investment. What does the decision have to produce to pay for itself? This is known as the break even point. 4) Subtract the ‘costs’ from the ‘benefits’. Is the result positive? Then the decision you are considering is likely to be economically desirable. If it is negative, it is not economically desirable. 5) Work out the time it will take for the benefits to repay the costs. This is known as the payback period.

After working through these steps for each choice, determine which option best fits your goals. Are you trying to save money? Which option is least expensive, or which offers the most cost savings? Or are you looking to make an investment? In that case, which option offers the best return?

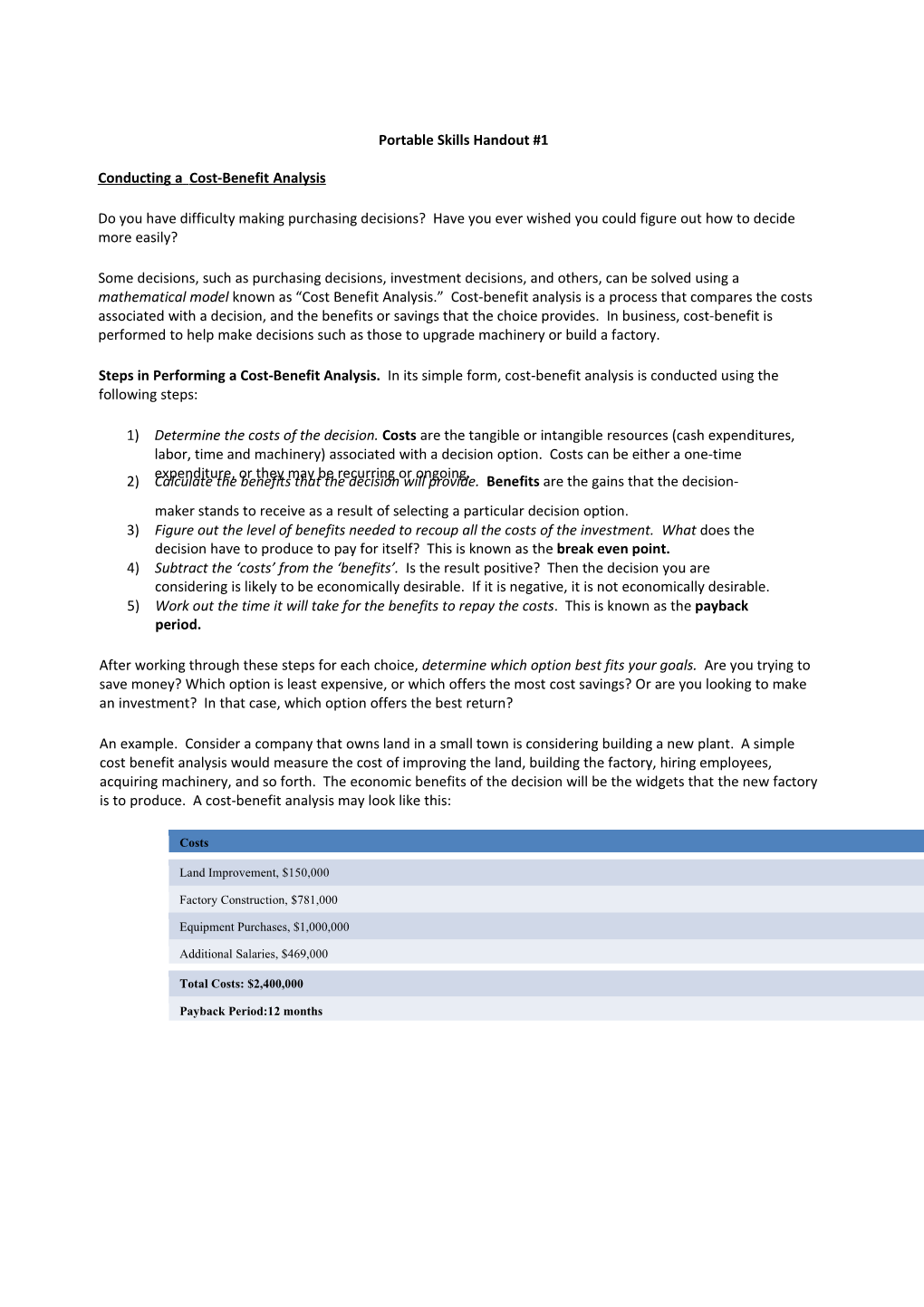

An example. Consider a company that owns land in a small town is considering building a new plant. A simple cost benefit analysis would measure the cost of improving the land, building the factory, hiring employees, acquiring machinery, and so forth. The economic benefits of the decision will be the widgets that the new factory is to produce. A cost‐benefit analysis may look like this:

Costs

Land Improvement, $150,000

Factory Construction, $781,000

Equipment Purchases, $1,000,000

Additional Salaries, $469,000

Total Costs: $2,400,000

Payback Period:12 months The Li m its of Cost B e nefit Analysis

Decisions can be complicated in many ways ‐ especially when we aren’t aware of all the costs and impacts associated with our options.

When making decisions based on cost‐benefit analysis, it is helpful to be aware of its shortcomings. These include:

1) The problem of measurement. The big problem with assigning financial values to costs and benefits is that sometimes these are hard to measure. For example, consider ‘intangible’ costs, like the impact that a widget factory located behind an elementary school may have on the school and its students. How are these costs quantified?

2) Subjectivity. Many times, cost‐benefit analysis may call for estimates, value judgments, and other subjective measurements that vary from party to party. This complicates efforts to quantify costs and benefits.

3) Direct vs. Indirect Costs and Benefits. Most often, decision‐makers using cost benefit analysis consider only the direct costs of their purchasing or investment decision. Likewise, the costs and benefits to parties besides the decision‐maker are often ignored.

The Ethical Objections. Some people object on ethical grounds to the application of cost‐benefit analysis when making some kinds of decisions – particularly those involving healthcare and the environment. Turning back to the previous module’s ‘ethical principles’, we can start to understand why,

1) The Utilitarian Objection. Do you remember the utilitarian rule from the last module? It states that the best decisions bring about the greatest possible benefit for the greatest number of people affected by the decision. Cost‐benefit analysis only considers the harms and benefits of only the decision‐maker. 2) The Practical Objection. Also, the ‘practical’ rule’ states people making ‘right’ decisions, or behaving properly “should be comfortable if their actions or behavior guided all future action, or became some sort of universal law”. Would you be comfortable putting a dollar value on the health of the environment?

Despite its shortcomings, however, cost‐benefit analysis is a powerful tool that decision‐makers can use in a variety of different scenarios. Portable Skills Handout #3

Who is Af f ected by Business Decisi o n s : Stakeholder Theory

Businesses are formed in order to pursue shared economic goals – most frequently, profits ‐‐ for its owners. But who else is a business responsible to, besides its owners?

Businesses are sometimes described as a ‘chain’, where ‘inputs’ from suppliers are ‘converted’ by employees and machinery into ‘outputs’ it sells to its customers. The organization acts entirely in the economic interest of its owners and facilitates this input‐conversion‐output process. This is known as the traditional ‘shareholder’ model of the corporation, where the input, conversion, and output process is the only responsibility of the corporation – and all parties involved answering to the business’s owners or shareholders.

But these aren’t the only groups affected by business decisions. Consider, for example, the communities where a business operates. What happens when a company chooses to relocate? Who is affected by that decision? What happens to the area shops and stores when an area manufacturer relocates, and its employees no longer shop there?

The Stakeholder Model

There are many parties affected by a business’s actions – not just the owners, or ‘shareholders’. These other interested parties, or stakeholders, include owners and management, employees, suppliers, and customers – and also, communities, governments, prospective employees, prospective customers, and the public‐at‐large. In turn, organizations have a responsibility to these stakeholders as well as their owners or shareholders.

According to stakeholder theory, business is responsible for its own actions, and should answer to the numerous parties that either directly or indirectly contribute to its input, conversion and output activities. The number of different ‘stakeholders’ to which an organization has positive duties to consider in its decisions are illustrated in the table below. The Stak e holder M o del

1) Customers. Includes distributors, wholesalers, and end‐users that purchase the organization’s products or services. They trust the organization to deliver safe, quality products and services. 2) Partners. Includes suppliers, vendors and other partners who conduct business with the organization. They depend on it to act with integrity. 3) Employees. Part and full‐time employees, contractors, and even management all provide human capital to the organization, and depend on it for a livelihood in exchange. 4) Owners & Investors. Owners of the organization – and also creditors such as banks and bondholders ‐‐ trust that decisions will result in positive returns on their investments. 5) Communities and Society at large. Communities in which the organization operates depend on the organization as much as the organization depends on them. This includes the people who live where the business operates – and also, the surrounding environment. Business decisions can have profound effects on communities. 6) The State. Federal, state, and local governments and their agencies provide services for the organization (such as fire protection) Portable Skills Handout #4

Playing Hardball: E t hi cs and Negotiations

What is negotiating? New City isn’t the only place that you are likely to want to negotiate. There are many areas in life where negotiating plays a part. You may negotiate where you want to go for your lunch hour. You may negotiate with your friends to decide what television programs to watch or video games to play. Businesses negotiate purchases of materials and sales of their products. The FBI negotiates with terrorists to free hostages. Nations negotiate ‘free trade’ agreements. But you don’t have to be in law enforcement or top‐level diplomacy in order to negotiate. Everyone does it all the time.

We negotiate for several reasons. Some reasons people negotiate are as follow: 1) There needs to be an agreement on how to share or divide a fixed amount of resources such as land, property or time. 2) Something can be created by multiple parties which each can not do on their own. 3) A problem or dispute between two or more parties must be settled.

Even in these circumstances, people may not necessarily negotiate – but that is because they neglected to do so.

Negotiating and ethical behavior. So what do ethics have to do with negotiations? Quite simply, arriving at a clear and precise negotiated agreement depends on the willingness of the parties involved in the negotiation to present accurate information about their position, priorities and preferences. At the same time, however, negotiating parties may be protective of their self‐interests – and so may be motivated to withhold or manipulate information in the negotiating process.

Why do people behave unethically in negotiations? Most unethical behavior within negotiations occurs for one of two reasons: 1) Increased Bargaining Power. By withholding or manipulating information, the unethical negotiator is able to shore up their bar g aining powe r , or their ability to force their negotiating partner into a deal with relatively favorable terms.

2) Self‐serving rationalizations. People who negotiate unethically almost never view themselves as corrupt or immoral. More likely, they feel they are ‘forced’ to behave unethically because of others or because circumstances dictate. They may believe the behavior is unavoidable, harmless, or that it is deserved. Sometimes people lie because they expect that others in the same situation would as well – and so they feel that it is justified. Strategies for Dealing with Deceptive Negotiators. Here are some strategies for dealing with people who you believe are deceiving you in a negotiation:

1) Call the tactic. Indicate that you know the other party to the negotiation is lying or bluffing. Do so firmly, and indicate your displeasure.

2) Discuss what you see and help the party change to more honest behaviors. This is a variation on ‘call the tactic’ where you try to convince the party that honesty, in the long run, will put him in a better position than any form of bluffing or deception.

3) Respond in kind. This tactic is not recommended – simply because it will escalate the destructive behavior, dragging you ‘into the mud’ along with the other party to the negotiation.

4) Ignore the tactic. If you are aware the other party is bluffing or lying, simply ignore it.